Neubrandenburg

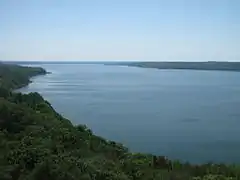

Neubrandenburg (lit. New Brandenburg, IPA: [nɔʏˈbʁandn̩bʊʁk]) is a city in the southeast of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. It is located on the shore of a lake called Tollensesee and forms the urban centre of the Mecklenburg Lakeland.

Neubrandenburg | |

|---|---|

Neubrandenburg skyline with Tollensesee | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Location of Neubrandenburg within Mecklenburgische Seenplatte district  | |

Neubrandenburg  Neubrandenburg | |

| Coordinates: 53°33′25″N 13°15′40″E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Mecklenburg-Vorpommern |

| District | Mecklenburgische Seenplatte |

| Subdivisions | 10 Stadtteile |

| Government | |

| • Lord mayor (2022–29) | Silvio Witt[1] (Ind.) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 85.65 km2 (33.07 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 20 m (70 ft) |

| Population (2021-12-31)[2] | |

| • Total | 63,043 |

| • Density | 740/km2 (1,900/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 17033, 17034, 17036, 17050[3] |

| Dialling codes | 0395 |

| Vehicle registration | NB |

| Website | www.neubrandenburg.de |

The city is famous for its rich medieval heritage of Brick Gothic architecture, including the world's best preserved defensive wall of this style as well as a Concert Church (Saint Mary), the home venue of the Neubrandenburg Philharmonic. It is part of the European Route of Brick Gothic, a route which leads through seven countries along the Baltic Sea coast. Neubrandenburg is nicknamed for its four medieval city gates - "Stadt der Vier Tore" ("City of Four Gates").

Since 2011, Neubrandenburg has been the capital of the Mecklenburgische Seenplatte district. It is the third-largest city and one of the main urban centres of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. The city is an economical node of northeastern Germany, featuring one of the highest national ranks in employment density and GDP per capita.[4] The closest greater urban areas are the regiopolis of Rostock and the metropolises of Szczecin, Berlin and Hamburg. Since 1991, Neubrandenburg has hosted a University of Applied Sciences that offers international exchanges, guest programs and study programs.

History

The first Christian monks in the area were Premonstratensian in Broda Abbey, a monastery at the shore (about 1240). The foundation of the city known as of Neubrandenburg took place in 1248, when the Margrave of Brandenburg decided to build a settlement in the northern part of his fief, naming it after the older city of Brandenburg further south. In 1292, the city and the surrounding area became part of Mecklenburg.

The city flourished as a trade centre until the Thirty Years' War (1618–48), when this position was lost due to incessant warfare. During the dramatic advance of the Swedish army of Gustavus Adolphus into Germany, the city was garrisoned by Swedes, but it was retaken by Imperial Catholic League forces in 1631. During this campaign, it was widely reported that the Catholic forces killed many of the Swedish and Scottish soldiers while they were surrendering. Later, according to the Scottish soldier of fortune Robert Munro, 18th Baron of Foulis, when the Swedes themselves adopted a "no prisoners" policy, they would cut short any pleas for mercy with the cry of "New Brandenburg!". The city, therefore, played an unconscious role in the escalation of brutality of one of history's most brutal wars.

During the Second World War, two German prisoner-of-war camps for Allied POWs of various nationalities were located in Fünfeichen within the city limits: the large Stalag II-A and the adjacent Oflag II-E/67 for officers. The town was also the location of a forced labour camp for Sinti and Romani people.[5] In 1945, few days before the end of the Second World War, 80% of the old town was burned down by the Red Army in a great fire, and about 600 people committed suicide as a result.[6] Since then, most buildings of historical relevance have been rebuilt. After the war, from 1945 to 1948, the special NKVD-camp Nr. 9 was operated at the site of the former Stalag II-A.

Neubrandenburg was a bezirk centre between 1952 and 1990.

Sights and monuments

Neubrandenburg has preserved its medieval city wall in its entirety. The wall, 7 m high with a perimeter of 2.3 km, has four Brick Gothic city gates, dating back to the 14th and 15th centuries. Of these, one of the most impressive is the Stargarder Tor (pictured), with its characteristic gable-like shape and the filigree tracery and rosettes on the outer defence side.

Another place of interest is the Brick Gothic Marienkirche (Church of the Virgin Mary or St. Mary's Church, Konzertkirche), completed 1298. The church was nearly destroyed in 1945, but it was restored in 1975 and now houses a concert hall (opened 2001).

The tallest highrise in the city is the 56m Haus der Kultur und Bildung (HKB, House of Culture & Education), opened in 1965. Its slender appearance has earned it the nickname Kulturfinger ("culture finger").

Other attractions include Neubrandenburg Regional Museum.

St. Mary's Church (used for concerts)

St. Mary's Church (used for concerts) Treptow Gate with Neubrandenburg Regional Museum

Treptow Gate with Neubrandenburg Regional Museum Stargard Gate

Stargard Gate New Gate

New Gate Friedland Gate

Friedland Gate

Belvedere

Belvedere

Education

- Hochschule Neubrandenburg (University of Applied Sciences)

- Three large secondary schools

Sports

Neubrandenburg is known as city of sports (Sportstadt). The city is famous for being home to various Olympic medal winners and talents in sports, especially in canoeing (Andreas Dittmer, Martin Hollstein), discus throwing and shotputting (Astrid Kumbernuss, Ralf Bartels, Franka Dietzsch) and running (Katrin Krabbe). Neubrandenburg was the location of both of the world record throws in Discus, by Jürgen Schult in 1986 and by Gabriele Reinsch in 1988. The Jahnstadion, the Jahnsportforum stadium, the Stadthalle and adjacent sport parks offer vast options for large sport and culture events. The city is also home to a dedicated sports elite school, the Sportgymnasium Neubrandenburg.

Twin towns – sister cities

References

- Kommunalwahlen in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Ergebnisse der Bürgermeisterwahlen, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Landesamt für innere Verwaltung, accessed 7 March 2022.

- "Bevölkerungsstand der Kreise, Ämter und Gemeinden 2021" (XLS) (in German). Statistisches Amt Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. 2022.

- Agentur für Arbeit Neubrandenburg Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Facts & numbers about Neubrandenburg (neubrandenburg.de)

- "Lager für Sinti und Roma Neubrandenburg". Bundesarchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- Lakotta, Beate (2005-03-05). "Tief vergraben, nicht dran rühren" (in German). SPON. Retrieved 2010-08-16.

- "Partnerstädte". neubrandenburg.de (in German). Neubrandenburg. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

Further reading

- Chronicles

- (in German) Gottlob von Hacke: Geschichte der Vorderstadt Neubrandenburg. Vol. I: Vom Jahr 1248 bis 1711 (no further volume did appear). Neubrandenburg 1783 (online)

- (in German) Franz Boll: Chronik der Vorderstadt Neubrandenburg. Neubrandenburg 1875. (Reprinted several times)

- (in German) Wilhelm Ahlers: Historisch-topographische Skizzen aus der Vorzeit der Vorderstadt Neubrandenburg. Neubrandenburg 1876. (Reprinted several times)

- (in German) Karl Wendt: Geschichte der Vorderstadt Neubrandenburg in Einzeldarstellungen. Neubrandenburg 1922. (Reprinted in 1984)

External links

Neubrandenburg travel guide from Wikivoyage

Neubrandenburg travel guide from Wikivoyage- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 423.

- Official website

(in German and English)

(in German and English) - https://www.britannica.com/place/Brandenburg-Germany