Nilgiri Wildlife and Environment Association

Nilgiri Wildlife and Environmental Association (NWEA) is a non-governmental organization registered in Tamil Nadu, India. Their objective is to conserve the wildlife, habitat and natural resources of the Nilgiri Hills.[1]

NWEA conducts programs on environmental education, tree planting, bird watching, animal census, soil conservation and arranges trekking parties to Mukurthi National Park.[2] NWEA has more than 500 members and is headquartered at Udagamandalam. District Collector of Nilgiris is the ex-officio president of the NWEA, and the Nilgiri North, Nilgiri South and Gudalur (DFOs) and the Field director of Mudumalai Tiger Reserve and Mukurthi National Park are its official members.

History

The NWEA was founded in 1877 as the Nilgiri Game Association by a group of British planters and big-game hunters concerned with the alarming decline in-game for hunting. It was the first wildlife conservation organisation in India.[3] As a direct result of their actions in 1879, the Nilgiris Game and Fish Preservation Act was passed by the Government of Madras.[4]

This act empowered the association to regulate hunting and fishing in the Nilgiris. Thus all game was controlled by the Association, who imposed restrictions on the types of game to be hunted and the opening and closing of seasons for shikar. They issued game licenses to the British elite to serve their recreational needs. Local tribal groups were legally excluded from their traditional use of wild animals as food, however, their snaring of small animals like monitor lizards and porcupine, fishing and scavenging the kills of predators continued.[5]

The Rules of the Nilgiri Game and Fish Preservation Association were amended in 1893, including that:

- The name of the Association shall be The Nilgiri Game and Fish Preservation Association.

- The objects of the Association are the preservation of the existing indigenous game and the introduction of game birds and animals and fish, either exotic or indigenous to India.[6]

The 1916 edition of the Nilgiri Guide and Directory published the complete details of the Institution, management, Shooting Limits, Residences, shooting Licenses, conditions, notes on rules, fishing rules, licenses, notes on rules, rewards for vermin, Hodgson's Hut, and the dak bungalows of the Nilgiri Game Association.[7]

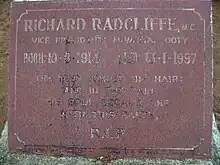

The late Major Richard Radcliff, a famous hunter turned conservationist, led the association in the creation of Mukurthi National Park. The NWEA has donated many of its former hunting bungalows to the Tamil Nadu Forest Department. NWEA is now helping the Forest Department to annex other Nilgiri Tahr habitats adjoining the park, which were excluded from the park boundaries when it was created.[8]

In 1975, with the adoption of the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 by the Tamil Nadu Government, the organization changed its objective from controlled shooting to total wildlife conservation and environmental preservation.

Rajiv Gandhi Wildlife Conservation Award for 2003 was given to the Nilgiri Wildlife and Environment Association (NWEA) in recognition of its outstanding efforts at preserving wildlife in its natural habitat and spreading ecological awareness. The award consisted of Rs. 100,000, a medallion and a citation. It was handed over by J. C. Kala, Director General of Forests, in New Delhi[3]

Activities

NWEA is an active participant in Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve Alliance, a group of conservation and people's organisations that are concerned about the future of the NBR and are working collectively towards protecting it. NWEA conducts the annual Wildlife Census at Mudumalai Tiger Reserve and the adjoining Nilgiri North Forest Division.[9]

NWEA put together a report on the effects of the controversial Satyamangalam Railway line on this ecologically sensitive area. The Central Empowered Committee (CEC) of the Supreme Court of India, after enquiry, found that the area is home to both elephants and tigers and other species listed in Schedule 1 of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972. Based on this observation the, CEC directed the Railways to withdraw the project.[10] NWEA has facilitated the rehabilitation of ex-poachers by coordinating the Periyar Foundation (an ongoing eco-development project under Project Tiger), the Literate Welfare Association, Kadamalai Gundu, Theni District and the Tamil Nadu Green Movement, Ooty, Nilgiri District. Ex-poachers and their wives have since been assisted in gaining new employment in the eco-tourism business.[11]

NWEA publicly recognizes and motivates government officials for significant contributions, dedication, involvement and personal interest in espousing the cause of environmental conservation.[12]

Publications

- Ecology And Population Dynamics of the Nilgiri Tahr in the Nilgiris, NWEA, 1992-1995

- S Joseph, AP Thomas, R Satheesh, Large Carnivores in Parambikulam Wildlife Sanctuary, Southern India, Zoos' Print Journal, Nilgiri Wildlife and Environment Association and Tamil Nadu Forest Department, 1968

- Davidar and E.R.C. The Nilgiri tahr of the Nilgiris, Tahr (Newsletter of the Nilgiri Wildlife and Environment Association), 2010–11

- Davidar, E.R.C. and H.L. Townsend, Nilgiri Wild Life Association Centenary 1877-1977, Nilgiri Wild Life Association, 1977

- Murugan, Habitat analysis of the Nilgiri Tahr in the Mukurti National Park, Nilgiri Wildlife and Environment Association, 1997

References

- Nilgiri Wildlife and Environment Association (2009). "Welcome to NWEA". Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- Veena (23 March 2008). "Mukurthi Info". Yossarian Lives. Google. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- KUMAR, DIVYA (23 October 2006). "Award for conservation". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- Davidar, E.R.C. (August 1968). The Nilgiri wild life association and status of wildlife in the Nilgiris. Journal. Vol. 65. Bombay: Bombay Natural History Society. p. 431.

- Prabhakar, R. (2005). "Resource use, culture and ecological change : a case study of the Nilglri hills of Southern India" (PDF). Phd Thesis. Bangalore, India: Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science. p. 55. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- Russell, C. E. M. (1893). "The rules of the Nilgiri game and fish preservation association, as amended at the general meeting held on 23 August 1893". Bullet and shot in Indian forest, plain and hill. With hints to beginners in Indian shooting. London: W. Thacker & co. pp. 503–504.

- EAGAN, J. S. C. (1916). "The Nilgiri Game Association". Nilgiri Guide and Directory, A handbook of general information upon the nilgiris for visitors and residents. Vepery: S.P.C.K. PRESS. pp. 145–161. Archived from the original on 17 October 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "On the Road to Paradise". Sunday Herald (Deccan Herald). 21 January 2001. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- Jayaprakash, Executive Committee Member, NWEA, C.R. (20 April 2009). "ildlife Census at Mudumalai Tiger Reserve". Welcome to the World of Media & Environment. Ooty: C.R. Jayaprakash. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "The NBR Alliance". Friends of the Niligiri Biosphere Reserve. Archived from the original on 2 December 2009. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- Jayachandran, S. (2005). "Rehabilitation of ex-poachers". Ooty: Tamil Nadu Green Movement. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- "Wildlife association plays proactive role". The Hindu. Udhagamandalam. 13 October 2009. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

External links

- Centenary Issue of the Nilgiri Wildlife Association (1977)

- The Indian Forester, Volume 31, July 1905, p. 707, Notes. The Nilgiri Game and Fish Preservation Association. discussion of hunting rules

- Campaign to remove alien plants launched – The Hindu