Nisan Bak

Nisan Bak (or Nissan Beck; Hebrew: ניסן ב"ק; 1815–1889) was a leader of the Hasidic Jewish community of the Old Yishuv in Ottoman Palestine. He was the founder of two Jewish neighborhoods in Jerusalem, Kirya Ne'emana (better known as Batei Nissan Bak) and a Yemenite Jewish neighborhood, and builder of the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue, also known as the Nisan Bak Shul.[1]

Biography

Nisan Bak was born in Berdichev as the only son of Rabbi Yisrael Bak, a Sadigura Hasid.[2][1] The family immigrated to Ottoman Syria in 1831.[1]

Father, Israel Bak

Yisrael Bak (1797–1874), also spelled Israel Bak or Back, came from a family of printers from Berdichev.[2] After working as a printer in his home town between 1815 and 1821 and having to close down his business, he eventually immigrated to Palestine in 1831.[2] He reopened his printing press in Safed,[3] being the first one to print Hebrew books there since the late 17th century.[2] In 1834, his press was destroyed and he was wounded in the peasant revolt against Egyptian rule.[2] He then settled on nearby Mount Yarmak (Meron) together with other fifteen Jewish families, where the community engaged in agriculture, making it the first Jewish farm in the country in modern times and the first new settlement of the traditional Jewish community, the Old Yishuv.[4] Affected first by the Safed earthquake of 1837 and after seeing his press and farm destroyed during the Druze revolt of 1838, he left the Galilee and relocated to Jerusalem.[2] There he established anew his printing press in 1841–the first and only Jewish printing press in the city until 1863.[2][3] Nissan helped his father run the printing press,[1] which produced a large number of books, and in 1863 Yisrael Bak also started editing Havatzelet, the second Hebrew newspaper in the country.[2] Yisrael Bak was also one of the developers of the Jewish Quarter in the Old City of Jerusalem.[3] In the early 1840s, father and son established the first Hasidic community in Jerusalem. [5] Yisrael and Nissan Bak managed to have a central Hasidic synagogue built, officially named Tiferet Yisrael after the Hebrew moniker of the head of the Ruzhin Hasidic court, Rav Yisrael Friedman of Ruzhin.[2] It was, however, better known as "Nisan Bak's synagogue".[2]

Nisan Bak: later years

After assisting his father until his death in 1874, Nisan Bak took over the printing press, which he managed for another nine years.[2] After selling it he continued with his work as a leader of the Jewish community in Jerusalem, more specifically of the Hasidic sector, where he also acted as the local head of the Ruzhin-Sadagura dynasty.[2] Bak, who had good relations with the Ottoman government, managed to soften the decrees targeting the Jewish community and initiated and carried out on its behalf the construction of several housing projects in the city.[2]

Bak was also a pioneer of the Jewish Enlightenment, or Haskalah, within his community, together with his brother-in-law I.D. Frumkin, who had renewed the publication of the Havazzelet newspaper in 1870.[2] As part of their reform attempts, Bak and Frumkin opposed the traditional distribution system of charity funds coming from abroad, the halukkah.[2] They were again active among those who established in 1884 the Ezrat Niddaḥim Society, a Jewish association designed to counter the activity of Christian missions who were trying to convert the Jews.[2] Ezrat Niddaḥim went on to build a small neighbourhood for recently arrived Yemenite Jews[2] in the Arab village of Silwan, next to Jerusalem.

Bak died in 1889 and was buried in the Mount of Olives Jewish cemetery.

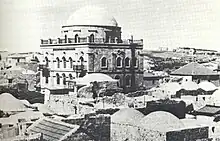

Nisan Bak Synagogue

Although there were already Hasidim in Jerusalem by 1747, they had prayed in small, private synagogues and homes. In 1839 Bak began to draw up plans for a Hasidic synagogue. Until then, in 1843, Nissan Bak travelled from Jerusalem to visit the Ruzhiner Rebbe in Sadigura. He informed him that Czar Nikolai I intended to buy a plot of land near the Western Wall with the intention of building a church and monastery. The Ruzhiner Rebbe encouraged Bak to build a synagogue there. He bought the land from its Arab owners for an exorbitant sum a few days before the Czar ordered the Russian consul in Jerusalem to make the purchase. The Czar thus bought another plot of land for a church, today the Russian Compound.[6]

The synagogue project, with Bak as architect and contractor,[7] was plagued by constant delays. Over ten years were spent raising funds and building took six years, from 1866 to 1871. The imposing, three-story synagogue was inaugurated on 19 August 1872.[8] For the next 75 years, it served as the centre for the Hasidic community in the city. It was considered one of the most beautiful synagogues of Jerusalem, with a commanding view of the Temple Mount, ornate decorations, and beautiful silver objects donated by Hasidim.[9] It was destroyed by the Arab Legion during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.[1]

Kirya Ne'emana

In 1875 Nisan Bak, together with Rabbi Shmuel Mordechai Warshavsky and under the auspices of Kollel Volhin,[10][11] founded the Jewish neighborhood of Kirya Ne'emana, initially called Oholei Moshe vi-Yhudit ("Tents of Moses and Judith"), but popularly known as Batei Nissan Bak ("Nissan Bak Houses").[1][2] The neighborhood was originally intended for Hasidic Jews, but due to lack of financing, only 30 of the planned 60 houses were constructed.[10][12] The remainder of the land was apportioned to several other groups: Syrian, Iraqi, and Persian Jews.[13] In the 1890s another neighborhood, Eshel Avraham, was erected next to Kirya Ne'emana for Georgian and Caucasian Jews.[14] These neighborhoods were virtually abandoned during the 1929 Palestine riots and the homes taken over by Christians and Muslims.[14] The remaining Jewish residents left with the Arab takeover of East Jerusalem after 1948.[15]

References

- Eisenberg 2006, p. 39.

- Kressel, Getzel (2007). Skolnik, Fred; Berenbaum, Michael (eds.). Bak, printers and pioneers in Ereẓ Israel (PDF). p. 71. ISBN 978-0-02-865931-2. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Majaro 2009, p. 14.

- ERETZ staff (22 February 2015). "From Mount Meron to the Bar Yohai Picnic Site". ERETZ magazine. Tel Aviv. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- Assaf 2010, p. 2.

- Brayer 2003, pp. 260–261.

- Brayer 2003, p. 261.

- Rossoff 2001, pp. 259–260.

- Brayer 2003, p. 263.

- Ben-Arieh 1979, p. 163.

- Tidhar 1947.

- Rossoff 2001, p. 304.

- Ben-Arieh 1979, p. 257.

- Ben-Arieh 1979, p. 165.

- Rossoff 2001, p. 306.

Bibliography

- Assaf, David (2010). "Hasidism: Historical Overview". YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- Ben-Arieh, Yehoshua (1979). עיר בראי תקופה: ירושלים החדשה בראשיתה [A City Reflected in its Times: New Jerusalem – The Beginnings] (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi Publications. p. 163.

- Brayer, Rabbi Menachem (2003). The House of Rizhin: Chassidus and the Rizhiner dynasty. Mesorah Publications. ISBN 1-57819-794-5.

- Eisenberg, Ronald L. (2006). The Streets of Jerusalem: Who, what, why. Devora Publishing. ISBN 1-932687-54-8.

- Majaro, Leon (2009). The House of Rokach. Majaro Publications. ISBN 978-0-9562859-0-4.

- Rossoff, Dovid (2001). Where Heaven Touches Earth: Jewish Life in Jerusalem from Medieval Times to the Present. Feldheim Publishers. ISBN 0873068793.

- Tidhar, David (1947). "Nisan Bak" ניסן בק. Encyclopedia of the Founders and Builders of Israel (in Hebrew). Vol. 1. Estate of David Tidhar and Touro College Libraries. p. 64.