Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands

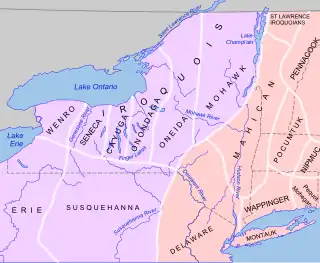

Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands include Native American tribes and First Nation bands residing in or originating from a cultural area encompassing the northeastern and Midwest United States and southeastern Canada.[1] It is part of a broader grouping known as the Eastern Woodlands.[2] The Northeastern Woodlands is divided into three major areas: the Coastal, Saint Lawrence Lowlands, and Great Lakes-Riverine zones.[3]

_by_Charles_Bird_King.jpg.webp)

The Coastal area includes the Atlantic Provinces in Canada, the Atlantic seaboard of the United States, south until North Carolina. The Saint Lawrence Lowlands area includes parts of Southern Ontario, upstate New York, much of the Saint Lawrence River area, and Susquehanna Valley.[3] The Great Lakes-Riverine area includes the remaining inland areas of the northeast, home to Central Algonquian and Siouan speakers.[4]

The Great Lakes region is sometimes considered a distinct cultural region, due to the large concentration of tribes in the area. The Northeastern Woodlands region is bound by the Subarctic to the north, the Great Plains to the west, and the Southeastern Woodlands to the south.[5]

List of peoples

- Abenaki (Tarrantine), Quebec, Maine, New Brunswick, historically Vermont and New Hampshire

- Eastern Abenaki, Quebec, Maine, and historically New Hampshire[6]

- Western Abenaki: Quebec, Massachusetts, historically New Hampshire and Vermont

- Anishinaabeg (Anishinabe, Neshnabé, Nishnaabe) (see also Subarctic, Plains)

- Algonquin,[7] Quebec, Ontario

- Nipissing,[7] Ontario[6]

- Ojibwe (Chippewa, Ojibwa), Ontario, Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin[6]

- Mississaugas, Ontario

- Saulteaux (Nakawē), Ontario

- Odawa people (Ottawa), Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Ontario, also currently Oklahoma;[6] later Oklahoma

- Potawatomi, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan,[6] Ontario, Wisconsin; also currently Kansas and Oklahoma

- Assateague, formerly Maryland[8]

- Attawandaron (Neutral), Ontario[6]

- Beothuk, formerly Newfoundland[6]

- Chowanoke, formerly North Carolina

- Choptank people, formerly Maryland[8]

- Conoy, Virginia,[8] Maryland

- Erie, formerly Pennsylvania, New York[6]

- Etchemin, Maine

- Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), southern Wisconsin, northern Illinois,[6] later Iowa and Nebraska

- Honniasont, formerly Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia

- Hopewell tradition, formerly Ohio, Illinois, and Kentucky, and Black River region, 200 BCE—500 CE

- Housatonic, formerly Massachusetts, New York[9]

- Illinois Confederacy (Illiniwek), Illinois, Iowa, and Missouri;[6] descendants in Oklahoma

- Iroquois Confederacy[7] (Haudenosaunee), Ontario, Quebec, and New York[6]

- Kickapoo, Michigan,[6] Illinois, Missouri, now Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Mexico

- Laurentian (St. Lawrence Iroquoians), formerly New York, Ontario, and Quebec, 14th century—1580 CE

- Lenni Lenape (Delaware), Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, now Ontario and Oklahoma

- Munsee-speaking subgroups, formerly Long Island and southeastern New York[10]

- Canarsie (Canarsee), formerly Long Island New York[11]

- Esopus, formerly New York,[10] later Ontario and Wisconsin

- Hackensack, formerly New York[10]

- Haverstraw (Rumachenanck), New York[12]

- Kitchawank (Kichtawanks, Kichtawank), New York[12]

- Minisink, formerly New York[10]

- Navasink,[12] formerly to the east along the north shore of New Jersey

- Raritan, formerly Westchester County, New York[12]

- Sinsink (Sintsink), formerly Westchester County, New York[12]

- Siwanoy, formerly Massachusetts[12]

- Tappan, formerly New York[13]

- Waoranecks[14]

- Wappinger (Wecquaesgeek, Nochpeem), formerly New York[15][9]

- Warranawankongs[14]

- Wiechquaeskeck, formerly New York[10]

- Unami-speaking subgroups

- Acquackanonk, formerly Passaic River in northern New Jersey

- Okehocking, formerly southeast Pennsylvania[14]

- Unalachtigo, Delaware, New Jersey

- Munsee-speaking subgroups, formerly Long Island and southeastern New York[10]

- Mahican (Stockbridge Mahican)[7] Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont[6]

- Manahoac, Virginia[16]

- Mascouten, formerly Michigan[6]

- Massachusett, formerly Massachusetts[7][17]

- Ponkapoag, formerly Massachusetts

- Meherrin, Virginia,[18] North Carolina

- Menominee, Wisconsin[6]

- Meskwaki (Fox), Michigan,[6] now Iowa

- Mi'kmaq (Micmac), New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Quebec,[6] and Maine

- Mitchigamea, formerly Illinois

- Mohegan,[7] Connecticut

- Monacan, Virginia[19]

- Montaukett (Montauk),[7] New York

- Monyton (Monetons, Monekot, Moheton) (Siouan), West Virginia and Virginia

- Nansemond, Virginia

- Nanticoke, Delaware and Maryland[6]

- Narragansett, Rhode Island[7]

- Niantic, coastal Connecticut[7][17]

- Nipmuc (Nipmuck), Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island[17]

- Nottaway, Virginia[18]

- Occaneechi (Occaneechee), Virginia[18][20][21]

- Pamplico, North Carolina

- Passamaquoddy, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Maine[6]

- Patuxent, Maryland[8]

- Paugussett, Connecticut[7]

- Pawtucket, Massachusetts, New Hampshire

- Naumkeag, Massachusetts

- Penobscot, Maine

- Pennacook, Massachusetts, New Hampshire

- Pequot, Connecticut[7]

- Petun (Tionontate), Ontario[6]

- Piscataway, Maryland[8]

- Pocumtuc, western Massachusetts[17]

- Podunk, New York,[17] eastern Hartford County, Connecticut

- Powhatan Confederacy, Virginia[8]

- Appomattoc, Virginia

- Arrohateck, Virginia

- Chesapeake, Virginia

- Chesepian, Virginia

- Chickahominy, Virginia[18]

- Kiskiack, Virginia

- Mattaponi, Virginia

- Nansemond, Virginia[18]

- Pamunkey, Virginia[18]

- Paspahegh, Virginia

- Powhatan, Virginia

- Quinnipiac, Connecticut,[7] eastern New York, northern New Jersey

- Rappahannock, Virginia

- Sauk (Sac), Michigan,[6] now Iowa, Oklahoma

- Schaghticoke, western Connecticut[7]

- Secotan Outerbanks, North Carolina

- Shawnee, formerly Ohio,[6] Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, currently Oklahoma

- Shinnecock,[7] Long Island, New York[17]

- Stegarake, Virginia[16]

- Stuckanox (Stukanox), Virginia[18]

- Conestoga (Susquehannock), Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, West Virginia[6]

- Tauxenent (Doeg), Virginia[22]

- Tunxis, Connecticut[7]

- Tuscarora, formerly North Carolina, Virginia, currently New York

- Tutelo (Nahyssan), Virginia[18][20]

- Unquachog (Poospatuck), Long Island, New York[17]

- Wabanaki, Maine, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Quebec[7]

- Wampanoag, Massachusetts[7]

- Wangunk, Mattabeset, Connecticut [7]

- Wenro, New York[6][7]

- Wicocomico, Maryland, Virginia

- Wolastoqiyik, Maliseet, Maine, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Quebec[6]

- Wyachtonok, Connecticut, New York[9]

- Wyandot (Huron), Ontario south of Georgian Bay, now Oklahoma, Kansas, Michigan, and Wendake, Quebec

First Nations in Canada

United States Federally Recognized tribes

- Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma

- Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians of the Bad River Reservation, Wisconsin

- Bay Mills Indian Community, Michigan

- Cayuga Nation of New York

- Chickahominy people, Virginia

- Chippewa-Cree Indians of the Rocky Boy’s Reservation, Montana

- Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Oklahoma

- Delaware Nation, Oklahoma

- Delaware Tribe of Indians, Oklahoma

- Eastern Chickahominy, Virginia

- Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

- Forest County Potawatomi Community, Wisconsin

- Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, Michigan

- Hannahville Indian Community, Michigan

- Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Wisconsin

- Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians of Maine

- Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska, also considered a Great Plains tribe

- Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma, also considered a Great Plains tribe

- Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, Michigan

- Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas

- Kickapoo Tribe of Indians of the Kickapoo Reservation in Kansas

- Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma

- Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin

- Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians of the Lac du Flambeau Reservation of Wisconsin

- Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, Michigan

- Little River Band of Ottawa Indians, Michigan

- Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, Michigan

- Mashantucket Pequot Tribe of Connecticut

- Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, Massachusetts

- Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band of Pottawatomi Indians of Michigan

- Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin

- Miami Tribe of Oklahoma

- Mi'kmaq Nation, Maine

- Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, Minnesota

Six component reservations:- Bois Forte Band (Nett Lake)

- Fond du Lac Band, Minnesota, Wisconsin

- Grand Portage Band

- Leech Lake Band

- Mille Lacs Band

- White Earth Band

- Mohegan Indian Tribe of Connecticut

- Monacan, Virginia

- Nansemond, Virginia

- Narragansett Indian Tribe of Rhode Island

- Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi, Michigan

- Oneida Nation of New York

- Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin

- Onondaga Nation of New York

- Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma

- Pamunkey, Virginia

- Passamaquoddy Tribe of Maine

- Penobscot Tribe of Maine

- Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma

- Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, Michigan, Indiana

- Prairie Band of Potawatomi Nation, Kansas

- Prairie Island Indian Community in the State of Minnesota

- Rappahannock, Virginia

- Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin

- Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians, Minnesota

- Sac and Fox Nation, Oklahoma

- Sac and Fox Nation of Missouri in Kansas and Nebraska

- Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan

- St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin

- Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe, New York

- Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Michigan

- Seneca-Cayuga Tribe of Oklahoma

- Seneca Nation of New York

- Shawnee Tribe, Oklahoma

- Shinnecock Nation, New York

- Sokaogon Chippewa Community, Wisconsin

- Stockbridge Munsee Community, Wisconsin

- Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians of New York

- Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians of North Dakota, Montana, North Dakota

- Tuscarora Nation of New York

- Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) of Massachusetts

- Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska

History

Around 200 B.C the Hopewell culture began to develop across the Midwest of what is now the United States, with its epicenter in Ohio. The Hopewell culture was defined by its extensive trading system that connected communities throughout the Eastern region, from the Great Lakes to Florida. A sophisticated artwork style developed for its goods, depicting a multitude of animals such as deer, bear, and birds.[23] The Hopewell culture is also noted for its impressive ceremonial sites, which typically contain a burial mound and geometric earthworks. The most notable of these sites is in the Scioto River Valley (from Columbus to Portsmouth, Ohio) and adjacent Paint Creek, centered on Chillicothe, Ohio.[24] The Hopewell culture began to decline from around 400 A.D. for reasons which remain unclear.[23]

By around 1100, the distinct Iroquoian-speaking and Algonquian-speaking cultures had developed in what would become New York State and New England.[25] Prominent Algonquian tribes included the Abenakis, Mi'kmaq, Penobscot, Pequots, Mohegans, Narragansetts, Pocumtucks, and Wampanoag.[26] The Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Abenaki, and Penobscot tribes formed the Wabanaki Confederacy in the seventeenth century. The Confederacy covered roughly most of present-day Maine in the United States, and New Brunswick, mainland Nova Scotia, Cape Breton Island, Prince Edward Island and some of Quebec south of the St. Lawrence River in Canada. The Western Abenaki live on lands in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Massachusetts of the United States.[27]

The five nations of the Iroquois League developed a powerful confederacy about the 15th century that controlled territory throughout present-day New York, into Pennsylvania and around the Great Lakes.[28] The Iroquois confederacy or Haudenosaunee became the most powerful political grouping in the Northeastern woodlands, and still exists today. The confederacy consists of the Mohawk, Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga, Seneca and Tuscarora tribes.

The area that is now the states of New Jersey and Delaware was inhabited by the Lenni-Lenape or Delaware, who were also an Algonquian people.[29] Most Lenape were pushed out of their homeland in the 18th century by expanding European colonies, and now the majority of them live in Oklahoma.

Culture

The characteristics of the Northeastern woodlands cultural area include the use of wigwams and longhouses for shelter and of wampum as a means of exchange.[30] Wampum consisted of small beads made from quahog shells.

The birchbark canoe was first used by the Algonquin Indians and its use later spread to other tribes and to early French explorers, missionaries and fur traders. The canoes were used for carrying goods, and for hunting, fishing, and warfare, and varied in length from about 4.5 metres (15 feet) to about 30 metres (100 feet) in length for some large war canoes.[31]

The main agricultural crops of the region were the Three Sisters : winter squash, maize (corn), and climbing beans (usually tepary beans or common beans). Originating in Mesoamerica, these three crops were carried northward over centuries to many parts of North America. The three crops were normally planted together using a technique known as companion planting on flat-topped mounds of soil.[32] The three crops were planted in this way as each benefits from the proximity of the others.[33] The tall maize plants provide a structure for the beans to climb, while the beans provide nitrogen to the soil that benefits the other plants. Meanwhile, the squash spreads along the ground, blocking the sunlight to prevent weeds from growing and retaining moisture in the soil.

Prior to contact Native groups in the Northeast generally lived in villages of a few hundred people, living close to their crops. Generally men did the planting and harvesting, while women processed the crops. However, some settlements could be much bigger, such as Hochelaga (modern-day Montreal), which had a population of several thousand people,[34] and Cahokia, which may have housed 20,000 residents between 1050 and 1150 CE.[35]

For many tribes, the fundamental social group was a clan, which was often named after an animal such as turtle, bear, wolf or hawk.[36] The totem animal concerned was considered sacred and had a special relationship with the members of the clan.

The spiritual beliefs of the Algonquians center around the concept of Manitou (/ˈmænɪtuː/), which is the spiritual and fundamental life force that is omnipresent.[37] Manitou also manifest itself as the Great Spirit or Gitche Manitou, who is the creator and giver of all life. The Haudenosaunee equivalent of Manitou is orenda.

See also

Notes

- Trigger, "Introduction" 1

- Mir Tamim Ansary (2001). Eastern Woodlands Indians. Capstone Classroom. p. 4. ISBN 9781588104519.

- Trigger, "Introduction" 2

- Trigger, "Introduction" 3

- "History of Pre-colonial North America." Essential Humanities. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- Sturtevant and Trigger ix

- "Cultural Thesaurus" Archived June 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. National Museum of the American Indian. Accessed April 8, 2014.

- Sturtevant and Trigger 241

- Sturtevant and Trigger 198

- Goddard 72

- Goddard 72 and 237

- Goddard 237

- Goddard 72, 237–238

- Goddard 238

- Goddard 72 and 238

- Sturtevant and Fogelson, 290

- Sturtevant and Trigger 161

- Sturtevant and Fogelson, 293

- Fogelson and Sturtevant 81

- Sturtevant and Fogelson, 291

- Sturtevant and Trigger 96

- Sturtevant and Trigger 255

- "Hopewell Culture". Ohio History Central. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- "m7/98 Encyclopedia of North American Prehistory M". Archived from the original on October 20, 2009. Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- Klein, Milton M. (ed.) and the New York State Historical Association, The Empire State: A History of New York, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, 2001, ISBN 0-8014-3866-7

- Bain, Angela Goebel; Manring, Lynne; and Mathews, Barbara. Native Peoples in New England. Retrieved July 21, 2010, from Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association.

- Toensing, Gale Courey. "Sacred fire lights the Wabanaki Confederacy", Indian Country Today (June 27, 2008), ICT Media Network

- Horatio Gates Spafford, LL.D. A Gazetteer of the State of New-York, Embracing an Ample Survey and Description of Its Counties, Towns, Cities, Villages, Canals, Mountains, Lakes, Rivers, Creeks and Natural Topography. Arranged in One Series, Alphabetically: With an Appendix… (1824), at Schenectady Digital History Archives, selected extracts, accessed December 28, 2014

- "Native People of New Jersey". ALHN New Jersey. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- Northeast American Indian Facts Native American Indian Facts Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- "Canoe". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- Mount Pleasant, Jane (2006). "The science behind the Three Sisters mound system: An agronomic assessment of an indigenous agricultural system in the northeast". In Staller, John E.; Tykot, Robert H.; Benz, Bruce F. (eds.). Histories of Maize: Multidisciplinary Approaches to the Prehistory, Linguistics, Biogeography, Domestication, and Evolution of Maize. Amsterdam: Academic Press. pp. 529–537. ISBN 978-1-5987-4496-5.

- Hill, Christina Gish (November 20, 2020). "Returning the 'three sisters' – corn, beans and squash – to Native American farms nourishes people, land and cultures". The Conversation. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- Northeast Indian Culture Khan Academy. Retrieved March 7, 2019

- "Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site". UNESCO. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- Northeast Indian Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved March 7, 2019

- Bragdon, Kathleen J. (2001). The Columbia Guide to American Indians of the Northeast. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 18.

References

- Trigger, Bruce C. "Introduction." William C. Sturtevant, general ed. Handbook of North American Indians. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1978.

- Trigger, Bruce, volume ed. Sturtevant, William C., general ed. Handbook of North American Indians. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1978.