Twenty-Four Eyes

Twenty-Four Eyes (二十四の瞳, Nijū-shi no hitomi) is a 1954 Japanese drama film directed by Keisuke Kinoshita, based on the 1952 novel of the same name by Sakae Tsuboi.[1] The film stars Hideko Takamine as a young schoolteacher who lives during the rise and fall of Japanese nationalism in the early Shōwa period, and has been noted for its anti-war theme.[2]

| Twenty-Four Eyes | |

|---|---|

_poster.jpg.webp) Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Keisuke Kinoshita |

| Screenplay by | Keisuke Kinoshita |

| Based on | Twenty-Four Eyes by Sakae Tsuboi |

| Produced by | Ryotaro Kuwata |

| Starring | Hideko Takamine |

| Cinematography | Hiroshi Kusuda |

| Edited by | Yoshi Sugihara |

| Music by | Chuji Kinoshita |

| Distributed by | Shochiku |

Release date |

|

Running time | 154 minutes |

| Language | Japanese |

Twenty-Four Eyes was released in Japan by Shochiku on 15 September 1954, where it received generally positive reviews and was a commercial success.[3] It received numerous awards, including the Blue Ribbon Award, the Mainichi Film Award and the Kinema Junpo Award for Best Film of 1954, and the Golden Globe Award.[4][5][6]

Plot

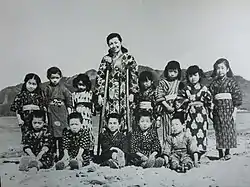

On 4 April 1928, young schoolteacher Hisako Ōishi arrives on the island of Shōdoshima, where she will be teaching a class of first grade students from the nearby village. Ōishi is introduced to her class of twelve students: Isokichi, Takeichi, Kichiji, Tadashi, Nita, Matsue, Misako, Masuno, Fujiko, Sanae, Kotoe, and Kotsuru. Because her surname Ōishi (大石) can be translated as "Big Stone", but she is shorter in stature than her predecessor, the children address her as "Miss Pebble" (小石, Oishi).[7] She teaches the children how to sing songs, and plays outside with them. Most of the children have to care for younger siblings or help their parents with farming or fishing after school. Because Ōishi rides a bicycle and wears a Western suit, the adult villagers are initially apprehensive towards her.

On 1 September, the class goes to the seashore, where some of the students play a practical joke on Ōishi by causing her to fall into a hole in the sand. The fall injures one of her legs, and she takes a leave of absence. A substitute teacher takes her place, but the children are not as receptive to him as they were to Ōishi. One day after lunch, the students sneak away from their homes and journey on foot to go visit Ōishi. They spot her riding in a bus, and she invites them to her house, where they have a large meal; later, the children's parents send Ōishi gifts as thanks for treating them. Because of her injury, Ōishi is transferred from the schoolhouse to the main school, where teachers instruct students in fifth grade and above.

By 1933, Ōishi is engaged to a ship engineer, and her original students are now sixth graders. Matsue's mother gives birth to another girl but dies in the process, leaving Matsue to care for the child. Soon after, the baby dies as well, and Matsue leaves Shōdoshima. Ōishi learns that a fellow teacher, Mr. Kataoka, has been arrested on suspicion of being "a Red". Kataoka was suspected of having a copy of an anti-war anthology printed by a class taught by a friend of his in Onomichi. Ōishi notes that she shared stories from that anthology with her own students after a copy was sent to the school. The principal warns Ōishi against discussing politics with her class, and burns the anthology.

In October, Ōishi and her class take a field trip to Ritsurin Park in Takamatsu, as well as to the Konpira Shrine. Ōishi goes into town and encounters Matsue, who is now working at a restaurant as a waitress. Back at school, Ōishi has her students write down their hopes for the future; Sanae dreams of becoming a teacher, while Fujiko, whose family is impoverished, feels hopeless. Kotoe drops out of school to help her mother at home; Masuno wants to attend a conservatory, but her parents disapprove; the male students in the class want to become soldiers. Ōishi is reprimanded by the principal for not encouraging the boys in their military aspirations. Some time later, Ōishi, who is now pregnant, decides to resign from teaching.

In 1941, Ōishi visits Kotoe, who now has tuberculosis. Ōishi has given birth to three children: Daikichi, Namiki, and Yatsu. Misako has been married; Sanae is now a teacher at the main school; Kotsuru is an honors graduate in midwifery; Fujiko's family went bankrupt; Kotsuru works at a café in Kobe; Masuno works at her parents' restaurant; and the male students have all joined the military. As time passes, Ōishi's mother dies, and Ōishi's husband is killed.

On 15 August 1945, Emperor Hirohito announces the surrender of Japan at the end of World War II. Ōishi's daughter Yatsu later dies after falling from a tree trying to pick persimmons.

On 4 April 1946, Ōishi, now struggling financially, returns to teaching. Among the students in her new class are Makoto, the younger sister of Kotoe, who has died; Chisato, Matsue's daughter; and Katsuko, Misako's daughter. Ōishi reunites with an adult Misako, and they visit the graves of Tadashi, Takeichi, and Nita, all of whom were killed during the war. Misako, along with Sanae, Kotsuru, and Masuno, hosts a party for Ōishi at Masuno's residence. They are joined by Isokichi, who was blinded in the war, and Kichiji. The students present Ōishi with a new bicycle to ride to school.

Cast

- Hideko Takamine as Hisako Ōishi

- Hideki Goko as Isokichi Okada in first grade. His nickname is "Sonki".

- Hitoshi Goko as Isokichi in sixth grade

- Takahiro Tamura as adult Isokichi

- Itsuo Watanabe as Takeichi Takeshita in first grade

- Shiro Watanabe as Takeichi in sixth grade

- Makoto Miyagawa as Kichiji Tokuda in first grade. His nickname is "Kit-chin".

- Junichi Miyagawa as Kichiji in sixth grade

- Yasukuni Toida as adult Kichiji

- Takeo Terashita as Tadashi Morioka in first grade. His nickname is "Tanko".

- Takeaki Terashita as Tadashi in sixth grade

- Kunio Satō as Nita Aizawa in first grade. His nickname is "Nikuta".

- Takeshi Satō as Nita in sixth grade

- Yuko Ishii as Masuno Kagawa in first grade. Her nickname is "Ma-chan".

- Shisako Ishii as Masuno in sixth grade

- Yumeji Tsukioka as adult Masuno

- Yasuyo Koike as Misako Nishiguchi in first grade. Her nickname is "Mi-san".

- Koike also plays Katsuko, Misako's daughter.

- Akiko Koike plays Misako in sixth grade

- Toyoko Shinohara plays adult Misako

- Setsuko Kusano as Matsue Kawamoto in first grade. Her nickname is "Mat-chan".

- Sadako Kusano as Matsue in sixth grade

- Kusano as Matsue's daughter Chisato

- Sadako Kusano as Matsue in sixth grade

- Kaoru Kase as Sanae Yamaishi in first grade

- Kayoko Kase as Sanae in sixth grade

- Toshiko Kobayashi as adult Sanae<

- Yumiko Tanabe as Kotsuru Kabe in first grade

- Naoko Tanabe as Kotsuru in sixth grade

- Mayumi Minami as adult Kotsuru

- Ikuko Kanbara as Fujiko Kinoshita in first grade

- Toyoko Ozu as Fujiko in sixth grade

- Hiroko Uehara as Kotoe Katagiri in first grade

- Uehara also plays Makoto, Kotoe's younger sister

- Masako Uehara plays Kotoe in sixth grade

- Yoshiko Nagai plays adult Kotoe

- Chishū Ryū as the male primary school teacher

- Toshio Takahara as Chiririn'ya

- Shizue Natsukawa as Ōishi's mother

- Kumeko Urabe as the teacher's wife

- Nijiko Kiyokawa as the shopkeeper

- Chieko Naniwa as the restaurant owner

- Ushio Akashi as the headmaster

- Hideyo Amamoto as Ōishi's husband

- Tokuji Kobayashi as Matsue's father

- Toshiyuki Yashiro as Daikichi

Themes

American author David Desser wrote of the film that "Kinoshita desires to make the basic decency of one woman [Ōishi] stand in opposition to the entire militarist era in Japan."[8] Japanese film theorist and historian Tadao Sato wrote that "Twenty-Four Eyes evolved to represent Japanese regrets over the wars in China and the Pacific and stood in symbolic opposition to the impending return to militarism."[3] Sato added that the film "implies that the honest citizens of Japan were only victims of trauma and sorrow and fundamentally innocent of any culpability for the war. [...] Had the movie assigned responsibility for the war to all Japanese people, opposition would have arisen, and it might not have become such a box-office hit."[3]

Film scholar Audie Bock referred to Twenty-Four Eyes as being "undoubtedly a woman's film, honoring the endurance and self-sacrifice of mothers and daughters trying to preserve their families", and called it "a meticulously detailed portrait of what are perceived as the best qualities in the Japanese character: humility, perseverance, honesty, love of children, love of nature, and love of peace."[2] Bock wrote that "The resonance of Twenty-Four Eyes for audiences then and now is that Miss Oishi speaks for countless people the world over who never want to see another father, son, or brother die in a war for reasons they do not understand", and posited that the film's anti-war message is "aimed more directly at Japan" compared to films with a similar message by Yasujirō Ozu or Akira Kurosawa.[2]

In an analysis of the film, Christopher Howard wrote: "From a feminist perspective, there is certainly great sympathy with the young girls forced out of school and into menial work by their parents [...] As a pacifist and leftist sympathizer, however, Kinoshita raises stronger political questions in an episode in which Miss Oishi displays sympathy with a fellow teacher accused of communist connections."[9] He notes that "she even tries introducing some elements of Marxism into her class teaching. At a time in which the Japanese Teaching Union was the source of a great deal of radical activity, Twenty-Four Eyes is not the only film making the connection between teaching and left-wing thought, and a number of independent films from the period also had more sustained anti-military and communist sympathies."[9]

Reception

Twenty-Four Eyes was a popular film in Japan upon its release in 1954.[7]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 60% based on five reviews, with an average rating of 6.69/10.[10] In 2006, Alan Morrison of Empire gave the film a score of four out of five stars, calling it "Sentimental but sincere."[11] In 2008, Jamie S. Rich of DVD Talk praised the film's ensemble of child actors and its emotional weight, writing that "If you don't tear up at least a couple of times in Twenty-Four Eyes, you apparently have rocks where the rest of us have brains and hearts."[7] Rich called the film "an effective lesson in how the hopes and dreams of our youngest citizens and the opportunities they are given to pursue them are essential to the survival of any society."[7] Fernando F. Croche of Slant Magazine gave the film two-and-a-half out of four stars, calling it "alternately endearing and overbearing to modern eyes and ears" but "reportedly a soothing experience" for Japanese viewers still suffering from the effects of World War II when the film was released.[12]

Awards

- Blue Ribbon Award for Best Film and Best Screenplay[4]

- Mainichi Film Award for Best Film, Best Director and Best Screenplay[5]

- Kinema Junpo Award for Best Film

- Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign-Language Foreign Film[6]

- Henrietta Award at the 5th Annual World Film Favorite Festival[13]

Twenty-Four Eyes ranked #6 on the 2009 All Time Best Japanese Movies list by readers of Kinema Junpo.[14]

Home media

On 20 February 2006, Twenty-Four Eyes was released on DVD in the United Kingdom by Eureka Entertainment, as part of their Masters of Cinema line of home video releases, containing an essay by film historian Joan Mellen.[15] In August 2008, the film was released on DVD by the Criterion Collection which included an essay by Audie Bock and excerpts from an interview with Kinoshita.[7][16]

A Japanese Blu-ray edition of the film was released by TCEntertainment in 2012.[17]

Remake and other adaptations

A color remake of the film, directed by Yoshitaka Asama and known in English as Children on the Island, was released in 1987.[18]

Besides the movie versions, there have also been numerous TV drama recreations, including an animated version in 1980.[19]

References

- Kittaka, Louise George (11 March 2017). "'Twenty-four Eyes': A quiet commentary on the inhumanity of war". The Japan Times. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Bock, Audie (18 August 2008). "Twenty-Four Eyes: Growing Pains". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- West, Philip; Levine, Steven I.; Hiltz, Jackie, eds. (1998). America's Wars in Asia: A Cultural Approach to History and Memory. M. E. Sharpe. p. 61. ISBN 0-7656-0236-9.

- "1954 Blue Ribbon Awards" (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- "1954 Mainichi Film Awards" (in Japanese). Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- "Twenty-Four Eyes". Golden Globe Awards. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- Rich, Jamie S. (15 August 2008). "Twenty-Four Eyes - Criterion Collection". DVD Talk. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Desser, David (1988). Eros Plus Massacre: An Introduction to the Japanese New Wave Cinema. Indiana University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0253204691.

- Berra, John, ed. (2012). Directory of World Cinema: Japan 2. Intellect Ltd. pp. 322–323. ISBN 978-1-84150-551-0.

- "Nijushi no Hitomi (Twenty-Four Eyes)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Morrison, Alan (31 March 2006). "Twenty-Four Eyes Review". Empire. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Croce, Fernando F. (18 August 2008). "Review: Twenty-Four Eyes". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- Anderson, Joseph L.; Richie, Donald (1983). The Japanese Film: Art and Industry (Expanded ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0691007922.

- "Japanese Movies All Time Best 200 (Kinejun Readers)". mubi.com. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- "Twenty-Four Eyes (DVD)". Eureka. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- "Twenty-Four Eyes (1954)". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- "Kinoshita Keisuke 100th Anniversary Twenty-Four Eyes (Nijushi no Hitomi) Blu-ray (1987 Edition) [Blu-ray]". CD Japan. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- Paietta, Ann C. (2007). Teachers in the Movies: A Filmography of Depictions of Grade School, Preschool and Day Care Educators, 1890s to the Present. McFarland & Company. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-7864-2938-7.

- "二十四の瞳 (Twenty-Four Eyes)". テレビドラマデータベース (TV Drama Database) (in Japanese). Retrieved 31 July 2023.

External links

- Twenty-Four Eyes at IMDb

- Twenty-Four Eyes at AllMovie

- Twenty-Four Eyes at Rotten Tomatoes

- "二十四の瞳 (Nijū-shi no Hitomi)" (in Japanese). Japanese Movie Database. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- Kittaka, Louise George (8 June 2018). "Shodoshima: Movie history with a side of olives". The Japan Times. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Klinowski, Jacek; Garbicz, Adam (2016). Cinema, the Magic Vehicle: A Comprehensive Guide (Volume Two: 1951–1963). PlanetRGB Limited. p. 159. ISBN 9781513607238.