Newmarket Canal

The Newmarket Canal, officially known but rarely referred to as the Holland River Division, is an abandoned barge canal project in Newmarket, Ontario. With a total length of about 10 miles (16 km), it was supposed to connect the town to the Trent–Severn Waterway via the East Holland River and Lake Simcoe. Construction was almost complete when work was abandoned, and the three completed pound Locks, a swing bridge and a turning basin remain largely intact to this day.

The project was originally presented as a way to avoid paying increasing rates on the Northern Railway of Canada, which threatened to make business in Newmarket uncompetitive. The economic arguments for the canal were highly debatable, as the exit of the Waterway in Trenton was over 170 kilometres (110 mi) east of Toronto, while Newmarket was only 50 kilometres (31 mi) north of the city. Moreover, predicted traffic was very low, perhaps 60 tons a day in total, enough to fill two or three barges at most.

From the start, the real impetus for the project was a way to bring federal money to the riding of York North, which was held by powerful Liberal member William Mulock. That it was a patronage project was clear to all, and it was under constant attack in the press and the House of Commons. As construction started in 1908, measurements showed there was too little water to keep the system operating at a reasonable rate through the summer months. From then on it was heaped with scorn in the press and became the butt of jokes and nicknames, including "Mulock's Madness".[1]

The canal was one of the many examples of what the Conservative Party of Canada characterized as out-of-control spending on the part of the ruling Liberals. Their success in the 1911 federal election brought Robert Borden to power and changes at the top of the Department of Railways and Canals. They quickly placed a hold on ongoing construction, and a few weeks later, ended construction outright. Today, locals refer to it as "The Ghost Canal".[2]

History

Previous water transport

The East Holland River running through Newmarket had long been used as the eastern branch of the Toronto Carrying-Place Trail, running from Lake Ontario to Lake Simcoe and then on to Georgian Bay. Its location on this route led to the founding of the townsite on the bank of the river in 1796.[3]

Traffic on this section led William Roe and Andrew Borland to set up a fur trading post under a huge elm tree on the bank of the river at the ending of the War of 1812. The two spread the word that they would be trading at that site, saving trappers the need to travel all the way to York (Toronto) to sell their goods. This "new market" gave its name to the town. Borland moved on, but Roe stayed in town and set up a new store at the south end of what developed into Main Street, complete with a dock on the river for traders to use.[4]

Shortly thereafter, initial planning began for a Toronto and Georgian Bay Canal that would end on the Humber River in Toronto. The Humber spreads out across a wide area north of the city, including the hills south of Newmarket. Kivas Tully's team selected a route somewhat further to the west closer to Bond Head. The plans later reemerged as the Huron and Ontario Ship Canal, but remained dormant.[3]

Concept

The town of Newmarket had undergone rapid growth before the start of the 20th century due largely to the efforts of William Mulock, then a sitting member of the Liberal Party of Canada and Wilfrid Laurier's right-hand man in the province. He used his influence to bring a number of industries to the town, setting up along the Northern Railway of Canada's mainline which passed northward through town along the river valley. The remains of these industries are still visible on the local geography; Joseph Hill's lumber mill and later William Cane and Sons factory's mill stock now forms Fairy Lake,[5] the Davis Leather Company's buildings today form the Tannery Mall,[6] and one of the original Office Specialty factory buildings has been converted to lofts just east of Main Street.[7][8]

The Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) took over the Northern Railway in 1888. In 1904 they raised rates from 3 cents per ton-mile to 4 cents.[lower-alpha 1] They also charged deliveries anywhere along the line the full fare to Toronto, meaning businesses further north had no pricing advantage over Toronto factories when receiving materials from further north, but still had to pay for their own goods to get that extra distance to market. This would add several thousand dollars a year to operations shipping to Toronto, and the factories in Newmarket complained that this would put them out of business. A series of depositions by business leaders from the towns along the line failed to change the GTR's mind, and alternates began to be considered.[7]

At this time the Trent–Severn was in the last stages of being constructed. It was already clear that the era of the barge canal was passing to the railway; when elimination of tolls on the Erie Canal failed to improve business, the chief engineer of New York stated that "canals as a successful and necessary means of transportation have outlived their usefulness."[10] Whether it was worth the money to complete the Trent was a matter of great debate. While it offered convenient access from Lake Simcoe to trade on the upper Great Lakes, its southern exit was still not complete, and impractically far to the east at Trenton. It was ultimately completed both for political reasons and as a way to secure water rights for hydroelectricity, the idea of using it as a shipping route was no longer important.[11]

Mulock proposed a short canal route from Holland Landing to Newmarket, with the possible extension to Aurora. South of Aurora, the Oak Ridges Moraine would make further progress difficult.[3] The usefulness of such a route was suspect, given that the northward flow of goods was limited to perhaps 20 short tons (18,000 kg) a day, compared to 40 moving south to Toronto. Although the canal would be marginally useful for imports, it would not be very useful for exporting the resulting goods back to market. Mulock invented a number of schemes to drive more traffic, including shipping oats via the Trent to the American Cereal Company (later known as Quaker Oats) in Peterborough.[12]

Mulock and the mayor of Newmarket, Howard S. Cane,[lower-alpha 2] one of the "Sons" of the local factory, met by chance on the train to Toronto in September 1904. Mulock presented his idea and Cane was enthusiastic.[lower-alpha 3] The two put up posters for a town meeting on the issue on 9 September, and in spite of the short notice, the meeting the next day drew a crowd of 300 people. The unanimous decision contained two proposals, one for the canal to Newmarket and Aurora, and a second to widen portions of the Western Holland River through today's Holland Marsh area to Schomberg, and a similar widening of the Black River south from Lake Simcoe into Sutton. The organizers then began collecting signatures on a petition to the federal government, presenting it with almost everyone's name from the entire surrounding area in January.[14]

Walsh's survey

Two weeks after the meeting, the temporary organizing company known as the Trent Valley Canal Extension,[lower-alpha 4] hired E. J. Walsh to produce a preliminary design for the canal. Walsh had been a primary engineer on the later sections of the Trent-Severn, as well as many other major construction projects across the country.[15] He was, however, still working on his own while many of his former underlings had since received appointments in the civil service. Walsh considered himself a victim of this patronage, and stated that "My engineering record is unassailable: the works successfully carried out are an uncompromising refutation of any reflection thereon" while going on to state that his superiors in the Department of Railways and Canals were "self-seeking obsequious sycophants".[16]

Mulock had leaked the news that Walsh had been hired even before the formation of the company, but Walsh did not actually arrive in Newmarket until 17 October 1904. In spite of constant pressure from Mulock, Walsh refused to hurry the survey and spent the next two months making careful measurements. Although no accurate measurement of water flow was made at that time, it was clear the supply was a major concern. This, and the lack of traffic, suggested keeping the canal as small as possible.[17]

Summoned to Ottawa in January 1905, Mulock ordered Walsh to produce an estimate by 11 January. Continuing to protest over a lack of measurements, he put the figure at $328,825.[17] This was apparently a shock to Mulock, and the cost was so high that it could not be buried in the Trent budget. This meant that Mulock would have to push the funding through Parliament as a separate project, which led to the very real possibility that it would be cancelled.[17] In response, Mulock organized a group of prominent businessmen from the Newmarket area to travel to Ottawa to meet with Laurier. They arrived on 21 February 1905 and found the Prime Minister more than interested in the project, and he noted:

...instead of asking for a post-office or cut-stone building, the first request ever made by the County of York for the expenditure of public money was for the more substantial purpose of enhancing the facilities of transportation of their people for the development of commerce.[18]

Mulock, meanwhile, began to come under fire in the House of Commons for what the Conservatives called a blatant "bribe to the electors of North York".[17] He had the Minister for Railways and Canals, Henry Emmerson, order a more complete estimate from Walsh, this time with an eye to reducing the cost as much as possible. Mulock continued to pressure Walsh to complete the estimates, and Walsh continued to stall in fear that he would be held responsible if there were any overruns.[19]

Walsh was once again summoned to Ottawa in March 1905 and told to present a new plan with costs cut as much as possible, which he only agreed to after being promised that he would not be held to them. He came up with slight modifications, replacing some of the concrete with stone-filled wooden pilings for piers and other features, and the replacement of some of the swing bridges with higher wooden ones. These changes reduced the price by $37,000, enough to cross the $300,000 threshold that might stop development. He was then instructed to begin the detailed construction planning, which he started in June. From this point, work to continue south to Aurora, as well as work on the West Holland and Black River, no longer appears in any of the plans.[19]

Political changes

Mulock had become increasingly disenchanted with the Liberal Party, and in the summer of 1905 he announced he was retiring his position owing to ill health.[lower-alpha 5] A by-election on 22 November 1905 was won by Liberal Allen Bristol Aylesworth, but with a significantly smaller majority than Mulock had enjoyed. This was a sign of a growing public shift to the Conservative party, and Aylesworth was placed in the position of having to support the canal in order to maintain Liberal support in the area. Mulock was appointed the Chief Justice of the Exchequer and remained active in politics and in the construction of the canal.[15]

In July 1905, M. J. Butler was promoted to the position of Deputy Minister and Chief Engineer of the Department of Railways and Canals.[16] Apparently there was deep personal enmity between Walsh, Mulock, Butler and Butler's friend Michael John Haney, whose connections placed Butler in the position of Chief Engineer. Butler and Haney were very much "railway men,"[15] having worked together on a number of projects in the past, and the two intensely hated Mulock and his interference in the department's work.[15] Shortly after taking office, Walsh noted that Butler had spoken "in a contemptuous manner of Sir William Mulock and the Holland River improvements, and expressed himself as thoroughly opposed."[15]

Walsh considered Butler to be an engineering nobody, and noted that the appointment, arranged by Haney, was to the great amusement of the engineering world.[20] Having little engineering background of his own, Butler came to rely heavily on Alex Joseph Grant, who had become the chief engineer on the canal projects. Grant had previously been a flagman on one of Walsh's work crews, and held a junior position during the construction of the Soulanges Canal. Walsh felt his appointment was entirely political, and he appears to have been very upset that he had not been given the position.[16]

Dredging begins, and ends

By January 1906, under intense pressure, the Department of Railways and Canals ordered Walsh to present plans for the dredging of the Holland, section 1, as soon as possible. He had originally specified this to be 4 feet (1.2 m) deep, but Butler overruled him and ordered them to be dredged to 6 feet (1.8 m), the same as the rest of the Trent system. Walsh returned the plans in the middle of February and on 18 April 1906 the dredging contract for $46,487[lower-alpha 6] was won by The Lake Simcoe Dredging Company. This company was formed primarily by E.S. Cane and Dr. Philip Spohn of the Penetanguishene Asylum for the Insane, neither of whom had any experience in dredging.[15]

By the spring the company had purchased a small scow and began building a steam-powered clamshell bucket on the end of a 100-foot-long (30 m) arm. Grant reported this uncritically to Butler in a June 1906 progress report, but Butler replied that such a long boom on such a small scow would be "a circus". They only managed to begin dredging in November and within three weeks the river froze over and work ended.[21] The company continued with their efforts when the river cleared in the spring of 1907, but by the fall they had managed to clear only 3,500 cubic yards (2,676 m3) of an estimated 270,000 cubic yards (206,430 m3). They abandoned the work, and in May 1908 the contract was "taken out of their hands."[22]

Walsh's final plans

Walsh delivered his final plans for section 2 in September 1906. It was relatively similar to the ad hoc plans presented earlier, based on the 143 by 33 feet (44 m × 10 m) lock size used across the Trent system. To address the lack of water, Walsh added large piers leading upstream from the locks, forming small lakes at the entrance to each one. These were built from 15-inch (38 cm) tamarack poles driven into the riverbanks and covered with planks. Upstream from the lock in each of the pier areas was a 10 by 6 feet (3.0 m × 1.8 m) box in the channel floor used to capture silt.[23] Three earthen dams would redirect water from local creeks into the system, and the entire system would be lined with puddle, a clay mixture widely used to line channels and canals to prevent water leakage.[23] The canal would be spanned by four bridges; two existing wooden bridges in Holland Landing would be raised, and two swing bridges would be built, one at the 2nd Concession and one at Green Lane.[24]

The biggest problem that Walsh faced, and the major reason for the delays in competing the plans, was the lack of water. To supply the required water, especially south of Fairy Lake where there were few streams; Walsh proposed using Wilcox Lake as a reservoir. Wilcox, about 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) south of Aurora, normally empties to the west, ultimately flowing into Lake Ontario via the Humber River. A dam on this outlet would raise the water level about 3 feet (0.91 m), along with the connected Lake St. George a short distance to the northeast. This would add about 150,000,000 cubic feet (4,200,000 m3) of water supply, and provide a constant flow of 66,000 cubic feet (1,900 m3) of water an hour, about double the natural flow of the Holland at Fairly Lake. of A small channel would be cut from Lake St. George to the southernmost point on the Holland, about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) due north, just north of the current Bloomington Road.[25]

Walsh estimated the total cost of section 2 to be $314,200, and the additional work on the Lake Wilcox channel at $40,315. Those figures included $2,000 for the purchase of land and rights-of-way, $1,000 of that being to move the Toronto and York Radial Railway line to avoid flooding, although he had specifically asked for this line to be moved out of the way a year earlier when it was being built.[26] The figures also included a 10% contingency, which, if removed, made the total price of the system very close to the figure of $328,000 that he had presented over a year and a half earlier.[27]

Grant's changes

When Walsh presented his plans, Butler turned them over to Grant with the instructions "to go over them carefully and make any notes."[28] Grant responded by completely redesigning the canal, making changes that appear to have no rational basis and doubling the cost. Walsh later remarked that Grant "from the confines of his office, and with the connivance of Butler, undertook and did within a few days mutilate the plans and proposals."[28] According to Angus's account, this was done deliberately to make the plan unattractive and make Walsh look foolish when the plan was cancelled, but they underestimated the amount of political support for the project.[28]

Among many changes, Grant specified concrete throughout the system, including the piers and dams, replacing any timber construction. The entire route was to be dredged deeper and wider. The locks were lengthened from 143 feet to 175 feet (53 m). The reason for this change appears to be similar changes made on the Erie Canal,[29] although they could serve no possible purpose in this case as the rest of the Trent was 143 feet and that was the only route to the Erie. The simple valve system used in the lock gates was replaced by a more complex system using piping in the lock walls, which required them to be much thicker. The two 10 foot (3.0 m) locks in Holland Landing were replaced by a single lock of 20 feet (6.1 m) rise, which meant the walls had to be much thicker to hold the increased weight of water. The cost of these thicker walls was compounded by replacing the concrete-over-puddle construction by solid concrete.[28]

The result of these changes was enormous, with the estimated cost of section 2 roughly doubled. As if this were not enough, when the original dredging efforts failed and were taken over in May 1908, Grant ordered a new survey of the Holland and came up with the plan of cutting a channel from the eastern to western branches. The western branch is deeper and wider and would require little dredging, but was some distance to the west across marshy land. His new plan more than doubled the estimated cost for section 1 from Walsh's final estimate at $48,295[lower-alpha 7] to $131,293.[22] The final report was returned to Butler on 6 December 1906.[30]

Butler sent Grant's report to Walsh, who responded to Butler in January 1907 with a scathing letter dismissing every change Grant made. He started by pointing out that Grant's desire to straighten the river was made without him ever visiting the site, and Walsh stated he would see such work was entirely unnecessary had he actually looked at the river. His reserved his strongest complaints for the changes to the locks, noting that they would "enormously increase the aggregate cost of the work, lessen the water storage for supply purposes, and substitute not the slightest benefit or advantage in any other respect."[31] He concluded that Grant's plan "appears to me illogical in view of the fact that it is based on false premises, and without regard to the nature of the Canal and its requirements, its probable present and prospective traffic, its exceptional uniqueness when compared to other canals in Canada, especially as to the question of water supply upon which the success of the whole project hinges."[32]

Walsh had designed the canal with four locks of equal size. That way when the water from one of the locks was released, it would flow downhill into the next. Water would only be lost from the system at lock 4, the last lock. But by replacing the two centre locks with one larger one, this was no longer true. For one, the opening of lock 1 in Newmarket would produce only half the water needed to fill the large lock 2, and when lock 2 was opened, the smaller lock 3 could not contain half of the water, which would have to be dumped.[32]

Butler gave the letter to Grant, who then made his own changes to address the problem of water supply. His solution was to make a reservoir out of the entire canal, replacing the original lock in Holland landing with a single enormous lock.[32][lower-alpha 8] These plans were abandoned, and the final plans submitted on 1 April 1907 show Grant's original layout, with no plan for additional water supply at all. Butler's final submission to the Department, filed on 27 April 1907, included most of Grant's suggested changes. The estimate for section 2 was placed at $596,826 and optimistically forecast to be completed by 31 March 1908.[33]

Construction begins

Contract tenders for section 2 were sent out in the spring of 1907, shortly after Emmerson had been replaced by George Perry Graham as Minister of Railways and Canals. Three tenders were received, all much higher than Grant's estimates; Larkin and Sangster of St. Catharines bid $697,302, Brown and Aylmer of Toronto bid $694,542, and John Riley at $652,009.[33] Additional contracts for concrete added $8,000, and three swing bridges added another $17,792.[34] Riley won the contract in June 1907, but failed to raise the capital needed for the construction bond of $22,000, and on 12 September wrote that he would not be continuing. In January 1908 the contract was about to be awarded to the Queenstown Quarry Company when Riley sold his contract to Willam Russel, who formed the York Construction Company in April 1908.[35]

Construction on section 2 finally began in April, mostly using Italian labour from the Toronto area. There were a few complaints on the part of locals who were expecting more local workers to be hired, and it was rumoured (but denied) that only Italians would be hired. There were a few minor labour disputes among the workers and management as well, but these did not appear to slow construction. Businesses in Newmarket did get a share of the supply work, but even catering was handled by a Toronto firm.[36] The main winners in the local area were landowners who were paid for their share of their properties that were being flooded, with total payouts being on the order of $42,000. Accusations were made that the amount paid out was based largely on political affiliation, with a number of cases being presented in which landholders were paid many times the department's own valuations.[37]

The start of construction coincided with the 1908 federal election. It was a factor in Ayleworth's ability to hold the seat, although he won it with a margin of only 306 votes.[38] About $185,000 was spent during 1908, and a similar amount was requested for 1909. When these figures were presented, opponents pointed out that Graham had been a continual opponent of the Tay Canal outside Ottawa as an expensive waste of money with dubious traffic; yet now he was supporting the Newmarket construction which had even less potential traffic and cost twice as much.[39]

Water supply problems

As early as 1905, when it became clear that the project had strong backing within the Liberal establishment and that appealing to reason was not going to work, the Conservatives switched their attacks to the problem of a lack of suitable water supply. On 12 June 1906, Sam Hughes and Albert Edward Kemp led an attack on the plans during Question Period, asking the Minister of Railways and Canals, Emmerson:

Hughes: Will the honourable minister be good enough now to give us the estimate of the supply of water in the little creek - it is merely a creek - running down there?

Emmerson: The report of the engineer is that there is an ample supply of water.

Kemp: There is not enough water supply for this canal. I do not care what engineer reports on it... there was not enough water in this stream for two or three boys to bathe in - that when they wanted to get a bath they had to make a dam and collect enough water.

Hughes: ... How many cubic feet of water per hour?

Emerson: 30420 cubic feet.

Hughes: How many cubic feet to fill the lock?

Emmerson: 28000.[40]

While Emmerson's statement about lock size was true in Walsh's original plan, Grant's changes doubled this 58,000 cubic feet (1,600 m3). This would require at least two hours to fill.[41]

Given the constant pressure in parliament, Butler instructed Grant to make a careful measure of water flow, which started in 1908. When the results were presented to parliament in 1909, they revealed an average flow of 540 cubic feet per minute, or 32,400 cubic feet (920 m3) per hour, dropping to 445 per minute (26,700 per hour) in late summer, and a peak flow in spring of 139,000 cubic feet (3,900 m3) per hour.[42] This limited the main lock to four operations per hour during the flood period, but would not even cover leakage and evaporation during the summer.[40]

Walsh's own plans to use Lake Wilcox could not be used any more because of the legal suits that would result from rerouting this water away from the Humber.[43] South of Newmarket there was simply no other suitable source of additional water, and the existing millstock in downtown Newmarket presented a difficult barrier to cross, one of the many reasons the extension to Aurora was abandoned.[40] It was around this time that someone in the Ministry[lower-alpha 9] suggested a better solution would be to install a pump at Lake Simcoe and use that to pump water uphill to a reservoir south of Newmarket. This solution was announced by the newly appointed Graham, to fresh rounds of catcalls.[43]

By this time Grant had filed additional estimates on the work, raising the total cost of the canal to $967,814, but these estimates still did not include any of the required reservoirs. When asked, he stated that "I do not know what this item will cost as no plans or estimates have yet been prepared for storage reservoirs."[42] Grant had also started looking at ways to save water in the system, introducing a second set of gates in the middle of the locks to effectively cut them in half so that smaller boats could lock with half the total water use. He returned these plans to Butler in September 1908, having also reduced their length back to 143 feet and adopted Walsh's original valve system and eliminating his own lock-side tubes. Butler rejected these changes, arguing the advantages were too small to be worthwhile.[44]

Grant continued working on the problem, and in June 1909 he came up with the plan of installing seals in the middle of the locks that would prevent downhill leakage. These would sit on the bottom of the lock and be raised using winches, held in place by an inflated India rubber bag at the top, and latches at the sides. Butler responded saying they could not be added unless savings were found elsewhere. These were found by reducing the length of the entrance piers. Butler approved these changes, but it was eventually found that the continual changes in the plans resulted in additional payments to the contractors, who were continually being forced to change plans.[45]

Continued debate

As the enormity of the water supply problem became clear, the project became the subject of continual heaps of scorn in the press. The Orillia Packet joked that the builders could dispense with the swing bridges, and people could cross it by simply putting on their rubber boots.[46] Samuel Simpson Sharpe quoted newspapers stating that it was "a canal on which nothing but votes will be floated."[47] The News and Telegram ran a cartoon showing Aylesworth and Graham operating a hand pump to fill a dry ditch.[48]

Things were no better in the House of Commons of Canada.[40] Haughton Lennox, the longtime member for Simcoe South which included Aurora, remained staunchly opposed to the system, and repeatedly spoke out against it in the House.[49] Even Graham himself, now the Minister in charge of the construction, could not help joking about it, commenting slyly that "There is plenty of water in it for all the commerce there will ever be on it."[43]

The opposition launched a full attack on the canal in 1909. The 1908 work estimates had been buried in the roughly $1 million allocated to the Trent system as a whole, and the government was attempting to do the same for the following year as well. On 25 February, Graham was asked to separate the Newmarket work out of the rest of the estimate, which he refused to do.[48]

On 23 March, when the Minister of Finance moved that the house move to the Committee of Supply, normally a commonplace event. Thomas George Wallace opposed the motion so he could add an amendment cancelling the canal as "a wanton misuse and waste of public money." Members from Toronto and those along the main route of the Trent led the attack. The resulting debate continued well into the evening, and the Hansard records over 1,000 words on the topic in the acrimonious debate. The Liberals were just able to defeat the motion when the division bells rang.[48]

Having almost lost what turned into a motion of no confidence, Laurier contacted Mulock and asked for all information he had on everyone involved. This indicated that many of the people complaining about the canal, including Lennox, had signed their names to the original request. Mulock also suggested they raise the possibility of considerable pleasure boat traffic on the canal, but Laurier never used this line of defence. The same sort of fight occurred in 1910, as expected, when the opposition introduced a motion to reduce the allocation for the Trent by exactly the amount of the Newmarket work. The Liberals were only slightly better prepared.[50]

As he had predicted, Walsh was blamed for the problems in both debates, with various Conservatives claiming he had submitted a low estimate.[51] This was traced back to Butler; when Graham took over the office he questioned Butler about the problems, and Butler placed the blame on Walsh. Butler quit his position in January 1910, and while Graham quickly appointed Archibald Campbell as deputy minister, he left the chief engineer position open. This prompted Walsh to apply for the position, but Butler and Haney lobbied against him, convincing Graham that Walsh was a closet Conservative. With this avenue blocked, Walsh wrote to H.S. Cane on 5 April 1910, outlining the entire situation and blaming Butler for arranging the entire fiasco "to damn Sir William Mulock, the Engineer who reported favourably thereon, and the contractor of the Section No. 1."[52] ending the letter with the suggestion Cane lobby on his behalf or that he would go public with his concerns.[52]

This effort was not successful; Graham was told of Walsh's threat and W.A. Bowden was appointed chief engineer late in the year. In response, Walsh sent a 20 January 1911 letter to Graham, placing all of the blame on Butler and absolving himself.[53] When Graham attempted to bury the letter, Walsh leaked its existence to Wallace, who read it into the Hansard in July. Wallace then used it as the basis for yet another motion of non-confidence, opening with the statement:

This House reports that in many cases the government have... used and applied public moneys for the purposes what were not in the public interest.[54]

Once again the debate stretched for hours, this time with attacks against a long series of similar Liberal projects across the country, or ones that had been proposed only to be immediately cancelled when a by-election brought a Conservative to that riding. The Newmarket Canal remained the focus of the attacks throughout.[55]

Cancellation

All of the debate sparked by Wallace's motion was ultimately for nothing, as Laurier dissolved the parliament the next day on 29 July for a 21 September election. The Liberals based their campaign on the topic of reciprocity, as free trade was known at the time. The Conservatives ignored the reciprocity issues and ran a campaign centring on the Liberal's runaway spending. The Newmarket canal was front and centre in the debate, put up as an example of an out-of-control government. Aylsworth decided to retire, and did not contest his seat. The canal remained popular in the area, but not enough to keep the riding, which was won by the Conservatives in a tight race in an election that was otherwise a Conservative sweep.[55]

When Robert Borden's Conservative government came into power, he appointed Frank Cochrane to replace Graham in the Ministry of Railways and Canals. Cochrane immediately froze construction on the canal, and ordered new accounting for all of the ministry's ongoing work across the country.[55] W.A. Bowden, the new chief engineer, replied with a report on 3 January 1912, stating that about 80% of the work was complete on the main portion of the canal, but little of the dredging of the upper Holland had been carried out. He estimated traffic would be limited to pleasure boats and barges carrying wood to the factories, but the locks and bridges would have to be manned at an annual cost of $4,000, and another $4,000 to run the pumping system that had been introduced to keep the canal full. Although most of the work was complete, he estimated that they could save $393,000 if it was abandoned.[56]

The report was presented to Borden, who signed it on 5 January. Contract negotiations with the involved companies started immediately, leading to a deal in which the companies received a small lump sum for immediate cleanup of the sites, and were awarded the contract for the construction of the final locks on the Trent-Severn.[56] A delegation of businessmen from Newmarket Board of Trade sent a resolution to complete construction. It was read in Parliament on 14 February 1912, but the government ignored the plea.[57] The system was abandoned as-is, and it was not until 1924 that additional funds were provided to clean up the construction sites.[51][58]

The Holland River would, ultimately, host a canal system, but in a different location and for entirely different purposes. Starting in the 1920s, the Holland Marsh area, west of Newmarket on the western branch of the Holland River, began the construction of two large drainage canals on either side of the marsh area. These are referred to as the north and south canals.[59]

Route

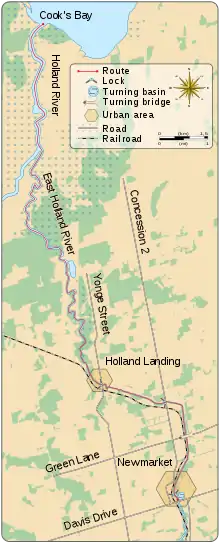

The canal route starts on the eastern arm of the Holland River, which splits off of the western arm just south of Cook's Bay. The eastern arm runs roughly southward through River Drive Park and into Holland Landing on the west side of town. At the southwestern corner of town it turns to the southeast, and after a short distance reaches the first lock, now under the bridge carrying "old" Yonge Street into town.[lower-alpha 10]

The river continues southeast for two kilometres where it reaches the second lock at Concession 2 (Bayview Avenue). Here it meets the inlet of the Rogers Reservoir, named for Timothy Rogers who settled the area, which provided a water buffer. At this point it turns south again for just over a kilometre before turning southwest into Newmarket through the third lock, which lies just north of the canal's endpoint.

The canal ended in a turning basin on the north side of Davis Drive in Newmarket, at what was then the northern end of the downtown area. The Holland River continues south from this point, with Main Street running parallel to it on the west bank, and the train line on the east bank. The city originally grew up along this north–south axis. Fairy Lake, on the southern edge of downtown, is 1 km to the south of the turning basin.

The canal route remains largely intact. The southern portion is now paralleled by the Nokiidaa Bicycle Trail from Newmarket to Holland Landing. The turning basin was filled in during the 1980s, and now forms the eastern section of the parking lot for the Tannery Mall and the associated Newmarket GO Station.[62]

The single-lane swing bridge over Green Lane was used until 2002, when it was replaced by a much larger four-lane bridge as part of the construction of the Newmarket Bypass. The original bridge structure itself was replaced by a footbridge a few years later, with the original swing mechanism relocated to one end of the new footbridge.[63] Lock #1 in Holland Landing was used as the foundations for a bridge along a new routing for Yonge Street, lock #2 was likewise used for a bridge on 2nd Concession Road, while lock #3 in Newmarket now carries the bike trail over the river.

Notes

- Angus says the rates were raised 50%, but actual numbers are not offered.[7] Williams has the actual numbers, which is a 25% increase, not 50%.[9]

- Cane is spelled Kane at one point in the Hansard. Howard was the second "H.S. Cane" to be the mayor of Newmarket, and the third Cane to do so.[13]

- The meeting on the train is the story according to Angus.[14] Williams is not specific; that account suggests the idea was Cane's and Mulock took credit for it after the fact.[9] Angus, however, suggests that Mulock had long been thinking about a canal due to his distaste of railway subsidies.[3]

- Mirroring the name of the Trent Valley Canal Association, who were instrumental in supporting the continued development of the canal system and served as an inspiration for Mulock's efforts.[7]

- Mulock lived to 1944 at the age of 101, making the ill health excuse particularly ironic.

- Angus puts the number ten dollars higher at $46,497.10.[15]

- This final estimate was slightly higher than what had earlier been agreed to when dredging started.

- The single lock is stated to be 75 feet high in Williams' account,[32] but it is not clear how this would have been possible given there is only 43 feet rise to Newmarket and the land is generally flat. Had such a lock been constructed it would have flooded both towns and much of the surrounding area as well. It is possible this is simply a typo on William's part (or one of his references), and the correct number is 45 feet, which is technically possible.

- The existing references do not record who came up with this idea.

- Yonge Street was realigned to the west in the 1960s, with the original route becoming the "old" section.

References

Citations

- Villemaire, Tom (21 August 2015). "Trent-Severn Waterway was hotly disputed". Barrie Examiner.

- Carter, Terry (2012). "The Ghost Canal". Town of Newmarket. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013.

- Angus 1998, p. 277.

- Carter, Robert Terence (2001). Stories of Newmarket: An Old Ontario Town. Dundurn. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9781459700215.

- Carter, Terry (2012). "A Brief History of the Town of Newmarket" (PDF). Town of Newmarket.

- Alessandrini, Chris (February 2015). "Swindler left Newmarket with mall that didn't work". Newmarket Historical Society.

- Angus 1998, p. 276.

- "Cops to karate have used Office Specialty buildings". Newmarket Era. 28 January 2008.

- Williams 1982, pp. 14–15.

- Toronto and Georgian Bay Ship Railway. 1888.

- Angus 1998, p. 213.

- Angus 1998, p. 278.

- Carter 1996, p. 59.

- Angus 1998, p. 279.

- Angus 1998, p. 283.

- Williams 1982, p. 18.

- Williams 1982, p. 20.

- Williams 1982, p. 23.

- Williams 1982, p. 25.

- Williams 1982, p. 19.

- Williams 1982, p. 27.

- Williams 1982, p. 36.

- Williams 1982, p. 29.

- Williams 1982, p. 31.

- Williams 1982, p. 34.

- Williams 1982, p. 32.

- Williams 1982, p. 35.

- Angus 1998, p. 284.

- Williams 1982, p. 42.

- Williams 1982, p. 37.

- Williams 1982, p. 39.

- Williams 1982, p. 41.

- Williams 1982, p. 43.

- Hansard, p. 1915.

- Williams 1982, p. 45.

- Williams 1982, pp. 45–47.

- Williams 1982, pp. 48–49.

- Angus 1998, p. 285.

- Hansard, p. 1592.

- Hansard, p. 474.

- Williams 1982, p. 33.

- Williams 1982, p. 50.

- Angus 1998, p. 286.

- Williams 1982, p. 51.

- Williams 1982, p. 52.

- Hansard, p. 1590.

- Hansard, p. 1588.

- Angus 1998, p. 287.

- Hansard, p. 1897.

- Angus 1998, p. 289.

- The Kelly Swing Bridge.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Angus 1998, p. 291.

- Angus 1998, p. 292.

- Williams 1982, p. 57.

- Angus 1998, p. 293.

- Angus 1998, p. 294.

- Carter 1996, p. 73.

- "Dredging up old tale of canal that was never finished". York Region.com. Originally published in the Newmarket Era. June 30, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- "Holland Marsh". Historica Canada.

- Williams 1982, postscript.

- Carter 2006.

- Latchford, Teresa (21 June 2017). "Chicken blood scandal, Quakers and euchre helped define Newmarket". York Region.

- Carter 2006, p. 198.

Bibliography

- Angus, James (1998). A Respectable Ditch: A History of the Trent Severn Waterway, 1833–1920. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 9780773518216.

- Carter, Robert Terence (Terry) (2006). "The Ghost Canal". Town of Newmarket. Archived from the original on 26 May 2006.

- Carter, Robert Terence (Terry) (1996). Newmarket: The Heart of York Region. Dundurn. ISBN 9781459713451.

- Williams, James Christopher Evan (1982). The Newmarket Canal, a history and interpretive plan. University of Toronto.

- House of Commons Debates, Volume 89. 1909.

External links

- Dodge, Val (April 30, 2009). "The Newmarket Canal". Dodgeville. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- Pictures