Nile boat

The Nile River is a major resource for the people living along it, especially thousands of years ago. The El Salha Archaeological Project discovered an abundance of evidence of an ancient boat that traveled the Nile River dating back to 3,000 years ago. Pictographs and pebble carvings were uncovered, indicating a boat more advanced than a simple canoe. This evidence of a progressed Nile boat includes a steering system which may have been used in the Nile for fishing and transportation.

Discovery

The earliest evidence for an ancient boat on the Nile is a rock art pictograph that dates to the Mesolithic. The El Salha Archaeological Project of the Italian Institute for African and Oriental Studies has been working in the central Sudan since the fall of 2000. The project's priority is the archeology of the Mesolithic and Neolithic cultures of this region of the Nile Valley. Of great interest to maritime archeology is an elongated burial mound on the west bank of the Nile, 25 km south of Omdurman. Beneath this Post-Meroitic burial and disturbed deposits was a compact, homogeneous layer of the Khartoum Mesolithic. Diagnostic gastropods were in this layer and radiocarbon dating delineates a time span of 7050 to 6820 BC.

An important artifact that speaks to the early history of boat design and ship building was found in the Khartoum Mesolithic layer. A recognizable outline of Nile boat had been cut into a granite pebble.[1] This is the oldest known representation of a Nile boat, and the oldest depiction of a boat that is more advanced in design than a canoe. The dating of this pictograph pushes back the earliest evidence for Nile boats by 3,000 years.

Boat design / steering

Some detail and aspects of boat construction can be inferred from the image on the granite pebble, as first reported by D. Usai and S. Salvatori in December, 2007. The back half of the boat image is in the best state of preservation. A steering system and cabin are situated at the approximate center of the boat. A composite steering system can be discerned with a tiller placed a t a greater than 45° angle with a long pole ending in an ovoid blade. Tiller and pole with blade are fixed to the top of a vertical yoke. Boat and steering system design resemble those painted on the walls of Badarian huts and pottery jars. There are similarities with some boats depicted in rock engravings in Nubia (Sudan); and those painted on walls and pottery in the Gerzeh culture and Naqada culture of Predynastic Egypt.

“In particular the image of a steering gear fixed to a vertical pole inserted in the stern upper hull can be found in boat rock engravings from the Abka region in Sudanese Nubia; and from Akkad which is south of the third Cataract on the left bank of the Nile in the Northern Dongola Reach. The blade strongly resembled those of the boat of El Khab. This kind of composite helm was still in use on Egyptian ships built during the New Kingdom. The dome-like cabin on the upper hull is also a well known feature on boat representations dating to the Gerzean and Predynastic periods in Egypt and Nubia.”[2] The Khartoum Mesolithic boat may be said to represent the end of important, coordinated developments in boat design. The specific features of the boat depicted on the rock from the 16 D-5 site must have been designed earlier in the Nubian Mesolithic. As this approach to hull design, cabin layout and steering mechanism are found on boats thousands of years later, it had been judged the best possible architecture for small and medium size Nile boats during the Khartoum Mesolithic. As the first and best choice in Nile boat nautical architecture, this design persisted in boat building tradition for several thousand years. Slight modifications would produce either a fishing or cargo boat.

Mesolithic fishing boats

Use of boats on the Nile in the Mesolithic had been proposed by W. Van Neerand in 1989.[3] and by Peters in 1991 [4] and 1993.[5] Studies of the ichthyo-fauna in Mesolithic sites in Central Sudan and lower Atbara published in 1993 led Peters to postulate that well designed Nile boats were used to fish for adults of the open water species Synodotis, Bagrus and Lates on a regular basis as opposed to fortuitous situations that occur in seasonal flood pools. Lates is the infamous Nile Perch that can grow to 6'7” (2m) in length and 200 kg (440 lb) in weight. An aggressive fish of this size requires a boat of minimum weight and maneuverability and therefore provides an indirect estimate for the dimensions and weight of Mesolithic fishing boats that plied the Central Sudanese Nile and Lower Atbara. The design of the boat depicted on the rock from the 16 D-5 site, and contextual inference for fishing, also implies a minimal level of navigation skill.

A very important question arises about hull construction. Only two options are known to be available: a hull formed from a large log (tree trunk) or built up as with a papyrus reed boat. True planked hull construction cannot be documented earlier than the 1st Dynasty with the discoveries at Tarkhan of planked hull boards that were re-used as coffin and roof timbers [6] However the architectural features of the Khartoum Mesolithic boat were refined and executed, they received broad acceptance among Egyptian ship builders and were widely utilized in nautical architecture during the next periods of Egyptian history. The limited opportunities provided by the Papyrus reed raft had been transcended.[7] Mankind's ability to utilize the resource opportunities provided by the broad Upper Nile basin, and the large Nile delta of Lower Egypt had taken a quantum leap forward with this 'new' boat design as depicted on the Khartoum Mesolithic pebble.

Naqada II

In Naqada II (3500-3200 BC), there are features of boat design that hearken back to Khartoum Mesolithic boat. A steering system and cabin are situated at the approximate center of the boat. A composite steering system can be discerned with a tiller placed at a greater than 45° angle with a long pole ending in an ovoid blade. Tiller and pole with blade are fixed to the top of a vertical yoke. The tall stem with leaves in the bow of these ships has long puzzled historians of ancient shipbuilding. This structure may be: a) a large branch from a tree species with large leaves; or b) the frond from a large palm tree. Either choice would catch the wind and provide important capability for steering and tacking along the Nile. The Palm branch (symbol) represented long life in ancient Egypt, and the god Huh who deified eternity sometimes carried a palm frond in either hand.

In the Predynastic and Naqada boats, cabins amidships are depicted, indeed appear to be a ubiquitous feature of Egyptian boat building for a long many centuries. The steering system with tiller positioned at a 45° angle can be identified in the stylized art style that abstracts essential features of boat design. On some boats, as depicted on the Sabu-Jaddi rock art site, a pilot stands on the roof of the ship's cabin, apparently to be better positioned to adjust the tall tiller.[8] This portrayal also implies that a larger boat design was an option to Naqada boat builders.

Naqada II boat on pottery vase

Naqada II boat on pottery vase Naqada II boat on pottery vase

Naqada II boat on pottery vase Naqada II boat on pottery vase

Naqada II boat on pottery vase Naqada II boat on pottery vase

Naqada II boat on pottery vase Naqada II boats on pottery vases

Naqada II boats on pottery vases

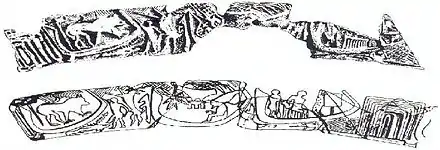

- Naqada boats on the Gebel el-Arak Knife

.jpg.webp)

Egyptian-type bow-shaped boat. Possibly part of the depiction of a naval battle.[10] (Front, 5th register)

Egyptian-type bow-shaped boat. Possibly part of the depiction of a naval battle.[10] (Front, 5th register)

References

- The oldest representation of a Nile boat by D. Usai & S. Salvatori, Antiquity Vol 81 issue 314 December 2007, retrieved July 11, 2008.

- The oldest representation of a Nile boat by D. Usai & S. Salvatori, Antiquity Vol 81 issue 314 December 2007, retrieved July 11, 2008. Additional references, see Aksamit, 1981.

- Van Neerand, W. Fishing along the Prehistoric Nile, in: L. Krzyýaniak & M. Kobusiewicz (ed.) Late Prehistory of the Nile Basin and the Sahara (Studies in African Archaeology Vol. 2): 49-56. Poznan: Poznan Archaeological Museum, 1991. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- Mesolithic Fishing along the Central Sudanese Nile and the Lower Atbara, Sahara 4: 33-40, 1991. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- Mesolithic Fishing along the Central Sudanese Nile and the Lower Atbara, by J. Peters, Sahara 4: 33-40. 1993. Animal exploitation between the fifth and the sixth Cataract c. 8500-7000 BP: a preliminary report on the faunas from El Damer, Abu Darbein and Aneibis, in L.Krzyýaniak, M. Kobusiewicz & J. Alexander (ed.) Environmental Change and Human Culture in the Nile Basin and Northern Africa until the Second Millennium BC (Studies in African Archaeology Vol. 4): 413-9. Poznan: Poznan Archaeological Museum. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- Boats of Egypt Before the Old Kingdom by Steve Vinson, 1987, p.39-81. Retrieved March 16, 2008.

- Papyrus reed boat or "tankwa", Lake Tana by Majestic Moose. Flickr, April 2008, retrieved March 26, 2010. The use of papyrus reed rafts continued and they are still made by fishermen in Ethiopia.

- Léone Allard-Huard: Nil-Sahara.Dialogues rupestres.II.L’homme innovateur, 2000, pp.383-405.

- William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-931464-96-6.

- Shaw, Ian (2019). Ancient Egyptian Warfare: Tactics, Weaponry and Ideology of the Pharaohs. Open Road Media. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-5040-6059-2.

- Hartwig, Melinda K. (2014). A Companion to Ancient Egyptian Art. John Wiley & Sons. p. 424. ISBN 978-1-118-32509-4.

- For an image of a similar high-prowed boat: Porada, Edith (1993). "Why Cylinder Seals? Engraved Cylindrical Seal Stones of the Ancient Near East, Fourth to First Millennium B.C.". The Art Bulletin. 75 (4): 566, image 8. doi:10.2307/3045984. ISSN 0004-3079. JSTOR 3045984.