Nine-tailed fox

The nine-tailed fox (Chinese: 九尾狐; pinyin: jiǔwěihú) is a mythical fox entity originating from Chinese mythology that is a common motif in East Asian mythology and the most famous fox spirit in Chinese culture.

| Nine-tailed fox | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

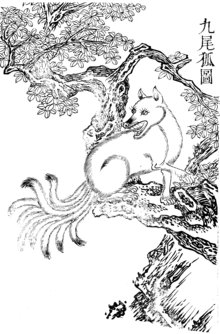

The nine-tailed fox in the Shanhaijing, depicted in an edition from the Qing dynasty | |||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 九尾狐 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | nine-tailed fox | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet |

| ||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 狐狸精 | ||||||||||

| Chữ Nôm | 𤞺𠃩𡳪 | ||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||

| Hangul | 구미호 | ||||||||||

| Hanja | 九尾狐 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||

| Kanji | 九尾の狐 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

In Chinese and East Asian folklore, foxes are depicted as spirits possessed of magic powers. These foxes are often depicted as mischievous, usually tricking other people, with the ability to disguise themselves as a beautiful woman.

The fox spirit is an especially prolific shapeshifter, known variously as the húli jīng (fox spirit) and jiǔwěihú (nine-tailed fox) in China, the kitsune (fox) in Japan, the kumiho (nine-tailed fox) in Korea, and the hồ ly tinh (fox spirit) or cáo tinh (fox spirit, a synonym of hồ ly tinh) and cửu vĩ hồ or cáo chín đuôi (nine-tailed fox) in Vietnam. Although the specifics of the tales vary, these fox spirits can usually shapeshift, often taking the form of beautiful young women who attempt to seduce men, whether for mere mischief or to consume their bodies or spirits.[1]

Origin

The earliest mention of the nine-tailed fox is the Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas), compiled from the Warring States period (475 BC–221 BC) to the Western Han (202 BC – 9 AD; 25 AD –220 AD) period. The work states:

The Land of Qing Qiu lies north of Tianwu. The foxes there have four legs and nine tails. According to another version, it is located north of Sunrise Valley.[2]

In chapter 14 of the Shanhaijing, Guo Pu had commented that the nine-tailed fox was an auspicious omen that appeared during times of peace.[2] However, in chapter 1, another aspect of the nine-tailed fox is described:

Three hundred li farther east is Qing Qiu Mountain, where much jade can be found on its south slope and green cinnabar on its north. There is a beast here whose form resembles a fox with nine tails. It makes a sound like a baby and is a man-eater. Whoever eats it will be protected against insect-poison (gu).[2]

In one ancient myth, Yu the Great encountered a white nine-tailed fox, which he interpreted as an auspicious sign that he would marry Nüjiao.[2] In Han iconography, the nine-tailed fox is sometimes depicted at Mount Kunlun and along with Xi Wangmu in her role as the goddess of immortality.[2] According to the first-century Baihutong (Debates in the White Tiger Hall), the fox's nine tails symbolize abundant progeny.[2]

Describing the transformation and other features of the fox, Guo Pu (276–324) made the following comment:

When a fox is fifty years old, it can transform itself into a woman; when a hundred years old, it becomes a beautiful female, or a spirit medium, or an adult male who has sexual intercourse with women. Such beings are able to know things at more than a thousand miles' distance; they can poison men by sorcery, or possess and bewilder them, so that they lose their memory and knowledge; and when a fox is thousand years old, it ascends to heaven and becomes a celestial fox.[3]

The Youyang Zazu made a connection between nine-tailed foxes and the divine:

Among the arts of the Way, there is a specific doctrine of the celestial fox. [The doctrine] says that the celestial fox has nine tails and a golden color. It serves in the Palace of the Sun and Moon and has its own fu (talisman) and a jiao ritual. It can transcend yin and yang.[4]

Popular fox worship during the Tang dynasty has been mentioned in a text entitled Hu Shen (Fox gods):

Since the beginning of the Tang, many commoners have worshiped fox spirits. They make offerings in their bedchambers to beg for their favor. The foxes share people's food and drink. They do not serve a single master. At the time there was a figure of speech saying, "Where there is no fox demon, no village can be established".[5]

In popular culture

Each of the nine-tailed fox appearances are listed in each section in order by year:

Games

- Ninetales in Pokémon (1996)

- Ninetails, a boss in Okami (2006)

- Ahri in League of Legends (2009)

- Kyubi in Yo-kai Watch (2013)

- Kurama in Naruto and Boruto: Naruto Next Generations (2002)

Literature, graphic novels, comics

- Kurama in Yuyu Hakusho (1990)

- Kurama The Nine Tails Fox Kiyubi Naruto (1999)

- Nine tails Guardian The God of Highschool (2011)

- The Sandman: The Dream Hunters (1999)

- Lico in The Demon Girl Next Door (2014)

- Fox Spirit Matchmaker (2015)

- The Helpful Fox Senko-san (2017)

- Shuos Jedao in Machineries of Empire (2016)

- One Hundred Ghost Tales From China and Japan by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1865)

Film

- Painted Skin (2008) and its sequel (2012)

- A Chinese Fairy Tale (2011)

- League of Gods (2016)

- Once Upon a Time (2017)

- Hanson and the Beast (2017)

- The Legend of Hei (2019)

- Jiang Ziyia (2020)

- Soul Snatcher (2020)

- Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings (2021), the Jiu Wei Hu is among the creatures residing in Ta Lo

- Umma (2022)

TV series

- The Legend of Nezha 哪吒传奇 (2003)

- Strange Tales of Liao Zhai 新聊斋志异 (2005)

- The Legend and the Hero (2007) and its sequel (2009)

- My Girlfriend Is a Gumiho (2010)

- The Investiture of the Gods (2014) and The Investiture of the Gods 2 (2015)

- Legend of Nine Tails Fox (2016)

- Fox in the Screen 屏里狐 (2016)

- Eternal Love (2017)

- Moonshine and Valentine (2017)

- Beauties in the Closet 柜中美人 (2018)

- Investiture of the Gods (2019)

- Love, Death & Robots Episode 8 (2019)

- The Life of White Fox 白狐的人生 (2019)

- Eternal Love of Dream (2020)

- Kumiho in Lovecraft Country Episode 6 "Meet Me in Daegu" (2020)

- Lee Dong Wook in Tale Of The Nine Tailed (2020)

- My Roommate Is a Gumiho (2021)

- In Kamen Rider Geats (2022), the main character's motif is based on the Nine-tailed fox. Additionally, the main character's final form takes the form of the Nine-tailed fox motif.

- In Sonic Prime (2022-present), Nine is an alternative version of Tails in another dimension. He added seven mechanic tails to his body, making him a nine-tailed fox.

- Unicorn: Warriors Eternal (2023)

- The Mickey Mouse Funhouse episode "HALT, Tiger" features the character Cho Sook (voiced by Jee Young Han), a shapeshifter residing in the Land of Myth and Legend's Shadow Mountain who can turn into a nine-tailed fox.

See also

- Huxian, Fox Immortal

- Huli jing

- Inari Ōkami, Japanese kami

- Kitsune

- Kumiho

- Hồ ly tinh

References

- Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew (2014). The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters. p. 510

- Strassberg (2002), pp. 88–89 & 184

- Kang (2006), p. 17

- Kang (2006), p. 23

- Huntington (2003), p. 14

Literature

- Huntington, Rania (2003). Alien kind: Foxes and late imperial Chinese narrative. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674010949.

- Kang, Xiaofei (2006). The cult of the fox: Power, gender, and popular religion in late imperial and modern China. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231133388.

- Strassberg, Richard E. (2002). A Chinese Bestiary: Strange Creatures from the Guideways Through Mountains and Seas. Berkeley: University of California press. ISBN 0-520-21844-2.