New Forest

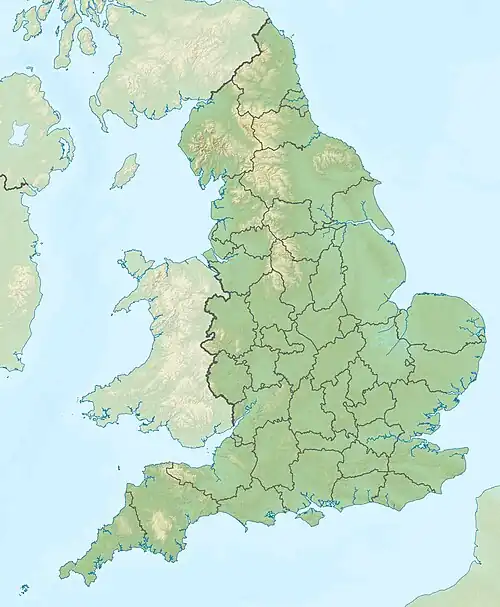

The New Forest is one of the largest remaining tracts of unenclosed pasture land, heathland and forest in Southern England, covering southwest Hampshire and southeast Wiltshire. It was proclaimed a royal forest by William the Conqueror, featuring in the Domesday Book.

| The New Forest National Park[1] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |||||||||||

Beech trees in Mallard Wood, part of the New Forest

| |||||||||||

| Nearest city | Southampton | ||||||||||

| Area | 566 km2 (219 sq mi) National Park New Forest: 380 km2 (150 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Established | 1079 (as Royal Forest), 1 March 2005 (as National Park) | ||||||||||

| Visitors | 14.75 million (est) (in 2009) | ||||||||||

| Governing body | New Forest National Park Authority | ||||||||||

| Website | https://www.newforestnpa.gov.uk/ | ||||||||||

| Official name | The New Forest | ||||||||||

| Designated | 22 September 1993 | ||||||||||

| Reference no. | 622[2] | ||||||||||

| Site of Special Scientific Interest | |

Beaulieu Mill Pond | |

| Location | Hampshire Wiltshire |

|---|---|

| Grid reference | SU 269 072[3] |

| Interest | Biological Geological |

| Area | 28,924.5 hectares (71,474 acres)[3] |

| Notification | 1996[3] |

| Location map | Magic Map |

It is the home of the New Forest Commoners, whose ancient rights of common pasture are still recognised and exercised, enforced by official verderers and agisters. In the 18th century, the New Forest became a source of timber for the Royal Navy. It remains a habitat for many rare birds and mammals.

The boundaries of the forest have varied over time and depend on the purpose of delimiting them.[4] It is a 28,924.5-hectare (71,474-acre) biological and geological Site of Special Scientific Interest.[3][5] Several areas are Geological Conservation Review sites, including Mark Ash Wood,[6] Shepherd’s Gutter,[7] Cranes Moor,[8] Studley Wood,[9] and Wood Green.[10] There are also a number of Nature Conservation Review sites.[11] It is a Special Area of Conservation,[12] a Ramsar site[13][14] and a Special Protection Area.[15][16] Copythorne Common is managed by the Hampshire and Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust,[17] Kingston Great Common is a national nature reserve[18] and New Forest Northern Commons is managed by the National Trust.[19]

The New Forest covers two parliamentary constituencies; New Forest East and New Forest West.

Prehistory

Like much of England, the site of the New Forest was once deciduous woodland, recolonised by birch and eventually beech and oak after the withdrawal of the ice sheets starting around 12,000 years ago. Some areas were cleared for cultivation from the Bronze Age onwards; the poor quality of the soil in the New Forest meant that the cleared areas turned into heathland "waste", which may have been used even then as grazing land for horses.[20]

There was still a significant amount of woodland in this part of Britain, but this was gradually reduced, particularly towards the end of the Middle Iron Age around 250–100 BC, and most importantly the 12th and 13th centuries, and of this essentially all that remains today is the New Forest.[21]

There are around 250 round barrows[22] within its boundaries, and scattered boiling mounds, and it also includes about 150 scheduled monuments.[23] One may be the only known inhumation site of the Early Iron Age and the only known Hallstatt culture burial place in Britain, though any bodies are likely decomposed beyond detection by the acidic soil.[24]

History

Following Anglo-Saxon settlement in Britain, according to Florence of Worcester (d. 1118), the area became the site of the Jutish kingdom of Ytene; this name was the genitive plural of Yt meaning "Jute", i.e. "of the Jutes".[25] The Jutes were one of the early Anglo-Saxon tribal groups who colonised this area of southern Hampshire.

Following the Norman Conquest, the New Forest was proclaimed a royal forest, in about 1079, by William the Conqueror. It was used for royal hunts, mainly of deer.[26] It was created at the expense of more than 20 small hamlets and isolated farmsteads; hence it was then 'new' as a single compact area.[27]

The New Forest was first recorded as Nova Foresta in Domesday Book in 1086, where a section devoted to it is interpolated between lands of the king's thegns and the town of Southampton; it is the only forest that the book describes in detail. Twelfth-century chroniclers alleged that William had created the forest by evicting the inhabitants of 36 parishes, reducing a flourishing district to a wasteland; this account is thought dubious by most historians, as the poor soil in much of the area is believed to have been incapable of supporting large-scale agriculture, and significant areas appear to have always been uninhabited.[28][29]

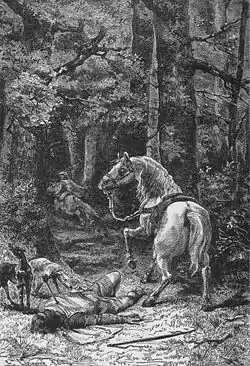

Two of William's sons died in the forest: Prince Richard sometime between 1069 and 1075, and King William II (William Rufus) in 1100. Though many claim the latter is due to an inaccurate arrow shot from his hunting companion, local folklore asserted that this was punishment for the crimes committed by William when he created his New Forest; 17th-century writer Richard Blome provides detail:

In this County [Hantshire] is New-Forest, formerly called Ytene, being about 30 miles in compass; in which said tract William the Conqueror (for the making of the said Forest a harbour for Wild-beasts for his Game) caused 36 Parish Churches, with all the Houses thereto belonging, to be pulled down, and the poor Inhabitants left succourless of house or home. But this wicked act did not long go unpunished, for his Sons felt the smart thereof; Richard being blasted with a pestilent Air; Rufus shot through with an Arrow; and Henry his Grand-child, by Robert his eldest son, as he pursued his Game, was hanged among the boughs, and so dyed. This Forest at present affordeth great variety of Game, where his Majesty oft-times withdraws himself for his divertisement.[30]

The reputed spot of Rufus's death is marked with a stone known as the Rufus Stone. John White, Bishop of Winchester, said of the forest:

From God and Saint King Rufus did Churches take, From Citizens town-court, and mercate place, From Farmer lands: New Forrest for to make, In Beaulew tract, where whiles the King in chase Pursues the hart, just vengeance comes apace, And King pursues. Tirrell him seing not, Unwares him flew with dint of arrow shot.[31]

The common rights were confirmed by statute in 1698. The New Forest became a source of timber for the Royal Navy, and plantations were created in the 18th century for this purpose. During the Great Storm of 1703, about 4,000 oak trees were lost.

The naval plantations encroached on the rights of the Commoners, but the Forest gained new protection under the New Forest Act 1877, which confirmed the historic rights of the Commoners and entrenched that the total of enclosures was henceforth not to exceed 65 km2 (25 sq mi) at any time. It also reconstituted the Court of Verderers as representatives of the Commoners (rather than the Crown).

As of 2005, roughly 90% of the New Forest is still owned by the Crown. The Crown lands have been managed by Forestry England since 1923 and most of the Crown lands now fall inside the new National Park.

Felling of broadleaved trees, and their replacement by conifers, began during the First World War to meet the wartime demand for wood. Further encroachments were made during the Second World War. This process is today being reversed in places, with some plantations being returned to heathland or broadleaved woodland. Rhododendron remains a problem.

During the Second World War, an area of the forest, Ashley Range, was used as a bombing range.[32] During 1941–1945, the Beaulieu, Hampshire Estate of Lord Montagu in the New Forest was the site of group B finishing schools for agents[33] operated by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) between 1941 and 1945. (One of the trainers was Kim Philby who was later found to be part of a spy ring passing information to the Soviets.) In 2005, a special exhibition was mounted at the Estate, with a video showing photographs from that era as well as voice recordings of former SOE trainers and agents.[34][35]

Further New Forest Acts followed in 1949, 1964 and 1970. The New Forest became a Site of Special Scientific Interest in 1971, and was granted special status as the New Forest Heritage Area in 1985, with additional planning controls added in 1992. The New Forest was proposed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in June 1999, but UNESCO did not take up the nomination.[36] It became a National Park on 1 March 2005,[37] transferring a wide variety of planning and control decisions to the New Forest National Park Authority, who work alongside the local authorities, land owners and crown estates in managing the New Forest.[38]

A report in 2023 stated that the region will face hotter, drier summers and wetter winters. In 2019, the carbon dioxide emissions of the New Forest District Council area were recorded as 928,000 tonnes.[39]

Death of William Rufus

Death of William Rufus The Rufus Stone Memorial

The Rufus Stone Memorial WW2 remains at Ibsley

WW2 remains at Ibsley

Common rights

Forest laws were enacted to preserve the New Forest as a location for royal deer hunting, and interference with the king's deer and its forage was punished. The inhabitants of the area (commoners) had pre-existing rights of common: to turn horses and cattle (but only rarely sheep) out into the Forest to graze (common pasture), to gather fuel wood (estovers), to cut peat for fuel (turbary), to dig clay (marl), and to turn out pigs between September and November to eat fallen acorns and beechnuts (pannage or mast). There were also licences granted to gather bracken after Michaelmas Day (29 September) as litter for animals (fern).

Along with grazing, pannage is still an important part of the Forest's ecology. Pigs can eat acorns without problem, but for ponies and cattle, large quantities of acorns can be poisonous. Pannage always lasts at least 60 days, but the start date varies according to the weather – and when the acorns fall. The verderers decide when pannage will start each year. At other times the pigs must be taken in and kept on the owner's land, with the exception that pregnant sows, known as privileged sows, are always allowed out providing they are not a nuisance and return to the Commoner's holding at night (they must not be "levant and couchant" in the Forest, that is, they may not consecutively feed and sleep there). This last is an established practice rather than a formal right.

The principle of levancy and couchancy applies generally to the right of pasture.[40][41] Commoners must have backup land, outside the Forest, to accommodate these depastured animals when necessary, for example during a foot-and-mouth disease epidemic.

Commons rights are attached to particular plots of land (or in the case of turbary, to particular hearths), and different land has different rights – and some of this land is some distance from the Forest itself. Rights to graze ponies and cattle are not for a fixed number of animals, as is often the case on other commons. Instead a "marking fee" is paid for each animal each year by the owner. The marked animal's tail is trimmed by the local agister (verderers' official), with each of the four or five forest agisters using a different trimming pattern. Ponies are branded with the owner's brand mark; cattle may be branded, or nowadays may have the brand mark on an ear tag. Grazing of Commoners' ponies and cattle is an essential part of the management of the forest, helping to maintain the heathland, bog, grassland and wood-pasture habitats and their associated wildlife.

Recently this ancient practice has come under pressure as benefitting houses pass to owners with no interest in commoning. Existing families with a new generation heavily rely on inheritance of, rather than mostly the expensive purchase of, a benefitting house with paddock or farm.

The Verderers and Commoners' Defence Association has fought back against these allied economic threats. The EU Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) helped some Commoners significantly. Commoners marking animals for grazing can claim about £200 per cow per year, and about £160 for a pony, and if participating in the stewardship scheme, more. With 10 cattle and 40 ponies, a Commoner qualifying for both schemes would receive over £8,000 a year, and more if they put out pigs: net of marking fees, feed and veterinary costs this part-time level of involvement across a family is calculated to give annual income in the thousands of pounds in most years. Whether those subsidies will survive Brexit is unclear. The BPS payment is based on the number of animals marked for the Forest, whether or not these are actually turned out. The livestock actually grazing the Forest are therefore considerably fewer than those marked.

Geography

The New Forest National Park area covers 566 km2 (219 sq mi),[42] and the New Forest SSSI covers almost 300 km2 (120 sq mi), making it the largest contiguous area of unsown vegetation in lowland Britain. It includes roughly:

- 146 km2 (56 sq mi) of broadleaved woodland

- 118 km2 (46 sq mi) of heathland and grassland

- 33 km2 (13 sq mi) of wet heathland

- 84 km2 (32 sq mi) of tree plantations (woodland inclosures) established since the 18th century, including 80 km2 (31 sq mi) planted by Forestry England since the 1920s.

The New Forest has also been classed as National Character Area No. 131 by Natural England. The NCA covers an area of 738 km2 (285 sq mi) and is bounded by the Dorset Heaths and Dorset Downs to the west, the West Wiltshire Downs to the north and the South Hampshire Lowlands and South Coast Plain to the east.[43]

The New Forest is drained to the south by three rivers, Lymington River, Beaulieu River and Avon Water, and to the west by the Latchmore Brook, Dockens Water, Linford Brook and other streams.

The highest point in the New Forest is Pipers Wait, near Nomansland. Its summit is 129 metres (423 feet) above sea level.[44][45]

The Geology of the New Forest consists mainly of sedimentary rock, in the centre of a sedimentary basin known as the Hampshire Basin.

Wildlife

The ecological value of the New Forest is enhanced by the relatively large areas of lowland habitats, lost elsewhere, which have survived. There are several kinds of important lowland habitat including valley bogs, alder carr, wet heaths, dry heaths and deciduous woodland. The area contains a profusion of rare wildlife, including the New Forest cicada Cicadetta montana, the only cicada native to Great Britain, although the last unconfirmed sighting was in 2000.[46] The wet heaths are important for rare plants, such as marsh gentian (Gentiana pneumonanthe) and marsh clubmoss (Lycopodiella inundata) and other important species include the wild gladiolus (Gladiolus illyricus).[47]

Several species of sundew are found, as well as many unusual insect species, including the southern damselfly (Coenagrion mercuriale), large marsh grasshopper (Stethophyma grossum) and the mole cricket (Gryllotalpa gryllotalpa), all rare in Britain. In 2009, 500 adult southern damselflies were captured and released in the Venn Ottery nature reserve in Devon, which is owned and managed by the Devon Wildlife Trust.[48] The Forest is an important stronghold for a rich variety of fungi, and although these have been heavily gathered in the past, there are control measures now in place to manage this.

Birds

Specialist heathland birds are widespread, including Dartford warbler (Curruca undata), woodlark (Lullula arborea), northern lapwing (Vanellus vanellus), Eurasian curlew (Numenius arquata), European nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus), Eurasian hobby (Falco subbuteo), European stonechat (Saxicola rubecola), common redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus) and tree pipit (Anthus sylvestris). As in much of Britain common snipe (Gallinago gallinago) and meadow pipit (Anthus trivialis) are common as wintering birds, but in the Forest they still also breed in many of the bogs and heaths respectively.

Woodland birds include wood warbler (Phylloscopus sibilatrix), stock dove (Columba oenas), European honey buzzard (Pernis apivorus) and northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis). Common buzzard (Buteo buteo) is very common and common raven (Corvus corax) is spreading. Birds seen more rarely include red kite (Milvus milvus), wintering great grey shrike (Lanius exubitor) and hen harrier (Circus cyaneus) and migrating ring ouzel (Turdus torquatus) and northern wheatear (Oenanthe oenanthe).

Reptiles and amphibians

All three British native species of snake inhabit the Forest. The adder (Vipera berus) is the most common, being found on open heath and grassland. The grass snake (Natrix natrix) prefers the damper environment of the valley mires. The rare smooth snake (Coronella austriaca) occurs on sandy hillsides with heather and gorse. It was mainly adders which were caught by Brusher Mills (1840–1905), the "New Forest Snake Catcher". He caught many thousands in his lifetime, sending some to London Zoo as food for their animals.[49][50] A pub in Brockenhurst is named The Snakecatcher in his memory. All British snakes are now legally protected, and so the New Forest snakes are no longer caught.

A programme to reintroduce the sand lizard (Lacerta agilis) started in 1989[51] and the great crested newt (Triturus cristatus) already breeds in many locations.

Sand lizards in a captive breeding and reintroduction programme[52] together with adders, grass snakes, smooth snakes, frogs and toads can be seen at The New Forest Reptile Centre about two miles east of Lyndhurst. The centre was established in 1969 by Derek Thomson MBE, a Forestry England keeper, who was also involved in establishing the deer viewing platform at nearby Bolderwood.[53]

Ponies, cattle, donkeys, pigs

Commoners' cattle, ponies and donkeys roam throughout the open heath and much of the woodland, and it is largely their grazing that maintains the open character of the Forest. They are also frequently seen in the Forest villages, where home and shop owners must take care to keep them out of gardens and shops. The New Forest pony is one of the indigenous horse breeds of the British Isles, and is one of the New Forest's most famous attractions – most of the Forest ponies are of this breed, but there are also some Shetlands and their crossbreeds.

Cattle are of various breeds, most commonly Galloways and their crossbreeds, but also various other hardy types such as Highlands, Herefords, Dexters, Kerries and British whites. The pigs used for pannage, during the autumn months, are now of various breeds, but the New Forest was the original home of the Wessex Saddleback, now extinct in Britain.

Deer

Numerous deer live in the Forest; they are usually rather shy and tend to stay out of sight when people are around, but are surprisingly bold at night, even when a car drives past. Fallow deer (Dama dama) are the most common, followed by roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) and red deer (Cervus elaphus). There are also smaller populations of the introduced sika deer (Cervus nippon) and muntjac (Muntiacus reevesii).

Other mammals

The red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) survived in the Forest until the 1970s – longer than most places in lowland Britain (though it still occurs on The Isle of Wight and the nearby Brownsea Island). It is now fully supplanted in the Forest by the introduced North American grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis). The European polecat (Mustela putorius) has recolonised the western edge of the Forest in recent years. European otter (Lutra lutra) occurs along watercourses, as well as the introduced American mink (Neogale vison).

Conservation measures

The New Forest is designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), an EU Special Area of Conservation (SAC),[54] a Special Protection Area for birds (SPA),[55] and a Ramsar Site;[56] it also has its own Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP).[57]

Settlements

The New Forest itself gives its name to the New Forest district of Hampshire, and the National Park area, of which it forms the core.

The Forest itself is dominated by four larger 'defined' villages, Sway, Brockenhurst, Lyndhurst and Ashurst, with several smaller villages such as Burley, Beaulieu, Godshill, Fritham, Nomansland, and Minstead also lying within or immediately adjacent. Outside of the National Park Area in New Forest District, several clusters of larger towns frame the area – Totton and the Waterside settlements (Marchwood, Dibden, Hythe, Fawley) to the East, Christchurch, New Milton, Milford on Sea, and Lymington to the South, and Fordingbridge and Ringwood to the West.

New Forest National Park

Consultations on the possible designation of a National Park in the New Forest were commenced by the Countryside Agency in 1999. An order to create the park was made by the Agency on 24 January 2002 and submitted to the Secretary of State for confirmation in February 2002. Following objections from seven local authorities and others, a public inquiry was held from 8 October 2002 to 10 April 2003, and concluded by endorsing the proposal with some detailed changes to the boundary of the area to be designated.

On 28 June 2004, Rural Affairs Minister Alun Michael confirmed the government's intention to designate the area as a National Park, with further detailed boundary adjustments. The area was formally designated as such on 1 March 2005. A national park authority for the New Forest was established on 1 April 2005 and assumed its full statutory powers on 1 April 2006.[58]

Forestry England retain their powers to manage the Crown land within the Park. The Verderers under the New Forest Acts also retain their responsibilities, and the park authority is expected to co-operate with these bodies, the local authorities, English Nature and other interested parties. The designated area of the National Park covers 566 km2 (219 sq mi)[42] and includes many existing SSSIs. It has a population of about 38,000 (it excludes most of the 170,256 people who live in the New Forest local government district). As well as most of the New Forest district of Hampshire, it takes in the South Hampshire Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, a small corner of Test Valley district around the village of Canada and part of Wiltshire south-east of Redlynch.

The area covered by the park excludes two of the areas initially proposed: most of the valley of the River Avon to the west of the Forest and Dibden Bay to the east. Two challenges were made to the designation order, by Meyrick Estate Management Ltd in relation to the inclusion of Hinton Admiral Park, and by RWE NPower Plc in relation to the inclusion of Fawley Power Station. The second challenge was settled out of court, with the power station being excluded.[59] The High Court upheld the first challenge;[60] but an appeal against the decision was then heard by the Court of Appeal in Autumn 2006. The final ruling, published on 15 February 2007, found in favour of the challenge by Meyrick Estate Management Ltd,[61] and the land at Hinton Admiral Park is therefore excluded from the New Forest National Park. The total area of land initially proposed for inclusion but ultimately left out of the Park is around 120 km2 (46 sq mi).

Visitor attractions and places

Politics

The New Forest is represented by two Members of Parliament; in New Forest East and New Forest West.

Cultural references

There is an allusion to the foundation of the New Forest in an end-rhyming poem found in the Peterborough Chronicle's entry for 1087, The Rime of King William.

The Forest forms a backdrop to numerous books. The Children of the New Forest is a children's novel published in 1847 by Frederick Marryat, set in the time of the English Civil War. Charles Kingsley's A New Forest Ballad (1847) mentions several New Forest locations, including Ocknell Plain, Bradley [Bratley] Water, Burley Walk and Lyndhurst churchyard.[62] Edward Rutherfurd's work of historical fiction, The Forest is based in the New Forest in the period from 1099 to 2000. The Forest is also a setting of the Warriors novel series, in which the 'Forest Territories' was initially based on New Forest.[63]

The New Forest and southeast England, around the 12th century, is a prominent setting in Ken Follett's novel The Pillars of the Earth. It is also a prominent setting in Elizabeth George's novel This Body of Death. Oberon, Titania and the other Shakespearean fairies live in a rapidly diminishing Sherwood Forest whittled away by urban development in the fantasy novel A Midsummer's Nightmare by Garry Kilworth. On Midsummer's Eve, a most auspicious day, the fairies embark on the long journey to the New Forest in Hampshire where the fairies' magic will be restored to its former glory.

Notable residents

- Eric Ashby (1918–2003), naturalist and wildlife cameraman

- Alice Bentinck (born 1986), co-founder and COO of Entrepreneur First, London

- William Arnold Bromfield (1801–1851), English botanist

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1869–1930), author

- Harry Warner Farnall (1838–1891), New Zealand politician

- Gerald Gardner (1884–1964), founder of Gardnerian Wicca

- Pam Gems (1925–2011), English playwright

- Arthur Sumner Gibson (1844–1927), rugby union international

- Edgar Gibson (1848–1924), 31st Bishop of Gloucester

- Clifford Hall (1902–1982), English cricketer

- Frederick Harold (1888–1964), English cricketer

- Gerry Hill (1913–2006), English cricketer

- Ralph Hollins (born 1931), naturalist

- Mark Kermode[64][65] (born 1963), film critic and musician

- Sybil Leek (1917–1982), witch, author, astrologer

- Sir Charles Lyell (1797–1875), Victorian geologist and polymath

- Florence Nightingale (1820–1910), nurse

- Chris Packham (born 1961), naturalist and broadcaster

- Philip Harris (born 1965), artist

References

- "The IUCN categories". National Parks Portal. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

Even though the IUCN call category II 'National Parks', the UK's National Parks are actually in category V.

- "The New Forest". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "Designated Sites View: The New Forest". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- See, for example, this concerning the National Park boundary: "New Forest National Park (2001)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 9 January 2001. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- "Map of The New Forest". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "Mark Ash Wood (Quaternary of South Central England)". Geological Conservation Review. Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Shepherd's Gutter, near Bramshaw (Palaeogene)". Geological Conservation Review. Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Cranes Moor (Quaternary of South Central England)". Geological Conservation Review. Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Studley Wood (Palaeogene)". Geological Conservation Review. Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Wood Green Gravel Pit (Quaternary of South Central England)". Geological Conservation Review. Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Ratcliffe, Derek, ed. (1977). A Nature Conservation Review. Vol. 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 51–52, 120–21, 206–07. ISBN 0521-21403-3.

- "Designated Sites View: New Forest". Special Areas of Conservation. Natural England. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Designated Sites View: Solent and Southampton Water". Ramsar Site. Natural England. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- "Designated Sites View: The New Forest". Ramsar Site. Natural England. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- "Designated Sites View: Solent and Southampton Water". Special Protection Areas. Natural England. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- "Designated Sites View: The New Forest". Special Protection Areas. Natural England. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- "Copythorne Common". Hampshire and Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "Designated Sites View: Kingston Great Common". National Nature Reserves. Natural England. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "New Forest Northern Commons". National Trust. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Cunliffe, Barry, Iron Age Communities in Britain, 2010. pg 428: "One interpretation of this is to suppose that horses were allowed to breed in the wild on the wastelands and were annually rounded up for selection and subsequent training. The proximity of Gussage to the heathlands of the New Forest is suggestive..."

- "New Forest Handbook History of the New Forest Part 1". Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- "Hampshire Treasures". Hants.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- "UNESCO World Heritage". Whc.unesco.org. 21 June 1999. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- Cunliffe, Barry; Iron Age Communities in Britain 2010, pg 544.

- "Old Hampshire Gazetteer (citing Ekwall, 1953: 132)". port.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "History of the New Forest". New Forest National Park. 2009. Archived from the original on 13 October 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- "Old Hampshire Gazetteer (citing Muir, 1981)". port.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- H. C. Darby. Domesday England, pp. 198–199. Cambridge University Press, 1986. ISBN 0-521-31026-1

- Young, Charles R. (1979). The Royal Forests of Medieval England. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0-8122-7760-0.

- Blome, Richard (1673). "Britannia: or, A Geographical Description of the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland, with the Isles and Terrotories thereto belonging. And for the better perfecting of the said work, there is added an Alphabetical Table of the Names, Titles and Seats of the Nobility and Gentry that each County of England and Wales is, or lately was, enobled with. Illustrated with a Map of each County of England besides several general ones. The like never before published". Thomas Ryecroft.

- "Camden's description of Hampshire, 1610 translation". www.geog.port.ac.uk.

- Carpenter, Pete (2 June 2021). "Ashley Range in the New Forest National Park". www.new-forest-national-park.com.

- "BBC – History – World Wars: Training SOE Saboteurs in World War Two". www.bbc.co.uk.

- "Wartime school for spies revealed". BBC News. 15 March 2005.

- Lett, Brian (30 September 2016). SOE's Mastermind: The Authorised Biography of Major General Sir Colin Gubbins KCMG, DSO, MC. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781473863828 – via Google Books.

- The United Kingdom's World Heritage: Review of the Tentative List of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (PDF) (Report). Department for Culture, Media and Sport. 2011.

- "New Forest national park date set". BBC News. 24 February 2005. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- "Who runs the National Park?". New Forest National Park Authority. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "New Forest District Council to receive annual report on climate change". Advertiser & Times. 23 January 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- Review: The Preservation of the New Forest: Report of the New Forest Committee, 1947 H. C. Darby. The Geographical Journal, Vol. 112, No. 1/3. (Jul. – Sep., 1948), pp. 87–91.

- "Commoning". New Forest National Park. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- "New Forest National Park – Learning About – Numbers 30,000 to 120m". New Forest National Park website. New Forest National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 8 September 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- South East and London National Character Area map at www.naturalengland.org.uk. Accessed on 3 April 2013.

- "Flint gravels, which at Pipers Wait [249 165] near Nomansland, form the highest point (129 m above Ordnance Datum (OD)) in the New Forest" – R. A. Edwards, E. C. Freshney, I. F. Smith, (1987), Geology of the country around Southampton: memoir for 1:50,000 sheet, page 1. British Geological Survey

- "The walk connects the two highest points in the New Forest. At 422 ft, Pipers Wait (A) just shades it by a couple of feet over Telegraph Hill (C)." – Norman Henderson, (2007), A Walk Around the New Forest: In Thirty-Five Circular Walks, page 85. Frances Lincoln

- "The New Forest Cicada Project". New Forest Cicada Project. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Hamilton, Anthony (March 2013). "Two UK Gladiolus: Anthony Hamilton discusses the status of naturalized 'Byzantine' gladiolus, also common in gardens, and a 'native species' found in the New Forest" (PDF). The Plant Review. Royal Horticultural Society: 50–55.

- Wild Devon The Magazine of the Devon Wildlife Trust, page 8 Winter 2009 edition

- Chris (1 July 1905). "Article about Brusher Mills". Southernlife.org.uk. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- "BBC item about Brusher Mills". BBC. 24 July 2002. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- Wildlife and its management in The New Forest (PDF), Forestry Commission, January 2004, p. 1, retrieved 30 August 2011

- "A quarter century of saving sand lizards". The Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Trust. 16 May 2017.

- Cardlidge, Sarah (23 September 2015). "Tributes paid to popular New Forest keeper". Bournemouth Echo.

- "UK SAC details". Jncc.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- "UK SPA list". Jncc.gov.uk. 25 September 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- "UK and dependencies Ramsar Site list". Jncc.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- Barker, Ian (27 September 2012). New Forest Biodiversity Action Plan (Report). Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- Update 6 Archived 2 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine from DEFRA

- Landscape Protection – New Forest National Park Archived 3 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine from DEFRA

- Judgment of the High Court in Meyrick Estate Management Ltd v. Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, [2005] EWHC 2618 (Admin), 3 November 2005, from BAILII.

- "New Forest National Park – Frequently asked questions – Boundary Issues". Newforestnpa.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- McKay, I. (Ed.), A New Forest Reader: A Companion Guide to the New Forest, its History and Landscape, Hatchet Green Publishing, 2010 (ISBN 978-0-9568372-0-2)

- Magicyop (15 December 2005), Transcript of Erin Hunter Chat!, archived from the original on 4 March 2008, retrieved 8 April 2014

- Fox, Killian (29 March 2020). "A Room with a Review: Critics on the Art of Home Working". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- Taylor, Sally (7 August 2020). "Mark Kermode: Cinema and Streaming Can Both Thrive". BBC News. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

Further reading

The following out-of-copyright books can be read online or downloaded:

- Wise, John Richard de Capel (1863). . Smith, Elder and Co. – via Wikisource.

- Cornish, Charles John (1894). The New Forest. New York: MacMillan & Co.

- Godfrey, Elizabeth (1912). The New Forest. Ernest William Haslehust (illustrator). Blackie & Son Ltd.

Extracts from the above texts have been brought together by the New Forest author and cultural historian Ian McKay in his anthologies:

- McKay, Ian, ed. (2011). A New Forest Reader: A Companion Guide to the New Forest, its History and Landscape. Hatchet Green Publishing. ISBN 978-0956837202.

- McKay, Ian, ed. (2012). The New Forest: A Pocket Companion to the New Forest, Its History and Landscape. Hatchet Green Publishing. ISBN 978-0956837288.

These anthologies also include writings by William Cobbett, Daniel Defoe, William Gilpin, William Howitt, W. H. Hudson, and Heywood Sumner.

External links

- The Official New Forest Tourism Website | Information on visiting the National Park

- New Forest National Park Authority

- New Forest | Forestry England

- New Forest Gateway – Film, TV, Picture Resource / Historical Book Publications Online

- SAC designation including extensive technical description of habitats and species

- Designation as a national park:

- Minister says yes to New Forest National Park (DEFRA press release, 28 June 2004)

- New Forest National Park becomes a reality (DEFRA press release, 24 February 2004)

- The New Forest National Park (Countryside Agency press release, 1 March 2005)

- New Forest National Park Inquiry from the Planning Inspectorate

- Maps of the boundary

- New Forest at Curlie