Normal (geometry)

In geometry, a normal is an object (e.g. a line, ray, or vector) that is perpendicular to a given object. For example, the normal line to a plane curve at a given point is the (infinite) line perpendicular to the tangent line to the curve at the point. A normal vector may have length one (in which case it is a unit normal vector) or its length may represent the curvature of the object (a curvature vector). Multiplying a normal vector by -1 results in the opposite vector, which may be used for indicating sides (e.g., interior or exterior).

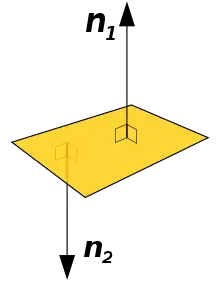

In three-dimensional space, a surface normal, or simply normal, to a surface at point P is a vector perpendicular to the tangent plane of the surface at P. The word normal is also used as an adjective: a line normal to a plane, the normal component of a force, the normal vector, etc. The concept of normality generalizes to orthogonality (right angles).

The concept has been generalized to differentiable manifolds of arbitrary dimension embedded in a Euclidean space. The normal vector space or normal space of a manifold at point is the set of vectors which are orthogonal to the tangent space at Normal vectors are of special interest in the case of smooth curves and smooth surfaces.

The normal is often used in 3D computer graphics (notice the singular, as only one normal will be defined) to determine a surface's orientation toward a light source for flat shading, or the orientation of each of the surface's corners (vertices) to mimic a curved surface with Phong shading.

The foot of a normal at a point of interest Q (analogous to the foot of a perpendicular) can be defined at the point P on the surface where the normal vector contains Q. The normal distance of a point Q to a curve or to a surface is the Euclidean distance between Q and its foot P.

Normal to surfaces in 3D space

Calculating a surface normal

For a convex polygon (such as a triangle), a surface normal can be calculated as the vector cross product of two (non-parallel) edges of the polygon.

For a plane given by the equation the vector is a normal.

For a plane whose equation is given in parametric form

where is a point on the plane and are non-parallel vectors pointing along the plane, a normal to the plane is a vector normal to both and which can be found as the cross product

If a (possibly non-flat) surface in 3D space is parameterized by a system of curvilinear coordinates with and real variables, then a normal to S is by definition a normal to a tangent plane, given by the cross product of the partial derivatives

If a surface is given implicitly as the set of points satisfying then a normal at a point on the surface is given by the gradient

since the gradient at any point is perpendicular to the level set

For a surface in given as the graph of a function an upward-pointing normal can be found either from the parametrization giving

or more simply from its implicit form giving Since a surface does not have a tangent plane at a singular point, it has no well-defined normal at that point: for example, the vertex of a cone. In general, it is possible to define a normal almost everywhere for a surface that is Lipschitz continuous.

Orientation

The normal to a (hyper)surface is usually scaled to have unit length, but it does not have a unique direction, since its opposite is also a unit normal. For a surface which is the topological boundary of a set in three dimensions, one can distinguish between two normal orientations, the inward-pointing normal and outer-pointing normal. For an oriented surface, the normal is usually determined by the right-hand rule or its analog in higher dimensions.

If the normal is constructed as the cross product of tangent vectors (as described in the text above), it is a pseudovector.

Transforming normals

When applying a transform to a surface it is often useful to derive normals for the resulting surface from the original normals.

Specifically, given a 3×3 transformation matrix we can determine the matrix that transforms a vector perpendicular to the tangent plane into a vector perpendicular to the transformed tangent plane by the following logic:

Write n′ as We must find

Choosing such that or will satisfy the above equation, giving a perpendicular to or an perpendicular to as required.

Therefore, one should use the inverse transpose of the linear transformation when transforming surface normals. The inverse transpose is equal to the original matrix if the matrix is orthonormal, that is, purely rotational with no scaling or shearing.

Hypersurfaces in n-dimensional space

For an -dimensional hyperplane in -dimensional space given by its parametric representation

where is a point on the hyperplane and for are linearly independent vectors pointing along the hyperplane, a normal to the hyperplane is any vector in the null space of the matrix meaning That is, any vector orthogonal to all in-plane vectors is by definition a surface normal. Alternatively, if the hyperplane is defined as the solution set of a single linear equation then the vector is a normal.

The definition of a normal to a surface in three-dimensional space can be extended to -dimensional hypersurfaces in A hypersurface may be locally defined implicitly as the set of points satisfying an equation where is a given scalar function. If is continuously differentiable then the hypersurface is a differentiable manifold in the neighbourhood of the points where the gradient is not zero. At these points a normal vector is given by the gradient:

The normal line is the one-dimensional subspace with basis

Varieties defined by implicit equations in n-dimensional space

A differential variety defined by implicit equations in the -dimensional space is the set of the common zeros of a finite set of differentiable functions in variables

The Jacobian matrix of the variety is the matrix whose -th row is the gradient of By the implicit function theorem, the variety is a manifold in the neighborhood of a point where the Jacobian matrix has rank At such a point the normal vector space is the vector space generated by the values at of the gradient vectors of the

In other words, a variety is defined as the intersection of hypersurfaces, and the normal vector space at a point is the vector space generated by the normal vectors of the hypersurfaces at the point.

The normal (affine) space at a point of the variety is the affine subspace passing through and generated by the normal vector space at

These definitions may be extended verbatim to the points where the variety is not a manifold.

Example

Let V be the variety defined in the 3-dimensional space by the equations

This variety is the union of the -axis and the -axis.

At a point where the rows of the Jacobian matrix are and Thus the normal affine space is the plane of equation Similarly, if the normal plane at is the plane of equation

At the point the rows of the Jacobian matrix are and Thus the normal vector space and the normal affine space have dimension 1 and the normal affine space is the -axis.

Uses

- Surface normals are useful in defining surface integrals of vector fields.

- Surface normals are commonly used in 3D computer graphics for lighting calculations (see Lambert's cosine law), often adjusted by normal mapping.

- Render layers containing surface normal information may be used in digital compositing to change the apparent lighting of rendered elements.

- In computer vision, the shapes of 3D objects are estimated from surface normals using photometric stereo.[1]

- The normal vector may be obtained as the gradient of the signed distance function

Normal in geometric optics

The normal ray is the outward-pointing ray perpendicular to the surface of an optical medium at a given point.[2] In reflection of light, the angle of incidence and the angle of reflection are respectively the angle between the normal and the incident ray (on the plane of incidence) and the angle between the normal and the reflected ray.

See also

- Dual space – In mathematics, vector space of linear forms

- Ellipsoid normal vector

- Normal bundle – term related to the preceding concept

- Pseudovector – Physical quantity that changes sign with improper rotation

- Tangential and normal components

- Vertex normal – directional vector associated with a vertex, intended as a replacement to the true geometric normal of the surface

References

- Ying Wu. "Radiometry, BRDF and Photometric Stereo" (PDF). Northwestern University.

- "The Law of Reflection". The Physics Classroom Tutorial. Archived from the original on April 27, 2009. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Normal Vector". MathWorld.

- An explanation of normal vectors from Microsoft's MSDN

- Clear pseudocode for calculating a surface normal from either a triangle or polygon.