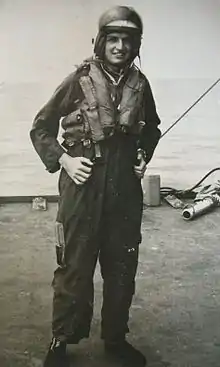

Nils Bang

Nils Daniel Bang (13 September 1941 – 2 December 1977) was a South African oceanographic scientist who was a pioneer[1] in the study of the fine structure of coastal upwelling systems.[2] In March 1969, Bang initiated, planned and executed South Africa's first truly multi-ship oceanographical research operation,[3] the Agulhas Current Project, along the current's length. Although the research was conducted on a limited budget and with rudimentary equipment,[4] Bang's studies using thousands of closely spaced bathythermograph readings were later corroborated by satellite imagery[5][6] and airborne radiation thermometry.[7]

In the field of physical oceanography, in the fine structure of coastal upwelling systems,[8] Bang—along with W.R.H (Bill) Andrews and Larry Hutchings, his counterparts in biological oceanography—produced work that was acclaimed[9] in their field. Bang's work shed light on the dynamics of the interleaving water masses of the frontal zone in coastal upwelling systems and the meandering of the front.[10]

At the time of his death, aged 36, Bang was acting head of the Physical Oceanography Division of the National Research Institute for Oceanology at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (South Africa).[11]

Scientific career

Nils Bang's oceanographic research began in 1965 when he joined the Naval Oceanographic Research unit in Youngsfield, near Cape Town. He then moved to the Oceanographic Institute at the University of Cape Town, where his key research was accomplished.[12] In June 1965, he was selected as South Africa's representative on board the US research ship, Atlantis II, the flagship of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, to take part in the multi-ship International Indian Ocean Expedition, which he accompanied on a traverse of the continental shelf from Maputo to Durban—researching the evolution and significance of submarine canyons—and then on to Australia, visiting oceanographic institutions there. After post-doctoral studies at the Geophysical Institute, University of Bergen, Norway, he joined the newly formed National Research Institute of Oceanography of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Durban, where he remained until his death.

Agulhas Current Project

Conducted along the length of the current, south of latitude 27°S, this 18-day project, from 6 to 24 March 1969, included three ships: the University of Cape Town's research vessel Thomas B. Davie, the CSIR's Meiring Naude, and the Department of Sea Fisheries' Africana II. Most of data gathered was obtained from systematically calibrated surface thermograph records from the ships:[13] Thomas B. Davie operated from west to east working the segment between Mossel Bay and the Great Fish River (as far as 500 miles south), while Meiring Naude and Africana II worked simultaneously from east to west, the former covering the Kosi Bay to East London segment and the latter the Mossel Bay to St Helena Bay segment. A CSIR aircraft—equipped with an infrared radiation thermometer for measuring ocean temperatures from a height of 1,000 feet—flew traverses across the current from Cape St Lucia to Cape Town. Some 10,000 sea water samples were taken and a similar number of temperature readings.[14] An uncharted 9,500-foot seamount found in the course of the cruise was named the Davie Seamount.

Retroflection

The findings of the Agulhas Current Project showed that a key to understanding the current's dynamics was the way it turns back on itself,[15] a phenomenon Bang described as "retroflection",[16][17][18] more commonly used to describe the way the mammalian intestine or uterus can curve back on itself. The term has since become common parlance among oceanographers.

Good Hope Jet

Following studies of the Southern Benguela system off South Africa's west coast, Bang and Andrews anticipated and subsequently discovered the strong equatorward shelf edge frontal jet off the Cape Peninsula—an intrusion of Agulhas Current water—which they named the Good Hope Jet.[19][20] The jet plays a vital role in carrying the eggs and larvae of a range fish from their food-poor[21] Agulhas Bank spawning grounds to more conducive inshore nursery areas.[22]

Biography

Early life and education

Nils Bang was born in Durban, South Africa, on 13 September 1941. His father was Daniel Nielson Bang, a Zulu linguist and son of Norwegian missionaries, and his mother was Anna Maria Bang (née Linde), the daughter of Swedish missionaries. He had a younger sister and brother, Anaida and Knut Olav. He attended Merchiston Preparatory School and later Harward, both in Pietermaritzburg. During his school years, he was a sea cadet and attended a Commonwealth sea cadet course in Britain. He studied first at the University of Natal and then at the University of Cape Town where he was awarded a PhD in 1974. (Thesis:The Southern Benguela System: Finer Oceanic Structure and Atmospheric Determinants).

Marriage and children

He married Mary Alison Coombe, a midwife, on 21 August 1965, in Pietermaritzburg. He credited his inspiration for the "retroflection" metaphor to his wife who had taught him the term during her midwifery studies. In 1967, their first daughter, Kirsten, was born in Cape Town, followed by two more daughters, Solveig in 1970 and Janice in 1973.

Death

Nils Bang died, aged 36, of colon cancer, in Durban's Entabeni Hospital on 2 December 1977.[23] At dawn on 27 January 1978, members of the CSIR staff along with his friend, retired Port Captain Jimmy Deacon, aboard the research ship Meiring Naude, committed his ashes to the sea between Umkomaas and Scottburgh on the Natal south coast.

References

- Gotthilf Hempel, Michael O’Toole and Neville Sweijd (editors)(2008). Benguela: Current of Plenty, A history of international cooperation in marine science and ecosystem management, Benguela Current Commission. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-620-42211-6

- Coastal Upwelling Ecosystems Analysis (January 1978) Vol 7

- South African Journal of Science (January 1978) Vol 74.

- Sciendaba, Vol XII No 48, 15 December 1977

- Lutjeharms, J.R.E. (1981) Features of the southern Agulhas Current circulation from satellite remote sensing. South African Journal of Science 77, 231–236

- Walker, N.D. (1986) Satellite observations of the Agulhas Current and episodic upwelling south of Africa. Deep-Sea Research 33, 1083–1106

- Schumann, E.H. (1987) The coastal ocean off the east coast of South Africa. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 46, 215–229

- Coastal Upwelling Ecosystems Analysis (January 1978) Vol 7

- Gotthilf Hempel, Michael O’Toole and Neville Sweijd (editors)(2008). Benguela: Current of Plenty, A history of international cooperation in marine science and ecosystem management, Benguela Current Commission. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-620-42211-6

- Mooers, C.N.K. (1978) Coastal Upwelling Ecosystems Analysis (CUEA) Newsletter Vol 7, No 1, January 1978

- Sciendaba (15 December 1977). Vol XII No 48

- South African Journal of Science (January 1978) Vol 74

- Bang, N.D. (1970) Dynamic Interpretations of a Detailed Surface Temperature Chart of the Agulhas Current Retroflexion and Fragmentation Area. South African Geographical Journal Volume 52, Issue 1, 1970

- The Cape Argus, 26 March 1969

- Bennett, Sara L (1988). Where Three Oceans Meet: The Agulhas Retroflection Region. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- J. R. E. Lutjeharms (2006). Three decades of research on the greater Agulhas Current. Ocean Sci. Discuss., 3, 939–995

- The Agulhas Current retroflection (2007), Related Papers, South Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (SA MOC) workshops, Physical Oceanography Division (PhOD), Atlantic Oceanographic & Meteorological Laboratory National Oceanic & Atmostpheric Administration. South Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation workshop related papers

- Bang, N. D. and F. C. Pearce (1970) Hydrological data. Agulhas Current Project, March 1969. Institute of Oceanography, University of Cape Town. Data Report No.4, 26pp.

- Bang, N. D., and W. R. H. Andrews (1974), Direct current measurements of a shelf-edge frontal jet in the southern Benguela system, Journal of Marine Research, 32, 405 – 417

- South African Journal of Science (January 1978) Vol 74

- Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem Programme (2007) The Changing State of the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem: Expert Workshop on Climate Change and Variability and Impacts Thereof in the BCLME Region. 15–16 May 2007. Workshop report compiled by Jennifer Veitch

- Shannon L.V. and M.J. O'Toole (1999) Synthesis And Assessment of Information on the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME). Thematic Report No 2. Integrated Overview of the Oceanography and Environmental Variability of the Benguela Current Region. Windhoek, Namibia

- South African Journal of Science (January 1978) Vol 74