Nesyamun

| Nesyamun | |

|---|---|

| God's father of Montu Scribe of the temple of Montu Scribe who lays out offerings Scribe who keeps tally of the cattle | |

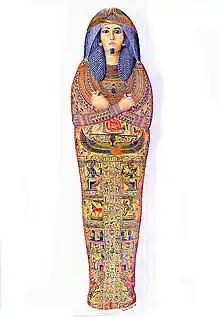

An artist's rendering of how the coffin lid of Nesyamun might have originally looked. The effect is intended to recall the illustrations made by Napoleon's surveyors in the Description of Egypt. | |

| Dynasty | 20th Dynasty |

| Pharaoh | Ramesses XI |

| Burial | Likely Deir el-Bahari |

| Nesyamun[1] in hieroglyphs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Nesyamun, also known as Natsef-Amun or The Leeds Mummy, was an Ancient Egyptian priest who lived during the Twentieth Dynasty c. 1100 BC. He was a senior member of the temple administration in the Karnak temple complex and held various titles including "god's father of Montu" and "scribe of Montu", and was responsible for presenting the daily food offerings to the gods and tallying the cattle of the Karnak temple estates. Nothing is known about his family.

His body was discovered in the early 1820s during excavations of the Deir el-Bahari causeway by Giuseppe Passalacqua. He was shipped to Europe and sold several times before being purchased for the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society's museum in Leeds, England. In 1824 his coffin and mummy was the subject of one of the earliest scientific investigations of an Egyptian mummy. His remains are now held in the collection of the Leeds City Museum. Study of his coffin and mummy cover found them to be of high quality. Nesyamun was the only one of the museum's mummies to remain intact following the 1941 Leeds Blitz, although his mummy cover sustained major damage. From the 1930s onward he has undergone various forms of testing which has revealed his general state of health and that he died aged between 50 and 60 years. In 2020, his mummified vocal tract was modelled using CT scan data, allowing it to produce a single sound; the study attracted criticism for its ethics and research value.

Life

Nesyamun (meaning "the one belonging to Amun"[2]) was a priest and scribe working within the Egyptian temple complex of Karnak in Thebes. He lived during the Twentieth Dynasty, when Thebes was ruled by the High Priest of Amun.[3] His most senior titles related to the cult of Montu, the Theban war god, as "god's father of Montu" and "scribe of the temple of Montu." He also had roles within the wider temple complex as "scribe who lays out offerings for all the gods of Upper and Lower Egypt", and "scribe who keeps tally of the cattle of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu".[4] He was also an incense-bearer and possibly a wab-priest.[5][Note 1] His titles indicate that he was a senior member of the temple administration.[4]

Nothing is known of his family and no mention is made of them in the inscriptions on his coffin.[4] According to the 1854 museum guidebook, inscriptions from his tomb mentioned that Nesyamun married the daughter of Amenemtephis who held one of the highest positions at the "Memnonium".[7] Nesyamun's son succeeded his grandfather Amenemtephis in this role.[8] Nesyamun died around 1100 BC and was buried in the cemetery of priests and priestesses of Amun in the causeway of Hatshepsut's mortuary temple Deir el-Bahari.[9][10]

Modern history

The coffined body of Nesyamun was rediscovered in 1822 or 1823 by Italian trader Giuseppe Passalacqua during his excavations of the Deir el-Bahari causeway. He was then sent, with another mummy, from Egypt to Trieste in 1823.[11] Nesyamun was bought in 1823 in London by antiquities dealer William Bullock from another man who had purchased and transported the mummy to England.[12] In 1824 he was bought for the final time by the banker John Blayds for the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society's museum.[13] Nesyamun was their second mummy, as the mummy of "Pethor", excavated at Thebes by Henry Salt in 1822, was obtained in February of 1823.[14]

Nesyamun's coffin was opened in late 1824 and his mummy was investigated by members of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society.[15] Published in 1828, his autopsy was "one of the earliest scientific examinations to be undertaken on an Egyptian mummy".[16] The report was multidisciplinary, noting how the body was unwrapped and autopsied, the features of the mummy, with notes made on the wrappings and artefacts within them, and described and attempted a translation and explanation of the hieroglyphic texts and scenes on the coffin.[16] His name was written as "Natsif-Amon".[17]

He was placed on display on the first floor of the museum and is mentioned in the 1854 guidebook under the name "Ensa-Amoun".[7] From the 1860s he was displayed in the vestibule. In the 1890s, the coffin and mummy were examined by the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie, who stated that the coffins dated to the reign of Amenhotep III but were reused for a later mummy of the reign of Ramesses XII. In the 1930s he was moved and redisplayed in a new case.[18] Nesyamun was the only mummy without significant damage after the Leeds Blitz bombing of 15 March 1941 destroyed the front half of the museum. The bomb blast destroyed the red leather ornament found within his wrappings, broke his mummy cover into pieces and covered his body in debris but the coffin trough and lid sustained only minor damage. The two other mummies held by the museum were destroyed in the blast.[19][20] In the late 1960s Nesyamun was moved to the new museum building.[19]

In 1990, the director of Leeds City Museum invited the Manchester Mummy Team led by Rosalie David to undertake a new scientific study of Nesyamun (then known as "Natsef-Amun").[21] The multi-disciplinary team, established in 1973,[22] used a variety of techniques including X-rays, CT scans, and analysis of tissue samples to determine Nesyamun had arthritis in his neck and hip and was infected with a type of parasitic worm. Forensic facial reconstruction was also carried out; the bust produced depicts him as he may have looked at the time of his death.[23]

Since 2002, the Leeds Museum has been documenting and researching both the decoration upon the coffin, and the coffin itself. This has led to a greater understanding of the nature of the roles that Nesyamun, as a priest at the temple of Karnak, would have played.

In 2008, the mummy was moved to a new home at the Leeds City Museum.

Coffin and cover

Nesyamun's preserved body was entombed in a high quality wooden coffin inscribed with hieroglyphs.[24] It is likely constructed of multiple pieces of sycomore fig wood smoothed over with gypsum plaster.[25][26] The background colour is yellow and the texts and scenes are executed in bright colours.[25] The coffin is mummiform in shape and depicts Nesyamun wearing a large wig encircled with a floral fillet and topped with lotus flowers. He had a short beard on his chin which is depicted in the 1828 publication but has since broken off. Across his chest is a broad collar with a central scarab. His arms are crossed over his chest and he wears bracelets at the wrists and elbows. His hands are fisted, as is typical for male coffins of this era.[27] The hands presumably held amulets, likely ankhs, tyet-knots, or djed-pillars but are no longer present.[28] Below the arms is a solar barque in which Amun-Re rides, and immediately below is the kneeling goddess Nut with outstretched wings.[29][26]

The lid is divided with central and horizontal bands of text mimicking the placement of the wide bands seen on mummy wrappings. The space between the inscriptions is filled with scenes of Nesyamun presenting offerings to various funerary gods including Ra-Horakhty, Osiris, and the four sons of Horus.[30] Nesyamun's name and titles were not added into blanks in a pre-made coffin but written all in one, probably by a single person based on the consistent handwriting.[24] The decorative scheme is divided into "eastern" and "western" themes between the left and right sides on the lid and trough with the depiction of paired day and night forms of gods.[31] Isis and Nephthys are depicted individually at their respective head and foot ends of the coffin, and both appear on the top of the feet and adoring a djed-pillar on the foot board of the trough.[32] The central vertical lid inscription addresses the goddess Nut, asking for eternal life and to not die a second death.[29] The left and right vertical columns ask to be able to go out to see the sun and to join the gods Osiris and Sokar and receive offerings. The rest of the inscriptions follow a similar theme, asking for offerings and freedom of movement to see the gods.[33] One text asks specifically to attend a festival of the god Sokar, with "onions at my neck the day of going round the walls".[34] The underside of coffin base is undecorated, as is the interior, which is painted black.[27]

The mummy cover[Note 2] depicts Nesyamun wrapped in white fabric like a mummy. It again has the likeness of the deceased, wearing a wig and floral headband. Across his chest is a broad collar and winged scarab. Below is a barque carrying a solar scarab flanked by Isis and Nephthys.[26] Again, Nut is depicted kneeling below, spreading her wings protectively. Its inscriptions are similar to those on the coffin, with two columns of vertical hieroglyphs invoking the goddess Nut with the same text as the coffin lid.[35]

The coffin is generally in good condition. A crack runs down the body on the proper right side and modern repairs are evident on the lid at the feet, right shoulder, and left edge, which obscures the text. The mummy cover was badly damaged in a bomb blast in 1941. It was originally white but is now painted black, possibly to hide damage.[24]

Mummy

Initial examination

Nesyamun's wrapped mummy was first examined in 1824 by William Osburn, E. S. George, T. P. Teale, and R. Hey, members of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. They found the body to be wrapped in many layers of linen fabric, "nowhere less than forty thicknesses".[36] The outermost layer was a shroud of fine white fabric. Below this was between five and six layers of wide resin-treated bandages and beneath these were further layers of the same wide bandaging.[36] Enclosed within these were two floral garlands. They consisted of nine strings each of red berries with lotus petals, and lotus petals and "globular" flowers respectively.[37][38] In the wrappings over his face and on his head was found a brittle red leather ornament decorated with figures of gods and the dual cartouches of Ramesses XI.[39][40] One piece was shaped like a bunch of lotuses, and the whole functioned perhaps an emblem of his position.[5] The bandaging was made from recycled clothing, showing evidence of seams and repairs, and an entire tunic was used as padding on the front of the body and another garment padded the space between the legs.[41] Some of the textiles may also have derived from temple linen.[42]

When the body was revealed, it was covered with a 1 inch (2.5 cm) thick "layer of spicery" which Osburn noted "still retains the faint smell of cinnamon and cassia".[43] The body cavity, mouth and skull filled were with the same substance. The mummy was found to be well preserved, with the skin being a "grey colour, soft and greasy to the touch".[44] The team observed that the impression of bandages could be seen across the face and that all the hair on his head, including his eyebrows, was closely shaved. His mouth is slightly open and his tongue sticks out over his teeth.[44] The brain was removed through the right nostril. His organs were removed through an incision on his left side, and the dried and wrapped organ packets were placed within the body cavity.[45][46]

Later examinations

Nesymaun was first X-rayed in 1931–32 and again in 1964. In 1989 he was re-examined as part of the Manchester Mummy Project.[47] The back of the skull was found to have been removed in 1824 by Osburn's investigation.[48] His teeth were worn, as is expected for an ancient Egyptian of his age, and he had lost some of his molars.[49] He also had wear between his teeth, resulting in his front teeth becoming peg-like in shape. The suggested causes are consumption of acidic fruit or over-zealous and regular cleaning of his teeth with a frayed stick. Despite this, he had gum disease, which had signs of infection, but no cavities suggesting a low-sugar diet.[50]

Examination of his eyes found degradation of the nerves suggestive of peripheral neuritis which can be caused by conditions such as diabetes and vitamin deficiency.[51] Serology testing found he had O-type blood.[52]

He had a narrowed intervertebral disc and associated osteophytes between the 5th and 6th cervical vertebrae which would have caused pain. His arms were extended with the hands placed over the front of his thighs, although his hands were removed by Osburn in 1824.[48] Based on his manicured and hennaed nails, he did not engage in much physical labour.[46] His lumbar spine is disarticulated due to modern damage. His left hip has dislocated post mortem but has evidence of osteoarthritis. His feet are normal but are slightly misshapen by tight bandaging.[53]

Tissue samples from his groin revealed an infection of parasitic Filarioidea worms that cause the disease filariasis. This condition, also called lymphatic filariasis or elephantiasis can cause swelling in the legs and groin but it could not be determined if Nesyamun had it due to the skin and tissue shrinkage caused by mummification.[54] The major part of his abdominal wall was removed during Osburn's investigation.[55] The organ packages mentioned and examined in 1824 were not returned to the body cavity so they could not be examined and further evidence of disease is unknown.[56] He had hardening of the arteries (atherosclerosis) in the large arteries of his groin, a disease that can cause heart attacks or strokes.[21]

Nesyamun was 5 feet 6 inches (168 cm) tall in life[46] and died in middle age, between 40 and 50 years old.[21] His cause of death is unknown but his protruding tongue is unusual. The mouth was usually closed after death and before mummification. This has led to the suggestion that Nesyamun died a violent death such as by strangulation, but the hyoid bone in his throat is intact and this is usually damaged in cases of strangulation.[57] Instead, he may have died when his tongue swelled, possibly caused by disease or an allergic reaction.[58]

Voice reconstruction

In 2020, Nesyamun's vocal tract was 3D printed using data from a 2016 CT scan. This model, which replicates his mummified mouth and throat, was used to produce a simulated vowel sound to represent how the priest's voice may sound in his current state.[59][60] Egyptologists have questioned the ethics and value of the project,[61] with Christina Riggs commenting via Twitter that the desecration of mummies is "alive and well" and that "only the rationalisations and tech" have changed.[62]

Notes

Citations

- Porter & Moss 1964, p. 637.

- Wassell 2008, p. 4.

- David 1992b, p. 68.

- Wassell 2008, p. 10.

- David 1992b, p. 65.

- Wassell 2008, p. 14.

- Brears 1992, p. 89.

- David 1992b, p. 78.

- Cardin 2015, p. 327.

- David 1992a, p. 58.

- David 1992a, pp. 58–59.

- Brears 1992, p. 83.

- Brears 1992, pp. 83–84.

- Brears 1992, pp. 81–82.

- Brears 1992, pp. 84–85.

- David 1992a, p. 59.

- Osburn 1828, p. 26.

- Brears 1992, p. 90.

- Brears 1992, pp. 90–91.

- Sheerin 2019.

- David 2005, p. 176.

- David 1979.

- David 2005, pp. 176–178.

- Wassell 2008, p. 8.

- Wassell 2008, p. 5.

- David 1992a, p. 60.

- Wassell 2008, p. 6.

- Wassell 2008, p. 7.

- Wassell 2008, p. 26.

- Wassell 2008, pp. 7, 29–32.

- Wassell 2008, p. 18.

- Wassell 2008, p. 19.

- Wassell 2008, p. 20.

- Wassell 2008, p. 21.

- Wassell 2008, p. 40.

- Osburn 1828, p. 3.

- Osburn 1828, pp. 3–4.

- David 1992a, p. 61.

- Osburn 1828, pp. 4–5.

- David 1992a, p. 63.

- Osburn 1828, pp. 5–6.

- Wassell 2008, p. 9.

- Osburn 1828, p. 6.

- Osburn 1828, p. 7.

- Osburn 1828, p. 8.

- David 1992a, p. 64.

- Brears 1992, p. 92.

- Isherwood & Hart 1992, p. 106.

- Miller & Asher-McDade 1992, p. 117.

- Miller & Asher-McDade 1992, pp. 118–120.

- Tapp & Wildsmith 1992, p. 147.

- Haigh & Flaherty 1992, p. 161.

- Isherwood & Hart 1992, p. 109.

- Tapp & Wildsmith 1992, p. 151.

- Tapp & Wildsmith 1992, p. 148.

- Tapp & Wildsmith 1992, pp. 148, 153.

- Miller & Asher-McDade 1992, pp. 116–117.

- David 2005, p. 177.

- Howard et al. 2020.

- Lewis 2020.

- Matić 2021.

- Kannenberg 2022, p. 332.

References

- Brears, P. C. D. (1992). "The Dental Examination of Natsef-Amun". In David, A. R.; Tapp, E. (eds.). The Mummy's Tale: The Scientific and Medical Investigation of Natsef-Amun, Priest in the Temple at Karnak (1993 US ed.). New York : St. Martin's Press. pp. 112–120. ISBN 978-0-312-09061-6.

- Cardin, Matt, ed. (2015). Mummies around the World: An Encyclopedia of Mummies in History, Religion, and Popular Culture: An Encyclopedia of Mummies in History, Religion, and Popular Culture. ABC-CLIO. pp. 327–328. ISBN 978-1-61069-420-9.

- David, A. Rosalie, ed. (1979). The Manchester Museum Mummy Project : multidisciplinary research on ancient Egyptian mummified remains (PDF). Manchester, England: Manchester Museum. ISBN 0-7190-1293-7. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- David, A. R. (1992a). "The Discovery and 1828 Autopsy of Natsef-Amun". In David, A. R.; Tapp, E. (eds.). The Mummy's Tale: The Scientific and Medical Investigation of Natsef-Amun, Priest in the Temple at Karnak (1993 US ed.). New York : St. Martin's Press. pp. 55–64. ISBN 978-0-312-09061-6.

- David, A. R. (1992b). "Natsef-Amun's Life as a Priest". In David, A. R.; Tapp, E. (eds.). The Mummy's Tale: The Scientific and Medical Investigation of Natsef-Amun, Priest in the Temple at Karnak (1993 US ed.). New York : St. Martin's Press. pp. 65–79. ISBN 978-0-312-09061-6.

- David, A. Rosalie (2005). "Natsef-Amun, keeper of the bulls: a comparative study of the paleopathology and archaeology of an Egyptian mummy". Journal of Biological Research – Bollettino della Società Italiana di Biologia Sperimentale. 80 (1). doi:10.4081/jbr.2005.10177. ISSN 2284-0230. S2CID 239525800.

- David, A. R.; Tapp, E. (1992). The Mummy's Tale : the scientific and medical investigation of Natsef-Amun, priest in the temple at Karnak (1993 US ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-09061-6. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- Haigh, T.; Flaherty, T. A. (1992). "Blood Grouping". In David, A. R.; Tapp, E. (eds.). The Mummy's Tale: The Scientific and Medical Investigation of Natsef-Amun, Priest in the Temple at Karnak (1993 US ed.). New York : St. Martin's Press. pp. 154–161. ISBN 978-0-312-09061-6.

- Howard, D. M.; Schofield, J.; Fletcher, J.; Baxter, K.; Iball, G. R.; Buckley, S. A. (23 January 2020). "Synthesis of a Vocal Sound from the 3,000 year old Mummy, Nesyamun 'True of Voice'". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 45000. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1045000H. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-56316-y. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6978302. PMID 31974412.

- Isherwood, Ian; Hart, C. W. (1992). "The Radiological Investigation". In David, A. R.; Tapp, E. (eds.). The Mummy's Tale: The Scientific and Medical Investigation of Natsef-Amun, Priest in the Temple at Karnak (1993 US ed.). New York : St. Martin's Press. pp. 100–111. ISBN 978-0-312-09061-6.

- Kannenberg, John (2022). "Listening to Archaeology Museums". In Stevenson, Alice (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Museum Archaeology. Oxford University Press. pp. 328–352. ISBN 978-0-19-258675-9.

- Lewis, Sophie (23 January 2020). "Listen to the sound of a 3,000-year-old Egyptian mummy". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- Malsbury, Erin (23 January 2020). "The dead speak! Scientists re-create voice of 3000-year-old mummy". Science. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- Matić, Uroš (June 2021). "Talk like an Egyptian? Epistemological problems with the synthesis of a vocal sound from the mummified remains of Nesyamun and racial designations in mummy studies". Archaeological Dialogues. 28 (1): 37–49. doi:10.1017/S1380203821000076. S2CID 234364919.

- Miller, Judith; Asher-McDade, Catherine (1992). "The Dental Examination of Natsef-Amun". In David, A. R.; Tapp, E. (eds.). The Mummy's Tale: The Scientific and Medical Investigation of Natsef-Amun, Priest in the Temple at Karnak (1993 US ed.). New York : St. Martin's Press. pp. 112–120. ISBN 978-0-312-09061-6.

- Osburn, William (1828). An Account of an Egyptian Mummy, Presented to the Museum of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. Leeds: Robinson & Hernaman. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- Porter, Bertha; Moss, Rosalind L. B. (1964). Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings I: The Theban Necropolis Part 2: Royal Tombs and Smaller Cemeteries (Second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Sheerin, Joseph (22 April 2019). "3 Forgotten Stories From Leeds' Past". Leeds-List. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Tapp, E.; Wildsmith, K. (1992). "The Autopsy and Endoscopy of the Leeds Mummy". In David, A. R.; Tapp, E. (eds.). The Mummy's Tale: The Scientific and Medical Investigation of Natsef-Amun, Priest in the Temple at Karnak (1993 US ed.). New York : St. Martin's Press. pp. 132–153. ISBN 978-0-312-09061-6.

- Wassell, Belinda (2008). The Coffin of Nesyamun, the "Leeds mummy" : (LEEDM. D.1960.426). Leeds: Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. ISBN 978-1-870737-21-0.