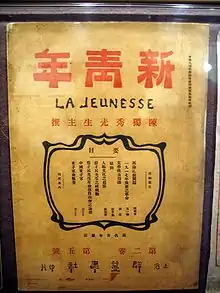

New Youth

New Youth (French: La Jeunesse, lit. 'The Youth'; simplified Chinese: 新青年; traditional Chinese: 新靑年; pinyin: Xīn qīngnián; Wade–Giles: Hsin1 Chʻing1-nien2) was a Chinese literary magazine founded by Chen Duxiu and published between 1915 and 1926. It strongly influenced both the New Culture Movement[1] and the later May Fourth Movement.[2]

| New Youth | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 新靑年 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 新青年 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | New Youth | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| French name | |||||||||

| French | La Jeunesse | ||||||||

Publishing history

Chen Duxiu founded the magazine on September 15, 1915 in Shanghai.[3] Its headquarters moved to Beijing in January 1917 when Chen was appointed Chairman of the Chinese Literature Department at Peking University.[4] Editors included Chen Duxiu, Qian Xuantong, Gao Yihan, Hu Shih, Li Dazhao, Shen Yinmo, and Lu Xun. It initiated the New Culture Movement, promoting science, democracy, and Vernacular Chinese literature.[2][1] The magazine was the first publication to use all vernacular, beginning with the May 1918 issue, Volume 4, Number 5.

Influenced by the 1917 Russian October Revolution, La Jeunesse increasingly began to promote Marxism. Over its history, the magazine became increasingly aligned with the Chinese Communist Party.[3] The trend accelerated after the departure of Hu Shih, who later became the Republic of China's Education Minister. Beginning with the issue of September 1, 1920, La Jeunesse began to openly support the communist movement in Shanghai, and with the June 1923 issue it became the official Chinese Communist Party theoretical journal. It was shut down in 1926 by the Nationalist government. La Jeunesse influenced thousands of Chinese young people, including many leaders of the Chinese Communist Party.

Notable contributors

Chen Duxiu

Chen Duxiu founded La Jeunesse and also edited it in the early years.[5] The editorial policies clearly reflected his personal values by supporting the new and growing vernacular literature movement and the revolution against established societal norms, Confucian values, and the use of Classical Chinese.[1] Chen was the leader of the May Fourth Movement student demonstrations. He was also a founding member of the Chinese Communist Party and provided their theoretical platform.

Chen published "A Letter to Youth" (Chinese: 敬告青年) in the first issue of September 15, 1915.[6] The letter issued six challenges:

- Be independent and not enslaved (Chinese: 自由的而非奴隶的)

- Be progressive and not conservative (Chinese: 进步的而非保守的)

- Be in the forefront and not lagging behind (Chinese: 进取的而非退隐的)

- Be internationalist and not isolationist (Chinese: 世界的而非锁国的)

- Be practical and not rhetorical (Chinese: 实利的而非虚文的)

- Be scientific and not superstitious (Chinese: 科学的而非想象的)

The letter further emphasized the urgency of pursuing science and liberty in order to remove the twin chains of feudalism and ignorance from the general population.

Chen Hengzhe

Chen Hengzhe published her short story “Raindrops" (Chinese: 小雨点) in September 1920. She was the first female writer to use the new vernacular style. It was the first Chinese children's story. She also published a collection of her works entitled, Raindrops, in 1928. Chen was among the first ten women to study overseas on government scholarships. She graduated from Vassar College and the University of Chicago. The first vernacular Chinese fiction was her short story "One Day" (Chinese: 一日), published 1917 in an overseas student quarterly (Chinese:《留美学生季报》). This was a year before the publication of Lu Xun's "Diary of a Madman", which has often been incorrectly credited as the first vernacular Chinese fiction.

Hu Shih

Hu Shih was one of the early editors. He published a landmark article "Essay on Creating a Revolutionary `New Literature" (Chinese: 建设的文学革命论) in the April 18, 1918 issue. He wrote that the mission of this language revolution is "a literature of the national language (Guoyu, Chinese: 国語), a national language of literature" (Original Text: 国语的文学,文学的国语。). Hu then goes on to reason that for thousands of years, the written language was bound by scholars using Classical Chinese, a dead language of past generations. On the other hand, the vernacular is living and adapts to the age. He urged authors to write in the vernacular in order to describe life as it is. He further reasoned that Chinese literature had a limited range of subject matter because it used a dead language. Using a living language would open up a wealth of material for writers. Finally, he argued that massive translations of western literature would both increase the range of literature as well as serve as examples to emulate. This was a seminal and prescient essay about the modern Chinese language. Hu Shih was an important figure in the transformation of the modern Chinese written and printed language.[7]

In the July 15 issue, Hu published an essay entitled, "Chastity" (Chinese: 贞操问题). In the traditional Chinese context, this refers not only to virginity before marriage, but specifically to women remaining chaste before they marry and after their husband's death (Chinese: 守贞). He wrote that this is an unequal and illogical view of life, that there is no natural or moral law upholding such a practice, that chastity is a mutual value for both men and women, and that he vigorously opposes any legislation favoring traditional practices on chastity. (There was a movement to introduce traditional Confucian value systems into law at the time.) Hu Shih also wrote a short play on the subject (see Drama section below).

These are examples of Hu Shih's progressive views. They were quite radical at that time, which was only a short six years after the overthrow of the Chinese imperial system. That epic event, the Xinhai Revolution, developed two branches in the 1920s, the Nationalist (Kuomintang) and Chinese communist parties. He tried to focus the editorial policy on literature. Chen Duxiu and others insisted on addressing social and political issues. Hu was a lifelong establishment figure in the Nationalist government and left "La Jeunesse" when its communist direction became clear.

Lu Xun

Lu Xun was an important contributor to the magazine. His first short story "Diary of a Madman" (Chinese: 狂人日记) was published in "La Jeunesse" in 1918.[7] The story was inspired by Nikolai Gogol's story "Diary of a Madman". While Chinese literature has an ancient tradition, the short story was a new form at that time, so this was one of the first Chinese short stories. It was later included in Lu's first collection, A Call to Arms, (Chinese: 呐喊) which also included his most well known novella, The True Story of Ah Q, (Chinese: 阿Q正传). "Diary of a Madman" records a scholar's growing suspicion that the Confucian classics brainwash people into cannibalism. Lu Xun symbolized the cruel and inhumane nature of old traditional Chinese society structure in this manner. Despite being a harsh metaphor, it was not exceptional due to numerous other contemporary indictments of the old society which were equally scathing. Other fiction by Lu Xun published in La Jeunesse includes "Kong Yiji" (Chinese: 孔乙己) and "Medicine" (Chinese: 药).

Li Dazhao

Li Dazhao (1889–1927), had played an important role in the New Culture Movement and would soon become the cofounder of the Chinese Communist Party.[8] Li Dazhao was the magazine's chief collaborator in the Chinese Communist Party,[9] and published, among other things, an introduction to Marxist theory in the May 1919 issue of New Youth.[10] In it, he also argued that China, while not possessing a significant urban proletariat, could be viewed as an entire nation that had been exploited by capitalist imperialist countries.

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong, the founding father of the People's Republic of China, in his youth contributed articles against the oppression of women under Confucianism and on the importance of physical fitness.[2][9] "The well-known quotation of Mao Zedong (1893–1976), cited above, which compares young people to the morning sun, claimed for youth the authority to define the nation’s future and endowed it with all the power to make changes that would revolutionize society."[11]

Liu Bannong

Liu Bannong was an important contributor to the magazine starting from 1916, invited by Chen Duxiu.[12] His article "My View on Literary Reform: What is literature?" (我之文學改良觀) was published in "La Jeunesse" in 1917. He suggested both on the content and the form of literary reform.

Poetry, drama, and other fiction

Though perhaps most famous for publishing short fiction, La Jeunesse also published both vernacular poetry and drama. Hu Shih's "Marriage" (Chinese: 终身大事) was one of the first dramas written in the new literature style. Published in the March 1919 issue (Volume 6 Number 3), this one-act play highlights the problems of traditional marriages arranged by parents. The female protagonist eventually leaves her family to escape the marriage in the story. Poems published included those by Li Dazao (Chinese:李大钊), Chen Duxiu (Chinese: 陈独秀), Lu Xun (Chinese: 鲁迅), Zhou Zuoren (Chinese: 周作人), Yu Pingbo (Chinese: 俞平伯), Kang Baiqing (Chinese: 康白情), Shen Jianshi (Chinese: 沈兼士), Shen Xuanlu (Chinese: 沈玄庐), Wang Jingzhi (Chinese: 汪静之), Chen Hengzhe (Chinese: 陈衡哲), Chen Jianlei (Chinese: 陈建雷), among others.

References

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckely (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 271. ISBN 0-521-43519-6.

- Ash, Alec (3 May 2019). "New Youth in China". Dissent. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Ash, Alec (6 September 2009). "China's New New Youth". DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Xia, Chen (15 September 2015). "New Youth magazine's former office restored in Beijing". China.org.cn. Archived from the original on 14 October 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckely (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 267. ISBN 0-521-43519-6.

- Yuchen, Chang (2016). "From New Woodcut to the No Name Group: Resistance, Medium and Message in 20th-Century China". Art in Print. 6 (1): 10. ISSN 2330-5606. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckely (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 270. ISBN 0-521-43519-6.

- Song, Mingwei (2020). Young China: National Rejuvenation and the Bildungsroman, 1900–1959. Brill. ISBN 978-1-68417-560-4.

- Chow, Tse-tsung. "Chen Duxiu". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 1 June 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckely (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 272. ISBN 0-521-43519-6.

- Song, Mingwei (2020). Young China: National Rejuvenation and the Bildungsroman, 1900–1959. Brill. ISBN 978-1-68417-560-4.

- Hockx, Michel (2000-01-01). "Liu Bannong and the forms of new poetry". Journal of Modern Literature in Chinese 現代中文文學學報. 3 (2). ISSN 1026-5120.

Bibliography

- Chow, Tse-Tsung. The May Fourth Movement: Intellectual Revolution in Modern China. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1960). Detailed standard study of the movement, its leaders, and its publications.

- Feng, Liping (April 1996). "Democracy and Elitism: The May Fourth Ideal of Literature". Modern China (Sage Publications, Inc.) 22 (2): 170–196. ISSN 0097-7004. JSTOR 189342.

- Mitter, Rana. A Bitter Revolution: China's Struggle with the Modern World. (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2004). ISBN 0192803417. Follows the New Culture generation from the 1910s through the 1980s.

- Schwarcz, Vera. The Chinese Enlightenment: Intellectuals and the Legacy of the May Fourth Movement of 1919. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

- Song, Mingwei (2017). "Inventing Youth in Modern China". In Wang, David Der-wei (ed.). A New Literary History of Modern China. Harvard, Ma: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 248–253. ISBN 978-0-674-97887-4.

- Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China, Norton(1999). ISBN 0-393-97351-4.

- Spence, Jonathan D. The Gate of Heavenly Peace, Viking Penguin. (1981) ISBN 978-0140062793. Attractively written essays on the men and women who promoted intellectual revolution in modern China.