Neurosis

Neurosis (PL: neuroses) is a term mainly used today by followers of Freudian thinking to describe mental disorders caused by past anxiety, often that has been repressed. In recent history, the term has been used to refer to anxiety-related conditions more generally.

| Neurosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Psychoneurosis, neurotic disorder |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

The term "neurosis" is no longer used in condition names or categories by the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD) or the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). According to the American Heritage Medical Dictionary of 2007, the term is "no longer used in psychiatric diagnosis".[1]

Neurosis is distinguished from psychosis, which refers to a loss of touch with reality. Its descendant term, neuroticism, refers to a personality trait of being prone to anxiousness and mental collapse. The term "neuroticism" is also no longer used for DSM or ICD conditions; however, it is a common name for one of the Big Five personality traits. A similar concept is included in the ICD-11 as the condition "negative affectivity".

History

A broad condition (1769-1879)

The term neurosis was coined by Scottish doctor William Cullen to refer to "disorders of sense and motion" caused by a "general affection of the nervous system". The term is derived from the Greek word neuron (νεῦρον, 'nerve') and the suffix -osis (-ωσις, 'diseased' or 'abnormal condition'). It was first used in print in Cullen's System of Nosology, first published in Latin in 1769.[2]

Cullen used the term to describe various nervous disorders and symptoms that could not be explained physiologically. Physical features, however, were almost inevitably present, and physical diagnostic tests, such as exaggerated knee-jerks, loss of the gag reflex and dermatographia, were used into the 20th century.[3]

French psychiatrist Phillipe Pinnel's Nosographie philosophique ou La méthode de l'analyse appliquée à la médecine (1798) was greatly inspired by Cullen. It divided medical conditions into five categories, with one being "neurosis". This was divided into four basic types of mental disorder: melancholia, mania, dementia, and idiotism.[2]

Morphine was first isolated from opium in 1805, by German chemist Friedrich Sertürner. After the publication of his third paper on the topic in 1817,[4] morphine became more widely known, and used to treat neuroses and other kinds of mental distress.[5][6] After becoming addicted to this highly addictive substance, he warned "I consider it my duty to attract attention to the terrible effects of this new substance I called morphium in order that calamity may be averted."[7]

German psychologist Johann Friedrich Herbart used the term repression in 1824, in a discussion of unconscious ideas competing to get into consciousness.[8]

The tranquilising properties of potassium bromide were noted publicly by British doctor Charles Locock in 1857. Over the coming decades, this and other bromides were used in great quantities to calm people with neuroses.[6][9][10] This led to many cases of bromism.

Breuer, Freud and contemporaries (1880-1939)

Austrian psychiatrist Josef Breuer first used psychoanalysis to treat hysteria in 1880–1882.[11] Bertha Pappenheim was treated for a variety of symptoms that began when her father suddenly fell seriously ill in mid-1880 during a family holiday in Ischl. His illness was a turning point in her life. While sitting up at night at his sickbed she was suddenly tormented by hallucinations and a state of anxiety.[12] At first the family did not react to these symptoms, but in November 1880, Breuer, a friend of the family, began to treat her. He encouraged her, sometimes under light hypnosis, to narrate stories, which led to partial improvement of the clinical picture, although her overall condition continued to deteriorate.

According to Breuer, the slow and laborious progress of her "remembering work" in which she recalled individual symptoms after they had occurred, thus "dissolving" them, came to a conclusion on 7 June 1882 after she had reconstructed the first night of hallucinations in Ischl. "She has fully recovered since that time" were the words with which Breuer concluded his case report.[13] Accounts differ on the success of Pappenheim's treatment by Breuer. She did not speak about this episode in her later life, and vehemently opposed any attempts at psychoanalytic treatment of people in her care.[14] Breuer was not quick to publish about this case.

(Subsequent research has suggested Pappenheim may have had one of a number of neurological illnesses. This includes temporal lobe epilepsy,[15][16][17] tuberculous meningitis,[18] and encephalitis.[17] Whatever the nature of her condition, she went on to run an orphanage, and then found and lead the Jüdischer Frauenbund for twenty years.)

The term psychoneurosis was coined by Scottish psychiatrist Thomas Clouston for his 1883 book Clinical Lectures on Mental Diseases.[19] He describes a condition that covers what is today considered the schizophrenia and autism spectrums (a combination of symptoms that would soon become better known as dementia praecox).

French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot came to believe that psychological trauma was a cause of some cases of hysteria. He wrote in his book Leçons sur les maladies du système nerveux, (1885-1887) (and published in English as Clinical Lectures on the Diseases of the Nervous System):[20]

Quite recently male hysteria has been studied by Messrs. Putnam [1884] and Walton [1883][21] in America, principally as it occurs after injuries, and especially after railway accidents. They have recognised, like Mr. Page, [1885] who in England has also paid attention to this subject, that many of those nervous accidents described under the name of Railway-spine, and which according to them would be better described as Railway-brain, are in fact, whether occurring in man or woman, simply manifestations of hysteria.[20]

Charcot documented around two dozen cases where psychological trauma appears to have caused hysteria.[22] In some cases, the results are described like the modern concept of PTSD.[22]

Austrian psychiatrist Sigmund Freud was a student of Charcot in 1885–6.[23] In 1893 Freud credited Charcot with being the source of "all the modern advances made in the understanding and knowledge of hysteria."[24]

French psychiatrist Pierre Janet released his book L'automatisme psychologique (Psychological automatism) in 1889, its third chapter detailing his understanding of hypnosis and the unconscious. At this time, he claimed that the main aspect of psychological trauma is dissociation (a disconnection of the conscious mind from reality).[25] (Freud would later claim Janet as a major influence.)[26]

In 1891, Thomas Clouston published Neuroses of Development,[27] which covered a wide range of physical and mental developmental conditions.

Breuer came to mentor Freud. The pair released the paper "Ueber den psychischen Mechanismus hysterischer Phänomene. (Vorläufige Mittheilung.)" (known in English as "On the physical mechanism of hysterical phenomena: preliminary communication") in January 1893. It opens with:

A chance observation has led us, over a number of years, to investigate a great variety of different forms and symptoms of hysteria, with a view to discovering their precipitating cause the event which provoked the first occurrence, often many years earlier, of the phenomenon in question. In the great majority of cases it is not possible to establish the point of origin by a simple interrogation of the patient, however thoroughly it may be carried out. This is in part because what is in question is often some experience which the patient dislikes discussing; but principally because he is genuinely unable to recollect it and often has no suspicion of the causal connection between the precipitating event and the pathological phenomenon. As a rule it is necessary to hypnotize the patient and to arouse his memories under hypnosis of the time at which the symptom made its first appearance; when this has been done, it becomes possible to demonstrate the connection in the clearest and most convincing fashion...

It is of course obvious that in cases of 'traumatic' hysteria what provokes the symptoms is the accident. The causal connection is equally evident in hysterical attacks when it is possible to gather from the patient's utterances that in each attack he is hallucinating the same event which provoked the first one. The situation is more obscure in the case of other phenomena.

Our experiences have shown us, however, that the most various symptoms, which are ostensibly spontaneous and, as one might say, idiopathic products of hysteria, are just as strictly related to the precipitating trauma as the phenomena to which we have just alluded and which exhibit the connection quite clearly.[28]

This paper was reprinted and supplemented with case studies in the pair's 1895 book Studien über Hysterie (Studies on Hysteria). Of the book's five case studies, the most famous became that of Breuer's patient Bertha Pappenheim (given the pseudonym "Anna O."). This book established the field of psychoanalysis.

French neurologist Paul Oulmont was mentored by Charcot. In his 1894 book Thérapeutique des névroses (Therapy of neuroses), he lists the neuroses as being hysteria, neurasthenia, exophthalmic goitre, epilepsy, migraine, Sydenham's chorea, Parkinson's disease and tetany.[29]

The fifth edition of German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin's popular psychiatry textbook in 1896 gave "neuroses" a well-accepted definition:[2]

In the following presentation we want to summarize a group of disease states as general neuroses, which are accompanied by more or less pronounced nervous dysfunctions. What is common to these manifestations of insanity is that we are constantly dealing with the morbid processing of vital stimuli; what they also have in common is the occurrence of more transitory, peculiar manifestations of illness, sometimes in the physical, sometimes in the psychic area. These attacks of fluctuations in mental balance are therefore not independent illnesses, but only the occasional increase in a persistent illness... It seems useful to me, for the time being, to distinguish between two main forms of general neuroses, epileptic and hysterical insanity.[30]

Pierre Janet published the two volume work Névroses et Idées Fixes (Neuroses and Fixations) in 1898.[31][32] According to Janet, neuroses could be usefully divided into hysterias and psychasthenias. Hysterias induced such symptoms as anaesthesia, visual field narrowing, paralyses, and unconscious acts.[33] Psychasthenias involved the ability to adjust to one's surroundings, similar to the later concepts of adjustment disorder and executive functions.

Janet founded the French "Société de psychologie"[34] in 1901. This later became the "Société française de psychologie", and continues today as France's main psychology body.[35]

Barbiturate is a class of highly addictive sedative drugs. The first barbiturate, barbital, was synthesized in 1902 by German chemists Emil Fischer and Joseph von Mering and was first marketed as "Veronal" in 1904.[36] Later on, the similar barbiturate phenobarbital was brought to market in 1912 under the name "Luminal". After that, Barbiturate became a popular drug in many countries to reduce neurotic anxiety and displaced the use of bromides.

Janet published the book Les Obsessions et la Psychasthénie (The Obsessions and the Psychasthenias) in 1903.[31] Janet followed this with the books The Major Symptoms of Hysteria in 1907,[37] and Les Névroses (The Neuroses) in 1909.[31]

Janet also co-founded the Journal de psychologie normale et pathologique (Journal of Normal and Pathological Psychology) in 1903.[35]

According to Janet, one cause of neurosis is when the mental force of a traumatic event is stronger than what someone can counter using their normal coping mechanisms.[38]

Meanwhile, Freud developed a number of different theories of neurosis. The most impactful one was that it referred to mental disorders caused by the brain's defence against past psychological trauma.[39] This redefined the general understanding and use of the word. It came to replace the concept of "hysteria".

He held the First Congress for Freudian Psychology in Salzburg in April 1908. Subsequent Congresses continue today.

Freud published the detailed case study "Bemerkungen über einen Fall von Zwangsneurose" (Notes Upon a Case of Obsessional Neurosis) in 1909, documenting his treatment of "Rat Man".

Freud established the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) in March 1910. He arranged for Carl Jung to be its first president. This organisation chose to only provide both psychoanalytic training and recognition to medical doctors.

The American Psychoanalytic Association was founded in 1911[40] by Welsh neurologist Ernest Jones, with the support of Freud. It followed the IPA's practice of only supporting psychoanalysis provided by medical doctors.

Jung gave a speech explaining his understanding of Freud's work called Psychoanalysis and Neurosis in New York in 1912. It was published in 1916.[41]

The journal Internationale Zeitschrift für Psychoanalyse was established in 1913, and continued until 1941.

The battlefield stresses of World War I (1914–18) lead to many cases of strong short-term psychological symptoms, known today as "combat stress reaction" (CSR). Other terms for the condition include "combat fatigue", "battle fatigue", "battle neurosis", "shell shock" and "operational stress reaction". The general psychological term acute stress disorder was first used for this condition at this time.

The fight-or-flight response was first described by American physiologist Walter Bradford Cannon in 1915.[42]

American military psychiatrist Thomas W. Salmon (the chief consultant in psychiatry in the American Expeditionary Force)[43] released the book The care and treatment of mental diseases and war neuroses ("shell shock") in the British army in 1917,[44] dealing primarily with what was considered was the best treatment for hysteria. His recommendations were broadly adopted in the US armed forces.

Freud's most explanatory work on neurosis was his lectures later grouped together as "General Theory of the Neuroses" (1916–17), forming part 3 of the book Vorlesungen zur Einführung in die Psychoanalyse (1917), later published in English as A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis (1920).[45]

In that work, Freud noted that:

The meaning of neurotic symptoms was first discovered by J. Breuer in the study and felicitous cure of a case of hysteria which has since become famous (1880–82). It is true that P. Janet independently reached the same result...

The [neurotic] symptom develops as a substitution for something else that has remained suppressed. Certain psychological experiences should normally have become so far elaborated that consciousness would have attained knowledge of them. This did not take place, however, but out of these interrupted and disturbed processes, imprisoned in the unconscious, the symptom arose...

Our therapy does its work by means of changing the unconscious into the conscious, and is effective only in so far as it has the opportunity of bringing about this transformation...[45]

Freud added to this with his paper "Aus der Geschichte einer infantilen Neurose" (From the History of an Infantile Neurosis) published in 1918, which is a detailed case study of Freud's treatment of the "Wolfman".

The International Journal of Psychoanalysis was founded by Ernest Jones in 1920.

In response to stress injuries from World War I, the British government produced the Report of the War Office Committee of Inquiry into "Shell-Shock", which was published in 1922.

Its recommended course of treatment included:

While recognizing that each individual case of war neurosis must be treated on its merits, the Committee are of opinion that good results will be obtained in the majority by the simplest forms of psycho-therapy, i.e., explanation, persuasion and suggestion, aided by such physical methods as baths, electricity and massage. Rest of mind and body is essential in all cases.

The committee are of opinion that the production of deep hypnotic sleep, while beneficial as a means of conveying suggestions or eliciting forgotten experiences are useful in selected cases, but in the majority they are unnecessary and may even aggravate the symptoms for a time.

They do not recommend psycho-analysis in the Freudian sense.

In the state of convalescence, re-education and suitable occupation of an interesting nature are of great importance. If the patient is unfit for further military service, it is considered that every endeavor should be made to obtain for him suitable employment on his return to active life.

The common neuroses and their treatment by psychotherapy was a book released by British psychiatrist Thomas Arthur Ross[46] in 1923, to instruct medical doctors in general.[47] (A second edition was published in 1937, which was subsequently reprinted many times). He believed that most neuroses can successfully treated by general practitioners, without the need to use "Freudian analysis". He thought that method was only necessary for the most difficult cases. Ross would later write the books Introduction to analytical psychotherapy (1932) and An enquiry into prognosis in the neuroses (1936).

In April 1923 Freud published his monograph Das Ich und das Es (published in English as The Ego and the Id),[48] which included a revised theory of mental functioning, now considering that repression was only one of many defence mechanisms, and that it occurred to reduce anxiety. Hence, Freud characterised repression as both a cause and a result of anxiety.

Freud released his book Hemmung, Symptom und Angst (Inhibition, Symptom and Anxiety) in 1926. It detailed his further developed understanding of neurosis and anxiety. (The book was published in English as The Problem of Anxiety in 1936.) This book expressed his new view that anxiety created repression, rather than the other way around.[49]

Freud also published the book Die Frage der Laienanalyse (The Question of Lay Analysis) in 1926, in which he endorsed non-doctors performing psychoanalysis.

In 1929, Austrian psychiatrist Alfred Adler published the book Problems of Neurosis: A Book of Case-Histories, furthering the school of individual psychology he had established in 1912.

Walter Bradford Cannon's 1932 book The Wisdom of the Body[50] popularised the concept of fight-or-flight.

The American Medical Association released its Standard Classified Nomenclature of Diseases in 1933, the first widely accepted such nomenclature in the United States. By the second edition of 1935, its category of "psychoneuroses" included:

- Hysteria

- Anxiety hysteria

- Conversion hysteria

- Anesthenic type

- Paralytic type

- Hyperkinetic type

- Paresthetic type

- Autonomic type

- Amnesic type

- Mixed hysterical psychoneurosis

- Psychasthenia or compulsive states

- Obsession

- Compulsive tics or spasms

- Phobia

- Mixed compulsive states

- Neurasthenia

- Hypochondriasis

- Reactive depression

- Anxiety state

- Mixed psychoneurosis[51]

The general adaptation syndrome (GAS) theory of stress was developed by Austro-Hungarian physiologist Hans Selye in 1936.[52]

In 1937, Austrian-American psychiatrist Adolph Stern proposed that there were many people with conditions that fitted between the definitions of psychoneurosis and psychosis, and called them the "border line group of neuroses".[53] This group would later become known as borderline personality disorder.

By 1937, the concept of "occupational neuroses" was known by many American health practitioners. It referred to neuroses caused by any aspect of someone's employment.[54]

1939-1952

Followers of Freud's psychoanalytic thinking, such as Carl Jung, Karen Horney, and Jacques Lacan, continued to discuss the concept of neurosis after Freud's death in 1939. The term continues to be used in the Freudian sense in psychology and philosophy.[55][56]

By 1939, some 120,000 British ex-servicemen had received final awards for primary psychiatric disability or were still drawing pensions – about 15% of all pensioned disabilities – and another 44,000 or so were getting pensions for "soldier's heart" or effort syndrome. British historian Ben Shephard notes, "There is, though, much that statistics do not show, because in terms of psychiatric effects, pensioners were just the tip of a huge iceberg."[57]

Approximately 20% of U.S. troops displayed symptoms of combat stress reaction during WWII (1939-1945). It was assumed to be a temporary response of healthy individuals to witnessing or experiencing traumatic events. Symptoms included depression, anxiety, withdrawal, confusion, paranoia, and sympathetic hyperactivity.[58] Thomas W. Salmon's battle neurosis principles were adopted by the U.S. forces during this conflict.[59]

The American Journal of Psychoanalysis was founded by Karen Horney in 1941.[60]

1942 saw American psychologist Carl Rogers publish the handbook Counseling and Psychotherapy, which established his school of person-centered therapy.

Austrian psychiatrist Otto Fenichel's encyclopaedic textbook The psychoanalytic theory of neurosis (1945) set the post-war Freudian orthodoxy on the subject. It has been heavily cited by academic papers in the years since.

Karen Horney's Our Inner Conflicts: A Constructive Theory of Neurosis (1945) was a popular book on the topic.

The post-World War II boom in the number of patient-treating psychologists in the United States led to a major restructure of the American Psychological Association in 1945. Carol Rogers became its president in 1947.[61]

Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl's best selling book Man's Search for Meaning (1946) launched the psychotherapy school of logotherapy.

For his 1947 book, Dimensions of Personality, German-British psychologist Hans Eysenck created the term "neuroticism" to refer to someone whose "constitution may leave them liable to break down [emotionally] with the slightest provocation".[62] The book outlines a two-factor theory of personality, with neuroticism as one of those two factors. This book would be greatly influential on future personality theory.

Karen Horney's Neurosis and Human Growth (1950) further expanded the understanding of neuroses.

French-Swiss psychologist Germaine Guex's 1950 book La névrose d'abandon proposed the existence of the condition of "abandonment neurosis". It also detailed all the forms of treatment Geux had found effective in treating it. (It was published in English as The Abandonment Neurosis in 2015).[63]

In October 1951, the now highly influential Carl Rogers presented a paper in which he described the relationship between neurosis and his understanding of effective therapy. He wrote:

The emotionally maladjusted person, the "neurotic", is in difficulty first because communication within himself has broken down, and second because as a result of this his communication with others has been damaged. If this sounds somewhat strange, then let me put it in other terms. In the "neurotic" individual, parts of himself which have been termed unconscious, or repressed, or denied to awareness, become blocked off so that they no longer communicate themselves to the conscious or managing part of himself... The task of psychotherapy is to help the person achieve, through a special relationship with the therapist, good communication within himself.[64]

The North American Society of Adlerian Psychology was established in 1952,[65] becoming the predominant society of its cause in the world.

DSM-I (1952-1968)

The first edition of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-I) in 1952 included a category named "Psychoneurotic Disorders".[66]

Regarding the definition of this category, the Manual stated:

Grouped as Psychoneurotic Disorders are those disturbances in which "anxiety" is a chief characteristic, directly felt and expressed, or automatically controlled by such defenses as depression, conversion, dissociation, displacement, phobia formation, or repetitive thoughts and acts. For this nomenclature, a psychoneurotic reaction may be defined as one in which the personality, in its struggle for adjustment to internal and external stresses, utilizes the mechanisms listed above to handle the anxiety created. The qualifying phrase, x.2 with neurotic reaction, may be used to amplify the diagnosis when, in the presence of another psychiatric disturbance, a symptomatic clinical picture appears which might be diagnosed under Psychoneurotic Disorders in this nomenclature. A specific example may be seen in an episode of acute anxiety occurring in a homosexual.[66]

Conditions in the category included:

- Anxiety reaction

- Dissociative reaction

- Conversion reaction

- Phobic reaction

- Obsessive compulsive reaction

- Depressive reaction

- Psychoneurotic reaction, other[66]

The DSM-I also included a category of "transient situational personality disorders". This included the diagnosis of "gross stress reaction".[67] This was defined as a normal personality using established patterns of reaction to deal with overwhelming fear as a response to conditions of great stress.[68] The diagnosis included language which relates the condition to combat as well as to "civilian catastrophe".[68] The other situational disorders were "adult situational reaction" and a variety of time-of-life delineated "adjustment reactions". These referred to short-term reactions to stressors.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) were developed for the treatment of neurosis and other conditions from the early 1950s. Because of their undesirable adverse-effect profile and high potential for toxicity, their use was limited.[69][70]

The use of modern exposure therapy for neuroses began in the 1950s in South Africa.[71] South African-American Joseph Wolpe was one of the first psychiatrists to spark interest in treating psychiatric problems as behavioral issues.

In May 1950, pharmacologist Frank Berger (Czech-American) and chemist Bernard John Ludwig engineered meprobamate to be a non-drowsy tranquiliser.[72] Launched as "Miltown" in 1955, it rapidly became the first blockbuster psychotropic drug in American history, becoming popular in Hollywood and gaining fame for its effects.[73] It is highly addictive.

The Meaning of Anxiety was a book released by American psychiatrist Rollo May in 1950.[74] It reviewed the existing research on the subject. It found that some anxiety was a simple reaction to related stimuli, while other anxiety had a more complicated and neurotic beginning. A revised edition of the book was published in 1977.

After the Korean War (1950-1953), Thomas W. Salmon's battle neurosis treatment practices became summarised as the PIE principles:[75]

- Proximity – treat the casualties close to the front and within sound of the fighting.

- Immediacy – treat them without delay and not wait until the wounded were all dealt with.

- Expectancy – ensure that everyone had the expectation of their return to the front after a rest and replenishment.

The Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale was created by American psychologist Janet Taylor in 1953. It measures anxiousness as a personality trait.

The International Association of Analytical Psychology was founded in 1955. It is the predominant organisation devoted to the psychology of Carl Jung.

The American Academy of Psychoanalysis was founded in 1956, for psychiatrists to discuss psychoanalysis in ways that deviated from the orthodoxy of the time.

Also in 1956, American psychologist Albert Ellis published his first paper on his methodology "rational psychotherapy". This and later works defined what is now known as rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT). Ellis believed that people's erroneous beliefs about their adversities was a major cause of neurosis, and his therapy aimed to dissolve these neuroses by correcting people's understandings. Ellis published the first REBT book, How to live with a neurotic, in 1957. Ellis' therapy was also the beginning of what is now called cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Albert Ellis and others founded "The Institute for Rational Living" in April 1959, which later became the Albert Ellis Institute.[76]

The concept of "institutional neurosis" was coined by British psychiatrist Russell Barton,[77] and explained in his well-cited 1959 book Institutional Neurosis.[78] Barton believed that many of the mental health symptoms had by people living in mental hospitals and similar institutions were caused by being in those environments, rather than other causes. Barton was a leader in the deinstitutionalisation movement. (This form of neurosis later came to be known as "institutional syndrome").

Benzodiazepine is a class of highly addictive sedative drugs that reduce anxiety by depressing function in certain parts of the brain. The first of these drugs, chlordiazepoxide (Librium), was made available for sale in 1960. (It was discovered by Polish-American chemist Leo Sternbach in 1955.) Librium was followed with the more popular diazepam (Valium) in 1963.[79] These drugs soon displaced Miltown.[80][81]

Spanish history writer Jose M. Lopez Pinero published Origenes historicos del concepto de neurosis in 1963.[82] It was published in English as Historical Origins of the Concept of Neurosis in 1983.[83]

Neurotics Anonymous began in February 1964, as a twelve-step program to help the neurotic. It was founded in Washington, D.C. by American psychologist Grover Boydston,[84][85] and has since spread through the Americas.

Also in 1964, Polish psychiatrist Kazimierz Dąbrowski released his book Positive Disintegration.[86] The book argues that developing and resolving psychoneurosis is a necessary part of healthy personality development.

The year 1964 also saw the establishment of the American Psychological Association's Division 25, a group of psychologists interested in behaviourism.[87]

The popular textbook The causes and cures of neurosis; an introduction to modern behaviour therapy based on learning theory and the principles of conditioning was published in 1965 by Hans Eysenck and South African-British psychologist Stanley Rachman.[88] It aimed to replace the Freudian approach to neurosis with behaviorism.

The "Hopkins Symptom Checklist" (HSCL) is a self-report symptom inventory that was developed in the mid-1960s from earlier checklists. It measures somatization, obsession-compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, anxiety and depression.[89]

In 1966, psychologists began to observe large numbers of children of Holocaust survivors seeking mental help in clinics in Canada. The grandchildren of Holocaust survivors were overrepresented by 300% among the referrals to psychiatry clinics in comparison with their representation in the general population.[90] Further study lead to the better understanding of transgenerational trauma.

The noted book Psychological stress and the coping process was released by American psychologist Richard Lazarus in 1966.

The well-cited book Anxiety and Behaviour was also released in 1966. As with Eysenck and Rachman's book, it aimed to connect neuroses with behaviourism. It was edited by American psychologist Charles Spielberger.

The Association for Advancement of Behavioral Therapies was founded in 1966. (In 2005, it became the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies.)

DSM-II (1968-1980)

After Freudian thinking became less prominent in psychology, the term "neurosis" came to be used as a near synonym for "anxiety". The second edition of the DSM (DSM-II) in 1968 described neuroses thusly:

Anxiety is the chief characteristic of the neuroses. It may be felt and expressed directly, or it may be controlled unconsciously and automatically by conversion [into physical symptoms], displacement [into mental symptoms] and various other psychological mechanisms. Generally, these mechanisms produce symptoms experienced as subjective distress from which the patient desires relief. The neuroses, as contrasted to the psychoses, manifest neither gross distortion or misinterpretation of external reality, nor gross personality disorganization...

Included in this category were the conditions:

- Hysterical neurosis

- Phobic neurosis

- Obsessive compulsive neurosis

- Depressive neurosis

- Neurasthenic neurosis (neurasthenia)

- Depersonalization neurosis (depersonalization syndrome)

- Hypochondriacal neurosis

- Other neurosis

- Unspecified neurosis

What was previously "gross stress reaction" and "adult situational reaction" was combined into the new "adjustment disorder of adult life", a condition covering mild to strong reactions.[91] Other adjustment disorders for other times-of-life were also included. (Also, the category "transient situational personality disorders" was renamed "transient situational disturbances.")

Anxiety and Neurosis was a popular mass-market book released in 1968 by British psychologist Charles Rycroft.[92]

Neuroses and Personality Disorders was a popular textbook released by American psychologist Elton B McNeil[93] in 1970.[94]

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) was developed by Charles Spielberger and others, and first published in 1970. It provides separate "state" and "trait" measures of a person's anxiety. A revised form was released in 1983.[95]

The book Primal Scream. Primal Therapy: The Cure for Neurosis by American psychologist Arthur Janov was released in 1970. It established primal therapy as a treatment for neurosis. It is based on the idea that neurosis is caused by the repressed pain of childhood trauma. Janov argued that repressed pain can be sequentially brought to conscious awareness for resolution through re-experiencing specific incidents and fully expressing the resulting pain during therapy. Janov criticizes the talking therapies as they deal primarily with the cerebral cortex and higher-reasoning areas and do not access the source of Pain within the more basic parts of the central nervous system.[96] (A second edition of the book was published in 1999).

Chinese-American psychiatrist William WK Zung[97] released his "Anxiety Status Inventory" (ASI) and patient "Self-rating Anxiety Scale" (SAS) in November 1971.[98]

Dąbrowski expanded on his earlier book with Psychoneurosis Is Not An Illness: Neuroses And Psychoneuroses From The Perspective Of Positive Disintegration in 1972.

Anxiety: Current Trends in Theory and Research is a well-cited series of two books released in 1972, and were edited by Charles Spielberger.

The first tetracyclic anti-depressant (TeCA) maprotiline (Ludiomil) was developed by Ciba,[99] and patented in 1966.[99] It was introduced for medical use in 1974.[99][100] TeCAs mianserin (Tolvon) and amoxapine (Asendin) followed shortly thereafter and mirtazapine (Remeron) being introduced later on.[99][100] TeCAs have now generally been superseded by other medications.[101]

Albert Ellis' work was expanded on by fellow American, psychiatrist Aaron Beck. In 1975, Beck released the greatly influential book Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. Beck's cognitive therapy became popular, soon becoming the most popular form of CBT and often being known by that name.

American psychologist Martin Seligman released his highly cited book Helplessness: On Depression, Development and Death in 1975.

Also in 1975, Americans the nurse Ann Burgess and sociologist Lynda Lytle Holmstrom[102] defined rape trauma syndrome in order to draw attention to the striking similarities between the experiences of soldiers returning from war and of rape victims.[103]

Beta-blockers are a class of medication that block the receptor sites for epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline) on beta receptors, of the sympathetic nervous system, which mediates the fight-or-flight response.[104][105] By the mid-1970s, beta blockers were used to reduce symptoms of anxiety. (Scottish pharmacologist James Black had synthesized the first clinically significant beta blockers (propranolol and pronethalol) in 1964).[106]

In 1977, benzodiazepines had become the most prescribed medications globally.[107][108] That was the year the highly addictive benzodiazepine lorazepam (Ativan) entered the US market, (having earlier been invented by American chemist Stanley C Bell in 1963.)[109][110][111]

American psychiatrist and historian Kenneth Levin's Freud's early psychology of the neuroses: a historical perspective was published in 1978.

The well-cited book Cognitive therapy of depression was written by Aaron Beck, American psychiatrist A. John Rush, Canadian psychologist Brian F. Shaw[112] and American psychologist Gary Emery.[113] It was released in 1979. It launched the Beck's cognitive triad explanation of depression, and lead to CBT becoming the main talking-therapy used to treat depression.

In 1979, American biologist Jon Kabat-Zinn founded the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program at the University of Massachusetts to treat the chronically ill.[web 1] This program sparked the application of mindfulness ideas and practices in western medicine.[114]

American-Israeli medical sociologist Aaron Antonovsky in his 1979 book Stress, Health and Coping, stated that an event will not be perceived as stressful when it is appraised as consistent, under some personal control of the outcome, and balanced between underload and overload. Someone resistant to stress will see potential stressors as instead being "meaningful, predictable, and ordered."[115] Antonovsky proposed that stress and a lack of an individual's "resistance resources" (to stressors) may be the main underlying causes of illness and disease, not just mental neuroses. This book established the field of salutogenesis.

In January 1980, Stanley Rachman published a well-cited working definition of "emotional processing",[116] aiming to define the "certain psychological experiences" Freud had mentioned in his 1923 book (and had earlier referred to). It included lists of things likely to improve or retard such processing.

DSM-III (1980-1994)

The DSM replaced its "neurosis" category with an "anxiety disorders" category in 1980, with the release of the DSM-III. It did this because of a decision by its editors to provide descriptions of behavior rather than descriptions of hidden psychological mechanisms.[117] This change was controversial.[118]

This edition of the book also included a condition named "post-traumatic stress disorder" for the first time.[119] This was similar in definition to the "gross stress reaction" of the DSM-I.

The anxiety disorders were defined as:

- Phobic disorders (or phobic neuroses)

- Agoraphobia with panic attacks

- Agoraphobia without panic attacks

- Social phobia

- Simple phobia

- Anxiety states (or anxiety neuroses)

- Panic disorder

- Generalised anxiety disorder

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (or obsessive compulsive neuroses)

- Post-traumatic stress disorder, acute

- Post-traumatic stress disorder, chronic or delayed

- Atypical anxiety disorder

Adjustment disorder remained, and was defined separately. Its time-of-life based subtypes were abolished, replaced with combinations with co-morbid syndromes (such as "Adjustment Disorder with Depressed Mood" and "Adjustment Disorder with Anxious Mood").[119] Adjustment disorder returned to being a short-term condition.

Somatoform disorders, disassociation, depression and hypochondria (all previously considered neuroses) were also treated separately. Neurasthenia (a neurosis that caused otherwise unexplainable fatigue) was loosely mapped to a mild form of depression.

The American "National Membership Committee on Psychoanalysis in Clinical Social Work" was established in May 1980.[120] (It became the "American Association for Psychoanalysis in Clinical Social Work" in 2007).[120]

The Phobia Society of America was founded by psychologist Jerilyn Ross and others in December 1980.[118]

In 1981, American psychologists Christina Maslach and Susan E. Jackson published an instrument for assessing occupational burnout, the Maslach Burnout Inventory.[121] The two researchers described burnout in terms of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (feeling low empathy towards other people in an occupational setting), and reduced feelings of work-related personal accomplishment.[122][123]

The highly addictive benzodiazepine alprazolam (Xanax) was approved for medical use in the United States in 1981,[124][125] (having been invented by American chemist Jackson Hester in 1971.)[126] This and accounts of Valium addiction issues (particularly that of Barbara Gordon) led to the latter no longer being the most prescribed drug in the United States in 1982.[80]

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) was started by American psychologist Steven C. Hayes in around 1982.[127] The core conception of ACT is that psychological suffering is usually caused by experiential avoidance, cognitive entanglement, and resulting psychological rigidity that leads to a failure to take needed behavioral steps in accord with core values. ACT teaches people to "just notice" their unhelpful thoughts and feelings rather than reifying them (mindfulness), to discover their values, and then commit to actions in line with those values.

By 1982, the US military had moved from using the PIE principles to treat wartime stress reactions, and was using the similar "BICEP" instead. This stands for Brevity, Immediacy, Centrality (Marines) or Contact (Army), Expectancy and Proximity. "Brevity" was the aim to treat combatants for only 1 to 4 days. "Centrality" refers to the centralised location of treatment. "Contact" meant a continued contact with their unit and chain of command, "The Soldier must be encouraged to continue to think of himself as a warfighter, rather than a patient or a sick person."[128]

The concept of motivational interviewing was first published about in April 1983 by its originator, the American psychologist William Richard Miller.[129] It is a form of talking treatment that focuses on motivating the patient to do what they believe they need to do.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale was released in June 1983,[130] in a well-cited paper by British psychiatrists Anthony S Zigmond and R Phillip Snaith.[131] The Perceived Stress Scale originates from December 1983,[132] when it was detailed in a paper by American psychologists Sheldon Cohen, Tom Kamarck,[133] and Robin Mermelstein.[134]

American psychiatrist George F. Drinka released the history book Birth of Neurosis: Myth, Malady, and the Victorians in 1984.[135]

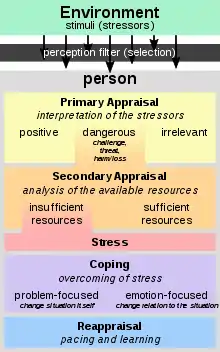

In the 1984 book Stress, Appraisal and Coping, American psychologists Richard Lazarus and Susan Folkman suggested that stress can be thought of as resulting from an "imbalance between demands and resources" or as occurring when "pressure exceeds one's perceived ability to cope".[136] They developed the transactional model of stress. The book is the 17th most cited book in social science.[137][138]

The Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (STSS) was founded in the United States in March 1985 for professionals to share information about the effects of trauma. It later became the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS).

Stress inoculation training was developed to reduce anxiety in doctors during times of intense stress by American doctor Donald Meichenbaum in 1985.[139]

1985 also saw the publishing of the well-cited Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A Cognitive Perspective by Aaron Beck and others.

In 1986, "emotional processing theory" was first presented by psychologists Edna Foa (Israeli-American) and Michael J Kozak[39] (American).[140][56][55] This led to their development of prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. It is characterized by two main treatment procedures. "Imaginal exposure" is repeated purposeful retelling of the trauma memory. "In vivo exposure" is gradually confronting situations, places, and things that are reminders of the trauma or feel dangerous (despite being objectively safe).

The first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medication went on the market in Belgium in 1986. They became available in the United States in 1988, and in other places around this time. This class of drugs largely replaced MOAIs and TCAs, as they were much safer. In the United States, these drugs are most commonly known as Prozac, Zoloft, Paxil, Luvox, Celexa and Lexapro. (The first SSRI was developed by chemists including the Scottish-American Bryan Molloy and Chinese-American David T Wong.) The SSRIs were soon supplemented with the similar SNRI class, which includes Effexor. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome is a significant issue with the use of both classes.

Azapirones are a group of drugs that work at the 5‐HT1A serotonin receptor, and are used to reduce anxiety. The first available azapirone buspirone (Buspar), was approved in the United States in 1986. (It was invented by a team at Mead Johnson in the US in 1968). The only other drug in this class that is widely used in tandospirone (Sediel), which is available in some Asian countries.

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is a form of exposure therapy devised by American psychologist Francine Shapiro from 1987, with the first papers on it published in 1989.[141] It involves focusing on traumatic memories while engaging in side-to-side eye movements or other similar distractions. (The technique became more broadly known after the release of Shapiro's book Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing: Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures in 2001.)

In well-cited paper "Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms", British psychiatrist Michael Rutter in July 1987 found that resilience could be improved in an individual by the 1) reduction of risk impact, 2) reduction of negative chain reactions, 3) establishment and maintenance of self-esteem and self-efficacy, and 4) opening up of opportunities.[142]

Cognitive processing therapy (CPT) was developed by American psychologist Patricia Resick from 1988. The primary focus of the treatment is to help the client understand and reconceptualize their traumatic event in a way that reduces its ongoing negative effects on their current life. Decreasing avoidance of the trauma is crucial to this, since it is necessary for the client to examine and evaluate their meta-emotions and beliefs generated by the trauma.

In 1988, the First European Conference on Traumatic Stress Studies was held in Lincoln, with the participation of the STSS. The European Trauma Network was formed at this time. This became the European Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ESTSS) in 1993.[143]

The highly cited book Anxiety and its Disorders is a wide-ranging review of the subject released by American psychologist David H. Barlow in 1988. A second edition was published in 2002.

The "Penn State Worry Questionnaire" was developed in 1988 by American psychologists Thomas D Borkovec and Andrew M Mathews.[144] A subsequent validation of it has been highly cited.[144]

The Beck Anxiety Inventory was first released in December 1988, by Aaron Beck and others.[145][146]

The conservation of resources (COR) theory of stress was proposed by American psychologist Stevan Hobfoll[147] in March 1989. It is a heavily cited theory that describes the motivation that drives humans to both maintain their current resources and to pursue new resources.[148]

The well cited-paper "Childhood trauma in borderline personality disorder" was released in April 1989, positing "a strong association between a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder and a history of abuse in childhood."[149] It was authored by psychiatrists Judith Lewis Herman (American), John Christopher Perry (Canadian) and Bessel van der Kolk (Dutch-American).

The world's main psychoanalysis bodies decided to admit people who were not medical doctors in 1989, after a major lawsuit was made against them.[150]

In 1990, the Phobia Society of America became the Anxiety Disorders Association of America.[151]

The Anxiety and Phobia Workbook was first released in August 1990. It has since sold over a million copies, and had seven editions. It was written by American philosopher and behavioural scientist Edmund J. Bourne.[152]

The International Karen Horney Society was founded in 1991.[153]

After decades of development, the American psychologist Marsha M. Linehan published a defining paper for a new treatment for borderline personality disorder, called dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) in December 1991.[154] This has come to be used to treat emotional dysregulation more broadly.

The highly-cited August 1991 book Motivational Interviewing by William Richard Miller and South African-British psychologist Stephen Rollnick greatly developed and promoted its subject. Further editions were released in 2002 and 2012.

After decades of development, the American psychologist Marsha M. Linehan published a defining paper for a new treatment for borderline personality disorder, called dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) in December 1991.[155] This has come to be used to treat emotional dysregulation more broadly.

The World Association of Psychoanalysis was founded in January 1992, and became the largest organisation devoted to the psychotherapy of Jacques Lacan.

The first World Conference on Traumatic Stress was held in Amsterdam in June 1992, organised by the ISTSS.[143]

The well-cited book Anxiety: A cognitive perspective was released by British psychologist Michael Eysenck in 1992.

Judith Lewis Herman's 1992 book Trauma and Recovery proposed that there is an important difference between single-incident traumas (Type I traumas), and complex or repeated traumas (Type II).[156] (The sustained negative effect of the latter was later recognised as complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) by the ICD-11.) A second edition of the book was published in 1997.

The well-cited paper "Lifetime and 12-Month Prevalence of DSM-III-R Psychiatric Disorders in the United States: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey" was released by American sociologist Ronald C. Kessler and seven others in January 1994.[157]

DSM-IV (1994-2013)

The conditions acute stress reaction and acute stress disorder were added to the DSM-IV (1994), describing what had previously been considered some types of adjustment disorder. "Acute stress reaction" referred to the symptoms experienced immediately to 48 hours after exposure to a traumatic event. "Acute stress disorder" was defined by symptoms experienced 48 hours to one month following the event. Symptoms experienced for longer than one month were considered to be PTSD.[58]

The "anxiety disorders" were:

- Panic attack

- Agoraphobia

- Panic disorder without agoraphobia

- Panic disorder with agoraphobia

- Agoraphobia without history of panic disorder

- Specific phobia (formerly simple phobia)

- Social phobia (social anxiety disorder)

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder

- Posttraumatic stress disorder

- Acute stress disorder

- Generalised anxiety disorder (includes overanxious disorder of childhood)

- Anxiety disorder due to a general medical condition

- Substance-induced anxiety disorder

- Anxiety disorder not otherwise specified

"Adjustment disorder" remained in the DSM, and was largely unchanged.

The Anxiety Disorders Association of Victoria was established in Melbourne in 1994.[158]

Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) was developed by American psychiatrists Anthony Mannarino,[159] Judith Cohen,[160] and Esther Deblinger[161] in the mid-1990s to help children and adolescents with PTSD. There are 3 treatment phases: stabilization, trauma narration and processing, and integration and consolidation.

The "Depression Anxiety Stress Scales"[162] (DASS) were developed by Australian father-and-son psychologists Syd H Lovibond[163] and Peter F Lovibond,[164] and first made public in 1995.[165] The scales are a self-report instrument designed to measure depression, anxiety and stress; and have become one of the most widely used for these purposes. Both the 42 and 21 question versions were the subject of a highly cited review in 1998.[166] They have been found to correlate highly with Beck's depression and anxiety scales.

Australia's "National Centre for War-Related PTSD" was founded in 1995. In 2000 it broadened its focus to include all post-traumatic mental health, and become "Phoenix Australia – Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health" in 2015.[167]

"Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey" is a highly cited paper published in December 1995 by Ronald C. Kessler and others.[168]

The popular book Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society was edited by Bessel van der Kolk, Australian psychiatrist Alexander C. McFarlane[169] and Norwegian psychiatrist Lars Weisaeth. It was released in 1996.

The dual representation theory (DRT) of PTSD was developed by British psychologists Chris Brewin,[170] Tim Dalgleish,[171] and Stephen Joseph[172] in July 1996.[173] It proposes that certain symptoms of PTSD - such as nightmares, flashbacks, and emotional disturbance - may be attributed to memory processes that occur after exposure to a traumatic event. DRT proposes the existence of two separate memory systems that run in parallel during memory formation: the verbally accessible memory system (VAM) and situationally accessible memory system (SAM).[174]

The World Association for Person Centered & Experiential Psychotherapy & Counseling (WAPCEPC) was established in July 1996,[175] furthering the work of Carl Rogers.

The Deutschsprachige Gesellschaft für Psychotraumatologie[176] (German-speaking Society for Psychotraumatology) was established in 1998. It was co-founded by German psychologist Andreas Maercker.

"Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma" was a highly cited paper published in July 1998 by Israeli-American sociologist Naomi Breslau, Ronald C. Kessler and others.[177]

Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control is an extremely well-cited book published by Canadian-American psychologist Albert Bandura in February 1997. It describes the power of a person's belief in their ability to achieve their goals (dubbed "self-efficacy"), and the effect of this on anxiety, phobias, depression and other things.

Edna Foa and EA Meadows published the well-cited paper "Psychosocial Treatments for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Critical Review" in February 1997.[178] It examined CBT, EMDR and stress inoculation training; and treatment programs that combined these.

Foa's "Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale" was first published in December 1997 in a well-cited paper.[179]

"The development of anxiety: The role of control in the early environment."[180] is a well-cited paper from July 1998, by American psychologists Bruce Chorpita and David H Barlow. It posited that people who feel a lack of control of their lives as a child, are often anxious as adults.

Bestselling book Change Your Brain, Change Your Life: The Breakthrough Program for Conquering Anxiety, Depression, Obsessiveness, Anger, and Impulsiveness was released by American psychiatrist Daniel G. Amen in December 1998.

The well-cited book Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experimental Approach to Behaviour Change was published by American psychologists Steven C. Hayes, Kirk Stroshal[181] and Kelly G. Wilson[182] in 1999. This greatly publicised ACT. A second edition of the book was published in 2016.

Anxiety Canada was established in 1999.[183]

In April 2000, the paper "A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder" was published by psychologists Anke Ehlers (German-British) and David M. Clark (British).[184] They and others followed this with a publishing of a treatment method based on this model in 2005.[185] The three components of this are to: modify negative appraisals of the trauma; reduce re-experiencing symptoms by discussing trauma memories and learning how to differentiate between types of trauma triggers; and reduce behaviors and thoughts that contribute to the maintenance of the "sense of current threat".

The highly cited paper "Posttraumatic stress disorder: the burden to the individual and to society" was published by Ronald C. Kessler in May 2000.[186]

The job demands-resources model (JD-R model) of stress was first described in June 2001 by psychologists Evangelia Demerouti[187] (Greek), Arnold Bakker (Dutch) and others. It suggests strain is a response to imbalance between demands on the individual and the resources they have to deal with those demands.[188][189]

The 9-question Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a diagnostic tool introduced in 2001 to screen adult patients in a primary care setting for the presence and severity of depression.[190][191][192] The PHQ-9 takes less than 3 minutes to complete and simply scores each of the 9 DSM-IV criteria for depression based on the mood module from the original PRIME-MD.[193] Primary care providers frequently use the PHQ-9 to screen for depression in patients.

The well-cited paper "Fears, phobias and preparedness: Toward an evolved module of fear and fear learning"[194] was published in July 2001. It was authored by psychologists Arne Öhman (Swedish) and Susan Mineka[195] (American). It argued that fears are developed by the amygdala and related neural circuitry in an unconscious way, and "is relatively impenetrable to cognitive control." The triggers for such fears are "stimuli that are fear relevant in an evolutionary perspective."

The paper "Traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: prevalence, risk factors and comorbidity" was published by German psychologist Axel Perkonigg,[196] Ronald C. Kessler, S. Storz and German psychologist Hans-Ulrich Wittchen in December 2001.[197]

Another highly cited paper, titled "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder," was published by American psychiatrist Rachel Yehuda in January 2002.[198]

The PTSD Workbook: Simple, Effective Techniques for Overcoming Traumatic Stress Symptoms[199] by American social worker Mary Beth Williams[200] and Finnish psychologist Soili Poijula[201] in March 2002. New editions were released in 2013 and 2016. It has been widely used.

"Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis."[202] is a well-cited paper published in January 2003 by American psychologists Emily J Ozer,[203] Susan R Best, Tami L Lipsey, and Daniel S Weiss.[204] It found that "peritraumatic psychological processes, not prior characteristics, are the strongest predictors of PTSD."

The highly cited paper "Psychological theories of posttraumatic stress disorder" was published by British psychologists Chris Brewin[170] and Emily A Holmes in May 2003. It reviewed Foa's emotional processing theory, Brewin's dual representation theory, and Ehlers and Clark's cognitive theory; and found them to significantly overlap.[205]

The Connor‐Davidson Resilience Scale was first released by American psychiatrists Kathryn M. Connor[206] and Jonathan R.T. Davidson[207] in September 2003.[208]

The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life is a well-cited book by American neuroscientist Joseph E. LeDoux from November 2004. It states that conditions like phobias and PTSD involve malfunctions in the way the brain's emotion systems learn and remember, and details how those systems work. He posits that trauma-initiated conditions occur because the brain's "lower" amygdala-based unconscious fear system is detached from its "higher" cortical and conscious fear system.

In 2005, the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare adopted into that country's variation of the ICD a refined conceptualisation of severe burnout it described as "exhaustion disorder."[209]

The Association for Contextual Behavioral Science was established in 2005, becoming the world's dominant ACT body.

The UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence released a PTSD guideline document in 2005.[210] It received a major update in December 2018.[210]

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) is a generalised anxiety disorder measurement instrument released in May 2006, by its American authors the psychiatrists Robert L. Spitzer and Kurt Kroenke,[211] social worker Janet B. W. Williams, and others.[212] Spitzer and Williams were married.

The PTSD Association of Canada was founded in 2006.[213]

The American Psychiatric Association's Division 56, Division of Trauma Psychology,[214] was founded in 2006 to increase discussion of trauma psychology by American psychiatrists. By 2009, it had more than 1200 members.[215]

"Functional Neuroimaging of Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Processing in PTSD, Social Anxiety Disorder, and Specific Phobia" was a well-cited paper of October 2007. It was authored by American neuroscientists Amit Etkin[216] and Tor Wager. It found that "patients with any of the three disorders consistently showed greater activity than matched comparison subjects in the amygdala and insula..."[217]

"Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies" was a February 2011 paper that was highly cited.[218] Its lead author was British psychiatrist Alex J Mitchell.[219]

In 2012, the Anxiety Disorders Association of America became the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

The October 2012 book Brief Interventions for Radical Change[220] established "Focused Acceptance and Commitment Therapy" (FACT), a short-duration form of ACT. The book was written by American husband-and-wife psychologists Kirk Stroshal and Patricia Robinson,[221] and Swedish psychologist Thomas Gustavsson.[222]

Monkey Mind: A Memoir of Anxiety was a popular book released by American journalist Daniel B Smith in July 2012.

DSM-5 (2013-current)

In 2013, the DSM-5 was released, separating out the "trauma and stress-related disorders" (Freud's etiology for neuroses) from the "anxiety disorders". The former category includes:

- Reactive attachment disorder

- Disinhibited social engagement disorder

- Posttraumatic stress disorder

- Acute stress disorder

- Adjustment disorders

- Other specified trauma- and stressor-related disorder

- Adjustment-like disorders with a late onset

- Ataque de nervios

- Dhat syndrome

- Khyâl cap

- Kufungisisa

- Maladi moun

- Nervios

- Shenjing shuairuo

- Susto

- Taijin kyofusho

- Persistent complex bereavement disorder

- Unspecified trauma- and stressor-related disorder

The popular book My Age of Anxiety: Fear, Hope, Dread, and the Search for Peace of Mind was released in January 2014 by American journalist Scott Stossel.

In September 2014, the bestselling book The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma was released by Bessel van der Kolk. It explained the author's experiences of psychological trauma, and its consequent effects on mental and physical health.[223][224]

"Pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders in adults," was a well-cited paper released in November 2014.[225] It found that there were no effective pharmaceuticals for the conditions. The lead author was German psychologist Maria Kleinstäuber.[226]

The Evil Hours: A Biography of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder was a popular book released by American writer and PTSD-sufferer David J Morris in January 2015.

Another popular book published that month was Rewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and Worry by Americans Catherine M. Pittman[227] (psychologist) and Elizabeth M. Karle[228] (author).

The afflicted support charity PTSD UK was established in 2015.[229]

Declutter Your Mind: How to Stop Worrying, Relieve Anxiety, and Eliminate Negative Thinking is a popular book released in August 2016 by Americans S.J. Scott[230] (psychologist) and Barrie Davenport (coach).

The popular book First, We Make the Beast Beautiful: A New Story About Anxiety was released by Australian journalist Sarah Wilson in February 2017.

The American Psychological Association released its Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults in February 2017.[231] The United States Department of Veterans Affairs released a major update of its Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of PTSD in 2017.[232]

The role of diet in psychology gained greater attention in the first two decades of the 2000s, leading to the concept of nutritional psychiatry and the founding of the "Food and Mood Centre" at Deakin University in 2017 by Australian psychiatrist Felice Jacka.[233]

The popular book, Unfuck Your Brain: Using Science to Get Over Anxiety, Depression, Anger, Freak-Outs, and Triggers, was released by American councillor Faith G Harper[234] in October 2017.

The British Psychological Society commissioned the creation of the "Power Threat Meaning Framework"[185] by a committee over five years, with its first major release in January 2018. The framework aims to provide a complete understanding of psychological trauma, and the best way to treat it. Contrary to most psychological approaches, it includes a large focus on the patient's environment.

The Association Française Pierre Janet[235] was publicly inaugurated in March 2018.[236]

The United Kingdom Psychological Trauma Society (UKPTS) of psychological trauma treating professionals was formed in 2018 from the UK Trauma Group, and the British and Irish Chapter of ESTSS.[237]

Popular book Welcome to the United States of Anxiety: Observations from a Reforming Neurotic was released by American writer Jen Lancaster in October 2020.

Another popular book, Unwinding Anxiety: New Science Shows How to Break the Cycles of Worry and Fear to Heal Your Mind, was released by American psychiatrist Judson Brewer in March 2021.

The ICD-11 (first active in January 2022) included a substantial subset of the DSM-V conditions, and also complex post traumatic stress disorder.

Prevention

Stress inoculation training was developed to reduce anxiety in doctors during times of intense stress by Donald Meichenbaum in 1985.[139] It is a combination of techniques including relaxation, negative thought suppression, and real-life exposure to feared situations used in PTSD treatment.[238] The therapy is divided into four phases and is based on the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy.[139] The first phase identifies the individual's specific reaction to stressors and how they manifest into symptoms. The second phase helps teach techniques to regulate these symptoms using relaxation methods. The third phase deals with specific coping strategies and positive cognitions to work through the stressors. Finally, the fourth phase exposes the client to imagined and real-life situations related to the traumatic event.[239] This training helps to shape the response to future triggers to diminish impairment in daily life.

Patients with acute stress disorder have been found to benefit from another type of cognitive behavioral therapy in preventing PTSD, with clinically meaningful outcomes at six-month follow-up consultations. Supportive counseling was outperformed by a regimen of relaxation, cognitive restructuring, imaginal exposure, and in-vivo exposure.[240] Programs based on mindfulness-based stress reduction also seem to be useful at managing stress.[241]

Playing Tetris shortly after a traumatic experience prevents the development of PTSD in some cases.[242]

Stanley Rachman compiled lists of factors that promote or impede "emotional processing" in 1980, the former reducing the development of neurosis, the latter making it more likely.[116]

Aaron Antonovsky stated that a resilient person is more likely to appraise a situation as "meaningful, predictable, and ordered."[115]

Michael Rutter found that resilience could be improved in an individual by the 1) reduction of risk impact, 2) reduction of negative chain reactions, 3) establishment and maintenance of self-esteem and self-efficacy, and 4) opening up of opportunities.[142]

The use of pharmaceuticals to mitigate the consequences of ASD has made some progress. The Alpha-1 blocker Prazosin, which controls sympathetic response, can be administered to patients to help them unwind and enable better sleep.[243] It is unclear how it functions in this situation. Following a traumatic experience, hydrocortisone (cortisol) has demonstrated some promise as an early prophylactic intervention, frequently slowing the onset of PTSD.[244]

In a systematic literature review in 2014, the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU) found that a number of work environment factors could affect the risk of developing exhaustion disorder or depressive symptoms:

- People who experience a work situation with little opportunity to influence, in combination with too high demands, develop more depressive symptoms.

- People who experience a lack of compassionate support in the work environment develop more symptoms of depression and exhaustion disorder than others. Those who experience bullying or conflict in their work develop more depressive symptoms than others, but it is not possible to determine whether there is a corresponding connection for symptoms of exhaustion disorder.

- People who feel that they have urgent work or a work situation where the reward is perceived as small in relation to the effort develops more symptoms of depression and exhaustion disorder than others. This also applies to those who experience insecurity in the employment, for example concerns that the workplace will be closed down.

- In some work environments, people have less trouble. People who experience good opportunities for control in their own work and those who feel that they are treated fairly develop less symptoms of depression and exhaustion disorder than others.

- Women and men with similar working conditions develop symptoms of depression as much as exhaustion disorder.[245]

Etiology

Historic versions of the DSM and ICD

The term "neurosis" is no longer used in a professional diagnostic sense, it having been eliminated from the DSM in 1980 with the publication of DSM III, and having the last remnants of being removed from the ICD with the enacting of the ICD-11 in 2022. (In the ICD-10 it was used in section F48.8 to describe certain minor conditions.)

According to the "anxiety" concept of the term, there were many different neuroses, including:

- obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD)

- obsessive–compulsive personality disorder

- impulse control disorder

- anxiety disorder

- histrionic personality disorder

- dissociative disorder

- a great variety of phobias

According to C. George Boeree, professor emeritus at Shippensburg University, the symptoms of neurosis may involve:[246]

... anxiety, sadness or depression, anger, irritability, mental confusion, low sense of self-worth, etc., behavioral symptoms such as phobic avoidance, vigilance, impulsive and compulsive acts, lethargy, etc., cognitive problems such as unpleasant or disturbing thoughts, repetition of thoughts and obsession, habitual fantasizing, negativity and cynicism, etc. Interpersonally, neurosis involves dependency, aggressiveness, perfectionism, schizoid isolation, socio-culturally inappropriate behaviors, etc.

Psychoanalytic (Freudian) theory

According to psychoanalytic theory, neuroses may be rooted in ego defense mechanisms, though the two concepts are not synonymous. Defense mechanisms are a normal way of developing and maintaining a consistent sense of self (i.e., an ego). However, only those thoughts and behaviors that produce difficulties in one's life should be called neuroses.

A neurotic person experiences emotional distress and unconscious conflict, which are manifested in various physical or mental illnesses; the definitive symptom being anxiety. Neurotic tendencies are common and may manifest themselves as acute or chronic anxiety, depression, OCD, a phobia, or a personality disorder.

Freud's typology of neuroses in "Introduction to Psychoanalysis" (1923) included:

- Psychoneuroses

- Transference neuroses

- Trauma neuroses

- Narcissistic neuroses

- True neuroses

Jungian theory

Carl Jung found his approach particularly effective for patients who are well adjusted by social standards but are troubled by existential questions. Jung claims to have "frequently seen people become neurotic when they content themselves with inadequate or wrong answers to the questions of life".[247]: 140 Accordingly, the majority of his patients "consisted not of believers but of those who had lost their faith".[247]: 140 A contemporary person, according to Jung,

... is blind to the fact that, with all his rationality and efficiency, he is possessed by 'powers' that are beyond his control. His gods and demons have not disappeared at all; they have merely got new names. They keep him on the run with restlessness, vague apprehensions, psychological complications, an insatiable need for pills, alcohol, tobacco, food — and, above all, a large array of neuroses.[248]: 82

Jung found that the unconscious finds expression primarily through an individual's inferior psychological function, whether it is thinking, feeling, sensation, or intuition. The characteristic effects of a neurosis on the dominant and inferior functions are discussed in his Psychological Types. Jung also found collective neuroses in politics: "Our world is, so to speak, dissociated like a neurotic."[248]: 85

Horney's theory

In her final book, Neurosis and Human Growth, Karen Horney lays out a complete theory of the origin and dynamics of neurosis.[249] In her theory, neurosis is a distorted way of looking at the world and at oneself, which is determined by compulsive needs rather than by a genuine interest in the world as it is. Horney proposes that neurosis is transmitted to a child from their early environment and that there are many ways in which this can occur:[249]: 18

When summarized, they all boil down to the fact that the people in the environment are too wrapped up in their own neuroses to be able to love the child, or even to conceive of him as the particular individual he is; their attitudes toward him are determined by their own neurotic needs and responses.

The child's initial reality is then distorted by their parents' needs and pretenses. Growing up with neurotic caretakers, the child quickly becomes insecure and develops basic anxiety. To deal with this anxiety, the child's imagination creates an idealized self-image:[249]: 22

Each person builds up his personal idealized image from the materials of his own special experiences, his earlier fantasies, his particular needs, and also his given faculties. If it were not for the personal character of the image, he would not attain a feeling of identity and unity. He idealizes, to begin with, his particular "solution" of his basic conflict: compliance becomes goodness, love, saintliness; aggressiveness becomes strength, leadership, heroism, omnipotence; aloofness becomes wisdom, self-sufficiency, independence. What—according to his particular solution—appear as shortcomings or flaws are always dimmed out or retouched.

Once they identify themselves with their idealized image, a number of effects follow. They will make claims on others and on life based on the prestige they feel entitled to because of their idealized self-image. They will impose a rigorous set of standards upon themselves in order to try to measure up to that image. They will cultivate pride, and with that will come the vulnerabilities associated with pride that lacks any foundation. Finally, they will despise themselves for all their limitations. Vicious circles will operate to strengthen all of these effects.

Eventually, as they grow to adulthood, a particular "solution" to all the inner conflicts and vulnerabilities will solidify. They will be either:

- expansive, displaying symptoms of narcissism, perfectionism, or vindictiveness.

- self-effacing and compulsively compliant, displaying symptoms of neediness or codependence.

- resigned, displaying schizoid tendencies.

In Horney's view, mild anxiety disorders and full-blown personality disorders all fall under her basic scheme of neurosis as variations in the degree of severity and in the individual dynamics. The opposite of neurosis is a condition Horney calls self-realization, a state of being in which the person responds to the world with the full depth of their spontaneous feelings, rather than with anxiety-driven compulsion. Thus, the person grows to actualize their inborn potentialities. Horney compares this process to an acorn that grows and becomes a tree: the acorn has had the potential for a tree inside it all along.

References

- "Neurosis". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. HarperCollins Publishers. 2022. ISBN 978-0-618-82435-9.

- Knoff WF (July 1970). "A history of the concept of neurosis, with a memoir of William Cullen". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 127 (1): 80–84. doi:10.1176/ajp.127.1.80. PMID 4913140.

- Bailey H (1927). Demonstrations of physical signs in clinical surgery (1st ed.). Bristol: J. Wright and Sons. p. 208.