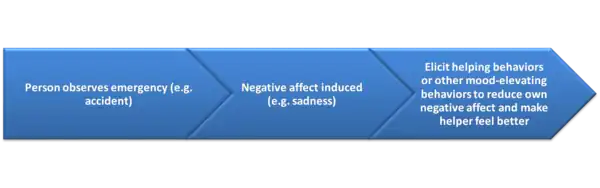

Negative-state relief model

The negative-state relief model states that human beings have an innate drive to reduce negative moods. They can be reduced by engaging in any mood-elevating behaviour, including helping behaviour, as it is paired with positive value such as smiles and thank you. Thus negative mood increases helpfulness because helping others can reduce one's own bad feelings.[1]

Supporting evidence

In a classic experiment, subjects had their negative mood induced and were given an opportunity to help others. Between negative mood induction and helping, half of the subjects received something pleasurable, while the others did not. Those subjects without gratifying intervention before helped more significantly than those with. It was argued that the pleasurable intervention relieved subjects’ mood, and hence, altruism was not required to elevate their mood.[2]

Under negative state relief model, helping behaviours are motivated by one's egoistic desires. In Manucia's 1979 study, the hedonistic nature of helping behaviour was revealed and negative relief model was supported. Subjects were divided into 3 groups – happy, neutral and sad mood groups. Half of the subjects in each group were made to believe that their induced mood was fixed temporarily. Another half group believed that their mood was changeable. The results showed that saddened subjects helped more when they believed that their mood was changeable. The results supported the egoistic nature of helping behaviours as well as the negative state relief model.[3]

Hedonistic nature of negative state relief model was supported in some literatures. For example, Weyant found in 1978 that negative mood induction increased helping in his subjects when the cost of helping was low and the benefits were high.[4] In an experiment with school children subjects, negative mood led to increased helping only when the helping opportunity offered the chance of direct social reward for their generosity.[5]

It was found in another study that empathic orientation to the suffering increased one's personal sadness. Despite high level of empathy, when the subjects were made to perceive their sadness as unchangeable, they helped less. Helping behaviors were predicted well by one's sad mood rather than the empathy level.[6]

Challenges

There have been challenges on the negative state relief model since 1980's. Daniel Batson and his associates found in 1989 that, regardless of anticipated mood enhancement, high-empathy subjects helped more than low-empathy subjects. In other words, high-empathy subjects would still helped more either under easy escape conditions or even when they could probably get good mood to relieve from negative state without helping. Therefore, they concluded that, obviously, something other than relieving negative state was motivating the helping behavior of the high-empathy subjects in their studies.[7] It contradicted with the theory proposed by Robert Cialdini in 1987[6] which supported that empathy-altruism hypothesis was actually the product of an entirely egoistic desire for personal mood management.

Many researchers have challenged the generalizability of the model. It was found that effect of negative state relief on helping behaviour varied with ages.[8] For very young children, a negative mood would not increase their helpfulness because they had not yet learned to associate pro-social behaviour with social rewards. Grade-school children who had been socialized to an awareness of the helping norm (but had not fully internalized it) would help more in response to negative affect only when someone gave them reinforcements or rewards.[5] For adults, however, helpfulness has become self-reinforcing; therefore, a negative mood reliably increased helping. However, according to the study conducted by Kenrick, negative emotions in children promoted their helping behaviours if direct rewards were possibly provided for their pro-social behaviours.[5]

Negative affect was treated as a generalized state in negative state relief model.[9] Specific types of negative feelings that increase helping - guilt, embarrassment, or awareness of cognitive inconsistency,[10][11][12] were not viewed as uniquely important. They just fell within the general category of negative mood.[8] According to the model, not all negative feeling states boost helping. For instance, anger and frustration, naturally elicited responses contradictory to helping, would not increase helping.[13]

Example

On 26 Dec 2004, there was a great tsunami striking the coasts of most landmasses bordering the Indian Ocean, killing more than 225,000 people in eleven countries. It was one of the deadliest natural disasters in history. Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, and Thailand were among approximately 14 countries to experience the death of thousands of locals and tourists. After the propagation of the sorrowful news, people around the world initiated donation campaigns immediately. Besides donations from governments, the public donated at the same time. For example, in the first few days, British donated 1 million pounds. Overall, the public around the world donated US$470 million. The sight of victims in media caused negative emotion, like the sadness over deaths, on the donors. Therefore, their donation helped reduce these negative feelings according to the model.

Besides the disaster mentioned above, there are also daily examples. When a person sitting in a bus witnesses a pregnant woman or an old person standing, negative affect will be induced on the witness. Giving seat to the persons in need can instrumentally restore the bystander's mood as helping contains a rewarding component for most socialized people.

Future study direction and conclusion

The nature of helping has been debated for a long time. On the one hand, under the negative state relief model, the ultimate goal of helping is to relieve bystander's negative mood, thus, pro-social behaviours are viewed as the results of helper's selfishness and egoism. On the other hand, some disagree with this stance, and think that empathy, other than negative states, leads to helping behaviours. The debate continues, and it is thought that there is still a long run before reaching a consensus on the nature of helping.

In recent years, a large body of researches showed that motivations to help are different in different relationships and across different contexts. For example, it was found that empathic concern was linked to the willingness to help kin but not a stranger when egoistic motivators were controlled.[14] To get a more comprehensive view, future studies should test the negative state relief model under different contexts. Such explorations would be crucial to dig out the contextual effects and psychological factors underlying prosocial behaviors.

References

- Baumann, D. J.; Cialdini, R. B.; Kenrick, D. T. (1981). "Altruism as hedonism: Helping and self-gratification as equivalent responses". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 40 (6): 1039–1046. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.40.6.1039.

- Cialdini, R. B.; Darby, B. L.; Vincent, J. E. (1973). "Transgression and altruism: A case for hedonism". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 9 (6): 502–516. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(73)90031-0.

- Manucia, G. K.; Baumann, D. J.; Cialdini, R. B. (1984). "Mood influences on helping: direct effects or side effects?". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 46 (2): 357–364. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.46.2.357. S2CID 13091062.

- Weyant, J. M. (1978). "Effects of mood states, costs, and benefits on helping". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 36 (10): 1169–1176. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.36.10.1169.

- Kenrick, D. T.; Baumann, D. J.; Cialdini, R. B. (1979). "A step in the socialization of altruism as hedonism: effects of negative mood on children's generosity under public and private conditions". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 37 (5): 747–755. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.5.747.

- Cialdini, R. B.; Schaller, M.; Houlihan, D.; Arps, K.; Fultz, J.; Beaman, A. L. (1987). "Empathy-based helping: is it selflessly or selfishly motivated?". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 52 (4): 749–758. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.4.749. PMID 3572736.

- Batson, C. D.; Batson, J. G.; Grittitt, C. A.; Barrientos, S.; Brandt, J. R.; Sprengelmeyer, P.; Bayly, M. J. (1989). "Negative-state relief and the empathy-altruism hypothesis". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 56 (6): 922–933. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.6.922.

- Cialdini, R. B.; Kenrick, D. T. (1976). "Altruism as hedonism: A social development perspective on the relationship of negative mood state and helping". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 34 (5): 907–914. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.34.5.907. PMID 993985.

- Carlson, M.; Miller, N. (1987). "Explanation of the relation between negative mood and helping". Psychological Bulletin. 102: 91–108. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.102.1.91.

- Apsler, R. (1975). "Effects of embarrassment on behavior toward others". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 32: 145–153. doi:10.1037/h0076699.

- Carlsmith, J.; Gross, A. (1969). "Some effects of guilt on compliance". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 11 (3): 232–239. doi:10.1037/h0027039. PMID 5784264. S2CID 34274726.

- Kidd, R.; Berkowitz, L. (1976). "Effect of dissonance arousal on helpfulness". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 33 (5): 613–622. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.33.5.613.

- Cialdini, R. B.; Baumann, D. J.; Kenrick, D. T. (1981). "Insights from sadness: A three-step model of the development of altruism as hedonism". Developmental Review. 1 (3): 207–223. doi:10.1016/0273-2297(81)90018-6.

- Maner, J.; Gailliot, M. (2007). "Altruism and egoism: prosocial motivations for helping depend on relationship context". European Journal of Social Psychology. 37 (2): 347–358. doi:10.1002/ejsp.364.