Baldwin-Westinghouse electric locomotives

Baldwin, the locomotive manufacturer, and Westinghouse, the promoter of AC (alternating current) electrification, joined forces in 1895 to develop AC railway electrification. Soon after the turn of the century, they marketed a single-phase high-voltage system to railroads. From 1904 to 1905 they supplied locomotives carrying a joint builder's plate to a number of American railroads, particularly for the New Haven (the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad) line from New York to New Haven, and other New Haven lines. Westinghouse would produce the motors, controls, and other electrical gear, while Baldwin would produce the running gear, frame, body, and (in most cases) perform final assembly.

Baldwin-Westinghouse electric locomotives

Experimental locomotives

In 1895 a box-cab locomotive 32 feet (9.8 m) long with two four-wheel trucks and weighing 46 short tons (41.1 long tons; 41.7 t) was built at the East Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania) works of Westinghouse. It was used for more than a decade of AC and DC experimentation. Sold in 1906 to the Lackawanna & Wyoming Valley Railroad in northern Pennsylvania as a 600 hp (450 kW) 500 V DC locomotive, it was in service until 1953.[1]

No. 9, the first single-phase locomotive built in America was completed in 1904. Weighing 126 short tons (113 long tons; 114 t) and operating on 6600 V AC, it had six 225 hp (168 kW) traction motors with quill drive on two three-axle trucks.[2]

Indianapolis-Rushville interurban

In 1905 a 41-mile (65 km) interurban line between Indianapolis and Rushville, electrified by Baldwin-Westinghouse at 3300 volts single-phase AC, was opened by the Indianapolis & Cincinnati Traction Company.[3]

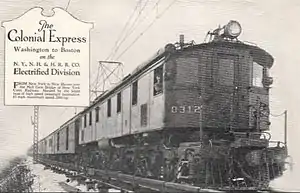

New Haven electrification

In 1905 the New York, New Haven & Hartford investigated electrification for their 35 miles (56 km)-line from Grand Central Station to Stamford, with a possible extension to New Haven, Connecticut. Electrification for passenger service was required in New York. Operation of such trains to the suburbs was preferred to changing to steam outside New York. Electrification of the busy main line would increase the capacity of the existing four tracks. Proposals were obtained from General Electric (GE) and Westinghouse. Both companies submitted a variety of AC and DC schemes, though GE favoured DC electrification. But New Haven chose single-phase AC as proposed by Westinghouse, at 11 kV 25 Hz. The generating station was at Cos Cob.[3]

The New Haven EP-1

An initial order of 35 EP-1 locomotives were supplied from 1905 to 1907. The design was similar to No. 9 above, with two two-axle trucks and a Westinghouse gearless quill drive, which supported the motor on the truck frame and reduced the unsprung weight. The locomotives weighed 102 tons and were 37 ft 6½in long. They had to operate over the 12 miles of New York Central track electrified at 660 V DC third rail from Grand Central to Woodlawn, so had AC/DC series commutator motors; the four Westinghouse 130 motors had a total hourly rating of 1,420 hp (1,060 kW). The locomotive could change from AC to DC without stopping; power pickup was by eight third-rail shoes which could be lowered, plus two large AC pantographs and a small pantograph for DC where short sections through switches were too complicated for third-rail supply. A second order of six supplied in 1908 had design changes, including guide wheels at each end to obviate "nose" or oscillation at high speed. The highly successful class operated to 1947, although some were retired from 1936.[4]

New Haven experimental locomotives

In 1910 New Haven decided to extend electrification, and to electrify freight and switching as well as passenger service. Before placing a major order, the line ordered four experimental locomotives from Baldwin-Westinghouse, built in 1910 to 1911. They were numbered No. 069, No. 070, No. 071 and (?).[5]

The New Haven EF-1

While three of the experimentals were equipped for passenger service, the EF-1 was intended for freight service. As such, it did not have train-heating boilers or third-rail DC equipment.[6]

The New Haven switchers

Steeple-cab B + B switchers were supplied in 1911-1912 (16) and 1927 (6); total 23. They weighed nearly 80 tons and had a maximum tractive effort of 40,000 lbs.[7]

The New Haven EP-2

Five 1-C-1 + 1-C-1 passenger locomotives were supplied by Baldwin-Westinghouse in 1919. Similar to the 1912-1913 locomotives, they were 69 foot long and weighed 175 tons, with a top speed of 70 mph (110 km/h). The hourly rating was 2460 hp, and maximum tractive effort of almost 50,000 lb. A further 12 were supplied in 1923 and 10 in 1927; totaling 27.[8]

Steeple Cab Electrics

Examples served with the Oshawa Electric Railway in Oshawa, Ontario. These were delivered in the 1920s to provide freight service within the city, serving mainly the General Motors plant.[9] One example bearing number 300 from Oshawa is preserved at the Seashore Trolley Museum. This all-steel example is 36 feet long, 10 feet wide, 12 foot 7 inches high, weighing 100 000 lbs. It has four motors, resting on two Baldwin MCB trucks. "It is typical of many Baldwin-Westinghouse locomotives used on electric railways from Maine (the Portland-Lewiston and the Aroostook Valley) to California (the Pacific Electric and the Sacramento Northern).".[10] Others are still in service with the Iowa Traction Railway.[11]

The New Haven EF-3

This 1942-1943 order for 10 freight locomotives was split between GE and B-W. They were AC only, weighed 246 tons, and rated 4860 hp with a tractive effort of 90,000 lb. In 1948 the 5 Baldwin-Westinghouse locomotives were equipped with train-heating boilers for passenger service.[12]

The Great Northern Z-1 class

_(14574492017).jpg.webp)

Z-1 class locomotives were supplied to the Great Northern Railway for the new longer and lower Cascade Tunnel and the extended electrification of the line through the Cascade Range. They were used from January 1927 through the old tunnel, and the line through the new tunnel was opened in 1929. The old tunnel used three-phase power, so eight miles of the overhead on the line to be abandoned were modified to single phase AC (11 kV, 25 Hz), and steam locomotives were used over a short connecting section of line.

Two were supplied in 1926 and three in 1928. Each Z-1 locomotive had two semi-permanently coupled 1-D-1 box-cab units; the pair weighed more than 371 tons with an hourly rating of 4330 hp and a continuous tractive effort of 88,500 lbs per unit (177,000 lb per pair) and a maximum starting effort of 189,000 lb. The locomotives had a motor-generator set with a synchronous AC motor and DC generator, which supplied the Westinghouse 356-A traction motors geared to each driving axle. They were equipped for multiple-unit control and regenerative braking. A pair of Z-1s with four units could move a 2900-ton train over the 2.2% maximum gradient of the new Cascade line.[13]

See also

Notes

- Middleton 1974, pp. 76–77.

- Middleton 1974, p. 77.

- Middleton 1974, p. 76.

- Middleton 1974, pp. 76–79.

- Middleton 1974, pp. 79–80.

- Middleton 1974, p. 84.

- Middleton 1974, pp. 84, 97.

- Middleton 1974, pp. 92, 97.

- "OSHAWA RAILWAY FREIGHT MOTOR 300". trainweb. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- "OSHAWA LOCOMOTIVE 300". Seashore Trolley Museum Collection. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- (1) POTB 101 (October 17, 2020). "Iowa Traction 50". Mason City, Iowa: Railroadforums.com. Archived from the original (photograph) on November 2, 2020. Retrieved November 2, 2020..

(2) Streiff, Jeffrey (September 20, 2019). "IATR 54". Mason City, Iowa: RR Pictures Archives.net. Archived from the original (photograph) on November 3, 2020. Retrieved November 3, 2020..

(3) Van Cleve, Jeff (June 23, 2019). "IATR 60". Emery, Iowa: RR Pictures Archives.net. Archived from the original (photograph) on November 3, 2020. Retrieved November 3, 2020.. - Middleton 1974, p. 97.

- Middleton 1974, pp. 163–169.

References

- Middleton, William D. (1974). When the Steam Railroads Electrified. Milwaukee: Kalmbach Publishing. ISBN 0-89024-028-0.