New Zealand giraffe weevil

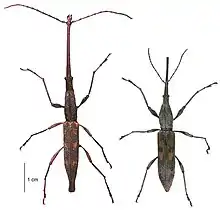

The New Zealand giraffe weevil, Lasiorhynchus barbicornis, is a distinctive straight-snouted weevil in the subfamily Brentinae, endemic to New Zealand. L. barbicornis is New Zealand's longest beetle, and shows extreme sexual dimorphism: males measure up to 90 mm, and females 50 mm, although there is an extreme range of body sizes in both sexes. In males the elongated snout (or rostrum) can be nearly as long as the body. Male giraffe weevils use this long rostrum to battle over females, although small males can avoid conflict and 'sneak' in to mate with females, sometimes under the noses of large males. The larval weevils tunnel into wood for at least two years before emerging, and live for only a few weeks as adults.

| Lasiorhynchus barbicornis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male and female New Zealand giraffe weevil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | Lasiorhynchus |

| Species: | L. barbicornis |

| Binomial name | |

| Lasiorhynchus barbicornis (Fabricius, 1775) | |

Taxonomy

This species was described by the Danish entomologist Johan Christian Fabricius in 1775, from specimens collected by Joseph Banks in 1769 on Cook's first voyage to New Zealand, presumably from Ship Cove in Queen Charlotte Sound.[1][2] Fabricius described the smaller females as a different species, Curculio assimilis, but suspected they were the males of what he named Curculio barbicornis (later moved to its own genus, Lasiorhynchus). His specimens are now in the Banks Collection of the Natural History Museum, London, and the Fabricius Collection in the Natural History Museum of Denmark.[2]

L. barbicornis is occasionally accused of not being a weevil at all,[3][4] but it fact it is in the family Brentidae, the straight-snouted weevils, as opposed to the much larger family Curculionidae or "true" weevils; brentids lack the distinctive geniculate (elbowed) antennae that characterise curculionid weevils. These and several other families are part of the superfamily of all weevils, Curculionoidea. L. barbicornis is the only member of the Brentinae (a tropical subfamily) in New Zealand, and its closest relatives are in Sulawesi, Australia, Vanuatu, and Fiji.[1] It is the only member of the genus Lasiorhynchus.

Etymology

Lasiorhynchus means "densely hairy rostrum"; barbicornis ("bearded horn") refers to the dense black backward-directed beard underneath the male's rostrum, or possibly to its hairy antennae.[1] The beetle's Māori names include pepeke nguturoa ("long-beaked beetle": ngutu roa is another name for kiwi[5]), tūwhaipapa, and tūwhaitara, the latter two after the Māori god of newly made canoes, because its canoe-like body and upturned rostrum resemble a waka and prow.[6][1]

Description

Giraffe weevils have a distinctive elongated head, and reddish-brown markings on their elytra. They are the only weevils in the world with a visible scutellum.[1]

They are New Zealand's longest native beetle,[3] and have been identified as the longest brentid weevil in the world by researchers Christina. J. Painting and Gregory I. Holwell.[7] They vary enormously in size, from 15 to 90 mm total length in males and 12–50 mm in females.[8] This wide variation in body size, particularly in the length of the male rostrum, may be in response to changing environmental conditions from year to year.[9] Body size increases the further south the weevils live, but male rostra get proportionately less long with increasing latitude.[8]

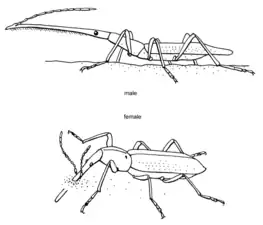

These weevils display extreme sexual dimorphism; males have an elongated rostrum or snout with antennae at the tip, which they use as a weapon for fighting over females. The female giraffe weevil has a shorter rostrum with antennae about halfway along, which allows her to bite egg-laying holes in tree trunks without damaging her antennae.[6]

Giraffe weevils are mostly active by day, sheltering in the canopy at night, and feed on sap.[10] When suddenly disturbed, they will drop backwards off a tree trunk and lie in the leaf litter, playing dead, for up to an hour.[10]

Life cycle

Eggs are laid on dying wood from October to March.[6][11] The female bores a narrow hole with her mandibles into the trunk, pulling her head out every half-millimetre to clear away sawdust. During this time the male mates with and guards her, and helps her disengage with the hole if she gets stuck.[12] The hole is usually 0.5 mm wide, 3–4 mm deep, and at a 45° angle to the trunk of the tree.[13] When finished, she lays a single egg in the hole, which is then refilled with sawdust and hidden with bark fragments.[12] The whole process takes around 30 minutes.[13]

| External video | |

|---|---|

Fighting frequently occurs if a single male comes across a mating pair: the single male will attempt to dislodge the mating male by raking his mandibles across the back of his rival, or grasping his opponent's leg with his mandibles (this is possibly the reason some males have missing leg sections.)[13] The fight then escalates to grappling, where the males engage side by side and try to push each other off the tree with their rostra.[14] Small males (under 30 mm) are less able to compete with large males, and often retreat rather than fight.[13][15] Small males, though, will readily fight with smaller or equal-sized males.[15] They can also find success by mating while the larger males are distracted by fighting; these 'sneaking' males will flatten themselves alongside or underneath females in order to avoid detection by a larger male. Due to these varied mating tactics, mating success is independent of male size.[15][16]

Because female giraffe weevils can mate multiple times before they lay their eggs, sperm competition is likely to be an important factor in determining which males get to reproduce.[17]

L. barbicornis larvae live at least two years.[10] Dissections of larvae show they feed on fungus growing in the larval tunnels, not the wood itself.[18] During the pupal stage, the weevil's rostrum is doubled underneath the body, but it straightens when the adult beetle emerges and eats its way out of the tree, leaving a square tunnel.[19] Sometimes the tunnel is too narrow, and the adults perish with their rostrum protruding.[18] Adults emerge between October and March; their peak abundance is in February.[20] The sex ratio is about 60:40 males:females.[20] Adult giraffe weevils generally only live for a few weeks, although one male was recorded as living at least 29 days.[13]

Distribution and habitat

Giraffe weevils are common in the North Island, and, although rarer, are found in the northwestern South Island as far south as Greymouth.[1] One has been recorded from the Hollyford Valley in Fiordland.[21] Mitochondrial DNA suggests that during the Pleistocene ice ages giraffe weevils were only found in the remnant forests of Northland, and have expanded southward during this current interglacial.[22]

They are found in native forest, mainly at lower altitudes.[6] Their larvae inhabit at least 17 species of native trees, including lacebark, pigeonwood, rewarewa, tawa, pukatea and rimu, but are especially common on karaka and mahoe.[10]

References

- Kuschel, G. (2003). Nemonychidae, Belidae, Brentidae: (Insecta: Coleoptera: Curculionoidea). Fauna of New Zealand. Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand: Manaaki Whenua Press. ISBN 978-0-478-09348-3.

- Kuschel, G (1970). "New Zealand Curculionoidea from Captain Cook's voyages (Coleoptera)". New Zealand Journal of Science. 13: 191–205. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Gibbs, George (8 July 2013). "Insects – overview - In the bush". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Toki, Nicola (30 July 2012). "See no weevil…". Stuff. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- "kiwi - Māori Dictionary". maoridictionary.co.nz. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- Crowe, Andrew (2002). Which New Zealand Insect?. North Shore: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780141006369.

- Painting, Christina J.; Holwell, Gregory I. (2013). "Exaggerated Trait Allometry, Compensation and Trade-Offs in the New Zealand Giraffe Weevil (Lasiorhynchus barbicornis)". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e82467. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...882467P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082467. PMC 3842246. PMID 24312425.

- Painting, C. J.; Buckley, T. R.; Holwell, G. I. (2014). "Weapon allometry varies with latitude in the New Zealand giraffe weevil". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 27 (12): 2864–2870. doi:10.1111/jeb.12517. PMID 25303121. S2CID 12337432.

- Painting, Christina J.; Holwell, Gregory I. (2015). "Temporal variation in body size and weapon allometry in the New Zealand giraffe weevil". Ecological Entomology. 40 (4): 486–489. doi:10.1111/een.12199. S2CID 83748914.

- Painting, C. J.; Holwell, G. I. (2014). "Observations on the ecology and behaviour of the New Zealand giraffe weevil (Lasiorhynchus barbicornis)". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 41 (2): 147–153. doi:10.1080/03014223.2013.854816. S2CID 84193298.

- Reekie, Steve. "Giraffe Weevil". Trek Nature. Trek Nature. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Lindsay, Terrence; Morris, Rod (2000). Collins Field Guide to New Zealand Wildlife. Auckland: HarperCollins. ISBN 9781869508814.

- Meads, M.J. (1976). "Some Observations on Lasiorhynchus barbicornis (Brentidae: Coleoptera)" (PDF). New Zealand Entomologist. 6 (2): 171–176. doi:10.1080/00779962.1976.9722234. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Painting, Christina J.; Holwell, Gregory I. (2014). "Exaggerated rostra as weapons and the competitive assessment strategy of male giraffe weevils". Behavioral Ecology. 25 (5): 1223–1232. doi:10.1093/beheco/aru119.

- Painting, C.J.; Holwell, G.I. (2014). "Flexible alternative mating tactics by New Zealand giraffe weevils" (PDF). Behavioral Ecology. 25 (6): 1409–1416. doi:10.1093/beheco/aru140. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- "Male giraffe weevils battle it out for female's affections". ONE News Now. TVNZ. 27 August 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Painting, Chrissie (31 March 2016). "Autumn fun with giraffe weevils". Chrissie Painting, Behavioural Ecologist. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- May, Brenda M. (1993). Larvae of Curculionoidea (Insecta: Coleoptera): a systematic overview. Fauna of New Zealand. Lincoln, New Zealand: Manaaki Whenua Press. ISBN 978-0-478-04505-5.

- Miller, David (1971). Common Insects in New Zealand. Wellington: A. H. & A. W. Reed. p. 79.

- Painting, Christina J.; Buckley, Thomas R.; Holwell, Gregory I (2014). "Male-biased sexual size dimorphism and sex ratio in the New Zealand Giraffe Weevil, Lasiorhynchus barbicornis (Fabricius, 1775) (Coleoptera: Brentidae)". Austral Entomology. 53 (3): 317–327. doi:10.1111/aen.12080. S2CID 83861032.

- Shields, Morgan (2013). "The most southern specimen of the Giraffe Weevil Lasiorhynchus barbicornis (Curculionidae; Brentidae; Brentinae) found in the Hollyford Valley, Fiordland". The Weta. 46 (1): 44–45.

- Painting, Christina J.; Myers, Shelley; Holwell, Gregory I.; Buckley, Thomas R. (2017). "Phylogeography of the New Zealand giraffe weevil Lasiorhynchus barbicornis (Coleoptera: Brentidae): a comparison of biogeographic boundaries". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. XX: 13–28. doi:10.1093/biolinnean/blx051.

External links

- Lasiorhynchus barbicornis discussed on RNZ Critter of the Week, 24 March 2016

- Reproductive behaviour of New Zealand giraffe weevils discussed on RadioNZ, Summer Days with Jesse Mulligan, 3 January 2017

- Facsimile description of this species in Fabricius' Systema Entomologiae (in Latin)