Nicholas Exton

Sir Nicholas Exton (died 1402) was a medieval English merchant. A leading member of the Fishmongers' Company and citizen of the City of London, he was twice elected Mayor of that city during the troubled years of the reign of King Richard II. Little is known of his personal background and youth, but he became known at some point as a vigorous defender of the rights of his Guild. This eventually landed him in some trouble for attacking the then-current Mayor, and he was fined and imprisoned as a result. The situation soon reverted to his favour with the election as Mayor of Nicholas Brembre, a close ally of his. During this period Brembre was a loyal supporter of the King, who at this time was engaged in a bitter conflict with some of his nobles (known collectively as the Lords Appellant). They managed to manoeuvre the King into surrendering some of his authority, and this, in turn, weakened Brembre, who was eventually executed by the Appellants for his support of the King.

Nicholas Exton | |

|---|---|

Arms of Exton, blazoned Azure a cross argent between twelve crosses crosslet fitchée or.[1] | |

| Lord Mayor of London | |

| In office 1386–1389 | |

| Personal details | |

| Died | 1402 |

|

By then, Exton had in turn been elected Mayor. Although for a while he and Brembre worked together in running London, when his predecessor fell from influence, Exton effectively deserted him, even to the point of being partially responsible for Brembre's eventual hanging. Exton's primary policy throughout his two periods as Mayor was probably based on a desire to maintain the city's neutrality between the feuding parties. On the other hand, he appears to have personally profited from the Appellants' period of rule, and it seems that there was some dissatisfaction with him in London, even if he was subsequently cleared of any wrongdoing by parliament. His later years are as obscure as his youth; known to have married at least twice, he seems to have had no children and died in 1402 at an unknown age.

Background and origins

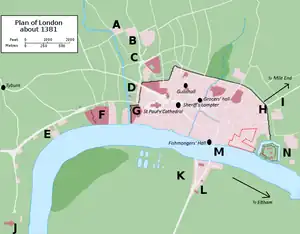

London

London in the late Middle Ages has been described as "the largest port, the largest market and retail outlet for luxuries and manufacture, and the largest employer in fifteenth-century England".[2]

Nationally and financially, it was the most important trading post in the country, only a few years later handling over 60 per cent of English trade abroad.[4] Throughout the later Middle Ages maintaining control of (and influence in) London was of fundamental importance for every monarch.[5][note 1] London meant close proximity and access to the hub of royal administration, justice, and patronage, as well as Parliament and the King's Council at Westminster.[6] The City, though, had also been hit heaviest by the King's poll taxes of 1376–81, providing even more "irritation and labour" for Londoners.[7]

Governance of London and relations with the crown

"...Divisions within the city itself, between citizens and the unenfranchised, the merchants and artisans, and the bitter economic rivalry between the different guilds, all destroyed the possibility of a united front" against the 1381 rebels.[8]

London was governed and administered by its successful merchant class, who were organised by their respective trades into different Guilds (or "misteries"). The mercantile guilds were sufficiently wealthy both in themselves and in their members to form a political upper class in the city.[9] They governed through the Common Council and in the person of the Aldermen, Sheriffs, and Mayor. The Council was "omnicompetent... [and] difficult matters which involved dealings with the king and royal government were frequently referred to it".[10] The city, however, was politically turbulent at this time.[note 2] Although at least one contemporary (Froissart) believed that Richard II favoured London at the expense of the rest of the kingdom, it is likely that he disliked the Londoners as much as they did him. But, they had to live with each other: the Crown depended on the wealth of London's merchants—the subsidies they paid and the loans they made—[12] and the City relied on the King to protect its trade abroad and liberties at home.[4] Throughout the 1380s, though, the politics of the City of London tracked those of Westminster, and if indeed England "was all but on the brink of civil war", then Londoners were also split between those who supported the King and those his opponents.[13] Yet these divisions within London's political society were not due to high politics. They were part of a deeper struggle between political factions over the fundamental governance of the City and the direction of its civic society.[14]

It was during this period of crisis that Nicholas Exton first appears in contemporary records. It is possible that the factional strife within London's government in the early 1380s,[15] which influenced City politics for half a generation[16] (including during Exton's mayoralty), may have had similar causes to those that encouraged some Londoners originally to join the Great Revolt.[15]

Political career

Nothing is known of Nicholas Exton's date of birth or youth, and little of his early years. He is known to have been involved in an Internecine dispute within the fishmongers' guild in 1364, when he was in a faction opposed especially to the wealthy and powerful Sir Robert Turk, a relative of Lord Burghersh.[17] Unfortunately, due to a dearth in internal records for the guild, historians know little as to day-to-day political activities.[note 3] He was elected Member of Parliament for Middlesex[18] to attend the June 1369 session at Westminster.[19]

London had been experiencing political tumult[20] ever since the 1376 Good Parliament (Exton attended),[21] which had caused radical constitutional change in the city, including annual aldermanic elections.[22] Caroline Barron has summed up this tense period:

It was not simply the intention that existing aldermen should be re-elected, rather there was to be a complete turnover of aldermen every year, although a man could be brought back to the aldermanic bench after a year's absence. The new system was fraught with difficulties and introduced an unwelcome instability in city government. [22]

King Edward III died in 1377, by which time Exton had become a leading citizen of the city.[23] To make matters worse, in 1381 the Peasants' Revolt erupted. This was a series of uprisings across the country, of an extent which had never been seen before. London, as the capital, was a focus of the rebels, who marched on it from Kent and Essex. But the rebels did not only come from outside of London; they were already within the city. Indeed, it is probable that Exton knew some of them personally.[16][note 4] It had been fellow-members of Exton's Guild of Fishmongers who had allowed the rebels outside the city gates entry to the City.[24]

Exton is known to have obtained royal pardons for some[25] of the Londoners involved in the revolt, some of whom had been condemned as its leaders in the city.[21] Most notably, this included Walter atte Keye, who had attempted—or at least threatened—to burn down the Guildhall.[26] On the other hand, the Mayor and many aldermen assisted King Richard in raising an armed force to confront the rebels with on 14 June 1381. The Mayor, William Walworth (who personally killed the over-all leader of the rebels, Wat Tyler) was a fishmonger like Exton,[note 5] and also accompanying them was Nicholas Brembre.[28] Both Walworth and Brembre, in fact, were knighted after the rebels had submitted;[29] but, although popular with the King, they and their guild were gradually losing their grip on power in the politics of London. Increasingly weakened by internal pressures, they were becoming only nominally in charge.[24] Following the crushing of the revolt, Exton began involving himself directly in the government of the city. On 12 March 1382 he was elected alderman for Billingsgate Ward,[30] an office he was to hold another seven times[31] until 1392.[32]

The leading men of this prestigious company enthusiastically exercised their right as citizens to deal wholesale in any goods, especially cloth, rather than dirtying their hands with fish.[33]

Justin Colson

By the early 1380s he had become an "active" spokesman for the Fishmongers' Guild, of which he was a member.[34] His guild had a monopoly on the wholesale fish market.[31][note 6] Controlling the sale of a staple food as it did made them immensely powerful in London politics.[37] Exton too was becoming of increasing importance thanks to the King's patronage, and acquired a swathe of rewarding offices, including collector of the port's wool customs and subsidies,[34] surveyor of the murage,[38] and Mayor of the Westminster Staple.[39] These positions were both financially lucrative and politically influential.[40] It is also likely that, as a citizen of the city of London, with the legal right to trade in goods beyond the remit of one's guild, he would have taken full advantage of such a right.[33]

Relations with Geoffrey Chaucer

Exton's appointment as a port subsidy- or tax-collector was not an unusual one: "many of the greatest, and in some cases, the most infamous" London merchants were appointed to the position at this time.[41][note 7] The poet Geoffrey Chaucer had been appointed controller of the customs in 1374, so it is almost certain that he oversaw Exton's tenure as a tax-collector;[42] certainly Brembre was Chaucer's colleague in the wool custom.[43][note 8] They were also both supporters of the King—or at least were "both cultivated" by him, probably in order to create a "royalist" party within the City's administration. King Richard supported Brembre's and later Exton's mayoralties,[46] and had already appointed Chaucer to be an esquire of the royal chamber.[47] Indeed, it has been suggested that Chaucer modelled his merchant (from The Merchant's Tale) on one such as Exton—a "real man who was well known to Chaucer's audience".[48] Chaucer already seems to have been predisposed to Exton's faction in the Common Council, and they were thrown together again in 1386, as a result of the Wonderful Parliament. Here, a petition was presented by the Commons, to remove all customs controllers who had been granted life-terms in the office (i.e., such as Chaucer).[49]

Opposition to Northampton's reforms

Following the rebellion, the reputations of Wentworth and the incumbent common council had been tarnished, and this allowed the election of a radical,[50] John Northampton. Northampton was Mayor between 1381 and 1382 and had very much a populist agenda.[31] He was particularly vocal in his desire to break the monopoly of the Fishmongers. This was also a popular policy, as it would bring down the price of fish for the citizens of London[51] and open London's markets up to the less-prosperous.[31] Exton, on the other hand, wanted to preserve the City's existing price controls.[52] He and his fellow fishmongers took the view that other victuals (bread, wine and beer, for example) were also monopolies, and so failed to see why their particular practices—restrictive or not—should be removed from solely themselves.[53] Exton's party has been called the "capitalist party" of London politics of the time.[21] The smaller misteries on the other hand, for instance, those of craftsmanship and manufacturing, stood for free trade.[54] The victualling guilds' desire to maintain their monopoly made them antagonistic towards foreign traders,[54] to the extent that the fishmongers were in the habit of seizing fresh fish from alien fishermen, selling at a heightened price, and only repaying when and what they liked.[55] Northampton's mayoralty was beset by violence, with riots and running street battles being commonplace, as members and apprentices of the clothing and manufacturing guilds clashed with those of the victuallers on a regular basis.[56][57] But Northampton was eventually able to introduce free trade in London fish in the parliament of 1382. Exton appealed to the King on behalf of his guild: Northampton immediately denounced the fishmongers for being the only thing in London that was stopping the city from existing in "unnitee amour and concorde".[58] Exton claimed that Northampton and his party were prejudiced against them, as did Walter Sybyll; in turn the fishmongers generally and Sybill[note 9] specifically was then accused of taking part in the Peasants Revolt in London in 1381 and of assisting the rebels.[57]w

Northampton's mayoralty has been described as a disaster for the fishmongers: the new Mayor deprived them of their retailing rights, and revoked their eligibility to hold civic office in the city.[59] Exton and Northampton were by now bitterest enemies.[21] Naturally, Exton joined Northampton's political opponents, chief of whom was Nicholas Brembre, who had earlier accompanied William Walworth against the rebels. Exton's advocacy for the Guild appears to have led him to make robust and vigorous comments regarding his opponents, to the extent that it was noted in the 1382 Letter-Book that Exton had made "opprobrious words used to the aforesaid Mayor [Northampton]". For this, it seems that Exton was removed from his aldermanry less than a week later. He may, however, have actually requested his own removal,[18] as he had already previously offered a "grosse somme" of money towards doing so.[60][note 10] This was not his whole punishment though. He was also deprived of his city citizenship,[62] sentenced to a year's imprisonment[63] (although this was immediately cancelled),[64] heavily fined,[63] and forced to leave the city. This last was also only of a short duration.[65] All of these punishments may have been at the direct order of Northampton himself.[66] In all, he both lost his office of Alderman and had to leave the City for a period, even if he had also escaped lengthy imprisonment[67]- all for having spoken-ill of the Mayor and aldermen in parliament.[68] The same year, 1382, he appointed one John Wroth as his mainpernor, and his need for a bondsman was probably a reflection on his troubled circumstances during this time.[69]

Only a month later, though, in September 1382, Exton was back, and reiterating the same points in parliament.[18] The fishmongers (and by extension the other victualling guilds), argued Exton, were entitled to the same rights of exclusivity as other companies: "If the retail in fish was to be thrown open to foreigners for the common Dukinfield", paraphrases one commentator on Exton's remarks, "then so should all the others". This line of argument provided Northampton's supporters with the opportunity to accuse Exton of defying the traditional liberties of the city. This, they claimed (as that year's Letter Book tells us) was "a manifest injury to all citizens" of London.[63]

Exton's fellow guildsmen, of course, took rather a different view. They acclaimed him for his spirited stand against Northampton. Later, one of them stated in court that "he and all the other fishmongers of London were bound to put their hands under the feet of Nicholas Extone for his deeds and words on behalf of the mistery".[18] It was, too, recorded in the City's Letter Book that Exton performed "good deeds and words" on behalf of his Guild.[70]

"It was only in that year, when he succeeded Brembre as Mayor and proceeded to a double term of office, that he became a figure of national importance. It fell to Exton, in fact, to guide London through the perils of the Appellant revolution".[21]

Mayoralty of Nicholas Brembre

John Northampton served two terms in office. In 1383, he lost the mayoral election to Nicholas Brembre, who would be Mayor for the next three years.[71] He almost certainly one this election by the simple method of filling the Guildhall's main hall (where the election took place) with his own (armed) supporters,[31] as well as also concealing them around the building.[72] General lawlessness had continued in the city, and it has been suggested that Richard II assisted the election of Brembre in order to suppress dissent. Almost immediately a cordwainer was summarily executed as an example, with the King's backing.[73] Within a few months Northampton was on trial for sedition (between February and August 1384), with Exton attending, again in support of Brembre.[18] Brembre—a member of the Grocers' Company—was sympathetic to the Fishmongers.[64] Early in Brembre's mayoralty, Exton petitioned the Common Council against his condemnation in 1382. His appeal was, unsurprisingly, successful, and all records of Exton's previous conviction were struck through in the Council's Letter Book.[64] In 1384, for example, he (together with William Maple) paid the future Archbishop of Canterbury, Roger Walden, 80 marks in order to settle a dispute over a Southampton Cog between the two.[74]

Exton was soon elected Sheriff of London, and in 1385 was returned again as alderman for Billingsgate.[18] The parliament opened in October 1385, to which Exton was elected in pleno parliamento, was politically tense, as the Commons laid articles of impeachment against Richard II's favourite, the Chancellor, Michael de la Pole.[75] Exton was part of a delegation of merchants who met the King to request John Northampton's execution.[66] The King meanwhile had requested a subsidy or war tax; as a result, two joint-supervisors of taxation from the Lords Temporal and Lords Spiritual were appointed, to authorise all payments requested by the council. In January the following year, Exton was appointed a collector of the tax, with instructions to "take, receive and keep" the subsidy, to ensure it was spent solely on military activities and then to certify the same to the Lower House.[76] By Easter, he and his fellow collector had collected some £29,000 in tax.[77] For this work, he was paid £20 in wages, as well as a further £46 for his expenses. Further, he was also able to avail himself of free boat usage on the River Thames.[78] In October 1386, Brembre came to the end of his three terms of office, and Exton was elected in his stead.[79] Just before Exton was elected (by possibly a matter of a few days), Brembre had visited the King at Eynsham Abbey, where he may have encouraged Richard to expect and rely on London's support in the King's on-going struggle against the Lords Appellant.[80]

Twice Mayor of London

The years 1387 to 1390 have been described as critical in London history,[16] and the Mayor was the single most important figure in the City's government. Yet Exton's election as Mayor would still have been an occasion of some of the most magnificent pageantry the city experienced, described thus:

First of all, there were the chevauchés-the Ridings-of the newly-elected Mayors. In these great processions... the Companies turned out, court members, prentices, and servingmen, the first on horseback, the rest on foot, in their colours and with their banners; they were preceded by minstrels, and the streets were hung with tapestry...Next there were the usual Companies' festivities, and then the extraordinary ceremonies.

The war with France was going badly, there was a financial crisis (blamed to some extent on the King's profligate misuse of patronage)[82] and the King was growing in unpopularity. So badly was the war going in fact, that just as Exton started his first year as Mayor, there was a serious threat of French invasion. By September 1386 a French fleet was reckoned in England to be on the verge of sailing,[83] and a 10,000-strong army surrounded the City of London to protect it from the expected invasion.[84]

First term, 1386–7

Exton was elected Mayor of London on 13 October 1386.[85] Within the first few weeks of his term, he made a loan to the crown of the massive sum of £4,000—on behalf of the city—which was to be repaid early the following year. Exton's election also had the side-effect of further ensuring the fishmonger's control over the wool subsidy collection.[86] Exton had to lead the city through a particularly turbulent time in English politics. At the "Wonderful Parliament" in November that year the King's political opponents—the Lords Appellants— attempted to restrict King Richard's authority, and make him accountable to a council of nobles.[87] During that parliament, the St Albans chronicler, Thomas Walsingham, reports that on one occasion, the King planned[74] on having some of them arrested[88] or even ambushed and killed. Exton, the chronicler says, had discovered the plan and pre-warned the Commons,[74] sending a messenger to Westminster.[89] Knighton goes so far as to say that the plot was put off solely due to Exton refusing to be party to it.[90] Either way, contemporary sources partisan to the Appellants report that Exton's uncooperativeness was responsible for the failure of "palace intrigues".[91] The supposed plot against the Appellants must have occurred within weeks[92] of Exton's election as Mayor in October 1387.[93]

As a recent biographer has commented, Exton and Brembre continued their close co-operation.[18] In particular, Exton carried on prosecuting and imprisoning their mutual enemies.[42] With Exton now running London's government, Bembre was free to devote himself to national politics.[94] Perhaps inevitably, he acted as the City's representative at Westminster.[95] Also inevitably, the campaign to destroy John Northampton and his legacy continued. In March 1387, Exton had Northampton and his associates imprisoned. By April, when it looked like the king was on the verge of pardoning Northampton, Exton was at the forefront of opposition to clemency.[66] That same year, under Exton's supervision, the common council authorised the burning of the reform legislation of John Northampton.[18] Exton had this done publicly, outside the Guildhall itself.[96] This was a single volume known as the Jubilee Book;[97] depending on the political hue of the administration of the day, it either "comprised all the good articles appertaining to the good government of the City" or "ordinances repugnant to the ancient customs of the City".[98] The book's destruction made Exton complicit, in some eyes, with the excesses of Brembre's mayoralty, and has been described as characterizing the "brutal and spectacular intolerance" Exton and Brembre shared.[97][note 11] The rebels of 1381, under Walter atte Keye, had already attempted to seize and destroy the Jubilee Book as part of their campaign against writs, charters, and the other instruments of City government, but had failed in their assault of the sheriff's compters. Where the mob failed, however, Exton succeeded.[note 12] He seems to have generally avoided public debate or oversight whenever possible (for example, according to a contemporary, the Jubilee Book, for example, was burned, "wyth-out counseille of trewe men"), focussing on shoring up the power of his and his allies' guilds.[97] This included continuing attacks on foreigners in the City. In July 1387, for the declared purpose of avoiding "shame and scandal to the City of London," it was forbidden for any foreigner to become an apprentice within a guild.[102][103] Atte Keye, incidentally, had received a pardon from the King—at Exton's behest—only one month before the burning of the Jubilee Book.[98]

In September 1387, the King wrote to Exton and expressed his satisfaction, having learned from Brembre that, in the King's own words, "good and honourable men"[104] (Hugh Fastolf and William Venour)[105] had recently been elected Sheriffs of London. So widely were these viewed as partisan and avowedly political appointments—Fastolf's particularly—that it drew particular comment in the Cutlers' Guild's later petition against Exton.[104]

Second term, 1387–8

It was said that they learned that those who had gone to treat with the King would have been fallen upon by armed men and slain... but that Nicholas Exton, the Mayor of London, having refused to countenance the evil, a deep and wicked plot was spread about and the scandal gradually uncovered.[106]

In October 1387, Exton was re-elected Mayor. This was again enabled by the King—rege annuente—who threatened to forbid his Barons of the Exchequer from taking the official oath of any candidate the King deemed not to be likely to "govern the city well".[107] The King had left Westminster in January 1387[74] and spent much of the year travelling throughout the Midlands.[74] He returned to London in November,[108] The King was by now seeking revenge,[109] and with (he thought) the legal backing to achieve it.[110][note 13] Exton went beyond the city gates to meet the King with the Mayor and aldermen dressed in the royal colours of red and white.[111][note 14] The King's reception may have been more formal than enthusiastic.[57] But it was important for the King to gain the backing of the City of London, and Exton would seem to have attempted to achieve this for him by requesting that all the craft guilds swear an oath to "live and die" with Richard.[113] This oath also contained a further denunciation by the Common Council of John Northampton. This clearly linked Exton's tentative support for the Crown with that of monopoly for his guild.[112] But although Exton was able to bring Richard the Londoners' oath to stand by the King, the Mayor was unable to further aid the Richard materially, when the King urgently wished to raise an army.[114] Knighton's Chronical suggests that the King himself then attempted to force the City to raise that force.[113] He probably sought the direct assistance of Exton to do so.[115] On 28 November, Exton had to present himself at Windsor, and the King demanded to know how many soldiers the City could provide.[116] To this, Exton informed him that the inhabitants "were in the main craftsmen and merchants, with no great military experience" and that the only reason they could ever be placed under arms was to defend the city itself.[117] Nevertheless, the King despatched a warrant for the arrest of the rebel Lords, and it was the responsibility of Exton to execute it in London. However, says Jonathan Sumption, Exton "quailed before such a task [and] resolved that the city had no business executing a warrant of this kind".[118] On 20 December the Lords Appellant inflicted a crushing defeat on the Court party at the Battle of Radcot Bridge in Oxfordshire. The consequent and abrupt shift of political power towards the rebels changed the position dramatically.[112][note 15] Naturally, Exton authorised the opening of the city gates to the Lords—although only "once their victory [over the King] had become certain".[18] Exton may have personally greeted the Lords outside the city gates (much as he had done with the King) and accompanied them into London.[120] Even so, later attempts by the Appellants to get Exton and the Londoners to actively support and commit to their anti-Ricardian faction still failed.[121]

According to the St Alban's Chronicle, Exton officially distributed food and drink to the Lords' encamped retainers in an attempt at dissuading them from treating the City as the spoils of victory.[122] This was a particular worry for the rich, whose great houses would be first targeted.[123] Favent reports that the Duke of Gloucester, a leading Appellant, on hearing Exton's pledges of the city's loyalty, remarked, "Now I know in truth that liars tell nothing but lies, nor can anyone prevent them from being told".[120] This remark may have been a reflection upon the extent to which Exton by now had a reputation among his peers for double-dealing.[124] The King also expressed displeasure at Exton's obeisance towards the Appellants, and deliberately pardoned Exton and Brembre's old rival, John Northampton, who until then was still in disgrace, in retaliation[125] Exton himself had personally annulled Northampton's London citizenship earlier in the year.[126]

"...At the beginning of the parliament certain mercers, goldsmiths, drapers, and other restless elements in the city of London presented in the parliament bills of complaint against the fishmongers and the vintners, whom they described as victuallers, unfitted in their judgement to control a city so illustrious... they petitioned that their mayor, Nicholas Exton, be deposed".[127]

– The Westminster Chronicle

The Appellants proceeded to prosecute those they considered the King's political allies. This included Nicholas Brembre,[128] and at the Merciless Parliament of 1388, he was condemned to death.[129] Exton seems to have acquiesced in the proceedings against (and subsequent hanging of) his earlier ally.[18] Exton had also been a leading member in Brembre's London "Ricardian faction" and stayed with Brembre as long as he could. He deserted him decisively sometime after March 1387.[130] Exton was in, it has been said, a "particularly difficult position".[67] He and other aldermen were questioned before an assembly of Appelant lords in parliament; they were the same group of men who, under Brembre, had petitioned John of Gaunt against the duke's support of a pardon for John Northampton.[131] Questioned as to whether Brembre could be supposed to have realised that his actions were treasonous, Exton is supposed to have replied that he "supposed he [Brembre] was aware rather than ignorant of them"[92]—or, as May McKisack put, was "more likely to be guilty than not". Either way, it was this judgement that persuaded the Appellant Lords to condemn Brembre.[132] Brembre's fate, then, had been sealed by Exton and "those that knew him best",[133] however reluctantly they might have opined.[112]

Exton seems to have tried to continue Brembre's tradition of loyalty to the crown, but, significantly, "within limits never acknowledged by the headstrong Brembre".[93] His support for Richard was almost certainly more passive than his predecessor's: As J. A. Tuck said, London "was probably divided, with Brembre trying to win it over to the King's side and Exton... trying to keep it out of politics".[134] At the same time, Exton profited financially from the crisis. One of the responsibilities that the King's new officers (imposed on him after the Wonderful Parliament) had was to dispose of the forfeited estates of those condemned by the Appellants. This responsibility they embarked on with zeal, and "at what were, we may suspect, attractive prices". Exton, says Professor Charles Ross, was one of their biggest purchasers. He paid 500 marks for some de la Pole estates,[135] (for example, the manor of Dedham, Essex in 1389)[136] and 700 marks for a manor of Sir John Holt's.[135] In May 1388 Exton loaned the Appellant-controlled government the large sum of £1,000. To put this figure into context, for their part, the whole city lent £5,000.[137]

Attacked by fellow merchants

|

The Westminster Chronicle reports that when Exton's term was up in October 1388, Richard II was willing for Exton to continue as Mayor into 1389 (even if he had supposedly thwarted royal plans to assassinate members of parliament).[139] But Exton's personal, if private, support for Richard, such as it was, may have earned him the distrust of Londoners.[21] Just before Exton's mayoralty ended, the parliament then being held at Cambridge by the victorious Lords Appellant formally pardoned Exter—[18] at his own petition[140]—for any treasons or felonies he may have committed in previous years. This parliament also forbade Londoners from criticising him regarding alleged derogation of the city's liberties.[18] This referred to a rumour currently in circulation that in the previous (February 1388) parliament, Exton "sought to jeopardise the liberties of the city by petitioning parliament to make Robert Knolles captain of the city."[141] The Cutlers' Company even petitioned that Exton and other members of his administration should be sacked and then prosecuted for being collaborators of Brembre.[142] Exton had, the Cutlers suggested, been personally selected by Brembre to replace him and continue Brembre's "fauxete and extorcions" on the City.[104] This, said Walsingham, meant that the governance of London continued to be held "par conquest et maistrie",[143] which was fundamentally against the City's tradition of free and open elections of its Mayors.[111] The Cordwainers' Guild also presented a similar petition,[144] and there were many others presented by London craft guilds. Thirteen of these survive to the present day.[111][note 16] That of the Mercers claimed that Brembre was originally elected due to his "stronge hand", and that Exton continued in his path, corrupting elections, and using brute force to do so.[146] Others called more broadly for the revival of the John Northampton's 1382 statute which forbade victuallers (and therefore fishmongers) from holding office in the city (including, of course, that of the mayor).[111] Exton had, after all, points out Ruth Bird, been rather notorious ever since he had so vociferously defended his guild's rights at the beginning of the decade.[67]

The Lords replied that Exton and the others "have been questioned about this matter [and the Lords] have concluded that Exton made no attempt to do this by petition or otherwise".[74] It is possible that on-going and pressing political issues distracted the Lords from pressing the case against Exton.[104] After all, "Exton's 'royalist' credentials seemed hardly less pronounced than Brembre's own, whom of course they had removed brutally".[147] The Lords took a "ruthlessly pragmatic" approach towards Exton, probably due to the fact that he was still—just— in office. Their lack of action against him may also have been the result of a deal which saw them protect Exton in return for his abandonment of Brembre.[148] For his part, the rumour that he "sought the derogation and annulment" of London's liberties was probably sufficiently grave for Exton to seek the protection of the Appellant Lords. Indeed, he probably had good reason to fear that his previous good relations with the King could yet be enough to turn the rebels against him.[149]

Later career

Exton continued to receive royal favour.[18] For instance, he received the wardship of a number of manors in Kent[137][150] and in 1387 the Constableship of Northampton Castle, replacing William Mores, a trusted servant of the King.[151] This he was able to subsequently exchange for a royal pension of 6d. per annum, "with the consent of the council".[137] Exton also received the settlement of debts owed him by Brembre, and unpaid since the latter's execution. This amounted to the relatively large sum of £450—by far the majority of Brembre's debts to other merchants were generally no more than a little over £100 and often in single figures.[152] He also received a Spanish sword from the King and was granted permission to buy many of Brembre's personal goods and chattels. In 1392, however, he once again, with other leading London citizens, incurred the King's anger during Richard's "quarrel with the city",[18] and was temporarily disgraced.[21] Throughout this period he was still holding the office he had with Brembre, remaining a collector of the customs.[137]

Richard II advised the City in 1388 to choose the next mayor as someone "trusty and loyal"—by which, of course, the King meant, loyal to him. However, the actual election of Nicholas Twyford was probably displeasing to him:[153] Twyford had previously been defeated by Brembre in 1384;[154] although never a supporter of John Northampton, he had regularly been opposed to Exton.[155] The "Merciless Parliament" held that year also, finally, stripped London of its right to monopolize the retail sale of goods.[154]

In 1390, he finally lost his position as collector of the wool subsidy, which he had held since 1386, firstly alongside Brembre, and after his execution, William Venour.[156]

Although his guild had regained their official civic rights in 1383, they did not see the restoration of their reading rights until long after Exton left office, in 1399.[59]

There were to be no further loans from the city to the crown after Exton's mayoralty until September 1397.[86][note 17]

He would later, in 1390, pledge £200 on Maple's behalf for the latter to keep the peace with a fellow merchant.[158]

In 1392 the King would commence a series of sustained attacks on the liberties of the city.[159]

Death and overview

Although Exton was "clearly a partisan figure"[18] in the politics of London, his most recent biographer has noted that he "nevertheless belonged to a ruling oligarchy whose shared interests often made it a force for stability"[18] in those politics. In any case, he managed to negotiate a difficult political period with little harm coming to him or the city under his mayoralty, even though this involved allying with both the crown and its opponents against the other on varying occasions.[18] Paul Strohm has suggested that, although Exton is often viewed as being politically sympathetic towards Brembre's views, Strohm says the difference between them is that Exton was "an honest and above-board player who did not scruple to expose his predecessor's hyperpartisan chicanery" and whose policies were much the same but lacking the "criminal excesses" of Brembre's.[160] Sumption, meanwhile, has summed up the Mayor as an "astute trimmer whose main objective was to stay out of trouble",[161] whereas an earlier biographer believed that Exton remained loyal to the King, but was unable to go against the general feeling of his compatriots.[123] Another recent historian takes a much darker view: that Exton was "a dangerous and powerful man who needed to be reminded of the consequences of placing private interests above those of the commonalty" and "every bit as fickle and unscrupulous" as Thomas Usk, whom the Appellants had themselves had executed.[162]

"Though Exton and his fellow aldermen acted in a craven manner, they may have saved the City from repression by the appellant lords, for the divisions since Northampton could have given a good excuse for interference; Exton had been close enough to the government of Richard II for the lords appellant to have taken action against him if he had not capitulated".[163]

– A. R. Myers

Either way, Exton's policy was clearly one of non-alignment,[164] if probably an "opportunistic neutrality".[112] The basis of Exton's problem was that the King had attempted—with some success—to build up a Ricardian faction in London politics in the early-to-mid 1380s (for example, Brembre). Whereas, actually, much of the City (including of course many who were close to Brembre) were often sympathetic to the Lords Appellant. Exton, it has been said, was at that "cross-current of considerable significance in the history of London".[16] He was also, more broadly, illustrative of the social mobility that political turmoil could induce: In 1382 he was effectively a pariah, only just avoiding imprisonment, yet four years later holding the highest office in the City.[64] Exton's career also illustrates the important part that royal intervention could play in the governance of London. The King had already supported Brembre and then Exton's candidatures; this was followed by a warning to London to elect a Mayor favourable to him and culminated in Richard seizing the City's liberties in 1392. Five years later, a Mayor died in office; rather than allow an election, he simply imposed his own candidate—one Richard Whittington.[113]

Exton was also the name of the murderer of Richard II in Shakespeare's play of the same name, although Shakespeare changed his character's first name to Piers.[165] The playwright took his information from previous chroniclers—for instance Raphael Holinshed and Edward Hall—who in turn may have taken their information from the first chronicle to name the killer thus.[166] This was Jean Creton, who between 1401 and 1402 wrote an account of the deposition and murder ("the only true account")[167] as he understood it to have occurred, at the commission of the Earl of Salisbury.[168][note 18] However, the only Extons known to be extant at this time are Nicholas, MP, Mayor, and fishmonger, and his probable relatives, none of whom is supposed within scholarship to have been the regicide.[169] It has been speculated at most that among his relatives, it is not impossible that he had another named Piers,[170] although there was no knight called such at the time.[171] Nigel Saul has suggested that "Exton" was actually a corruption of "Bukton", as Sir Peter Buckton was Constable of Knaresborough Castle, not far from Pontefract, where the King had died.[172]

Subsequent events

National politics remained as polarised and volatile in the years following Exton's mayoralties as during it, and, so connected as they were, did the civic politics of London.

Family

Nicholas Exton is known to have died in 1402; as much (or as little) is known regarding the last few years of his life as his youth. Something similar can be said regarding his private life. He is known to have married twice, to a Katherine, around 1382, and later to a Johanna[173] (also called Joan). In 1389 Exton and Joan received the manor of Hill Hall in Theydon Mount, conveyed to them by feoffees of Richard de Northampton. In 1390 Nicholas and Joan received a licence to found a chantry in the local church, providing an endowment of a half-acre of land and ten marks rent.(http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/essex/vol4/pp276-281#highlight-first)

As to whether he had any children, the issue is unclear. Paul Strohm suggests not, on the grounds that none are recorded.[18] Carol Rawcliffe, on the other hand, says he had a daughter Agnes, who became the ward of John Wade.[173] He made a will in 1399, in which he left properties to his brother and a remainder to the rector for masses and prayers.[18] It is possible that he was related to a contemporary M.P., Thomas Exton, who was a Common Councillor for Aldersgate Ward from June 1384 to March 1386, and was also prominent in his guild (he was a prominent Goldsmith, for which Company he was a property custodian).[174] Exton may also have been related to one Peter Exton, who was also a business associate of John Ward. Nicholas Exton named Ward as one of his executors; Exton and Wade had been business associates since at least the Hilary term of 1369 when Wade first acted as a feoffee for him. This was a role which he would continue to play until Exton's death, and he has been described as Exton's "close friend and business colleague". Exton had been a wealthy man, and the inheritance that Ward held in trust for Agnes must have been a sizeable one.[173] Thomas Exton, meanwhile, acted as a mainpernor for Wade to do so.[174] Agnes may later have married the son of Richard Pavy; she received a grant of £20 from Pavy's Isle of Wight manors in 1404.[175]

Notes

- "London was, moreover, the capital of England in part because of its proximity to Westminster. So kings processed through the city before their coronations and... London crowds provided the required "collaudatio" for usurpers such as Henry IV in 1399 and Edward IV in 1461".[5]

- Particularly following the Good Parliament of 1376. Barron points out that actually "for most of its history London had been turbulent".[11]

- Today, the earliest known muniment extant from the guild's early history is from 1590. Although much existed before that, almost everything was lost in the Great Fire of London in 1666.

- After Exton died in 1402, his children's guardian was John Cockaigne, Chief Baron of the Exchequer. One of those who stood surety for Cockaigne was one Richard Forster of the Saddlers' Guild- an ex-outlaw and 1381 rebel.

- Indeed, testament to the power of that guild, and their support from the King, the fishmongers provided seven Mayors of London in the late fourteenth-century.[27]

- The Church forbade the consumption of meat on many days of the year for the purpose of fasting.[35] Thus, alongside the meat trade, the Fishmonger's guild was the most important industry in London at the time. Their joint-market house had space sufficient to hold seventy-one market stalls and twenty lesser areas for their trades. In comparison, "most other traders were limited to a single street".[36]

- For instance, Sir John Philipot (d. 1384), who was elected to parliament at the same time as Exton, and also worked as a subsidy collector under Chaucer.

- Both Brembre and Exton were two out of seven collectors who were also Mayors, out of fifteen appointed by Richard II, further, both were mayors of the Westminster Staple, Members of Parliament, and aldermen of the city.[44] Says Coleman, "It seems not too fanciful to suppose that appointment to the wool customs was a quid pro quo about which the crown had little choice for as long as it made a habit of borrowing from London and Londoners".[45]

- For Sybil, see Bird, esp. p.57 n, for his "Billingsgate tongue"

- This is not necessarily unusual; the office was relatively strenuous and expensive.[60] Indeed, it was less than twenty years later that one John Gedney was even imprisoned for refusing to take up the office when elected.[61]

- A curious disparity in the dating of this event was identified by Ruth Bird, in that according to the City's own Letterbook, the book-burning may not actually have taken place until the year after Exton was petitioned against- when it was one of the most notable events of his mayoralty to be used against him.[99]

- The rebels demanded, for example, the immediate beheading "of anyone who could write a writ or official letter".[100] The Jubilee Book (so-called due to is compilation during Edward III's jubilee year, 1376-7), substantially and radically revised the city's ordinances, although due to its destruction by Exton, the book's precise contents remain necessarily vague. Nicholas Brembre had already had the book re-examined in 1384 with the intention of "preserving good ordinances and rejecting the bad", as was said at the time. It is due to Brembre's interest in the book that Exton's burning of it is seen to link their two mayoralties so closely.[101]

- During his time in the country, Richard intended to gather and consolidate his supporters.[43] In August 1387, in Shrewsbury, the King summoned the royal justices. Presenting a number of "Questions for the judges", as they have been called, to them, Richard wanted to establish once and for all the parameters and extents of the liberties and prerogatives of the Crown.[109] More, he wanted an explicit condemnation of those he held responsible as traitors, and a ruling that, therefore, they should die as traitors.[110] Most importantly, he intended to establish whether the law passed imposing his unwanted council was "derogatory... to the lord King". The King clearly intended, despite the constraints parliament had set on his authority, to regain his previous political pre-eminence.[109] The judges, at least, gave him the answers he required.[43]

- "In una secta, alba silicet et rubea," says the Westminster Chronicle.[112]

- Notwithstanding Exton's claim that Londoners would not fight, the antiquarian John Noorthouck noted in the eighteenth century that Gloucester's army at Radcot Bridge was composed "chiefly of Londoners".[119]

- Others came from the Bladesmiths', Bowyers', Fletchers' and Spurriers' Guilds ("all of them crafts furnishing implements of war"), as well as the Cutlers.[144] Also see, for example, SC 8/21/1006 (from the Mercers) and SC 8/21/1001B (from the Leathersellers). One of the few Guilds not to petition against Exton, in fact, was the Horners.[145]

- Loans to the crown in this period have been described as a political "quagmire" for the city by one historian of the period.[157]

- Jean Creton was Philip the Bold's varlet du chambre, on a diplomatic mission to the English court, and was with King Richard at the time of his expedition to Ireland and deposition. Indeed, his account of the first has been called the best of the many that were composed at the time, although he had left England by the time Richard was killed.[168]

References

- Burke, Bernard (1884). The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales. London: Harrison & Sons. p. 335.

- Hicks 2002, p. 50.

- Lobel 1990.

- Bolton 1986, p. 12.

- Barron 2000, p. 410.

- Barron 2000, p. 21.

- Barron 1981, p. 19.

- Barron 1981, p. 7.

- Postan 1972, p. 243.

- Barron 1970.

- Barron 1971, p. 133.

- Barron 1971, pp. 129–131.

- Hatfield 2015.

- Barron 1981, p. 99.

- Prescott 1981, p. 133.

- Steel 1974, p. 35.

- Rawcliffe 1993b.

- Strohm 2004a.

- Given-Wilson et al. 2005a.

- Bolton 1981, pp. 123–124.

- Steel 1974, p. 36.

- Barron 2005, p. 137.

- Steel 1974, pp. 33–34.

- Hilton & Fagan 1950, p. 41.

- Bird 1949, p. 60.

- Sharpe 1907, p. lii.

- Billington 1990, p. 98.

- Barron 1981, p. 5.

- Barron 1981, p. 8.

- Beaven 2018, pp. 22–32.

- Strohm 2004b.

- Beaven 2018, pp. 379–404.

- Colson 2014, p. 28.

- Oliver 2010, p. 76.

- Colson 2014, p. 23.

- Billington 1990, p. 97.

- Hope 1989, p. 23.

- Kuhl 1914, p. 271 n. 8..

- Rich 1933, pp. 192–193.

- Oliver 2010, p. 76 n. 51.

- Goddard 2014, p. 177.

- Robertson 1968, p. 161.

- Sanderlin 1988, pp. 171–184.

- Coleman 1969, p. 182 + n.2,3,5.

- Coleman 1969, p. 185.

- Barron 1971, p. 147.

- Gray 2004.

- Brown 1979, p. 252.

- McCall & Rudisill 1959, pp. 276–288.

- Barron 1981, p. 9.

- Barron 1971, p. 141.

- Barron 2000, p. 142.

- Barron 1971, pp. 141–142.

- Hilton & Fagan 1950, p. 40.

- Robertson 1968, p. 138.

- Oman 1906, p. 156.

- Robertson 1968, p. 151.

- Bird 1949, p. 57.

- Colson 2014, p. 22.

- Ellis 2012, p. 14 n. 4.

- Barron 2005, pp. 138–139.

- Hanrahan 2003, pp. 259–276.

- Nightingale 1989, p. 27.

- Ellis 2012, p. 15.

- Bird 1949, p. 95.

- Dodd 2011, p. 405.

- Bird 1949, p. 94.

- Myers 2009, p. xiv.

- Rawcliffe 1993d.

- Ellis 2012, p. 14 n. 2.

- Barron 2005, p. 334.

- Bird 1949, p. 69.

- Barron 1971, pp. 146–147.

- Given-Wilson et al. 2005b.

- Roskell 1984, p. 75.

- Sherborne 1994, p. 101.

- Sherborne 1994, p. 102.

- Sherborne 1994, p. 115.

- Riley 1861, p. 646.

- Goodman 1971, p. 22.

- Besant 1881, p. 165.

- Tuck 2004.

- Roskell 1984, p. 43.

- Sherborne 1994, pp. 113–114.

- Bird 1949, p. 145.

- Coleman 1969, p. 187.

- Goodman 1971, pp. 13–15.

- Saul 1997, pp. 157–161.

- Mortimer 2008, p. 66.

- Duls 1975, p. 36.

- Goodman 1971, p. 18.

- Strohm 2015, p. 152.

- Strohm 2015, p. 150.

- Bird 1949, p. 90.

- Strohm 2006, p. 15.

- Myers 2009, p. xvi.

- Turner 2007, pp. 21, 29–30, 11.

- Barker 2014, p. 276.

- Firth Green 2002, p. 393 n. 1.

- Barron 1981, p. 4.

- Barron 1981, p. 16.

- Réville 1898, p. cxxviii + n.

- Dobson 1983, p. 345.

- Strohm 2006, p. 21.

- Barron 2005, p. 335.

- Strohm 2015, p. 175.

- Barron 1971, p. 148.

- Roskell 1984, p. 50.

- Saul 1997, pp. 171–175.

- Davies 1971, pp. 547–558.

- Dodd 2011, p. 413.

- Strohm 2006, p. 28.

- Barron 1971, pp. 148–149.

- Bruce 1998, p. 74.

- Barron 2000, p. 11.

- Goodman 1971, p. 28.

- Barron 2005, pp. 17–18.

- Sumption 2012, p. 635.

- Noorthouck 1773, p. 81.

- Oliver 2010, p. 153.

- Robertson 1968, p. 165.

- Given-Wilson 2016, p. 50.

- Bird 1949, p. 92.

- Dodd 2011, p. 412 n. 78.

- Turner 2007, p. 32 n. 5.

- Robertson 1968, p. 157.

- Turner 2007, p. 27.

- Favent 2002, pp. 231–252.

- Barron 1999, p. 148.

- Strohm 2015, p. 177.

- Bird 1949, p. 98.

- McKisack 1991, p. 457.

- Oliver 2010, p. 104.

- Tuck 1973, p. 111.

- Ross 1956, p. 571 n. 1.

- Victoria County History 2001, p. 165.

- Bird 1949, p. 97.

- Ellis 2012, pp. 416–417.

- Duls 1975, p. 60.

- Bird 1949, p. 96.

- Given-Wilson et al. 2005c.

- Rawcliffe 1993a.

- Round 1886, p. 256.

- Welch 1916, p. 49.

- Bird 1949, p. 74.

- Turner 2007, p. 13.

- Dodd 2011, p. 404.

- Dodd 2011, pp. 405–407.

- Bird 1949, pp. 96–97.

- Ross 1956, p. 571 n. 1..

- Tuck 1973, p. 60.

- Bird 1949, p. 12.

- Barron 2000, p. 148.

- Barron 2000, p. 142 n. 57.

- Bird 1949, p. 29.

- Coleman 1969, pp. 187, 188.

- Barron 1969, p. 203.

- Woodger 1993b.

- Coleman 1969, p. 193.

- Strohm 2015, p. 151.

- Sumption 2012, p. 636.

- Dodd 2011, p. 414.

- Myers 2009, p. xvii.

- Strohm 2015, p. 173.

- Shakespeare 1994, p. 197.

- Muir 2014, p. 48.

- Saul 2008, p. 144.

- Gransden 1996, p. 162.

- Wylie 1884, p. 113 + n..

- Madison Davis & Frankforter 2004, p. 246.

- Mortimer 2008, p. 212.

- Saul 1997, p. 425 n.104.

- Rawcliffe 1993c.

- Rawcliffe 1993e.

- Woodger 1993a.

Sources

- Barker, J. (2014). England, Arise: The People, the King and the Great Revolt of 1381. London: Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-0-7481-2788-7.

- Barron, C. M. (1969). "Richard Whittington: The Man Behind the Myth". In Hollaender, A. E. J.; Kellaway, W. (eds.). Studies in London History Presented to Philip E. Jones. London: Hodder and Stoughton. pp. 197–248. OCLC 220501191.

- Barron, C. M. (1970). The Government of London and its Relations With the Crown 1400–1450 (PhD thesis). London: Queen Mary College. OCLC 53645536.

- Barron, C. M. (1971). "Richard II and London". In Barron, C. M.; du Boulay, F. R. H. (eds.). The Reign of Richard II: Essays in Honour of May McKisack. London: Athlone Press. pp. 173–201. ISBN 9780485111309.

- Barron, C. M. (1981). Revolt in London: 11th to 15th June 1381. London: Museum of London. ISBN 978-0904818055.

- Barron, C. M. (1999). "Richard II and London". In Goodman, A.; Gillespie, J. L. (eds.). Richard II: The Art of Kingship. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 129–154. ISBN 0-19-820189-3.

- Barron, C. M. (2000). "London 1300–1540". In Palliser, D. M.; Clark, P.; Daunton, M. J. (eds.). Cambridge Urban History of Britain 600-1540. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 395–400. ISBN 0521444616.

- Barron, C. M. (2005). London in the Later Middle Ages: Government and People 1200–1500. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928441-2.

- Beaven, A. P. (2018). The Aldermen of the City of London (repr. ed.). London: FB&C Ltd. ISBN 978-0297995432.

- Besant, W. (1881). Sir Richard Whittington: Lord Mayor of London. London: G.P. Putnam's sons. OCLC 457846665.

- Billington, S. (1990). "Butchers and Fishmongers: Their Historical Contribution to London's Festivity". Folklore. 101: 97–103. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1990.9715782. OCLC 1015879463.

- Bird, R. (1949). The Turbulent London of Richard II. London: Longman. OCLC 644424997.

- Bolton, J. L. (1981). "London and the Peasants' Revolt". The London Journal: A Review of Metropolitan Society Past and Present. 7. OCLC 993072319.

- Bolton, J. L. (1986). "The City and the Crown 1456–61". The London Journal: A Review of Metropolitan Society Past and Present. 12. OCLC 993072319.

- Brown, E. (1979). "Chaucer, the Merchant, and Their Tale: Getting Beyond Old Controversies: Part II". The Chaucer Review. 13. OCLC 423575825.

- Bruce, M. L. (1998). The Usurper King: Henry of Bolingbroke, 1366–99. Guildford: The Rubicon Press. ISBN 978-0948695629.

- Coleman, O. (1969). "The Collectors of Customs in London under Richard II". In Hollaender, A. E. J.; Kellaway, W. (eds.). Studies in London History Presented to Philip E. Jones. London: Hodder and Stoughton. pp. 181–194. OCLC 220501191.

- Colson, J. (2014). "London's Forgotten Company? Fishmongers, their Trade and their Networks in Later Medieval London". In Barron, C. M.; Sutton, A.F. (eds.). The Medieval Merchant: Proceedings of the 29th Harlaxton Medieval Symposium. Donnington: Shaun Tyas. pp. 20–40. ISBN 978-0948695629.

- Davies, R. G. (1971). "Some Notes from the Register of Henry De Wakefield, Bishop of Worcester, on the Political Crisis of 1386-1388". The English Historical Review. 86 (340). OCLC 925708104.

- Dobson, R. B. (1983). Williams, G. A. (ed.). The Peasants' Revolt of 1381. (History in Depth) (2nd ed.). London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0333255056.

- Dodd, G. (2011). "Was Thomas Favent a political pamphleteer? Faction and politics in later fourteenth-century London". Journal of Medieval History. 37 (4): 405, 407. doi:10.1016/j.jmedhist.2011.09.003. OCLC 39167361. S2CID 154945866.

- Duls, L. D. (1975). Richard II in the Early Chronicles. The Hague: Walter De Gruyter Inc. ISBN 902793326X.

- Ellis, R. (2012). Verba Vana: Empty Words in Ricardian London (PhD thesis). Vol. 1. Queen Mary, University of London.

- Favent, T. (2002). "History or Narration Concerning the Manner and Form of the Miraculous Parliament at Westminster". In Steiner, E.; Barrington, C. (eds.). The Letter of the Law: Legal Practice and Literary Production in Medieval England. Translated by Galloway, A. London: Cornell University Press. pp. 231–252. ISBN 0-8014-8770-6.

- Firth Green, R. (2002). A Crisis of Truth: Literature and Law in Ricardian England. The Middle Ages Series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812218091.

- Given-Wilson, C. (2016). Henry IV. Padstow: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300154191.

- Given-Wilson, C.; Brand, P.; Phillips, S.; Ormrod, M.; Martin, G.; Curry, A.; Horrox, R., eds. (2005a). "Introduction: Edward III: June 1369". British History Online. Parliament Rolls of Medieval England. Woodbridge. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- Given-Wilson, C.; Brand, P.; Phillips, S.; Ormrod, M.; Martin, G.; Curry, A.; Horrox, R., eds. (2005b). "Introduction: Richard II: October 1386". British History Online. Parliament Rolls of Medieval England. Woodbridge. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- Given-Wilson, C.; Brand, P.; Phillips, S.; Ormrod, M.; Martin, G.; Curry, A.; Horrox, R., eds. (2005c). "Introduction: Richard II: September 1388". British History Online. Parliament Rolls of Medieval England. Woodbridge. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- Goddard, R. (2014). "The Merchant". In Rigby, S. H. (ed.). Historians on Chaucer: The General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 170–186. ISBN 9780199689545.

- Goodman, A. (1971). The Loyal Conspiracy: The Lords Appellant Under Richard II. London: University of Miami Press. ISBN 0870242156.

- Gransden, A. (1996). Historical Writing in England: c. 1307 to the Early Sixteenth Century. Vol. II (repr. ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415152372.

- Gray, D. (2004). "Chaucer, Geoffrey (c.1340–1400)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5191. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hanrahan, M. (2003). "Defamation as Political Contest During the Reign of Richard II". Medium Ævum. 72 (2): 259–276. doi:10.2307/43630497. JSTOR 43630497. OCLC 48384230.

- Hatfield, E. (2015). London's Lord Mayors: 800 Years of Shaping the City. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445650302.

- Hicks, M. A. (2002). The Wars of the Roses. Totton: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18157-9.

- Hilton, R. H.; Fagan, H. (1950). The English Rising of 1381. London: Lawrence and Wishart Ltd. OCLC 759749287.

- Hope, V. (1989). My Lord Mayor: 800 Years of London's Mayoralty. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-79519-8.

- Kuhl, E. P. (1914). "Some Friends of Chaucer". Publications of the Modern Language Association. 29 (2): 270–276. doi:10.2307/457079. JSTOR 457079. OCLC 860396590.

- Lobel, M. D. (1990). The British Atlas of Historic Towns: City of London from Prehistoric Times to c.1520. Vol. III. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198229797.

- Madison Davis, J.; Frankforter, D. A. (2004). The Shakespeare Name Dictionary. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-87571-8.

- McCall, J. P.; Rudisill, G. (1959). "The Parliament of 1386 and Chaucer's Trojan Parliament". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 58 (2). OCLC 22518525.

- McKisack, M. (1991). The Fourteenth Century (repr. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192852507.

- Mortimer, I. (2008). The Fears of Henry IV: The Life of England's Self-Made King. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-1844135295.

- Muir, K. (4 April 2014). The Sources of Shakespeare's Plays. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-83341-3.

- Myers, A. R. (2009). Chaucer's London: Everyday Life in London 1342–1400. Stroud: Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-1222-5.

- Nightingale, P. (1989). "Capitalists, Crafts and Constitutional Change in Late Fourteenth-Century London". Past & Present. 124: 3–35. doi:10.1093/past/124.1.3. OCLC 664602455.

- Noorthouck, J. (1773). "Richard II to the Wars of the Roses". A New History of London Including Westminster and Southwark. Vol. I. London: R. Baldwin. pp. 75–94. OCLC 59484976.

- Oliver, C. (2010). Parliament and Political Pamphleteering in Fourteenth-century England. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-903153-31-4.

- Oman, C. W. C. (1906). The Great Revolt of 1381. London: Clarendon Press. OCLC 7113198358.

- Postan, M. M. (1972). The Medieval Economy and Society (repr. ed.). London: Penguin. OCLC 7113198358.

- Prescott, A. (1981). "London and the Peasants' Revolt: A Portrait Gallery". The London Journal: A Review of Metropolitan Society Past and Present. 7. OCLC 993072319.

- Rawcliffe, C. R. (1993a). "Fastolf, Hugh (d.c.1392), of Great Yarmouth and Caister, Norf. and London". The History of Parliament Online. Boydell and Brewer. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- Rawcliffe, C. R. (1993b). "Turk, Sir Robert (d.1400), of London and Hitchin, Herts". The History of Parliament Online. Boydell and Brewer. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- Rawcliffe, C. R. (1993c). "Wade, John I, of London". The History of Parliament Online. Boydell and Brewer. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- Rawcliffe, C. R. (1993d). "Wroth, John (d.1396), of Enfield, Mdx. and Downton, Wilts". The History of Parliament Online. Boydell and Brewer. Archived from the original on 3 May 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- Rawcliffe, C. R. (1993e). "Exton, Thomas (d.1420), of London". The History of Parliament Online. Boydell and Brewer. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- Réville, A. (1898). Le Soulèvement des Travailleurs d'Angleterre en 1381. Paris: A. Picard et fils. OCLC 565123831.

- Rich, E. E. (1933). "List of Officials of the Staple of Westminster". Cambridge Historical Journal. 4 (2): 192–193. doi:10.1017/S1474691300000500. OCLC 67139422.

- Riley, H. T. (1861). Liber albus: The White Book of the City of London. London: John Russell Smith. OCLC 728263266.

- Robertson, D. W. (1968). Chaucer's London. (New Dimensions in History). London: John Wiley & Son. ISBN 9780471727309. OCLC 1015342036.

- Roskell, J. S. (1984). The Impeachment of Michael de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk in 1386: In the Context of the Reign of Richard II. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-0963-1.

- Ross, C. D. (1956). "Forfeiture for Treason in the Reign of Richard II". The English Historical Review. 71. OCLC 51205098.

- Round, J. H. (1886). "Brembre, Sir Nicholas (d.1388)". In Leslie, L. (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. VI. London: Smith, Elder. pp. 256–258. OCLC 636834994.

- Sanderlin, S. (1988). "Chaucer and Ricardian Politics". The Chaucer Review. 22 (3): 171–184. OCLC 43359050.

- Saul, N. (1997). Richard II. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07003-9.

- Saul, N. (2008). Fourteenth Century England. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-387-1.

- Shakespeare, W. (1994). The Complete Oxford Shakespeare: Histories. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-818272-6.

- Sharpe, R. R., ed. (1907). "Introduction". Calendar of Letter-Books of the City of London. Vol. H (1375–1399). London: H.M.S.O. pp. lii. OCLC 257422744.

- Sherborne, J. (1994). Tuck, J. A. (ed.). War, Politics and Culture in Fourteenth-Century England. London: Hambledon. ISBN 1-85285-086-8.

- Steel, A. (1974). "The Collectors of the Customs in the Reign of Richard II". In Hearder, H.; Loyn, H. R. (eds.). British Government and Administration: Studies Presented to S. B. Chrimes. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. pp. 27–39. ISBN 0708305385.

- Strohm, P. (2004a). "Exton, Nicholas (d. 1402)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/52173. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Strohm, P. (2004b). "Northampton, John (d. 1398)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20322. Archived from the original on 4 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Strohm, P. (2006). Hochon's Arrow: The Social Imagination of Fourteenth-Century Texts. (Princeton Legacy Library). Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691015019.

- Strohm, P. (2015). The Poet's Tale: Chaucer and the year that made The Canterbury Tales. London: Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-84765-899-9.

- Sumption, J. (2012). The Hundred Years' War III: Divided Houses. Croydon: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-24012-8.

- Tuck, J. A. (1973). Richard II and the English Nobility. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 0-7131-5708-9.

- Tuck, J. A. (2004). "'Pole, Michael de la, first earl of Suffolk (c.1330–1389)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22452. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Turner, M. M. (2007). Chaucerian Conflict: Languages of Antagonism in Late Fourteenth-Century London. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199207893.

- Victoria County History (2001). A History of the County of Essex: Lexden Hundred (Part) Including Dedham, Earls Colne and Wivenhoe. Vol. X. London: VCH Ltd. ISBN 978-0197227954.

- Welch, C. (1916). History of the Cutlers' Company of London and of the Minor Cutlery Crafts, with Biographical Notices of Early London Cutlers. Vol. I. London: Cutlers' Company. OCLC 792753718.

- Woodger, L. S. (1993a). "Lisle, Sir John (1366–1408), of Wotton, I.o.W. and Thruxton, Hants". The History of Parliament Online. Boydell and Brewer. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- Woodger, L. S. (1993b). "Maple, William (d.c.1399), of Southampton". The History of Parliament Online. Boydell and Brewer. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- Wylie, J. H. (1884). History of England Under Henry the Fourth. Vol. I (1399–1404). London: Longmans, Green and co. OCLC 923542025.