Negative income tax

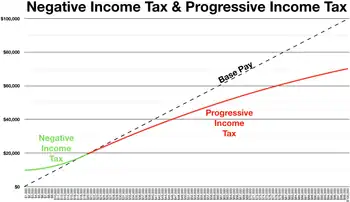

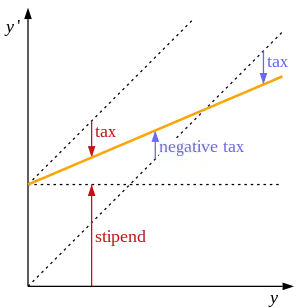

In economics, a negative income tax (NIT) is a system which reverses the direction in which tax is paid for incomes below a certain level; in other words, earners above that level pay money to the state while earners below it receive money, as shown by the blue arrows in the diagram. NIT was proposed by Juliet Rhys-Williams while working on the Beveridge Report in the early 1940s and popularized by Milton Friedman in the 1960s as a system in which the state makes payments to the poor when their income falls below a threshold, while taxing them on income above that threshold. Together with Friedman, supporters of NIT also included James Tobin, Joseph A. Pechman, and Peter M. Mieszkowski, and even then-President Richard Nixon, who suggested implementation of modified NIT in his Family Assistance Plan. After the increase in popularity of NIT, an experiment sponsored by the US government was conducted between 1968 and 1982 on effects of NIT on labour supply, income, and substitution effects.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Taxation |

|---|

|

| An aspect of fiscal policy |

Generic negative income tax

The view that the state should supplement the income of the poor has a long history (see Universal basic income § History). Such payments are seen as benefits if they are limited to those who lack other income, or are conditional on specific needs (such as number of children), but are seen as negative taxes if they continue to be received as a supplement by workers who have income from other sources. The withdrawal of benefits when the recipient ceases to satisfy a firm eligibility criterion is often seen as giving rise to the welfare trap.

The level of support provided to the poor by a negative tax is thought of as parametrically adjustable according to the opposing claims of economic efficiency and distributional justice. Friedman's NIT lacks this adjustability owing to the constraint that other benefits would be largely discontinued; hence a wage subsidy is more representative of generic negative income tax than is Friedman's specific Negative Income Tax.

In 1975 the United States implemented a negative income tax for the working poor through the earned income tax credit. A 1995 survey found that 78% of American economists supported (with or without provisos) the incorporation of a negative income tax into the welfare system.[2]

Theoretical development

Theoretical discussion of negative taxation began with Vilfredo Pareto, who first made a formal distinction between allocative efficiency (i.e. the market's ability to give people what they want subject to their incomes) and distributive justice (i.e. the question of whether these incomes are fair in the first place). He sought to show that market economies allocated resources optimally within the income distributions they give rise to, but accepted that there was nothing optimal about these distributions themselves. He concluded that if society wished to maximise wellbeing, it should let market forces govern production and exchange and then correct the result by 'a second distribution... performed in conformity with the workings of free competition'.[3] His argument was that a direct transfer obtained a given redistributive effect with the least possible reduction of economic efficiency, and was preferable to government interference in the market (as happens in modern economies through the minimum wage) which damages efficiency by introducing distortions.

Abram Bergson and Paul Samuelson (drawing on earlier work by Oscar Lange[4]) gave a more formal statement to Pareto's claims.[5] They showed that the optimum of efficiency associated with market competition fell short of maximum wellbeing as reflected by a social welfare function only through distributional effects, and that a true optimum could be obtained if the state were to transfer income through 'lump sum taxes or bounties', where 'bounties' are negative taxes and 'lump sum' is Samuelson's term for a hypothetical redistribution with no distortionary consequences.

Optimal taxation theory

It follows from the Bergson/Samuelson analysis that any proposed measure (including the proposal to leave things as they are) can be assessed according to the balance it achieves between three factors: (i) the improvement in overall wellbeing from a more equitable distribution; (ii) the loss in economic efficiency due to the distortions introduced; and (iii) the administrative costs. The first of these cannot easily be equated to a sum of money; the last is unlikely to be a dominant factor. Hence redistribution should be pursued up to the point at which any further (non-monetary) benefits from a more equal distribution would be offset by the resulting monetary loss of economic efficiency.

The Bergson/Samuelson theory was developed in a broadly utilitarian framework. A fourth factor could be added in the form of a moral claim derived from present ownership or legitimate earning. Considerable weight was placed on this during the Enlightenment but Hume and the Utilitarians rejected it.[6] It is seldom mentioned nowadays but cannot be dismissed a priori as a relevant consideration.

The theoretical study of the trade-off between equity and efficiency was initiated by James Mirrlees in 1971.[7] Eytan Sheshinski summarised:

In various examples calculated by Mirrlees, the optimal income-tax schedule appears to be approximately linear with a negative tax at low incomes.[8]

Friedman's NIT

"Negative Income Tax" became prominent in the United States as a result of advocacy by Milton and Rose Friedman, who first put forward a concrete proposal in 1962 in a brief section of their book Capitalism and Freedom.[9] Their system is equivalent in its operation to most forms of Universal basic income (UBI) (qv., particularly the section Fundamental Principles for the equivalence).

In the aforementioned work, Friedman provides five benefits of the negative income tax. Firstly, Friedman argues that it provides cash which the individual sees as the best possible way of support. Secondly, it targets poverty directly through income rather than through general old-age benefits or farm programs. Thirdly, negative income tax could in his opinion replace all supporting programs present at that time and provide one universal program. Fourthly, in theory the cost of negative income tax can be lower than the cost of existing programs mainly due to lower administrative costs. Lastly, the program should not distort the market in the way minimum wage laws or tariffs do.[9]

Friedman envisioned the NIT followingly in an interview in 1968: Considering family A of four with income $4000 and Family B of four with income $2000. If the break-even income would be $3000, after filing the tax report, family A would pay the tax on $1000 while family B would be entitled to receive, assuming the 50% NIT rate, $500. Meaning half of the difference between what they earn and the break-even income. Therefore, a family with $0 income would be entitled to receive $1500 in subsidy. Friedman argued NIT would not destroy the incentive to work, as compared to guaranteed income programmes (GIP) with 100% effective marginal tax rate, i.e. with the GIP workers lose $1 of subsidy for each $1 increase in wage.[10]

In his 1966 "View from the Right" paper Milton Friedman remarked that his proposal...

has been greeted with considerable (though far from unanimous) enthusiasm on the left and with considerable (though again far from unanimous) hostility on the right. Yet, in my opinion, the negative income tax is more compatible with the philosophy and aims of the proponents of limited government and maximum individual freedom than with the philosophy and aims of the proponents of the welfare state and greater government control of the economy.[11]

Friedman also elaborated and provided two reasons for the hostility from the right. Firstly, he mentions that the right is frightened due to the introduction of a guaranteed minimum income the poor would have a disincentive to improve their well-being. Secondly, the right is not certain about the political outcomes of the NIT, as there exist threats that there will be an upward pressure on the break-even incomes among politicians.[11]

The Friedmans together promoted the idea to a wider audience in 1980 in their book and television series Free to Choose. It has often been discussed (and endorsed[2]) by economists but never fully implemented. Advantages claimed for it include:

- Alleviating poverty

- Eliminating the "welfare trap"

- Streamlining the benefits system.

The alleviation of poverty was mentioned in Capitalism and Freedom where Friedman argued that in 1961 the US government spent around 33 billion on welfare payments e.g. old age assistance, social security benefit payments, public housing, etc. excluding mainly veterans´ benefits and other allowances. Friedman recalculated the spending between 57 million consumers in 1961 and came to the conclusion that it would have financed 6000 dollars per consumer to the poorest 10% or 3000 dollars to the poorest 20%. Friedman also found out that a program raising incomes of the poorest 20% to the lowest income of the rest would cost the US government less than half of the amount spent in 1961.[9]

The Friedmans' writings were influential for a period with the American political right, and in 1969 President Richard Nixon proposed a Family Assistance Program which had points in common with UBI. Milton Friedman originally supported Nixon's proposal but eventually testified against it on account of its perverse labor incentive effects.[12][13] Friedman was mainly opposed to the idea that Nixon's program would be combined with existing programs at that time, rather than replacing the existing programs as Friedman originally proposed.[1]

Meanwhile, support for negative income tax was increasing among the political left. Paul Samuelson argued in Newsweek that it was an idea whose time had come, and more than 1,200 academic economists signed a petition in support of it. Friedman withheld his signature, possibly on the grounds that the petition didn't explicitly describe the new measure as a replacement rather than a supplement to existing programs.[13]

As civic disorder diminished in the US, support for negative income tax waned among the American right. Instead the doctrine came to be particularly associated with the political left, generally under the name "basic income" or derivatives. It received further impetus in Europe with the founding of the Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN) in 1986. Asked in 2000 how he viewed a basic income "compared to the alternative of a negative income tax", Friedman replied that the measures were not alternatives and that basic income was "simply another way to introduce a negative income tax", giving a numerical example of their equivalence.[12]

Experiments on the effect of NIT on the labour supply

The experiments on NIT have been conducted in the US between years 1968 and 1982 and the expenditures were 225 million recalculated for the 1984 value. The first results have been that the husbands reduced labour supply by about the equivalent of two weeks of full-time employment. On the other hand, Wives and single female heads reduced it by three weeks and the youth reduced the labour supply by four weeks.[14]

Social Policy Experiments on Negative Income:

The New Jersey Income Maintenance Experiment (NJIME)

The New Jersey Income Maintenance Experiment (NJIME) was a negative income tax program conducted between 1968 and 1972. The experiment was designed to test the effectiveness of a negative income tax program in reducing poverty and promoting work incentives.

The experiment involved 1,357 families from three different regions of New Jersey. The families were randomly assigned to one of four groups: a control group, a group that received a flat grant, a group that received a negative income tax based on earnings, and a group that received a negative income tax based on family income.

The experiment tested different guarantee levels and tax rates to determine the optimal parameters for a negative income tax program. The guarantee levels ranged from 0.5 to 1.25 times the poverty line, and the tax rates ranged from 0.3 to 0.7.

The results of the experiment showed that the negative income tax program had a significant impact on reducing poverty rates. The families that received the negative income tax had higher incomes and were less likely to live in poverty than those in the control group. The program also had a positive impact on work incentives, as the families that received the negative income tax were more likely to work than those in the control group.

The optimal parameters for the negative income tax program were found to be a guarantee level of 0.75 times the poverty line and a tax rate of 0.5. These parameters provided the greatest reduction in poverty rates while also promoting work incentives.

Overall, the NJIME provided valuable insights into the potential benefits and challenges of a negative income tax program. It demonstrated that such a program could significantly reduce poverty rates and promote work incentives, but that careful consideration of program parameters is needed to ensure effectiveness and sustainability over the long term.[15]

The Rural Income Maintenance Experiment

The Rural Income Maintenance Experiment was conducted in Iowa and North Carolina between 1969 and 1973. The study involved 809 low-income families in rural areas and aimed to test the effects of different levels of income guarantees and tax rates on work incentives and poverty reduction.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups, which received different levels of guaranteed income and tax rates. The guaranteed income levels ranged from 50% to 100% of the poverty line, and the tax rates ranged from 30% to 70%. The study aimed to examine how changes in these variables affected participants' work behavior and income levels.

The study found that the guaranteed income had a small negative effect on work hours, but this effect was more significant for secondary earners (such as spouses) than primary earners. The study also found that higher guaranteed income levels led to small reductions in poverty rates, but the impact was not statistically significant.

Overall, the Rural Income Maintenance Experiment provided some insights into the effects of income guarantees on work behavior and poverty reduction in rural areas, but the results were mixed and not as clear as those from other social policy experiments such as the Negative Income Tax experiments.[16]

The Seattle-Denver Income Maintenance Experiment (SIME)

The Seattle-Denver Income Maintenance Experiment (SIME) was one of the largest social policy experiments ever conducted in the United States. It was designed to test the effects of different income support programs on poverty reduction and employment rates. The study was conducted between 1971 and 1982 and involved over 8,000 families in Seattle and Denver. Testing guarantee levels were from 0.95 to 1.40

One of the income support programs tested in the SIME was a negative income tax. Under this program, low-income individuals and families received a subsidy from the government rather than paying taxes. The subsidy was calculated based on the individual or family's income, and the subsidy decreased as income increased.

The SIME found that the negative income tax had a positive impact on reducing poverty and increasing employment. The study found that families receiving the subsidy were more likely to work than those who did not receive the subsidy. In addition, the study found that the negative income tax had a positive impact on children's educational outcomes, including higher high school graduation rates and higher levels of educational attainment.

The SIME also tested other income support programs, including a guaranteed income program and a work requirement program. The guaranteed income program provided a fixed income to families regardless of their employment status, while the work requirement program required participants to work or participate in job training programs to receive benefits. The study found that both of these programs had positive effects on poverty reduction and employment rates as well.

In the end, the SIME was an important study that provided valuable insights into the effectiveness of different income support programs. The study showed that a negative income tax can be an effective tool for reducing poverty and increasing employment, but it also demonstrated that other types of income support programs can be effective as well. The findings of the SIME have influenced social policy debates in the United States and around the world, and continue to be relevant today as policymakers consider how to address poverty and inequality.[17]

The Mincome Experiment

The Mincome experiment was a social policy experiment conducted between 1974 and 1979 in the city of Dauphin, Manitoba, Canada. The experiment was designed to test the effectiveness of a guaranteed annual income program and also included a negative income tax component.

Under the negative income tax component, residents whose income fell below a certain threshold would receive a payment from the government to bring their income up to the threshold level. The negative income tax was intended to provide a safety net for low-income individuals and families, and to encourage work by ensuring that there would always be a financial incentive to work, even if the job paid low wages.

The results of the Mincome Experiment were positive. The negative income tax had a significant impact on reducing poverty in the community, with a 30% reduction in poverty rates observed during the study period. The program also had a positive impact on mental health outcomes, with a reduction in hospitalization rates for mental health issues.

The Mincome Experiment was a groundbreaking study that demonstrated the potential benefits of a negative income tax in reducing poverty and improving overall well-being. The study has been cited as evidence in support of negative income tax proposals, and has influenced social policy debates in Canada and around the world.[18]

However, despite the positive results of the Mincome Experiment, the program was never implemented on a large scale due to concerns about its cost and feasibility. Nevertheless, the Mincome Experiment remains an important example of how social policy experiments can provide valuable insights into the effectiveness of different policy approaches, and continues to inform discussions about poverty reduction and income support programs today.

Results of the individual experiments

The individual results were districted into four categories: husbands, wives, single female heads, the youth. Firstly, it was noted that there is an unambiguous decrease in labour supply as a result of NIT and that there exists a pattern among each of the groups. The results show that husbands are the least responsive to NIT in terms of withdrawal from labour force while the youth is the most responsive. Moreover, the percentage responses are from 5-25% equalling 1–5 weeks of full-time work. The employment rate ranges from 1 to 10% .[14] It is however important to note that while on one hand the youth was the most responsive to NIT, on the other hand the decrease in labour supply was equalled by increase in school attendance. Moreover, the chances of completing school education also rose notably in New Jersey by 5% and in Seattle-Denver by 11%.[19]

Considering results from the Seattle-Denver experiment, it can be shown that the two-parent families that received $2,700 decreased their earnings by almost $1,800. Therefore, spending $2,700 on transfers to two-parent families in Seattle-Denver increased their income by only $900. This raised the question whether taxpayers would be willing to pay $3 in order to increase the income of aforementioned families by $1.[20]

Implications to the real world

An attempt was made to synthesise the results and provide a nation-wide estimate of the effects of NIT in the US using two plans, one with 75% and the other with 100% guarantee and 50% and 70% tax rates. The corresponding programmes would cost between 6.7 and 16.3 billion dollars, (-5.3) to 4.5 billion dollars, 55.5 to 61.1 billion dollars and 15.4 to 25.7 billion dollars (value expressed in 1985 dollars) respectively. These are net costs, meaning how much more the NIT would cost relative to the welfare programmes in effect at the time. For the latter two options, i.e. 100% guarantee with either 50% or 70% tax rate, it would represent an increase in spending equal to 1.5 percent of the gross national product (GNP) and 0.4-0.6 percent of GNP. The net increase could be financed by increase in federal taxes from 2 to 4 percent. While the cost of eliminating poverty seemed attainable, the issue of decreased earnings and self-support among families remained prevalent.[20] Hence, the issues likely caused the decrease in interest in implementation of NIT, as the work of donor is a bit higher than the work of the recipient and can potentially lead to free riding which would destroy the entire framework.[21]

Comparison to universal basic income

A negative income tax is structurally similar to a universal basic income, as both are capable of achieving the exact same net transfer of income. However, the two mechanisms may differ in the cost to the government, the timing of tax payments, and the psychological perceptions from taxpayers.[22][23]

NIT is a system where the government provides cash transfers to individuals or families with income below a certain threshold. The amount of transfer gradually decreases as income rises, until it reaches zero. This system aims to provide support to those who need it most, while incentivizing work and reducing the welfare trap. The idea was first proposed by economist Milton Friedman.

UBI, on the other hand, is a system where every citizen or resident of a country receives a fixed amount of money from the government, regardless of their income or employment status. This system aims to provide a basic level of income security to everyone, reduce poverty, and promote social cohesion. UBI has been proposed by various thinkers and policymakers, including Martin Luther King Jr. and Andrew Yang.[24]

Key differences between NIT and UBI:

- Targeting: NIT is targeted towards those who are most in need, based on their income level. UBI, on the other hand, is universal, and everyone receives the same amount, regardless of their income or wealth.[25]

- Cost: NIT is generally considered to be less expensive than UBI, since it targets a smaller group of people. UBI, by contrast, would require a much larger budget, since it is provided to everyone.[26]

- Work Incentives: NIT is designed to provide incentives for people to work, since the transfer gradually decreases as income rises. UBI, by contrast, is often criticized for potentially discouraging work, since everyone receives the same amount, regardless of whether they are employed or not.[27]

- Administrative Complexity: NIT requires a more complex system of means testing and income verification, since it is targeted towards specific income groups. UBI, by contrast, is simpler to administer, since everyone receives the same amount.[28]

Overall, the choice between NIT and UBI will depend on a variety of factors, including political priorities, budget constraints, and the social and economic context of the country.[29]

References

- Moffitt, Robert A (2003-08-01). "The Negative Income Tax and the Evolution of U.S. Welfare Policy". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 17 (3): 119–140. doi:10.1257/089533003769204380. ISSN 0895-3309.

- Alston, Richard M.; Kearl, J.R.; Vaughan, Michael B. (May 1992). "Is There a Consensus Among Economists in the 1990s?" (PDF). The American Economic Review. American Economic Association. 82 (2): 203–09. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- Manuale di Economia Politica con una Introduzione alla Scienza Sociale (1906) / Manuel d'Économie Politique (1909), §53 and §55 of Chap. VI.

- O. Lange, "The Foundations of Welfare Economics" (1942).

- P. A. Samuelson, "Foundations of Economic Analysis" (1947), pp. 219–249.

- See Edwin G. West, "Property Rights in the History of Economic Thought: From Locke to J.S. Mill" (2001/2003).

- Sir J. Mirrlees, "An Exploration in the Theory of Optimum Income Taxation" (1971).

- E. Sheshinski, "The Optimal Linear Income Tax" (1972).

- M. Friedman assisted by R. Friedman, "Capitalism and Freedom" (1961), pp. 190–195.

- Milton Friedman - The Negative Income Tax, retrieved 2021-04-30

- M. Friedman, "The Case for Negative Income Tax: A View from the Right" (1966). Republished several times.

- Suplicy, Eduardo (June 2000). "Eduardo Suplicy's Interview With Milton Friedman". The U.S. Basic Income Guarantee NewsFlash.

- Leland Neuberg, "Emergence and Defeat of Nixon's Family Assistance Plan" (2004) https://usbig.net/papers/066-Neuberg-FAP2.doc.

- Robins, Philip K. (1985). "A Comparison of the Labor Supply Findings from the Four Negative Income Tax Experiments". The Journal of Human Resources. 20 (4): 567–582. doi:10.2307/145685. ISSN 0022-166X. JSTOR 145685.

- Greenberg, D.; Moffitt, R. (1983). "The New Jersey Income Maintenance Experiment: A Review and Evaluation" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- Haveman, Robert (1974). "The Rural Income Maintenance Experiment: Methodology and Summary of Findings". Journal of Human Resources. 9 (3): 264–280. doi:10.2307/144924. JSTOR 144924.

- Haveman, R.; Barsky, Robert; Beggs, John; Duncan, Gregory M.; Dowd, B.; Killingsworth, Mark R. (1978). "The Seattle-Denver Income Maintenance Experiment: Overview, Evaluation, and Future Prospects". Journal of Human Resources. 13 (4): 463–499. JSTOR 145527. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- Forget, Evelyn L. (2011). "The Mincome Experiment: Big Lessons for Basic Income" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Economics. 44 (4): 1078–1098. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5982.2011.01683.x. S2CID 153257768.

- Matthews, Dylan (2014-07-23). "Paying everyone enough to escape poverty is doable". Vox. Retrieved 2021-04-30.

- Burtless, Gary (1986). "The work response to a guaranteed income: a survey of experimental evidence". In Munell, Alicia H. (ed.). Lessons from the income maintenance experiments. Conference Series; [Proceedings]. Vol. 30. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. pp. 22–59.

- Solow, Robert M. (1986). "An economist's view of the income maintenance experiments". In Munell, Alicia H. (ed.). Lessons from the income maintenance experiments. Conference Series; [Proceedings]. Vol. 30. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. pp. 218–226.

- Harvey, Philip (December 2006). "The Relative Cost of a Universal Basic Income and a Negative Income Tax" (PDF). Basic Income Studies. 1 (2). doi:10.2202/1932-0183.1032. S2CID 154259702.

- Hammond, Samuel (9 June 2016). ""Universal Basic Income" is Just a Negative Income Tax with a Leaky Bucket". Niskanen Center. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Gopalan, Shivaji (29 November 2019). "The fundamental differences between a negative income tax and a universal basic income". The Conversation. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Hammond, Samuel (9 June 2016). ""Universal Basic Income" is Just a Negative Income Tax with a Leaky Bucket". Niskanen Center. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Gopalan, Shivaji (29 November 2019). "The fundamental differences between a negative income tax and a universal basic income". The Conversation. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Gopalan, Shivaji (29 November 2019). "The fundamental differences between a negative income tax and a universal basic income". The Conversation. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Hammond, Samuel (9 June 2016). ""Universal Basic Income" is Just a Negative Income Tax with a Leaky Bucket". Niskanen Center. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Gopalan, Shivaji (29 November 2019). "The fundamental differences between a negative income tax and a universal basic income". The Conversation. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

Further reading

- Edmund Phelps (ed.), "Economic Justice", selected readings (1973), esp. Part Five (mathematical).

- Tony Atkinson, "Inequality" (2015).