History of Swindon

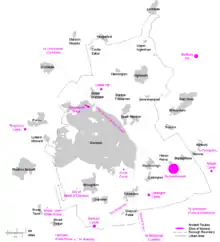

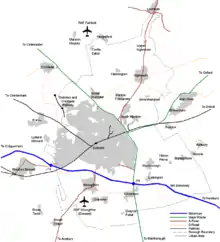

Swindon is a town in Wiltshire in the South West of England. People have lived in the town since the Bronze Age and the town's location, being approximately halfway between Bristol and London, made it an ideal location for the Locomotive Factories of the Great Western Railway in the 19th century.

Swindon has grown from a population of just 1,198 in 1801 to over 150,000 in 2001.[1]

Pre-history

The modern town of Swindon is built on and around a hill that stands over 450 ft (140 m) above sea-level, now known as Swindon Hill. Its location to the north of the Marlborough Downs and on the southern end of the Vale of White Horse, with access to the River Cole and others, made it suitable for use as farming land.[2]

There have been settlements around the hill since pre-historic times, but no clear evidence of occupation on the hill has been found. Central parts of Swindon Hill and the Old Town have been extensively quarried, especially beds of Purbeck Stone, as is clearly evidenced in the first British Geological Survey for the area. There is no clear evidence of any substantial fortifications.

However, digs around Swindon's former quarry sites and during building works have uncovered limited prehistoric finds, including Bronze Age relics, with suggested burials, flint tools, and pottery. Later Iron Age artifacts have also been found. Overall there is limited survival potential in the area of Old Town, but what remains is locally relevant.

Archaeological excavations around Swindon Hill have revealed pre-Roman farms and an additional Iron Age farm complex was discovered on lowlands to the north of Swindon in the 1970s.[2] There are various monuments and earthworks nearby, including Liddington Castle, Barbury Castle, Avebury and the White Horses of Uffington, Hackpen and Marlborough.

In addition to later prehistoric occupation, Mesolithic activity can be considered as probable on the hill around Old Town, but the evidence is now very likely lost to urbanization. A cluster of Mesolithic and other flint finds are listed (Sites and Monuments Records and Historic Environment Records) along the low ridges formed by the Jurassic outcrop which underlies Old Town, the west end of which was quarried. This includes an area around the public park called The Lawns, which straddles either side of a stream channel, just to the east of Old Town. The finds are from various building works on the higher ground to the south and west of the old stream. Further Sites and Monuments Records show Mesolithic and other prehistoric lithics have been identified in multiple places along the low ridge running south-west from Swindon Hill (at the highest and most westerly part) beyond Coate Water Country Park, in close proximity to the Coate Stone Circle, and to the east of the Dorcan Stream.

A D Passmore, a member of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society and The Prehistoric Society, noted a possible sarsen stone setting somewhere beyond the current northern limit of The Lawns, on the slightly higher ground north of the current public park, but now lost to 19th and 20th century urbanization. He also noted various other stone settings and rows around the area, not all clearly located, but including features around the modern Coate Water Country Park. Archaeological opinion has differed on the status of Passmore's interpretation, with some suggesting that all of the stones were natural, and likely sets of sarsen erratic boulders, presumably derived as a lag deposit from long dissolved chalk and possibly moved by very ancient glaciations. It is, however, noteworthy that the only stones noted by Passmore which have survived urbanization, expedient quarrying, and other destruction, form the Coate Stone Circle. This is protected by English Heritage,[3] and understood to be a stone circle of unknown date. It is unclear whether all the stones actually stood on their longest axis, making the circle potentially akin to a recumbent stone circle, rather than standing stones. The surviving circuit of stones is well buried in the soil, with only low and wide tops showing. There has been very limited field investigation, but this has included a geophysical survey.

To the west and south of Coate Stone Circle, on the slightly higher ground, the Oxford Archaeology Unit and Wessex Archaeology Unit identified and reported in 2006 and 2007 a large spread of Mesolithic finds found through fieldwalking. This is in close proximity to a feature listed as the "Coate Mound" in the Historic Environment Records for Wiltshire. Just to the east of the Coate Stone Circle is the current channeled form of the Dorcan Stream, arising as one of several small but active natural springs from the area around the south, around the hill at Badbury Wick, itself a site of Bronze Age occupation. Beyond the eastern side of the Dorcan Stream, the ground rises, and on the top/edge of the west-facing slope, with a view back over the stream, and towards the area of Coate Stone Circle, a further assemblage of Mesolithic finds was recovered during housing development in 2014, as well as evidence of other prehistoric activity, including Bronze Age cremations and a rock-cut ring ditch.

The Historic Environment Records show further evidence of scattered Bronze Age occupation around the site of the Great Western Hospital. However, clear Neolithic evidence is quite limited for the areas discussed. Iron Age occupation has been identified and excavated in fields to the north of Coate Stone Circle, and a survey of nearby round barrow features has been conducted. Further survey of earthworks immediately to the north of Coate Stone Circle suggests the remains of a medieval settlement of the Deserted Medieval Village type. Additionally, a Romano-British farmstead has been located in the low-lying fields just to the south of Coate Stone Circle.[4][5]

The Romans in Swindon

A Roman town called Durocornovium existed to the east of Swindon from the 1st to 4th centuries, located in present-day Wanborough.[6] It is probable that Swindon began life as a settlement linked to a military encampment in the early days of the Roman occupation. The place that is now Swindon was on the junction of two Roman roads, one leading south from Cirencester towards Marlborough and the other south eastwards to Silchester (see Ermin Way). Evidence exists to show that Swindon's quarries were in use at this time to produce stone for villas and clay from the Whitehill region (now West Swindon) was used to produce Whitehill Ware pottery.[7]

Burial grounds dating to the 4th century have been found in Purton,[2] but the most substantial find was made in 1996, when contractors developing an area of Groundwell Ridge uncovered the buried walls of Roman buildings. Described as "a site of great importance, with a large complex of buildings, a hypocaust (a system of under-floor heating, usually found as part of Roman bath houses), walls covered with painted plaster and a carefully designed and constructed water supply.",[8] the area is now owned by Swindon Borough Council and English Heritage, and is protected as a Scheduled Ancient Monument. On 28 and 29 June 2003 the site was featured as parts of Channel 4's archaeological television programme Time Team in its 'Big Dig' weekend.

The Anglo-Saxons

With the recall of the legions to Rome in the 5th century, the Roman settlements around Swindon declined rapidly. Although Germanic settlers may have been present earlier, the West Saxons advanced from the south coast in the 5th century and brought Swindon under their control after the Battle of Beranburgh, reportedly at Barbury Castle in 556.

There is some possibility of another battle fought against the native Romano-Britons at Wanborough in 591. Claims have been made that a further battle was fought at Wanborough in 717 between Ceolred, King of Mercia, and Ine, King of Wessex, and the area was still in dispute in 825 as demonstrated by the Battle of Ellandun

The West Saxons built a farming community based on the top of Swindon Hill, with remains of wood-framed and Plaster huts found near to Market Square. Anglo-Saxon pottery and cloth finds suggest the town was still occupied throughout the 6th and 7th centuries.[2]

The Anglo-Saxons left many lasting marks on the landscape and surroundings, including names for local places and features and ultimately the future name of Swindon, possibly derived from the words "Swine" for "Pig" and "Down" for "Hill".

Medieval Swindon

Recorded in the Domesday Book as both Suindone and Suindune in 1086, the settlement was assessed at 12¾ hides and divided into five holdings.[9] The largest holding, under the ownership of Miles Crispin and Odin the Chamberlain, was later known as the manor of High Swindon. Five hides, known as the manor of Nethercott, were owned by Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, Earl of Kent, and half-brother of King William the Conqueror. Other holdings recorded in the Domesday Book are at West Swindon, where 2 hides were held by Ulward and 1½ by Alvred of Marlborough. Smaller estates at Walcot, Even Swindon and Broome are also noted.[2]

Following the imprisonment of Odo for having planned a military expedition to Italy, High Swindon reverted to the Crown until the reign of Henry III in the 13th century who gave it to William de Valence, Earl of Pembroke. Under the ownership of William de Valence it is recorded that, in 1259, the first documented market was held in Swindon.[2]

The first recorded members of parliament for Swindon are John Ildhelfe and Richard Pernaunt, who were elected to the Model Parliament of King Edward I in 1295. Swindon became part of the constituency of Cricklade in 1660. (See also History of government in Swindon.)

In 1334 there were 248 poll tax payers in the town.

The oldest recorded street in the town is Newport Street, near the cattle market (dated 1346), originally called Nyweport Street meaning 'New Market'.[2] The cellars of some houses in modern-day Newport Street are thought to date back to this era.

During the 14th century, the manor of High Swindon was known as Hegherswyndon. High Swindon has perhaps seen the least development of all the manors, remaining largely unchanged until the 19th century.

During the period from 1086 onwards, the boundaries of High and West Swindon were re-arranged into Over and Nether Swindon, which became known as West and East Swindon in the 16th century. Nethercott became the manors of Eastcott and Westcott in the same century. Eastcott was bought by the Vilett family in the 18th century (now marked by Eastcott Hill in today's town) and Westcott was purchased by the Goddard family in the 18th century.[2] In 1563, the manor of Swindon (East and West Swindon) was purchased by Thomas Goddard. At the time of the purchase, Swindon's economy revolved around agriculture, with sheep farms to the south, pigs and cattle to the north, supported by trades such as tanners and woolmongers in the town.

The 1700s

An Ecclesiastical Count (a type of 'guess census', an estimation of growth from 25 years previous performed by the Christian Church) was undertaken in 1705. The figures for Swindon show – 600 men, women, children and 26 freeholders.[2] With the Goddard's now owning the Manor of Swindon in its entirety, and being by right Lords of the Manor – their income from rent, leases and taxation increased. In 1717, the Michaelmas Day assizes for rent due to the Lord of Manor show 45 tenants and 34 Leaseholders (rent due on Michaelmas and Lady Day for leases). One record from the time shows – 'Richard York, paying eight pence a year for "his house late a barn"'.[2]

The main sources of revenue for the town were now from agriculture, livestock and quarrying with the Purbeck Stone quarries being worked to provide stone for minor expansion and house-building.

The first non-market shops also appeared around this period, moving Swindon steadily away from a purely barter driven economy, with Robert and Margaret Boxwell opening the first recorded grocer independent of the market on the High Street in 1705.[2] This business lasted at least 50 years, records show at that time they were importing tea and sugar from London.

Manorial records of Swindon from 1700 to 1900 show that many families chose to remain here instead of seeking fortunes elsewhere – 'Swindon was not a town that its occupants readily moved from or changed'.[2]

The town's biggest employers in 1701 were the quarries, with 15 roughmasons or stonecutters and 40 labourers listed.

Manorial records also note the following tradesmen/families in the town – Four bakers, four butchers, five innholders, 1 cooper, 1 mercer, 1 draper, 1 glover, 1 currier, 1 saddler, 3 weavers. 20 servants, 4 tailors, 10 cobblers, 4 blacksmiths, 2 carpenters, 1 chandler, 1 cheese factor, 1 joiner, 2 slaters, 1 wheelwright, 1 ironmonger, 1 glazier and 1 surgeon.

The average diet at the time consisting of bread, meat and beer.

Roads

With the expansion of the Quarries and also the introduction of the Turnpike Act (1706), the four main access roads into the Town were turned into turnpikes between 1751 and 1775.[2] With the Swindon to Faringdon road completed in 1757 and the Swindon to Marlborough road in 1761.

Toll houses were also placed on the roads to Stratton St Margaret, Marlborough, Devizes, Wootton Bassett and Cricklade.

Residents of Rodbourne Cheney and the Liddiards came into Swindon via roadways that linked Shaw and Rushey Platt with the gate at Kingshill.

The amount levied depended on the type of cart, the number of horses used and the width of wheels (as the narrower wheels caused more damage to the road).

Roads were kept clean and in good repair by auctioning lots to townspeople who could possibly sell 'road scrapings and parings' (manure etc.).

This practice continued at least until 1846, at which time the auctioneers Dore & Fidel published the lots for sale as

"1, From Swindon to the top of Kingshill. 2, From thence to the canal. 3, From thence to the hand post at Mannington. 4, From thence to the brow of the hill at Whitehill. 5, From thence to the Lodge Gate. 6, From thence to the west corner of Agbourn Coppice. 7, From thence to the Fourth Mile-stone. 8, From thence to the Gate, in the occupation of Ann Rudler. 9, From thence to the stream of water crossing the road by William Watt's. 10, From thence to the Turnpike Gate. 11, From thence to the borough of Wootton Bassett. Swindon Parish Road. 12, From Mr Blackford's Corner to the Wharf Bridge, and 13, The scraping and sweeping of all the streets in the Town of Swindon."[2]

Lot 13, being the roads of the Town itself would provide the most work and also the best rewards. Additional terms were stipulated for this lot, including the requirement that sweepings be removed every Thursday and Saturday. Markets at this time were held on Monday's, so there would have been a rich covering on the road by the time of its Thursday sweeping.

The Goddard family – Lords of the Manor of Swindon

The Goddard family was established within Swindon prior to the 15th century. Thomas Goddard of Upham acquired the manor in 1563 and his descendant family were Lords of the Manor up until the 20th century. The estate included the area known today as the Lawns, and was bounded by the High Street and the site of Christchurch.

On 22 January 1658, Francis Bowman, guardian of Thomas Goddard, leased a "mansion house lately occupied by Anne Goddard in Swindon" to William Levett, a courtier who had accompanied King Charles to his execution. His sons included Henry Levett, physician of London Charterhouse; Levett's son William was principal of Magdalene Hall, Oxford, and later Dean of Bristol.)[10] Later Goddard family leases to Levett, who retained his farm within Savernake Forest, would come to include other lands in Swindon. By then Levett was working as surveyor for the Duke of Somerset. In the lease of 5 April 1664, the lease notes that "the Parke etc." is included as well as the Goddard mansion.[11] Two of Levett's children are buried at Holy Rood Church in Swindon.[12]

The last of the Goddard male line, Major Fitzroy Pleydell Goddard, a diplomat, died in 1927. His widow, Eugenia Kathleen, left Swindon in 1931. Subsequent to this, the house remained empty until it was occupied by British and American forces during World War II. Damaged by the military, it was bought from The Crown by Swindon Corporation in 1947 for £16,000. The sale included 53 acres (210,000 m2) of land, the Manor house and the adjacent Holy Rood Church. The house itself was derelict by 1952 and demolished. The Manor grounds were opened as parkland and remain so. Today the wood, lake, sunken garden, elements of the walls and the gateposts at the entrance to Lawns are all open to the public. The former stables are now the Planks auction house.

Markets

The economy of Swindon has, pre-predominately over the years, depended on Land, agriculture and livestock markets. William de Valence, Earl of Pembroke (½ brother of Henry III) is recorded as having held a market in Swindon from 1259. It is from these records that the name Swindon first appears, as well as 'Chepyng Swindon' in 1289 and 'Market Swindon' in 1336.[13]

Although Thomas Goddard was granted a weekly market and two fairs a year in 1626, the Market in Swindon was in decline by 1640. However a cattle plague hit nearby Highworth in 1652, allowing Swindon's livestock sales to increase. In 1672, John Aubrey remarked "Here on Munday every weeke a gallant Markett for Cattle, which increased to its new greatnese upon the plague at Highworth."[2]

Swindon Market was one of the 32 weekly markets held throughout Wiltshire up to 1718.

In 1814, John Britton passed through Swindon and recorded 1,600 people and 263 houses in the town. He also wrote of the weekly corn market, fortnightly cattle market and regular Horse sales. However, by the mid-19th century the cattle market was poorly attended.

A new Cattle Market site was built in 1873 to try to revive the Market, a site which remained until the late 1980s when the final auction was held. There is no longer a Cattle Market in modern Swindon.

The 1800s – canals and steam

The 19th century saw the beginnings of Swindon's growth, firstly through the Canals and later due to the Railway. Changes which helped the towns population double in the first half of the century from 1,198 in 1801 to 2,495 in 1841.[1] With new houses being built along Bath Road using stone from the local quarries, Swindon continued to move away from being a purely agricultural town.

However, this did not stop an observation being made in 1830 that Swindon was "a town of two principal streets."[2] and also "A small village of no importance on the summit of the hill near the important market town of Highworth."

The Canals came to Swindon in the early part of the century, to be replaced later by the siting of the Great Western Railway's Works and the building of New Swindon in the mid-19th century.

Swindon at the beginning of the 19th century was still mainly centred at the top of Swindon Hill, some farmhouses, cottages and small dwellings were scattered around its base. Today's suburbs of Coate, Broome, Westleaze, Walcott, Russia Platt (later Rushey Platt), Westcott, Eastcott, Rodbourne Cheney, Westlecot and Kings Hill were all still small hamlets. A number of these are now in areas considered to be in the town centre.

Eastcott became the focus of the new Swindon, with the Wilts and Berks Canal Company building Swindon Wharf and a number of canal buildings just north of the hamlet. Regent Circus is the site of a former orchard and a public house called the Red Cow (now recognised in the current pub named the Red Cow near to the original site).

A bridge placed across the canal in 1806 to provide access to a farm was later to become the Golden Lion bridge, now located in the centre of Swindon's main shopping area on Canal Walk. Up until 1840, what is known today as Swindon town centre was farms and fields.

Purbeck Stone quarries

From the mid-17th century till the end of 18th century, Swindon's economy began to increase with the exploitation of the Purbeck Stone (a type of limestone) quarries.

Stone from these quarries had been used from the time of the Roman occupation, Swindon stone has been found in Roman villas and settlements in the area.

Documented workings survive from 1641, with all new excavations sanctioned and taxed by the Goddard family. The quarries declined during the period 1775–1800, but rebounded during the building of the Wilts and Berks Canal. Stone was used in building the canal walls, buildings and also exported using it. In 1820, 101 tons of Swindon stone was transported along the canal.[2] This fell to 44 tons in 1845 with the introduction of the railway; however, the Great Western Railway buildings and the creation of Swindon New Town saw a resurgence in stone production. Quarrying activity ceased altogether in the late 1950s with the sites of two quarries being in the locations of Queens Park and Town Gardens in the modern town. The site of the former Okus Quarry is now a protected Site of Special Scientific Interest.

Canals

In 1775, an act of parliament was passed authorising the building of the Wilts and Berks Canal. A "waterway that would link the Kennet and Avon Canal at Semington, near Trowbridge with the River Thames at Abingdon.."[2] It reached Swindon in 1804 and Abingdon in 1810. In all, 58 miles (93 km) of waterway was created.

The canal enabled Swindon businesses and farmers to transport goods over a wider area and brought new residents from outside the county, among them navvies who settled after completion of the canal work. Ambrose Goddard, Lord of the Manor of Swindon at the time, was a shareholder in the canal company, and authorised a number of its land purchases along its eventual route, land which he himself owned.[2]

In 1813, another act of parliament was passed authorising the North Wilts Canal, a proposal by the Thames & Severn Canal Company and the Wilts & Berks Canal Company to link the existing Wilts and Berks Canal at Swindon with the Thames and Severn Canal at Latton, near Cricklade. Consisting of 9 miles (14 km) of waterway and twelve locks, it was completed in 1814. The two canals were consolidated in 1821 and brought together under the auspices of the Wilts & Berks Navigation Company.

A 70-acre (280,000 m2) feeder reservoir was built at Coate, a mile and a half south of the town, in 1822. This reservoir was created to keep the canal at a navigable level in the Swindon area.

With the railways providing a faster and cheaper method of transport, the canal was relatively unused by 1895. It was dredged in 1908, but declared ruined soon after. It was finally closed under the Wilts & Berks Canal Abandonment Act, 1914 and partly filled in.

Elements of the canal can still be seen in Swindon, with the route being remembered in the name of Canal Walk in the town centre. A new route for the canal to the south of the town is under development, with the first section opened at Wichelstowe in 2011.[14]

Brunel, the railway and Swindon the industrial giant

Swindon as reported in 1830 was still a quiet, market town –

Swindon is a market town in the hundred of Kingsbridge, eighty miles from London, thirty-eight from Salisbury, nineteen from Devizes, and eleven from Marlborough; pleasantly seated on the banks of the Wilts and Berks canal, by which navigation the trade of this place is much facilitated; – Mr William Dunsford, whose residence is at the Wharf, is the superintendent. Adjoining the church yard is a fine spring of water, which turns a corn mill within fifty yards of its source; and about a mile and a half south of the town is a reservoir, covering upwards of seventy acres, for supplying the canal. The population of the entire parish, according to the census of 1821, consisted of 1,580 inhabitants.[15]

This was to change markedly with the coming of the Great Western Railway.

In 1835 parliament approved the construction of a railway between London and Bristol, giving the role of Chief Engineer to Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

There are several stories relating to how it came to pass through Swindon, with a well circulated myth that Brunel and Daniel Gooch were surveying a vale north of Swindon Hill and Brunel either threw a stone or dropped a sandwich and declared that spot to be the new location of the works.

The siting of the Locomotive works transformed Swindon from a small Market town into a bona fide Railway town, boosted the population considerably and also provided medical and educational facilities that had been sorely lacking.

The Railway Works

The Great Western Railway was originally planned to cut through Savernake Forest near Marlborough,[2] however the Marquess of Ailesbury who owned the land, objected. The Marquess had previously also objected to part of the Kennet and Avon Canal running through his estate (see Bruce Tunnel).

With the Railway needing to run near to a canal at this point, and as it was cheaper to transport coal for trains along canals at this time, Swindon was the next logical choice for the works 20 miles (32 km) north of the original route.

Once the plan was set for the railway to come to Swindon, it was at first intended to bring it closely along the foot of the hill, so as to be as close as possible to the town without entailing excessive engineering works. However, the Goddard family, following the example quoted above of the Marquis (and many other landowners of the day), objected to having it near their property, so it was eventually laid a couple of miles further north.[2]

Eventually covering 320 acres (1.3 km2), it became the focal point for the creation of New Swindon and the influx of over 10,000 new residents in the next 50 years. "The period was the phenomenal growth of the GWR Works in Swindon where the GWR management concentrated, to a far greater degree than any other reailway company – most of their manufacture, repair, and serviceing operations. In the result there existed in Swindon by the end the 19th century, the largest industrial complex to be found in Europe."

In its heyday, it employed over 14,000 people and the main locomotive fabrication workshop, the A Shop was, at 11.25 acres (45,500 m2), one of the largest covered areas in the world.

Swindon Station

With the railway passing through town in early 1841, the Goddard Arms public house in Old Swindon was used as a railway booking office in lieu of a station. Tickets purchased included the fare for a horse-drawn carriage to the tracks down the hill.

Swindon railway station opened in 1842 with construction on the works continuing.

The Railway Village and New Swindon

The factory had to be immediately adjacent to the railway, and it was necessary for the workers to be housed as close as possible to it.

As the town of Swindon at that time was over a mile away on top of the hill, a modest Railway Village of 300 homes was proposed in 1841. Building began using stone from Swindon's quarries and also from stone excavated during the boring of Box Tunnel, 243 houses were completed by 1853 with the towns population being estimated at over 2,500. All 300 houses were completed by the mid-1860s.

Consequently, a new town was built, known as New Swindon. This town would remain both physically and administratively separate from Old Swindon until 1900.

The 1900s – boom town

1900–1910 – One Swindon

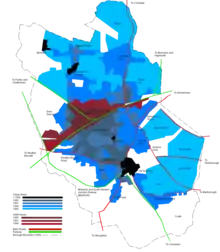

On 22 January 1900, Queen Victoria signed the charter granting Swindon Municipal Borough status, enacted 9 November.[16] The charter amalgamated Old and New Swindon into one town (population 45,006 in 1901),[1] enabling the pooling of resources from the two authorities. This provided enough money to open an electrical power station in 1903 on land bought by the new council at Lower Eastcott Farm (now located in Corporation Street).

Taking advantage of this, trams were introduced in September 1904.

In 1906, the Swindon Tram disaster occurred. A number 11 tram taking passengers from the Bath and West Show being held in Old Town suffered brake failure driving down Victoria Hill and crashed in Regents Circus, killing five.[16]

The Wilts & Berks Canal continued to fall out of use, with the last passing vessel being recorded in this year.[16]

1910–1930 – Fleming, flagpole riot and first Council estate

This period saw the town building its first cinemas, sited along the tram routes for ease of electricity distribution.

Swindon Town F.C. reached the semi-final of the FA Cup twice in three years whilst in the Southern League. Town player Harold Fleming was capped for England 12 times, scoring 9 times.[17]

The Wilts & Berks Canal was formally abandoned in 1914 and its Coate Water reservoir was turned into a pleasure park.

In 1919, a flagpole war memorial was the impetus for widespread rioting in the town by those who believed it to be disrespectful to the war dead.[16] The flagpole itself was later burned down and was eventually replaced by a wooden cenotaph. The existing stone cenotaph was introduced in 1920.

This period also saw the completion of the first council housing estate in Pinehurst, on the site of Hurst Farm. The houses on the new estate included such luxuries as electric light and bathrooms. Developers had also provided a local shopping centre, post office, community centre and temporary school.

The Swindon Advertiser and the Wiltshire, Berkshire and Gloucestershire Chronicle were bought by Swindon Press in 1920 and became the Evening Advertiser, now the Swindon Advertiser.[16] The Chronicle is today known as the Wiltshire Gazette and Herald.

1924 saw the highest employment ever in the GWR Railway Works, with 14,369 people employed in the various factories. On 28 April, King George V and Queen Mary visited the works, observing Number 6000, King George V in production.[16]

Fitzroy Pleydell Goddard, last of the Goddards and Lord of the Manor of Swindon, held the post of High Sheriff of Wiltshire during this period before his eventual death in 1927. Also, after only 25 years, Swindon's Trams were phased out by buses in 1929.

1930–1950 – War years

Swindon received its first purpose-built Maternity Hospital in 1931, now Kingshill House, located along Bath Road.[2] Prior to this, the only facilities available were in the crowded Milton Road GWR Medical Fund Hospital.

The 30s also saw more motor cars in private hands, with the town's purpose built car park erected behind the Town Hall.

Between 1934 and 1935, expansion began again in the Old Town area, with houses and estates being built along the Marlborough Road, for sale at £730 each, and also the new terraced housing estate in Walcot, where a house would cost £450.[16]

With the declaration of war and the onset of World War II, evacuees arrived in Swindon in 1939. Troops were stationed in churches and school halls throughout town with a contingent of British and American forces stationed in The Lawns, leading to the Manor house's eventual dereliction. Faringdon Road Park had trenches dug under trees and air-raid shelters added due to its location near to both the Works and the railway village.

The GWR Works became a war factory which in turn led to Swindon becoming a target for bombing raids, with the works' hooter used as one of the town's air raid siren due to its volume.[16]

The first air raid alerts sounded in June/July 1940 and Swindon received its first bomb in August. The device fell to the rear of Shrivenham Road and no-one was hurt. In October, bombs on York Road and Rosebery Street produced the Town's first fatalities.[16]

To provide recreation for the wartime community, the town's first public library was opened in 1943 in Regent Street with help from the Army. This was followed in 1946 with an arts centre, also on Regent Street.

1950–1970 – Modernising, expanding and Wembley

After the war, the influx of new residents to Swindon and the post–World War II baby boom increased the town's population to 68,953 by 1951[1] and it became clear that more housing was needed. This number was an increase of 13,000 residents since 1921.

New estates appeared throughout the 1950s: Penhill built from 1951, Walcot East in 1956 and then Park North and Park South.

The beginning of Swindon's association with car building also began in the 1950s, when Pressed Steel Fisher built a factory. The factory produced sheet metal pressings and bodywork for a variety of applications, including the railway, before eventual takeover by Rover. It is today owned by BMW and provides some facilities to the Honda car factory.

With the influx of new residents to industrial Swindon, medical facilities were over-burdened and a new hospital was proposed at Okus. Princess Margaret laid the foundation stone in 1957 of the Princess Margaret Hospital, which was completed in January 1960.

As Swindon entered the 1960s the population increase of 22,000 since 1951 brought the total number of residents to 91,775 in 1961.[1] This led to further outward expansion towards the east, establishing the residential areas of Dorcan, Eldene, Covingham and Liden.

The new hospital and new residents heralded an era of redevelopment in the town, with the council buying houses around the town centre for slum clearance[2] and transformation into retail units and shops. For safety, the town centre began pedestrianisation, with vehicle gates placed at Bridge Street, Fleet Street and Regent Street. Originally only closed to traffic from 10am till 5pm on Saturdays, this was expanded to the eventual pedestrianisation of the main shopping area and paving over of the existing roads and canals.

Swindon's role as a major railway locomotive manufacturer ended in 1962, with work changing to focus on repairs to carriages and engines and large portions of the site sold. However, in 1967, the retailer WH Smith moved its book distribution centre to the town,[18] a move designed to take advantage of Swindon's central placing. Other companies followed suit in the 1970s.

Construction began on the M4 motorway in the late 1960s to provide quick and easy access from the region into London.

In 1969 Swindon Town F.C. recorded the best result in its history, winning 3–1 in the League Cup Final against Arsenal at Wembley Stadium, a match watched by close to 100,000 people. The club later added the Anglo-Italian League Cup Winners' Cup to the 1969 honours, beating AS Roma 5–2 over two legs.

1970–1990 – From the railway to offices

The M4 motorway opened in 1971, providing Swindon with two motorway junctions (numbers 15 and 16). In the town centre, which was under redevelopment, smaller family-owned stores were replaced by large chain stores. The development of the town included the erection of the Wyvern Theatre.

It wasn't until 1972 that the Princess Margaret Hospital, Swindon's main hospital, had a purpose-built accident and emergency unit. Until this time the hospital had been using temporary hut based facilities.

The oil company Burmah Oil built their world headquarters along Pipers Way in 1972, now owned by Burmah-Castrol.

Adding to Burmah Oil's ingress in the 70s, another large corporation, Hambro Life Assurance, established their headquarters in the town in the 1970s, with offices over the railway station and over Debenhams in the shopping area. The company name was changed to Allied Hambro in 1984 and Allied Dunbar in 1985, before its eventual purchase by Zurich Financial Services.

Following boundary changes in 1974, the Borough of Swindon merged with the adjacent Highworth Rural District to become the Borough of Thamesdown. The new authority oversaw the construction of the Brunel shopping centre in the same year and the 1976 opening of the Oasis leisure centre. The David Murray John Tower, a landmark dominating the town's skyline, was built as part of the shopping centre construction and is named after the Town Clerk who championed the boundary changes and ultimately Swindon's regeneration.[16]

In the 1980s Swindon expanded west, with Toothill and Freshbrook forming the area now known as West Swindon. It was here also that the first out-of-town shopping centre was built in Swindon, by Carrefour; it is now an Asda supermarket.

The GWR Works finally closed in 1986, although it was wound down slowly with some employees remaining until 1987. The Wills tobacco factory also closed in 1987, and its site is now the large Tesco store on Ocotal Way.

1990–2010 – Further expansion

On 1 April 1997 the area became known once more as the Borough of Swindon after the creation of a new unitary authority, replacing the Thamesdown name.

During the 1990s the town was extended northwards into the neighbouring parishes of Haydon Wick and Blunsdon St. Andrew, resulting in the construction of a further 10,000 houses in the new communities of Abbey Meads, Taw Hill and St. Andrew's Ridge. In the first decade of the 21st century the residential areas of Oakhurst, Redhouse and Haydon End – together known as Priory Vale – were developed, together with a new District Centre for North Swindon at the Orbital Shopping Park. The area is accessed by a dual carriageway outer ring road linking the A419 trunk road to West Swindon, named Thamesdown Drive in memory of the former Borough name.

In 2002 the New Swindon Company was formed with the brief to regenerate the town centre into a dynamic regional centre, reflecting the importance of Swindon in the region and to give the town the centre it deserves.

In 2010 Swindon Borough Council established Forward Swindon, the company tasked with delivering and facilitating economic growth and property development in the town.[19]

See also

Notes

- "Swindon Census Information". Wiltshire County Council. Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- Child, Mark (2002). Swindon : An Illustrated History. United Kingdom: Breedon Books Publishing. ISBN 1-85983-322-5.

- Historic England. "Stone circle immediately north east of Day House, Coate (1016359)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- http://www.largeimages.bgs.ac.uk/iip/mapsportal.html?id=1001745

- "Wiltshire and Swindon Historic Environment Record | Wiltshire Council". Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- Codrington, Thomas (1903). Roman Roads in Britain: Chapter X: Roman Roads from London to Silchester and the West – continued.

- "Groundwell Ridge". Archived from the original on 13 December 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2006.

- "Groundwell Ridge – Swindon's Roman Heritage". Swindon.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 15 February 2005. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- Swindon in the Domesday Book

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- "See leases to William Levet(t) by Francis Bowman, Gent., guardian of Thomas Goddard, Goddards of North Wiltshire, Goddard family of Swindon, Wiltshire". A2a.org.uk. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- Jefferies, Richard (1896). Jefferies' Land: A History of Swindon and Its Environs, Richard Jefferies, London, 1896. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- "Wiltshire". Gazetteer of Markets and Fairs to 1516. Institute of Historical Research. 18 June 2003. Retrieved 6 December 2006.

- "Waterside Living comes to Swindon with homes in New Canal Village". Wilts & Berks Canal Trust. 10 April 2011. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Pigot & Co (1830). National Commercial Directory for Cornwall, Dorsetshire, Devonshire, Somersetshire and Wiltshire. United Kingdom. Retrieved 6 December 2006.

- The Swindon Society (2000). A Century of Swindon. United Kingdom: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2889-1.

- Dick Mattick (2002). 100 Greats : Swindon Town Football Club. United Kingdom: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-2714-8.

- "History of WHSmith". www.whsmithplc.co.uk. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- "Forward Swindon". Forward Swindon Limited. Archived from the original on 2 August 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

External links

- Swindon Collection – Local Studies Library – Holds copies of all local printed books and periodicals, newspaper archives, census and family history records and historical maps

- Swindon Collection Local Studies Gallery – Free online gallery of photographs, postcards, maps, portraits and other local material

- Historic Swindon video clips, photos and postcards – BBC Wiltshire

- Roman finds – Groundwell Ridge community website

- Groundwell Ridge Villa – English Heritage

- History of Swindon – Swindon Borough Council

- Swindon's Heritage – SwindonWeb

- Newsreel footage of Swindon 1918–1969 – British Pathe