North Potomac, Maryland

North Potomac is a census-designated place and unincorporated area in Montgomery County, Maryland, United States. It is located less than 5 miles (8.0 km) north of the Potomac River, and is about 20 miles (32 km) from Washington, D.C. It has a population of 23,790 as of 2020.[2]

North Potomac, Maryland | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Coordinates: 39°5′44″N 77°14′14″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | |

| County | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 6.56 sq mi (16.99 km2) |

| • Land | 6.52 sq mi (16.89 km2) |

| • Water | 0.04 sq mi (0.10 km2) |

| Elevation | 390 ft (120 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 23,790 |

| • Density | 3,648.21/sq mi (1,408.48/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 20878, 20850 |

| Area code(s) | 301 and 240 |

| FIPS code | 24-56875 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2389581 |

The region's land was originally used for growing tobacco, which was replaced by wheat and dairy farming after the soil became depleted. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was used by local farmers to ship their grain (or flour made from the grain at the local mills), and two former canal locks are located less than 5 miles (8.0 km) away in the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park. In addition, infrastructure remains for what was one of the state's leading dairy farms during the first half of the 20th century.

North Potomac did not get an identity of its own until 1989, when the United States Post Office allowed the use of the North Potomac name for what is mostly a collection of housing sub-divisions, farms, and wooded parks. The United States Census Bureau listed a North Potomac in 1970 but not 1980. In 2000, it began recognizing North Potomac as a census designated place. Today, the community benefits from its proximity to workplaces such as the Shady Grove Hospital area and the I-270 Technology Corridor. Washington, D.C. is accessible by automobile or public transportation. The median household income is nearly $160,000, and nearly half of the eligible residents have a graduate or professional degree.

History

Captain John Smith explored the Potomac River in 1608 and mapped the area, including land that would become Montgomery County.[3] The first settlements were established in 1688, and were near Rock Creek and what became Rockville. The next stage of settlements was further west along the Potomac near Darnestown and Poolesville.[4] The land had been occupied by Native Americans of the Piscataway Confederation.[3] Modern-day Darnestown Road, which forms the northern border of North Potomac, was a trail of the indigenous Seneca people and is one of the oldest roads in Montgomery County.[5]

Originally, the land around present-day North Potomac was used by European settlers for growing tobacco and corn. During the 19th century, a network of roads, mills, and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (a.k.a. C&O Canal) provided farmers with better access to markets. Dufief Mill Road, which runs through the center of North Potomac, leads to the DuFief Mill (established 1850)—one of the mills that were used by farmers in this part of Montgomery County.[6] By 1840, much of the county's soil was depleted. Quakers began introducing improved farming practices and agriculture was revitalized. By 1860, farmers were growing corn, wheat and oats.[7]

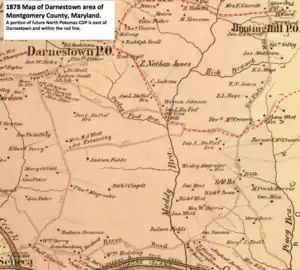

In 1878, today's North Potomac was still farmland. The nearest general stores and post offices were in Hunting Hill, Travilah, and Darnestown. The Hunting Hill Post Office and general store was located on Darnestown Road between Muddy Branch Road and Travilah Road, and it also provided wheelwright and blacksmith services.[8] It operated from 1873 until 1929.[8] Darnestown had three country stores, and the Windsor store also served as a Post Office until 1911.[9] Travilah, located closer to the canal, had a general store but no name in 1878. The Travilah Post Office was established in 1883, and the community eventually took that name.[10] Eventually, some of the farmland was sold.[11] During the Great Depression, some farmers became eager to sell their land because of financial hardship. Wealthy individuals began buying property in the Potomac area as part of their search for land where they could ride horses and hunt.[12] Some of this equestrian heritage continues in North Potomac today at the Potomac Horse Center. Mortgage banker Frederick Harting established this training facility, for horses and riders, in the early 1960s. It was purchased by Montgomery County in 1981 and has been the site of horse shows.[13]

Several area farms, such as the 355-acre (144 ha) Maple Spring Farm, continued well into the 20th century.[14] Much of this farm's land was sold in the 1970s and became North Potomac's Dufief subdivision.[15] In 1970, the United States Census Bureau considered North Potomac an unincorporated place that was part of the Darnestown and Travilah areas.[16][17] By 1989, North Potomac consisted of about 25 housing subdivisions mixed with old farms. About 80 percent of those subdivisions were built since 1983.[11] In late 1989, the United States Postal Service approved the North Potomac name for a region surrounded by the Montgomery County communities of Darnestown, Travilah, Gaithersburg and Rockville. ZIP Codes were not changed, so most of North Potomac uses the 20878 code used by Gaithersburg and part of Darnestown.[11] For 1990, North Potomac began being listed by the Census Bureau as a census-designated place, but census records show no data for 1980.[18] The last major farm in the area is the Hanson Farm, and work began in 2009 for approval to build single-family homes on the farmland.[12][19]

Historic places

The historic DuFief Mill site is located near the intersection of Turkey Foot Road and the Muddy Branch in Muddy Branch Regional Park.[6] John L. DuFief built a mill complex in the 1850s that was about three miles (4.8 km) from the C&O Canal.[20] A road connected his gristmill, blacksmith's shop, and miller's house to the Pennyfield Lock on the C&O Canal, where he operated a warehouse, barrel house, and wharf. The canal was necessary because the Potomac River was not navigable by ships and barges at Great Falls.[21] Construction of the C&O Canal, which began in the 1830s and was completed in 1850, opened the region to important markets and lowered shipping costs.[22] After DuFief established this mill and its access to the canal, more roads were constructed, which enabled him to serve farmers from as far away as Germantown and Damascus in addition to the local growers.[6]

Three other sites of historic significance remain in North Potomac. The privately owned Maple Spring Barns are located at the intersection of Dufief Mill Road and Darnestown Road, and were part of one of the largest dairy farms in Maryland during the 20th century.[23] The Pleasant View Historic Site consists of the Pleasant View Methodist Episcopal Church (chapel built in 1914), Pleasant View Cemetery, and the Quince Orchard Colored School (built in 1901).[24] All structures are located on the south side of Darnestown Road near the Quince Orchard area. The church's congregation was established around 1868.[25] The Poplar Grove Baptist Church, located on Jones Lane, is the sole surviving 19th century Baptist church of an African-American congregation in Montgomery County.[26] The church was built in 1893 near a tributary of the Muddy Branch, and immersion baptisms are said to have taken place in the tributary during the church's early years.[26]

Geography

As an unincorporated area, North Potomac's boundaries are not officially defined. However, the United States Census Bureau recognized a North Potomac in the 1970 census, and then as a census-designated place (North Potomac CDP) in every census since 1990.[27] As of the 2010 census, North Potomac is located north of the Potomac River in west central Montgomery County, roughly 20 miles (32 km) from Washington, D.C.[28][29] It is bordered to the north by Gaithersburg, which lies beyond Maryland Route 28 (Darnstown Road). Rockville, along Glen Road, is on the east border, while the Travilah CDP, mostly along Travilah Road, forms the southern border. The Darnestown CDP along Jones Lane and Turkey Foot Road forms the western boundary.[30][28] Like North Bethesda, residents have held misconceptions about North Potomac's existence, incorrectly arguing that it is part of Gaithersburg and that the name is a neologism created by realtors.[31]

Between the 1990 and 2000 census, North Potomac gained and lost land. The loss was caused when a portion of the North Potomac territory, plus Potomac territory, was used to create the Travilah census designated place.[27] According to the United States Census Bureau, North Potomac has a total area of 6.6 square miles (17 km2), virtually all land.[28] The Muddy Branch and its tributary Rich Branch are streams that run through North Potomac, and the Muddy Branch empties into the Potomac River.[32] The United States Geological Survey lists two features in Montgomery County with North Potomac in all or part of their name. The North Potomac Census Designated Place is listed with an elevation of 390 feet (120 m), while the North Potomac Populated Place has an elevation of 256 feet (78 m).[33][34][Note 1]

Climate

According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, North Potomac has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[35] There are four distinct seasons, with winters typically cold with moderate snowfall, while summers are usually warm and humid. July is the warmest month, while January is the coldest. Average monthly precipitation ranges from about 2.5 to 4 inches (6.4 to 10.2 centimetres). The highest recorded temperature was 105.0 °F (40.6 °C) and the lowest recorded temperature was −13.0 °F (−25.0 °C).[36] There is a 50 percent probability that the first frost of the season will occur by October 21, and a 50 percent probability that the final frost will occur by April 16.[37]

| Climate data for Gaithersburg, MD (same zip code as North Potomac) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 40 (4) |

44 (7) |

53 (12) |

65 (18) |

73 (23) |

81 (27) |

85 (29) |

83 (28) |

76 (24) |

65 (18) |

55 (13) |

44 (7) |

64 (18) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 27 (−3) |

29 (−2) |

36 (2) |

46 (8) |

55 (13) |

64 (18) |

69 (21) |

67 (19) |

60 (16) |

48 (9) |

39 (4) |

31 (−1) |

48 (9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.88 (73) |

2.81 (71) |

3.61 (92) |

3.22 (82) |

4.13 (105) |

3.49 (89) |

3.67 (93) |

2.90 (74) |

3.83 (97) |

3.29 (84) |

3.53 (90) |

3.00 (76) |

40.36 (1,026) |

| Source: Weather Channel[36] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 12,546 | — | |

| 1990 | 18,456 | — | |

| 2000 | 23,044 | 24.9% | |

| 2010 | 24,410 | 5.9% | |

| 2020 | 23,790 | −2.5% | |

| source:[38][39] 2010–2020[2] | |||

As of 2018 estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau, North Potomac has a population of 24,148 with a median household income of $159,232 and a poverty rate of 2.3 percent.[40] The number of housing units in North Potomac is estimated to be 8,168.[41] The median age is 43.4 years, which is higher than the 37.9 median for the United States.[40] 25.5 percent of residents were under the age of 18, while 14.2 percent were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.1 percent male and 51.9 percent female.[41]

The racial makeup of North Potomac was 51.6 percent White alone, 35.8 percent Asian alone, 7.3 percent Black or African American alone, and a 5 percent total for all other categories. Over half of the Asian population is Chinese, while Asian Indians and Koreans also have a significant presence.[41] The educational attainment for the community is above the average for the United States, with 97.8 percent of North Potomac residents eligible being a high school graduate or higher, while the same figure for the United States is 87.7 percent. A graduate or professional degree was attained by 47.6 percent.[40]

In 2017, ranking and review site Niche ranked North Potomac as the best place to live in Maryland and 43rd in the nation out of more than 15,000 places.[42] In 2019, Money Inc. named North Potomac the best place to live in Maryland because of great schools, low crime, and a booming job market.[43]

2010 census

North Potomac is considered part of the Washington, DC–VA–MD Urbanized Area.[44] As of the 2010 U.S. census, its population was 24,410—a ranking of 51 for the state of Maryland.[45] The population density was 3,743.9 inhabitants per square mile (1,445.5/km2). There were 8,178 housing units at an average density of 1,254.3 per square mile (484.3/km2).[46] The racial makeup of the community was 51.9% White, 7.3% African American, 0.2% Native American, 35.8% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, and 3.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race was 5.7% of the population.[47]

Government

The western side of North Potomac is in District 2 of the Montgomery County Council, while the eastern side is in District 3.[48] The county council has representatives from each of five districts plus four at-large members. All members are elected at once and serve four-year terms.[49] The North Potomac Citizen's Association is a volunteer organization that keeps state and local governments informed on North Potomac's point of view for issues that affect the community.[50]

North Potomac is served by the Montgomery County Police Department, which has its 1st District–Rockville headquarters on the north side of Darnestown Road in Gaithersburg.[51] Portions of the North Potomac CDP may also be served by the Rockville City Police Department.[52] The Montgomery County Fire & Rescue Service Public Safety Headquarters is at the same location as the 1st District police headquarters.[53] Two fire and rescue stations that serve North Potomac are located on Darnestown Road. Station 32 is located at the intersection of Darnestown Road and Shady Grove Road.[53] Station 31 is located further west near Quince Orchard, and is a Rockville Fire Department that provides services for the county.[54]

Economy

The data based on the Census Bureau 2012 Survey of Business Owners lists 2,292 firms in North Potomac.[40] The number of firms with paid employees is 362, and those firms employ 1,579 people. The data are divided using the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), and the Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services category (NAICS 54) is the leader in firms (168), paid employees (312), annual payroll $16.2 million, and sales $50.4 million.[55] Other important categories include Health Care and Social Assistance (NAICS 62) and Administrative and Support (NAICS 56).[55]

North Potomac is close to major employers such as Shady Grove Hospital and the technology companies along Interstate 270.[32] Over 25 biotech companies and over 25 technology companies have facilities in the I-270 Technology Corridor in the Rockville, Gaithersburg, or Germantown area.[56] North Potomac residents who commute further distances to work typically use Interstate 270 or the Shady Grove subway station on the Washington Metro system, which serves the region.[32]

North Potomac residents have two shopping centers located within its 2010 census CDP boundaries and several others in the nearby area. The Travilah Square Shopping Center is located at the intersection of Travilah Road and Darnestown Road. It has a grocery store, pizza place, and other stores.[57] The Traville Village Center is located on Traville Gateway Drive near Shady Grove Road and the Universities at Shady Grove. It has space for 25 merchants, and has a grocery store and multiple restaurants.[58] Based on 2012 census data, total retail sales for the North Potomac CDP were $39.0 million.[59]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Maryland Route 28, a state highway, connects North Potomac with Rockville and provides access to Interstate 270.[28] Darnestown Road and Route 28 are united along most of North Potomac's northern border.[28] Dufief Mill Road and Quince Orchard Road run through the middle of the community and connect with Darnstown Road.[28] The closest interstate highways are to the north and east. Maryland's Interstate 270 is a major north–south highway that connects with Washington's Capital Beltway (a.k.a. Interstate 495).[60] Interstate 370 and the Intercounty Connector toll road (MD 200) are nearby major east–west highways that connect to Interstate 95.[61]

Portions of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority's Metrorail system are located in Montgomery County, and Red Line stations on the west side of the county are closest to North Potomac.[62] Among those west side Metro stations are Shady Grove (Gaithersburg), Rockville, and Twinbrook (south Rockville).[63] At least four Montgomery County Ride-On bus routes run through North Potomac and connect riders with the Traville Transit Center and Universities at Shady Grove, Shady Grove and Rockville Metro stations, Shady Grove Hospital, and Quince Orchard Library via routes on Travilah Road, Dufief Mill Road, and Darnestown Road.[64]

Utilities

North Potomac's electric power is provided by Pepco (Potomac Electric Power Company), which serves much of Montgomery County, portions of Prince George's County, and all of the District of Columbia.[65] Washington Gas provides natural gas service to residents and businesses.[66] The Montgomery County Department of Environmental Protection provides for curbside garbage, recycling, and yard waste collection and disposal.[67] The Shady Grove Processing Facility and Transfer Station, a county waste collection facility located in Rockville, is available for drop off of garbage, recycling, and yard debris.[68] The Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission (WSSC) provides water and wastewater treatment for North Potomac.[69] Drinking water comes from the WSSC treatment facility on the Potomac River, while sewage is treated at a plant in the District of Columbia.[70]

Healthcare

The nearest general hospital is the Adventist HealthCare Shady Grove Medical Center in Rockville.[71] This medical facility has a five-star rating from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.[72]

Education

North Potomac is served by Montgomery County Public Schools. Public high school students in North Potomac attend either Thomas S. Wootton or Quince Orchard high schools.[73] Quince Orchard High School is located at the intersection of Quince Orchard Road and Darnestown Road, placing it on the northwest side of the North Potomac CDP.[74][Note 2] Wootton High School is located in Rockville, on the east side of the North Potomac CDP.[75] Area residents have cited the Wootton school cluster as a factor in their home buying decision.[32] In 2019, U.S. News & World Report ranked Wootton High School 2nd highest in Maryland and 125th in the nation.[76] Each of the two high schools has two feeder middle schools. Multiple elementary schools contribute to the middle schools, and several are located within the North Potomac CDP.[73]

Higher education

The Universities at Shady Grove is located within North Potomac and offers select degree programs from nine public Maryland universities.[77] Instead of being a university itself, this campus partners with other universities and offers courses for 80 upper-level undergraduate, graduate degree, and certificate programs. The participating universities handle admissions.[78] Johns Hopkins University has a campus in Rockville near the Universities at Shady Grove.[79] Montgomery College has a campus close to North Potomac in Rockville and a training center in Gaithersburg. Three Montgomery College campuses and online classes serve about 54,000 students offering associate degrees and courses that will transfer to other institutions.[80]

Public library

Several libraries are located in North Potomac or only a few miles away. Quince Orchard library is part of the Montgomery County Public Library system and is located across the street from Quince Orchard High School in North Potomac.[81] Priddy Library is part of the University of Maryland Libraries system and is located at the Universities at Shady Grove in North Potomac.[82] Rockville Memorial Library, also part of the county library system, is located in Rockville three blocks from the Rockville Metro station.[83] While the Rockville Memorial Library celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2001; Quince Orchard Library was only a year old at that time.[84] The Priddy Library opened in 2007.[85]

Culture

Arts

North Potomac does not have art centers of its own, but some museums can be found in adjacent communities.[86] The Beall–Dawson House, built circa 1815, contains exhibits on life in 19th century Rockville.[87] The Gaithersburg Community Museum is located in an old Baltimore and Ohio Railroad complex in Olde Town Gaithersburg, and focuses on educating children about Gaithersburg history.[88] Glenstone Modern Art Museum is south of North Potomac near the intersection of Travilah Road and Glen Road.[89] The Strathmore Music and Arts Center in North Bethesda has a concert hall and art exhibits.[90]

Parks and recreation

Nancy H. Dacek North Potomac Recreation Center is located on Travilah Road adjacent to the county's Big Pines Local Park. The center has a gym, basketball court, and other recreation facilities.[91] The Potomac Horse Center, at the intersection of Dufief Mill Road and Quince Orchard Road, offers equestrian training and holds horse shows.[92] The Westleigh Recreation Club, located on Dufief Mill Road, is a private pool and tennis club.[93]

The Montgomery County Park System has over 200 miles (320 km) of hiking trails.[94] Among those trails is the Muddy Branch Greenway Trail, which passes North Potomac's Potomac Horse Center on a 9-mile (14 km) route between Darnestown Road and Blockhouse Point Conservation Park.[95] Construction of the Powerline Trail (a.k.a. Pepco Trail) began in 2018, and this trail will connect North Potomac (Muddy Branch Stream Valley Park) with the South Germantown Recreation Park, which is the home of the Maryland SoccerPlex.[96][97]

Four of North Potomac's five county parks range in size from 10 to 15 acres (4 to 6 ha).[Note 3] These parks typically have sports facilities, a playground, and a picnic area.[98] A fifth park, Muddy Branch Stream Valley Park, is 876 acres (355 ha) and contains the Muddy Branch Greenway Trail.[99]

In addition to parks and trails maintained by the county, many housing divisions have locally maintained playgrounds, parks, and short hiking trails. Examples are the Dufief Hiking Trail in the Dufief neighborhood and the unnamed paths and playgrounds in Potomac Crossing.[100][101] Some housing divisions have their own pool in addition to other recreation facilities.[102][103]

The Pennyfield Lock House (Lock #22) is located near North Potomac along the C&O Canal and is part of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park.[104] The 630-acre (250 ha) Blockhouse Point Conservation Park is also located along the Potomac River and C&O Canal.[105][106] The Maryland SoccerPlex is located less than 10 miles (16 km) away and has indoor and outdoor facilities for soccer and other activities.[107]

Notes

Footnotes

- The North Potomac CDP has a latitude of 390544N and a longitude of 0771414W, while the North Potomac Populated Place has a latitude of 390458N and a longitude of 0771554W.[33][34] The Geographic Names Information System uses an ANSI Code for North Potomac of 02389581 and a Place Identifier of 2456875. North Potomac has a GIS ID of 296 and a FID of 295. The State FIPS code is 24 and the Place FIPS is 56875.[30]

- Since the U.S. Postal Service and the Census Bureau do not have the same definition for North Potomac, one may see Gaithersburg and Rockville addresses for places in the North Potomac CDP.[11]

- The four parks are Aberdeen, Big Pines, Dufief, and Quince Orchard Knolls.

Citations

- "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- "QuickFacts: North Potomac CDP, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- Montgomery County Historical Society 1999, p. 3

- Boyd 1879, p. 43

- Curtis 2020, p. 76

- Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 12

- Montgomery County Historical Society 1999, pp. 6–7

- Curtis 2020, p. 84

- Curtis 2020, p. 77

- Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 226

- Pressley, Sue Anne (August 3, 1989). "No Man's Land Reborn as North Potomac". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- Drydan, Steve (September 27, 2010). "The History of Potomac". Bethesda Magazine – Bethesda Beat. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- Yang, Zhuang (June 29, 1983). "F.G. Harting Jr. Dies". Washington Post. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 234

- "Garrett Farm M: 25-1" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Maryland government. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- U.S. Census Bureau 1973, p. 18

- "North Potomac – Potomac Subregion Master Plan, April 2002" (PDF). Montgomery County, MD – Montgomery Planning. Montgomery County Planning Department. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- U.S. Census Bureau 2003, p. 21

- "Before the County Council for Montgomery County, Maryland..." (PDF). Montgomery County, MD – Office of Zoning and Administrative Hearings. Montgomery County government. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- Maryland Department of Transportation (2020). Maryland (PDF) (Map). Baltimore, Maryland: Maryland Department of Transportation State Highway Administration. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Chesapeake & Ohio Canal". Visit Maryland, Maryland Office of Tourism Development. Maryland Department of Commerce. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "Canal History: Canal Era from the 1830s–1870s". C&O Canal Trust. C&O Canal Trust. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Historic Preservation Commission Staff Report – Maple Spring Barns" (PDF). Montgomery County Planning. Montgomery County government. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- "Preservation Maryland – Pleasant View: From Civil War to Civil Rights". Preservation Maryland. Preservation Maryland. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, pp. 227–228

- Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 224

- U.S. Census Bureau 2003, p. III-7

- "North Potomac, CDP, Maryland – Place Selection Map". United States Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- "Montgomery County, MD: Close to the Action". Visit Montgomery. Conference and Visitors Bureau of Montgomery County, MD, Inc. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Maryland Census Designated Areas – Census Designated Places 2010 (Data Tab with North Potomac, MD, USA search)". Maryland.gov. Maryland government. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- "North Bethesda and North Potomac "You mean Rockville and Gaithersburg?"". The MoCo Show. July 28, 2017.

- Straight, Susan (February 8, 2013). "Neighborhood Profile: Flints Grove". Washington Post. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "North Potomac CDP". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. February 19, 2008. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "North Potomac Populated Place". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. December 4, 1996. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "Updated World Map of the Koppen-Geiger Climate Classification". Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. European Geosciences Union. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "Gaithersburg, MD Monthly Weather". The Weather Channel. TWC Product and Technology LLC. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- "Freeze / Frost Occurrence Data (Rockville, Maryland)" (PDF). NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- "Census of Population and Housing". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- Census area not separately delineated in 1980.

- "North Potomac CDP, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau, United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- "North Potomac CDP, Maryland – ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates". United States Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau, United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- Zimmermann, Joe (April 17, 2017). "North Potomac and North Bethesda Rank Among Best Places To Live in Maryland". Bethesda Magazine – Bethesda Beat. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- Flynn, Liz (October 1, 2019). "The 20 Best Places to Live in Maryland". Money, Inc. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- U.S. Census Bureau 2012, p. IV-2

- U.S. Census Bureau 2012, p. 42

- U.S. Census Bureau 2012, p. 37

- "QuickFacts – North Potomac CDP, Maryland (All Tables)". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- Montgomery County government (2020). Montgomery County Council Legislative Branch (Map). Rockville, Maryland: Montgomery County Government. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Council – About the Council". Montgomery County Council. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- "North Potomac Citizen's Association – About Us". North Potomac Citizens Association. North Potomac Citizens Association. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Department of Police – 1D-Rockville". Montgomery County Department of Police. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- "City of Rockville – Police". City of Rockville. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- "Montgomery County, Maryland – Fire & Rescue Service". Montgomery County, Maryland government. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- "Rockville Fires Department, Inc. – Westside–Company 31". Montgomery County, Maryland government. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- "North Potomac, CDP, Maryland – Statistics for All U.S. Firms by Industry, Gender, Ethnicity, and Race for the U.S., States, Metro Areas, Counties, and Places: 2012". United States Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- "I 270 Technology Corridor Report". Germantown-Gaithersburg Chamber of Commerce. Germantown-Gaithersburg Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- Peetz, Caitlynn (September 12, 2019). "Travilah Square Shopping Center Sold for $52 Million". Bethesda Magazine. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- "Traville Village Center" (PDF). Beatty Management Company. Beatty Management Company. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "QuickFacts – North Potomac CDP, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau, United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- U.S. Department of Transportation & Maryland Department of Transportation 2002, p. 12

- "Intercounty Connector (ICC)/MD 200". Maryland Transportation Authority – Intercounty Connector (ICC)/MD 200. Maryland Transportation Authority. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "Montgomery, Maryland – Washington DC". MD DC Montgomery, Maryland. Conference and Visitors Bureau of Montgomery County, MD, Inc. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "Metro System Map" (PDF). Metro System Map. Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "Department of Transportation Transit Services – Essential Modified Service Plan Routes". Montgomery County Department of Transportation , Government. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- "Pepco – About Us". Potomac Electric Power Company. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Washington Gas Service Territory". Washington Gas. WGL Holdings, Inc. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "What Does My Montgomery County-Provided Trash Service Include?". Department of Environmental Protection of Montgomery County, Maryland. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Shady Grove Processing Facility and Transfer Station". Department of Environmental Protection of Montgomery County, Maryland. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "WSSC – Project Locations". Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Public Water & Sewer Service (Where Does Your Water Come From?) and (Where Does Your Wastewater Go?)". Department of Environmental Protection of Montgomery County, Maryland. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Adventist HealthCare Shady Grove Medical Center". Adventist HealthCare. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Adventist HealthCare Shady Grove Medical Center Earns Five-Star Rating from Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services". Adventist HealthCare. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Schools – North Potomac Citizens Association". North Potomac Citizens Association. North Potomac Citizens Association. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "Quince Orchard High School Map + Directions". Montgomery County Public Schools. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "Thomas S. Wootton High School Map + Directions". Montgomery County Public Schools. Montgomery County Public Schools. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "US News Best High Schools Rankings – Thomas S. Wootton High". U.S. News & World Report. March 18, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- "The Universities at Shady Grove – About USG". The Universities at Shady Grove. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "The Universities at Shady Grove – USG at a Glance" (PDF). The Universities at Shady Grove. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- "Johns Hopkins University – Montgomery County". Johns Hopkins University – Montgomery County. Johns Hopkins University – Montgomery County. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "Montgomery College". Montgomery College. Montgomery College. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Public Libraries – Quince Orchard Library". Montgomery County Public Libraries. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "The Universities at Shady Grove – Priddy Library". The Universities at Shady Grove. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Public Libraries – Rockville Memorial Library". Montgomery County Public Libraries. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- Ruben, Barbara (April 26, 2001). "Library Celebrates 50th Anniversary". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- Zdravkovska 2011, p. 135

- "Potomac Farms Homeowner's Association – Recreational/Cultural Links". Potomac Farms Homeowner's Association. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- "Montgomery History – Beall-Dawson House". Montgomery County Historical Society. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- "Gaithersburg Community Museum". Gaithersburg, Maryland government. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- Ramanathan, Lavanya; Hahn, Fritz (October 3, 2018). "Going to Glenstone? Here's what you need to know about D.C.'s new must-see art museum". Washington Post. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- Mir, A.; Spivack, Matthew; Mosk, A. (February 6, 2005). "Strathmore A High Note For County". Washington Post. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Nancy H. Dacek North Potomac Recreation Center". Montgomery County Recreation – North Potomac. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- "Potomac Horse Center Special Park". Montgomery County, Maryland – Montgomery Parks. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- "Westleigh Recreation Club". Westleigh Recreation Club. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- "Montgomery County, Maryland – Montgomery Parks – Park Trails". Montgomery County, Maryland – Montgomery Parks. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Montgomery County, Maryland – Montgomery Parks – Muddy Branch Greenway Trail". Montgomery County, Maryland – Montgomery Parks. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- Zimmermann, Joe (January 25, 2018). "Officials Break Ground on Trail Between North Potomac and Germantown". Bethesda Magazine. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "Powerline Trail". Montgomery County, Maryland – Montgomery Parks. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Parks". Montgomery County, Maryland – Montgomery Parks. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- "Muddy Branch Stream Valley Park". Montgomery County, Maryland – Montgomery Parks. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- "Our Pond and Park". Dufief Homeowner's Association. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Amenities". Potomac Crossing Homeowners Association. Vanguard Management Associates, Inc. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "About the Stonebridge HOA". Montgomery County, Maryland – Montgomery Parks. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- "Potomac Farms Homeowner Association PFHOA – Welcome". Potomac Farms Homeowner Association North Potomac, Maryland. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- "Chesapeake & Ohio Canal – National Historical Park". National Park Service. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- "Blockhouse Point Conservation Park & Trails". Montgomery County, Maryland – Montgomery Parks. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- Peck 2012, p. e-book

- "Maryland SoccerPlex & Adventist Healthcare Fieldhouse". Maryland Soccer Foundation, Inc. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

References

- Boyd, T. H. S. (1879). The History of Montgomery County, Maryland, From its Earliest Settlement in 1650 to 1879. Clarksburg, MD [Baltimore]: W.K. Boyle & Son. OCLC 79381943.

- Curtis, Shaun (2020). Around Gaithersburg. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-46710-462-3. OCLC 1124337558.

- Kelly, Clare Lise; Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (2011). Places from the Past: The Tradition of Gardez Bien in Montgomery County, Maryland - 10th Anniversary Edition (PDF). Silver Spring, Maryland: Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. ISBN 978-0-97156-070-3. OCLC 48177160. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- McGuckian, Eileen (2012). Community Cornerstones - A Selection of Historic African American Churches in Montgomery County, Maryland (PDF). Germantown, Maryland: Heritage Montgomery. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Montgomery County Historical Society (1999). Montgomery County, Maryland – Our History and Government (PDF). Rockville, Maryland: Montgomery County Government Office of Public Relations.

- Peck, Garrett (2012). The Potomac River: A History and Guide. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 978-1-61423-787-7. OCLC 945980988. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- U.S. Census Bureau (1973). 1970 Census of Population. Volume 1 : Characteristics of the Population. Part 22 : Maryland. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 27693887. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- U.S. Census Bureau (2003). 2000 Census of Population and Housing, Population and Housing Unit Counts, Maryland. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9781428985810. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- U.S. Census Bureau (2012). Maryland: 2010 - Population and Housing Unit Counts (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 19, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- U.S. Department of Transportation; Maryland Department of Transportation (2002). Multi-Modal Corridor Study, Frederick and Montgomery Counties, Maryland – Draft Environmental Impact Statement and Section 4(f) Evaluation Volume 2 of 2. Baltimore, MD: Maryland Department of Transportation. OCLC 49960675. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- Zdravkovska, Nevenka (2011). Academic Branch Libraries in Changing Times. Oxford, U.K.: Chandos Pub. ISBN 978-1-78063-270-4. OCLC 1047817835.