North Carolina Commissioner of Labor

The Commissioner of Labor is a statewide elected office in the U.S. state of North Carolina. The commissioner is a constitutional officer who leads the state's Department of Labor. North Carolina's general statues provide the commissioner with wide-ranging regulatory and enforcement powers to tend to the welfare of the state's workforce. They also sit on the North Carolina Council of State. The incumbent is Josh Dobson, who has served since January 2021.

| Commissioner of Labor of North Carolina | |

|---|---|

Logo of the North Carolina Department of Labor | |

| Member of | Council of State |

| Seat | Raleigh, North Carolina |

| Term length | Four years, no term limit |

| Formation | 1887 |

| Salary | $146,421 |

| Website | www |

The original Bureau of Labor Statistics, the historical precursor of the present Department of Labor, was created by the North Carolina General Assembly in 1887, with provision for appointment by the governor of a Commissioner of Labor Statistics for a two-year term. In 1899 another act was passed providing that the commissioner, beginning with the general election of 1900, be elected by the people for a four-year term. The office was elevated to constitutional status in 1944.

History of the office

Following lobbying by the Knights of Labor,[1] the Bureau of Labor Statistics was established by the North Carolina General Assembly in 1887 as a sub-agency of the Department of Agriculture, Immigration, and Statistics.[2] The bureau was led by a commissioner, who was to be appointed by the Governor of North Carolina with the consent of the North Carolina Senate. With the aid of a chief clerk and other appointed assistants, the commissioner of labor statistics gathered information on workers' hours, wages, education, and finances.[2][3] They were also tasked with promoting the "mental, material, social, and moral prosperity" of the workforce. Their findings were compiled into an annual report to be submitted to the General Assembly and the press.[2] The first appointed commissioner was Wesley N. Jones.[4][5] In 1899 the General Assembly transformed the Bureau of Labor Statistics into an independent agency responsible for both statistic collection and printing of state documents, the Bureau of Labor and Printing.[2] At the same time, they made the commissioner a popularly-elected official with four-year terms, beginning with the elections of 1900 with an interim commissioner to be appointed by the legislators.[5] Henry B. Varner was the first popularly-elected commissioner.[6] An assistant commissioner's position was also created to be filled by a person with printing experience.[2]

Early on, the commissioner's bureau had minimal staffing and responsibilities.[7] In 1919 the bureau was elevated to department status, and in 1931 the General Assembly reorganized it and shortened its name to Department of Labor,[2] opening it up to more regulatory and enforcement responsibilities.[7] The commissionership was made a constitutional office in 1944.[8] A 1968 constitutional study commission recommended making the governor responsible for the selection of the commissioner to reduce voters' burden by shortening the ballot, but this proposal was disregarded by the General Assembly when it revised the state constitution in 1971.[9]

Historically, the office has not usually been politically powerful or prominent in the state.[10][11] Cherie Berry, who assumed the commissionership in 2001, was the first woman elected to the office.[12] In 2005, Berry began placing her photo on labor department inspection certification forms in elevators in North Carolina.[13] The move garnered increased public attention to herself and the commissioner's office, and earned her the moniker "elevator queen".[14][15] Berry holds the record for longest tenure as labor commissioner.[16] The incumbent commissioner, Josh Dobson, assumed office on January 2, 2021.[17] Dobson continued the practice of putting the commissioner's photo on elevator inspection certifications.[18]

Powers, duties, and structure

.jpg.webp)

Article III, Section 7, of the Constitution of North Carolina stipulates the popular election of the commissioner of labor every four years. The office holder is not subject to term limits. In the event of a vacancy in the office, the Governor of North Carolina has the authority to appoint a successor until a candidate is elected at the next general election for members of the General Assembly. Per Article III, Section 8 of the constitution, the commissioner sits on the Council of State.[19] They are ninth in line of succession to the governor.[20][21]

The North Carolina Department of Labor is by law tasked with ensuring the "health, safety, and general well-being" of the state's workforce.[22] North Carolina's general statutes grant the commissioner of labor wide-ranging regulatory and enforcement powers.[23] The commissioner leads the Department of Labor and its constituent bureaus.[24] As of February 2023, the department has 318 employees retained under the terms of the State Human Resources Act.[25] The commissioner is advised by five statutory boards in creating policies and developing programs.[2] As with all Council of State officers, the commissioner's salary is fixed by the General Assembly and cannot be reduced during their term of office.[26] In 2022, the commissioner's annual salary was $146,421.[27] The commissioner's office is located in the Labor Building, formerly the meeting place of the North Carolina Supreme Court, on West Edenton Street in Raleigh, North Carolina.[17]

List of Commissioners of Labor

Appointed commissioners

| No. | Commissioner | Term in office | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Wesley N. Jones | 1887 – 1889 | [5] |

| 2 |  |

John C. Scarborough | 1889 – 1892 | [5] |

| 3 | William I. Harris | 1892 – 1893 | [5] | |

| 4 |  |

Benjamin R. Lacy | 1893 – 1897 | [5] |

| 5 |  |

James Y. Hamrick | 1897 – 1899 | [5] |

| 6 |  |

Benjamin R. Lacy | 1899 – 1901 | [5] |

Elected commissioners

| No. | Commissioner | Term in office | Party | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Henry B. Varner | 1901 – 1909 | Democratic | [5] |

| 2 |  |

Mitchell L. Shipman | 1909 – 1925 | Democratic | [5] |

| 3 |  |

Franklin D. Grist | 1925 – 1933 | Democratic | [5] |

| 4 |  |

Arthur L. Fletcher | 1933 – 1938 | Democratic | [5] |

| 5 |  |

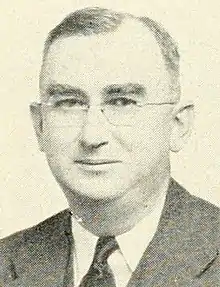

Forrest H. Shuford | 1938 – 1954 | Democratic | [5] |

| 6 |  |

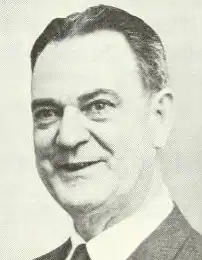

Frank Crane | 1954 – 1973 | Democratic | [5] |

| 7 |  |

William C. Creel | 1973 – 1975 | Democratic | [5] |

| 8 |  |

Thomas Avery Nye Jr. | 1975 – 1977 | Republican | [5] |

| 9 | John C. Brooks | 1977 – 1993 | Democratic | [5] | |

| 10 |  |

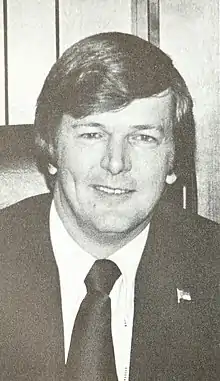

Harry Payne | 1993 – 2000 | Democratic | [5] |

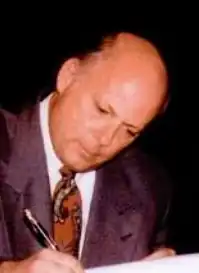

| 11 | .jpg.webp) |

Cherie Berry | 2001 – 2021 | Republican | [28] |

| 12 |  |

Josh Dobson | 2021 – present | Republican | [17] |

References

- "Gov. Scales And the Knights of Labor". Greensboro North State. March 10, 1887. p. 4.

- Williams, Wiley J. (2006). "Labor, North Carolina Department of". NCPedia. North Carolina Government & Heritage Library. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- Jones, W. N. (March 30, 1887). "The Bureau of Labor Statistics". The Progressive Farmer. p. 3.

- Scott, W. W. Jr., ed. (March 9, 1887). "The General Assembly". The Lenoir Topic. p. 2.

- North Carolina Manual 2011, p. 206.

- North Carolina Manual 2011, pp. 206–207.

- North Carolina Manual 2001, p. 271.

- Orth & Newby 2013, p. 123.

- Guillory 1988, p. 41.

- Smith & Weinberg 2016, p. 502.

- Simon 2020, pp. 178–179.

- North Carolina Manual 2011, p. 207.

- Smith & Weinberg 2016, p. 497.

- Smith & Weinberg 2016, p. 499.

- "Cherie Berry, The 'Elevator Lady,' Won't Seek Reelection". WUNC 91.5. WUNC North Carolina Public Radio. Associated Press. April 2, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- Quesenberry, Dolores (November 2020). "From Linthead to Queen" (PDF). Labor Ledger. North Carolina Department of Labor. pp. 1, 3–4.

- "Historical Note About the Labor Building". North Carolina Department of Labor. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- Spivey, Stacey (November 11, 2021). "A new elevator 'king' takes the throne in NC". WFMY News2. WFMY-TV. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- North Carolina Manual 2011, p. 138.

- "States' Lines of Succession of Gubernatorial Powers" (PDF). National Emergency Management Association. May 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- Orth & Newby 2013, p. 115.

- Havlak, Julie (October 11, 2022). "Labor commissioner hopefuls debate in Raleigh". The McDowell News. p. B5.

- North Carolina Manual 2011, p. 203.

- Selley, Audrey (October 1, 2020). "What you need to know about the NC commissioner of labor candidates". The Chronicle. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- "Current State Employee Statistics". North Carolina Office of State Human Resources. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- Orth & Newby 2013, p. 125.

- "What raises are NC teachers, state employees getting in 2022". The News & Observer. July 20, 2022. Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- "'Death don't stop nothing': The dangerous shifts of North Carolina factory workers". The Fayetteville Observer. October 28, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

Works cited

- Guillory, Ferrel (June 1988). "The Council of State and North Carolina's Long Ballot : A Tradition Hard to Change" (PDF). N.C. Insight. N.C. Center for Public Policy Research. pp. 40–44.

- North Carolina Manual. Raleigh: North Carolina Secretary of State. 2001. OCLC 436873840.

- North Carolina Manual (PDF). Raleigh: North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State. 2011. OCLC 2623953.

- Orth, John V.; Newby, Paul M. (2013). The North Carolina State Constitution (second ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199300655.

- Simon, Bryant (2020). The Hamlet Fire: A Tragic Story of Cheap Food, Cheap Government, and Cheap Lives. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781469661377.

- Smith, Jacob F. H.; Weinberg, Neil (2016). "The Elevator Effect: Advertising, Priming, and the Rise of Cherie Berry". American Politics Research. 44 (3): 496–522. doi:10.1177/1532673X15602755. S2CID 156042718.