Lemba people

The Sena, Lemba, Remba, or Mwenye[1] are an ethnic group which is native to South Africa, Malawi, Mozambique and Zimbabwe of mixed Bantu and Yemeni heritage. Within South Africa, they are particularly concentrated in the Limpopo province (historically around Sekhukuneland) and the Mpumalanga province.

Sena | |

|---|---|

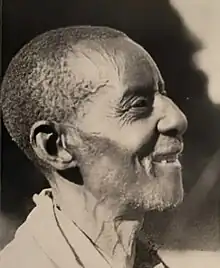

A Lemba man from the Gutu District | |

| Total population | |

| 50,000+ (estimated) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| South Africa (esp. Limpopo Province), Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe | |

| Languages | |

| Presently Venda, Karanga and Pedi | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Islam, Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Swahili, Shirazi |

Since the late twentieth century, there has been increased media and scholarly attention with regard to the Lemba's claim of common descent from Semitic people.[2][3][4] Genetic Y-DNA analyses have established a paternal Middle-Eastern origin for the majority of the Lemba population.[5][6][7]

Etymology

Tudor Parfitt has suggested that the exonym "Lemba" may originate in kilemba (most likely spread via the Mwera derivative chilemba), a Swahili word meaning turban. Thus, in context, the word "Lemba" as an ethnic identifier therefore translates to 'those who wear turbans'.[8]

Another theory is that the word Lemba may originate from lembi, a term which occurs in a number of Northeastern Bantu languages meaning a "non-African" or a "respected foreigner".[8][9] Alternatively, Magdel le Roux suggests that the name VaRemba may be translated as "the people who refuse" – probably in the context of "not eating with others" (according to one of her interviewees).[1]

In Zimbabwe and South Africa, the people prefer the name Mwenye.[10]

History

Origin

What is possibly the oldest recorded origin story[11] of the Lemba people was documented by Henri A. Junod (a Swiss-born South African missionary). In 1908, he wrote:

Some old Balemba of both the Spelonken and the Modjadji country told my informant the following legend:

- '[We] have come from a very remote place, on the other side of the sea. We were on a big boat. A terrible storm nearly destroyed us all. The boat was broken into two pieces. One half of us reached the shores of this country; the others were taken away with the second half of the boat, and we do not know where they are now. We climbed the mountains and arrived among the Banyai. There we settled, and after a time we moved southwards to the Transvaal; but we are not the Banyai.'[12]

Tudor Parfitt interprets that the legend about the destruction of the boat and the division of the tribe is perhaps a way of explaining the fact that Lemba clans are to be found in several separate locations. However, it could equally be taken as an expression of a fractured sense of identity.[13]

The original Sena was most likely located in Yemen, specifically the ancient town of Sanā (also known as Sanāw) which is located within the easternmost portion of the Hadhramaut.[2][14] In Lemba tradition, Sena has the semi-mythical status of being a sacred city of origin, and as a result, it is also the object of hopes for their eventual return.[15]

Migration into Africa

According to the Lemba oral tradition, their male ancestors migrated to Southeast Africa in order to obtain gold.[16][17]

The Lemba claim that this second group settled in Tanzania and Kenya, building what was referred to as another Sena, or "Sena II". Others supposedly settled in Malawi, where their descendants reside today. Some settled in Mozambique, eventually migrating to Zimbabwe and South Africa. They claim that their ancestors constructed Great Zimbabwe, now preserved as a monument. Ken Mufuka, a Zimbabwean archaeologist, believes that either the Lemba or the Venda may have participated in this architectural project but he does not believe that they were solely responsible for its completion. Writer Tudor Parfitt and Magdel le Roux think that they may have helped construct the massive city.[18][19] (see below). But, most academics who are experts in this field believe that the construction of the enclosure at Great Zimbabwe is largely attributable to the ancestors of the Shona, who were the first people to displace the indigenous San people from the region.[20][21][22] Such works were typical of their ancestral civilizations.[20][23][24][25]

Religion

Whilst most Lemba are Christians, there is also a sizeable minority of Lemba who are Muslims.[26] Edith Bruder wrote that "from a theological point of view, the Lemba’s customs and rituals reveal religious pluralism and interdependence of these various practices" and see membership of these religions "in cultural rather than religious terms. These apparently religious identities do not prevent them from declaring themselves Jews through religious practice and ethnic identification."[27] In 1992, Parfitt pointed to the strong cultural component in Lemba identification with Judaism.[28] In 2002, Parfitt wrote that "Those Lemba, who perceive themselves as ethnically Jewish, find no contradiction in regularly attending a Christian Church. By and large the Lemba who are most stridently 'Jewish' are often those with the closest Christian attachments."[10]

Halakhic status as Jews

In Orthodox Judaism Halakhic Jewish status is determined by documenting an unbroken matrilineal line of descent and when no such line of descent exists, it is determined by conversion to Judaism. Jews who adhere to Orthodox or Conservative rabbinism believe that "Jewish status by birth" is only passed from a Jewish female to her children (if she herself is a Jew by birth or a Jew by conversion to Judaism) regardless of the Jewish status of the father. Because of the absence of matrilineal Jewish descent for the Lemba, Orthodox or Conservative Judaism would not recognise them as 'Halakhically Jewish.' The Lemba would need to complete a formal conversion process in order to be accepted as Jews.[29]

The Reform and Reconstructionist denominations,[29] the Karaites, and Haymanot Jews all recognize patrilineage. As more is learned about the widespread history of the Jewish people, the Reform branch of Judaism has acknowledged the existence of an unusual line of descent outside the European and indigenous Middle Eastern Jewish spheres. Especially since the publication of the genetic results of the Lemba, American Jewish communities have reached out to the people, offering assistance, sending books on Judaism and related study materials, and initiating ties in order to teach the Lemba about Rabbinic Judaism. So far, few Lemba have converted to Rabbinic Judaism.

South African Jews of European descent have long been aware of the Lemba, but they have never accepted them as Jews or thought of them as more than an "intriguing curiosity."[9] Generally, the Lemba have not been accepted as Jews because of their lack of matrilineal descent. Several rabbis and Jewish associations support their recognition as descendants of the "Lost Tribes of Israel".[9] In the 2000s, the Lemba Cultural Association approached the South African Jewish Board of Deputies, asking for the Lemba to be recognized as Jews by the Jewish community. The Lemba Association complained that "we like many non-European Jews are simply the victims of racism at the hands of the European Jewish establishment worldwide". They threatened to start a campaign to "protest and ultimately destroy 'Jewish apartheid'".[9]

In Apartheid South Africa the Lemba were not recognized as an ethnic group which was distinct from other black South Africans.[30] The Lemba Cultural Association face misconceptions about their goals such as the idea that the Lemba identify more with European Judaism, only aim to affiliate with the European Jewry and not other black Jews, and are distanced from South African politics.[30] However, while the Lemba do identify with their religious Judaism, many practice Christianity as well.[30]

According to Gideon Shimoni in his book, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa (2003): "In terms of halakha the Lemba are not at all comparable to the Falasha [of Ethiopia]. As a group they have no conceivable status in Judaism."[9]

Rabbi Bernhard of South Africa has stated that the only way for a member of the Lemba tribe to be recognised as a Jew is to undergo the formal Halakhic conversion process. After that, the person "would be welcomed with open arms."[9]

As of 2015 the Lemba were building their first synagogue in Mapakomhere, in Masvingo District.[31]

Islamic and Jewish links

Many pre-modern Lemba beliefs and practices can be tentatively linked to Abrahamic religions. Ebrahim Moosa wrote that "Historians of religion have found among the Lemba certain religious and cultural practices which unmistakably resemble Islamic rituals, and there are reflections of Arabic in their language."[32] In the period in which Jews were settled in Southern Arabia, they were proselytizing, and as a result, they attracted converts from around the Mediterranean and North Africa.[10]

According to Rudo Mathivha, a Lemba of South Africa,[4] practices and beliefs which are related to Judaism include the following:

- They observe Shabbat.

- They praise Nwali (a deity) for looking after the Lemba, and they identify themselves as part of the chosen people.

- They teach their children to honour their mothers and fathers. (This is common to many ethnicities and religions.)

- They refrain from eating pig and other beasts which are forbidden by the Torah, and they forbid certain combinations of permitted foods.

- They practice ritual animal slaughter and ritual preparation of meat for consumption, a Middle Eastern practice rather than one which is common to African ethnicities.[33]

- They practice male circumcision; according to Junod's work in 1927,[34] surrounding tribes regarded the Lemba as the masters and originators of that practice.

- Since the late 20th century and due to an increasing amount of interest in their possible Jewish ancestry, they have placed Stars of David on their tombstones.

- Lemba are discouraged from marrying non-Lemba.

According to Magdel le Roux, the Lemba have a rite of sacrifice called the "Pesah", which seems to be similar to the Jewish Pesach or Passover.[35]

Some of these practices and traditions are not exclusively Jewish; they are common to Muslims in the Middle East and Africa, and they are also common to other African tribes and other non-African peoples. In the late 1930s, W. D. Hammond-Tooke wrote a book in which he identified Lemba practices that are similar to those of Muslim Arabs: for instance, their practice of endogamy codified by Muslims and Jews, as are certain dietary restrictions. Together with the similarities between many Lemba clan-names and known Arabic and Semitic words; e.g., Sadiki, Hasane, Hamisi, Haji (also Hadji [36]), Bakali, Sharifo and Saidi, Hammond-Tooke concluded that the Lemba were partially descended from Muslim Arabs.[16]

In the late 20th century, the British scholar Tudor Parfitt, an expert on marginalized Jewish groups, became involved in researching the Lemba's claims. He helped trace the origin of their ancestors back to Senna, an ancient city which they believe was located on the Arabian peninsula, in present-day Yemen. In an interview which was featured on NOVA in 2000, Parfitt said he was struck by the Lemba's maintenance of rituals which seemed Jewish and/or Semitic:

The other thing was the extraordinary importance they placed upon ritual slaughter of animals, which is not an African thing at all. Of course, it's Islamic as well as Judaic, but it's certainly from the Middle East, it's not African. And the fact that every lad was given a knife with which he did his ritual throughout his life and took to his grave. That seemed to me to be remarkably, tangibly Semitic Middle Eastern.[33]

In a 1931 article H.A. Stayt described them as an Arabic-Bantu tribe with Armenoid features, with on average, longer and thinner faces than that of the average bantu, their lips are thinner, their noses longer and more aquiline and their eyes smaller, darker and deeper-set. He stated that "there can be no doubt that the BaLemba are indeed the descendants of these Arab traders who took wives from the races among whom they traded..."[12]

Culture

The Lemba follow strict endogamous marriage practices, discouraging unions between Lemba and non-Lemba; mostly against tribes they live amongst (which they collectively refer to as Senji). Endogamy is also common among many groups.

The restrictions on intermarriages between Lemba and non-Lemba make it nearly impossible for a male non-Lemba to become a member of the Lemba. Lemba men who marry non-Lemba women are expelled from the community unless the women agree to live in accordance with Lemba traditions. A woman who marries a Lemba man must learn about the Lemba religion and practice it, follow Lemba dietary rules, and practice other Lemba customs. The woman may not bring any cooking utensils from her previous home into the Lemba man's home. Initially, the woman may have to shave her head. Their children must be brought up as Lemba.[4] If the Lemba had Jewish ancestors, the shaving of a non-Lemba woman's head may have been one of a series of rituals which were originally associated with the conversion of the first Lemba women to Judaism, this would have been the way in which Jewish males acquired women for the purpose of making families. The genetic MtDNA data of the Lemba (see below) has not shown any descent from female Jewish ancestors.

According to Tooke, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Lemba were highly esteemed for their mining and metalwork skills by the surrounding tribes which lived in the Zoutpansberg region of South Africa. He wrote in his 1937 book that the other tribes considered the Lemba outsiders.[16][17] According to articles which were written during the early 1930s, in the 1920s, the Lembas' medical knowledge earned them respect among tribes in South Africa.[37][38] Parfitt claims that colonial Europeans had their own reasons for considering some tribes rather than other tribes indigenous to Africa, because they made the British believe that they had a right to be on the continent just like other migrants.[10] Modern Y-DNA evidence confirms the extra-African origin of some of the Lemba's male ancestors. By contrast, the lead anthropologist in Zimbabwe firmly places them among African peoples, ignoring the DNA evidence.[39]

Sacred ngoma

Lemba tradition tells of a sacred object, the ngoma lungundu or the "drum that thunders", which they brought from the place which was called Sena. Their oral history claims that the ngoma was the biblical Ark of the Covenant which was made by Moses.[40] Parfitt, a professor at SOAS, University of London, wrote a book in 2008, The Lost Ark of the Covenant about the rediscovery of this object.[41] His book was adapted into a television documentary that aired on the History Channel, tracing the Lemba's claim that the ngoma lungunda was the legendary Ark of the Covenant. Following the lead of eighth-century accounts of the Ark in Arabia, Parfitt learned of a ghost town which was named Sena in the Hadhramaut.[42]

Parfitt has suggested that the ngoma was related to the Ark of the Covenant, lost in Jerusalem after the city's destruction by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II in 587 BC.[42] He believes that the ngoma is a descendant of the biblical Ark, which may have been destroyed or may have been repaired when more material was added to it as the artifact began to wear out. He says that the ark/ngoma was carried to Africa by its priestly guardians. The Lemba people's oral history claims that the Ark exploded 700 years ago,[43] and was rebuilt on its remains.[44][45]

Parfitt believes that he discovered the ngoma in a Harare, Zimbabwe museum in 2007. It had last been exhibited in 1949 by colonial officials in Bulawayo. They took it to Harare for protection during the struggle for independence, and it was later misplaced inside the museum.[46][40] Parfitt said he believed that the ngoma was the oldest wooden artifact in Zimbabwe. In February 2010, the 'Lemba ngoma lungundu' was put on display in the museum, along with a celebration of both its history and the history of the Lemba.[46]

Parfitt says that the ngoma/ark was carried into battles. If it broke apart, it was rebuilt. The ngoma, he says, was possibly built from the remains of the original Ark. "So it's the closest descendant of the Ark that we know of," Parfitt says. "Many people say that the story is far-fetched, but the oral traditions of the Lemba have been backed up by science", he said.[40] The ngoma was on display in the Zimbabwe Museum of Human Sciences, but in 2008, it disappeared. The story of Parfitt and the ngoma was updated in 2014 in the ZDF documentary "Tudor Parfitt and the Lost Tribe of Israel"[47]

The Lemba did not touch the ngoma because they considered it an intensely sacred object. It was carried by poles which were inserted into rings which were attached to each side of the ngoma. The only members of the tribe who were permitted to approach it were the male members of its hereditary priesthood because it was their responsibility to guard it. Other Lemba feared that if they ever touched it, they would be "struck down by the fire of God" which would erupt from the object. The Lemba continue to regard the ngoma as the sacred Ark.[48]

Genetics

Uniparental DNA

According to Y chromosome studies by Amanda B. Spurdle & Trefor Jenkins (1996), Mark G. Thomas et al. (2000), Himla Soodyall (2013), The Lemba are paternally most closely related to Semitic speaking populations in Western Asia (Haplogroup J = 51.7%); Central and Southern Asians (LT,K,R,F = 24.5%); with minor contributions from Bantu speaking males.[49][50][6]

A study which was conducted by Himla Soodyall (2013) observed that the non-African Y component in the Lemba is around 73.7% to 79.6%. Overall, the study shows that Y chromosomes which are typically linked to Jewish ancestry were not detected through higher resolution analysis. It seems more likely that Arab traders, who are known to have established long-distance trade networks which stretched thousands of kilometers along the western rim of the Indian Ocean, from Sofala in the south to the Red Sea in the north and beyond, to the Hadramut, to India, and even to China from about 900 AD, are more likely linked with the ancestry of the non-African founding males of the Lemba/Remba.[6]

In order to more specifically define the Lemba people's origins, Parfitt and other researchers conducted a larger study in order to compare additional Lemba subjects (whose clans were recorded) with males from South Arabia and Africa, as well as Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews.[51] They found that significant similarities exist between the markers of the Lemba and the markers of the men of the Ḥaḍramawt in Yemen. They also learned that the population of Sena, Yemen was relatively recent, so its members and the Lemba would not have shared common ancestors.[51]

A subsequent study which was conducted in 2000 revealed that a substantial number of Lemba men carry a particular haplotype of the Y-chromosome which is known as the Cohen modal haplotype (CMH), as well as a haplogroup of Y-DNA Haplogroup J which is found in some Jews, as well as in other populations which live across the Middle East and Arabia.[50][52] The genetic studies have found no Semitic female contribution to the Lemba gene pool.[53]

Among Jews, the CMH marker is most prevalent in Kohanim, or hereditary priests. As recounted in Lemba oral tradition, members of the Buba clan "had a leadership role in bringing the Lemba out of Israel".[54] The genetic study found that 50% of the males in the Buba clan had the Cohen marker, a proportion which is higher than that which is found in the general Jewish population.[55] More recently, Mendez et al. (2011) observed that a moderately high frequency of the studied Lemba samples carried Y-DNA Haplogroup T, which is also considered to be of Near Eastern origin. The Lemba T carriers exclusively belonged to T1b, which is rare and was not sampled in indigenous Jews of either the Near East or North Africa. T1b has been observed in low frequencies in Ashkenazi Jews as well as in a few Levantine populations.[56]

A 2014 article which analyzed earlier research which attempted to trace Jewish ancestry in general states:

In conclusion, while the observed distribution of sub-clades of haplotypes at mitochondrial and Y chromosome non-recombinant genomes might be compatible with founder events in recent times at the origin of Jewish groups as Cohenite, Levite, Ashkenazite, the overall substantial polyphyletism as well as their systematic occurrence in non-Jewish groups highlights the lack of support for using them either as markers of Jewish ancestry or biblical tales.[7]

In a 2016 publication, Himla Soodyall and Jennifer G. R Kromberg state that:

When blood groups and serum protein markers were used, the Lemba were indistinguishable from the neighbors among whom they lived; the same was true for mitochondrial DNA which represented the input of females in their gene pool. However, the Y chromosomes, which represented their history through male contributions, showed the link to non-African ancestors. When trying to elucidate the most likely geographic region of origin of the non-African Y chromosomes in the Lemba, the best that could be done was to narrow it to the Middle Eastern region. While no evidence of the extended CMH 11 was found in the higher resolution study, CMH however, was present at a rate of 8.8% being one mutational step away from the extended form.[57]

Representation in other media

- Channel Four documentary based on Parfitt's Journey to the Vanished City (1992 first edition).

- PBS Nova documentary: Lost Tribes of Israel, includes content about the Lemba.[58] Website includes transcript of an interview with Tudor Parfitt based on his work with them.[15]

- William Rasdell, a researcher, photographer, and visual artist developed the JAD photographic field study that outfits Lemba people of Zimbabwe with a point-and-shoot camera to document aspects of their daily lives.[59]

See also

Notes

- le Roux, Magdel (1997). "AFRICAN" JEWS" FOR JESUS A preliminary investigation into the Semitic origins and missionary initiatives of some Lemba communities in southern Africa". Missionalia. Vol. 25. pp. 493–510.

- Parfitt, Tudor (1993/2000) Journey to the Vanished City: the Search for a Lost Tribe of Israel, New York: Random House (2nd edition)

- Parfitt(2002), "The Lemba", p. 39

- Wuriga, Rabson (1999) "The Story of a Lemba Philosopher and His People", Kulanu 6(2): pp.1,11–12 Archived 16 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Spurdle, AB; Jenkins, T (November 1996), "The origins of the Lemba "Black Jews" of southern Africa: evidence from p12F2 and other Y-chromosome markers.", Am. J. Hum. Genet., 59 (5): 1126–33, PMC 1914832, PMID 8900243

- Soodyal, H (2013). "Lemba origins revisited: Tracing the ancestry of Y chromosomes in South African and Zimbabwean Lemba". South African Medical Journal. 103 (12). Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Tofanelli Sergio, Taglioli Luca, Bertoncini Stefania, Francalacci Paolo, Klyosov Anatole, Pagani Luca, "Mitochondrial and Y chromosome haplotype motifs as diagnostic markers of Jewish ancestry: a reconsideration", Frontiers in Genetics Volume 5, 2014, DOI=10.3389/fgene.2014.00384

- Parfitt, Tudor (1992) Journey to the Vanished City: the Search for a Lost Tribe of Israel.see the full explanatory note on p. 263.

- Shimoni, Gideon (2003). Community and Conscience: the Jews in Apartheid South Africa. United States of America: Brandeis University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-58465-329-5. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Parfitt, Tudor. (2002), "The Lemba: An African Judaising Tribe", in Judaising Movements: Studies in the Margins of Judaism, edited by Parfitt, Tudor and Trevisan-Semi, E., London: Routledge Curzon, pp. 42–43

- Beattie, Benedict. Lemba identity and the shifting categories of race and religion in Southern Africa. p. 95. OCLC 1356860044.

- Stayt, H. A. (1931). "Notes on the Balemba". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 61: 231–238. doi:10.2307/2843832. ISSN 0307-3114. JSTOR 2843832.

- Parfitt, Tudor (2002). "Genes, Religion, and History: The Creation of a Discourse of Origin Among a Judaizing African Tribe". Jurimetrics. 42 (2): 209–219. ISSN 0897-1277. JSTOR 29762754.

- Lost Tribes of Israel, NOVA Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), 22 February 2000

- "Tudor Parfitt's Remarkable Quest", NOVA: Lost Tribes of Israel, PBS, 22 February 2000, accessed 26 February 2008

- Hammond Tooke, W.D. (1974). The Bantu-speaking Peoples of Southern Africa. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. pp. 81–84, 115–116.

- van Warmelo, N.J. (1966). "Zur Sprache und Herkunft der Lemba". Hamburger Beiträge zur Afrika-Kunde. Deutsches Institut für Afrika-Forschung. 5: 273, 281–282.

- Parfitt, Tudor (2000). Journey to the Vanished City. New York: Vintage (Random House). pp. 1–2.

- le Roux, Magdel (2003). The Lemba – A Lost Tribe of Israel in Southern Africa?. Pretoria: University of South Africa. pp. 25, 169.

- "Great Zimbabwe (11th–15th Century)". The Metropolitan Museum of Art - Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays. MetPublications.

- Beach, D. N. (1994). A Zimbabwean past: Shona dynastic histories and oral traditions.

- Nelson, Jo (2019). Historium. Big Picture Press. p. 10.

- Pwiti, Gilbert (1996). Continuity and change: an archaeological study of farming communities in northern Zimbabwe AD 500–1700. Studies in African Archaeology, No.13, Department of Archaeology, Uppsala University, Uppsala:.

- Ndoro, W., and Pwiti, G. (1997). Marketing the past: The Shona village at Great Zimbabwe. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 2(3): 3–8.

- Pikirayi, Innocent (2001). The Zimbabwe culture: origins and decline of southern Zambezian states. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7591-0091-6.

- Mandivenga, Ephraim (1 January 1989). "The History and 'Re-Conversion' of the Varemba of Zimbabwe". Journal of Religion in Africa. 19 (2): 98–124. doi:10.1163/157006689X00134. ISSN 1570-0666.

- Bruder, Edith (2008). The Black Jews of Africa: History, Religion, Identity. Oxford University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0195333565. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- Parfitt, Tudor (1992) Journey to the Vanished City: the Search for a Lost Tribe of IsraelLondon: Hodder and Stoughton.

- "Patrilineal descent", Jewish Virtual Library

- TAMARKIN, NOAH (2011). "Religion as Race, Recognition as Democracy: Lemba "Black Jews" in South Africa". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 637: 148–164. doi:10.1177/0002716211407702. JSTOR 41328571. S2CID 143763785.

- Cengel, Katya (24 May 2015). "Zimbabwe's Lemba Build Their First Synagogue | Al Jazeera America". America.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- Ebrahim Moosa (1995). Prozesky, Martin; De Gruchy, John W. (eds.). Living Faiths in South Africa. David Philip. p. 130. ISBN 978-0864862532. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- Tudor Parfitt' Remarkable Quest, NOVA, PBS, 22 February 2000, accessed 10 May 2013

- Junod, H.A. (1927). The Life of a South African Tribe, vol. I: Social Life. London: Macmillan. pp. 72–73, 94.

- le Roux, Magdel (2003). The Lemba – A Lost Tribe of Israel in Southern Africa?. Pretoria: University of South Africa. pp. 174, 293.

- Deysel, L. C. F. "King Lists and Genealogies in the Hebrew Bible and in Southern Africa" (PDF). Old Testament Essay (OTE). 22 (3): 569. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- Trevor, Tudor G. (December 1930). "Some Observations on the Relics of Pre-European Culture in Rhodesia and South Africa". J. Royal Anthropological Inst. Of Great Britain and Ireland. 60: 389–399. doi:10.2307/2843783. JSTOR 2843783.

- Jaques, Rev. A.A. (1931). "Notes on the Lemba Tribe of the Northern Transvaal". Anthropos. XXVI (1/2): 245–251. JSTOR 40446148.

- Parfitt (2002), "The Lemba", pp. 43–44

- Vickers, Steve (8 March 2010). "Lost Jewish tribe 'found in Zimbabwe'". BBC News. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- Tudor Parfitt (2008). The Lost Ark of the Covenant. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0007262670.

- Time, "A Lead on the Ark of the Covenant," Biema, David Van, 02/21/2008

- ReporterNews, "Professor says he found Ark of the Covenant," Hamm, Britinni, 03/13/2008

- World Jewish Congress, Lemba tribe in southern Africa has Jewish roots, genetic tests reveal, 03, 18, 2010

- World Jewish Congress. "Lemba tribe in southern Africa has Jewish roots, genetic tests reveal". World Jewish Congress. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- "Zimbabwe displays 'Ark of Covenant replica'", BBC News, 18 February 2010 accessed 7 March 2010

- "ZDFE.factual - ZDF Enterprises".

- Parfitt, Tudor, The Lost Ark of the Covenant, Harper Collins Publishers

- Spurdle, AB; Jenkins, T (November 1996), "The origins of the Lemba "Black Jews" of southern Africa: evidence from p12F2 and other Y-chromosome markers.", American Journal of Human Genetics, 59 (5): 1126–33, PMC 1914832, PMID 8900243

- Thomas, MG; Parfitt, T; Weiss, DA; et al. (1 February 2000), "Y Chromosomes Traveling South: The Cohen Modal Haplotype and the Origins of the Lemba – the "Black Jews of Southern Africa"", American Journal of Human Genetics, 66 (2): 674–86, doi:10.1086/302749, PMC 1288118, PMID 10677325

- Parfitt (2002), "The Lemba", pp. 47–48

- Schindler, Sol. Review: "The genetics of Jewish ancestry", about Abraham's Children: Race , Identity and the DNA of the Chosen People by Jon Entine, The Washington Times, 28 October 2007

- Hamilton, Carolyn (2002). Reconfiguring the Archive. Springer. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-4020-0743-9.

- "The Lemba, The Black Jews of Southern Africa", NOVA, Public Broadcasting System (PBS), November 2000, accessed 26 February 2008

- Parfitt (2002), "The Lemba", p. 49

- F.L. Mendez et al., "Increased Resolution of Y Chromosome Haplogroup T Defines Relationships among Populations of the Near East, Europe, and Africa", BioOne Human Biology 83(1):39–53, (2011)

- Himla Soodyall; Jennifer G. R Kromberg (29 October 2015). "Human Genetics and Genomics and Sociocultural Beliefs and Practices in South Africa". In Kumar, Dhavendra; Chadwick, Ruth (eds.). Genomics and Society: Ethical, Legal, Cultural and Socioeconomic Implications. Academic Press/Elsevier. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-12-420195-8.

- Lost Tribes of Israel, Transcript, NOVA, Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), aired 22 February 2000

- Mohlomi, Setumo-Thebe. "Dilemma for the Lemba of Zimbabwe". The M&G Online. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

Further reading

- Junod, H. A. "The Lemba". Folklore. XIX (3): 1908.

External links

- "Lost Tribes of Israel (2000)" (PBS documentary on the Lemba and their origins), February 2000

- BBC News – Lost Jewish tribe 'found in Zimbabwe'

- "The Lemba, their origins and the Ark", Extrageographic

- Scholar's Ark of the Covenant Claims Spark African Storm