Nicholas Said

Nicholas Said (born Mohammed Ali ben Sa'id, 1836–1882) was a traveler, translator, soldier, and author.

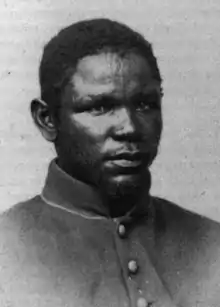

Nicholas Said | |

|---|---|

Nicholas Said, taken in Boston in July 1863 | |

| Birth name | Mohammed Ali ben Said |

| Born | 1836 Kukawa, Bornu Empire |

| Died | 1882 (aged 45–46) Brownsville, Tennessee, United States of America |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service/ | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1863–1865 |

| Rank | Sergeant |

| Unit | 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Life

Born in Kukawa, Bornu Empire, Said fell victim to the Trans-Saharan slave trade. His father, Barca Gana,[1] was a famous general and his unusual aptitude for learning languages, however, led to the elevation of his social position.[2] Having learned Arabic in his youth in Central Africa, he quickly learned the Ottoman Turkish language of his enslavers. Demonstrating proficiency in Russian, he became the servant of Russian Prince Alexander Sergeyevich Menshikov, who provided him with a French tutor after recognizing his exceptional linguistic abilities. By the time of his 1872 memoirs, he reported familiarity or fluency with the Kanuri, Mandara, Arabic, Turkish, Russian, German, Italian and French languages, as well as some experience with Armenian. Said traveled widely in Africa, the Middle East, Europe, and the Russian Empire, later venturing to the Caribbean, South America, Canada, and the United States. In his account of his life and travels, Said decried the aggression of Usman dan Fodio against his homeland, described his pilgrimage to Mecca, reminisced about a chance encounter with the Czar, and reflected on his conversion from Islam to Christianity in Riga.[3]

From 1863 to 1865, Said served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Unlike most of the African Americans who served in the United States Army during the war, neither Said nor any of his ancestors had ever been enslaved in the United States. Rather, Said voluntarily immigrated to the United States and then volunteered to fight in the war.[4] Near the end of the war, he requested attachment to the Hospital Department so that he could take up the study of medicine. An 1867 journalist's account suggests that, after the war, Said fell in love with an American woman and married her.[5] They are reported to have settled in St. Stephens, Alabama, where Said wrote his memoirs.[6] Said's later life is unclear, but one account has him dying in Brownsville, Tennessee.[7]

Because he was living in the Reconstruction-era South, he did not disclose his service in the United States Army in his memoirs.[2] A trophy photograph of Said posing in his U.S. Army uniform, during his attachment to the 55th United States Colored Infantry Regiment, survives.[8][9]

Family in Bornu

Said described himself as being a Kanouri speaker born in "Kouka" (now Kukawa), near Lake Chad, the son of General (Katzalla) Barca Gana and a Mandara woman named Dalia. Said was raised primarily by his mother. According to Said, his father had four wives, and was "large, tall, and well proportioned; resembling more a giant than an ordinary man." "My father greatly distinguished himself under our immortal King Mohammed El Amin Ben Mohammed El Kanemy, the Washington of Bornou... He was the terror of... the enemies of our Country, and wherever he appeared the enemy fled..."

The military prowess of Said's father is described by an English traveler who had the opportunity to witness Barca Gana in combat. Dixon Denham accompanied a military expedition in which the forces of Bornu under Barca Gana were joined with those of an Arab slave-raiding army and those of the Sultan of Mandara. In combat against the forces of the Sokoto Caliphate, Denham reported that "A Fellatah chief with his own hand brought down four Bornu warriors, when Barca Gana, whose strength was gigantic, threw a spear from a distance of thirty-five yards and laid the pagan low..."[10] Denham's report added of Barca Gana's heroism, "The Bornu general had three horses killed under him by poisoned arrows." While Denham attributes his survival to Barca Gana's prowess in combat, he also noted that Barca Gana had to be dissuaded from leaving the wounded white man behind, as the general did not want to divert military resources for the preservation of an adventurer who was not even a Muslim. Advised by one of his party that God seemed to want Denham preserved, Barca Gana delivered Denham to safety.

Nicholas Said was not born until years after his father's wartime episode against the Sokoto Caliphate, recalled by Denham. (Jules Verne would later retell the story in his novel Five Weeks in a Balloon, but he cast Denham as the hero rather than Barca Gana, despite Denham's only surviving because Fulani warriors wanted to seize his clothing to use as "proof" that Christians were being used to fight in the Bornu-Mandara army[11]: 109 ) Said did report his first encounter with a white man, whom he identified as the German researcher Heinrich Barth:

"When I was about twelve years old, a large caravan arrived from Fezzan, and it was said a Sârâ (white man) was one of the party. This raised a great excitement, particularly among us children, for we had heard fabulous tales concerning them. For example, we were told that the whites were cannibals, and all the slaves that they bought were for no other but culinary purposes. Sure enough, there arrived a white man, and the King assigned him a dwelling situated in East Kouka... The first time I saw him was one day when he was in the market, outside of Kouka, and I ran from him."[12]

References

- Calbreath, Dean (2003). The Sergeant: The Incredible Life of Nicholas Said: Son of an African General, Slave of the Ottomans, Free Man Under the Tsars, Hero of the Union Army. Pegasus Books. ISBN 9781639363254.

- Paul E. Lovejoy. Mohammed Ali Nicholas Sa'id: From Enslavement to American Civil War Veteran

- "Nicholas Said, 1836-1882. The Autobiography of Nicholas Said, A Native of Bournou, Eastern Soudan, Central Africa". Docsouth.unc.edu. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Safet Dabovic. Out of Place: The Travels of Nicholas Said. Criticism, Vol. 54, No. 1., pp. 59-83

- "A Native of Bornoo" (PDF). Tubmaninstitute.ca. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "Summary of the Autobiography of Nicholas Said, A Native of Bournou, Eastern Soudan, Central Africa". Archived from the original on 2019-06-26. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

- Allan D. Austin. "Mohammed Ali Ben Said: Travels on Five Continents." Contributions in Black Studies, Volume 12, Article 15: October 2008

- Paul Lovejoy. Jihad in West Africa During the Age of Revolutions. pp. 242-3; 258, 2016, ISBN 978-0821422410

- "MHS Collections Online: Nicholas Said". Masshist.org. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Charles Henry Eden. "Africa, Seen Through Its Explorers" pp. 135-6, 2010, ISBN 978-1166532109

- Njeuma, Martin Zachary (1969). The rise and fall of Fulani rule in Adamawa 1809-1901 (phd thesis). SOAS University of London.

- Autobiography, pp. 25-6

Sources

- Calbreath, Dean (2023), The Sergeant: The Incredible Life of Nicholas Said: Son of an African General, Slave of the Ottomans, Free Man Under the Tsars, Hero of the Union Army

- Egerton, Douglas (2017). Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments That Redeemed America. New York : Basic Books.