Northern jacana

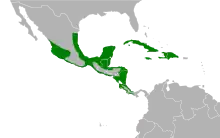

The northern jacana or northern jaçana (Jacana spinosa) is a wader which is known as a resident breeder from coastal Mexico to western Panama, and on Cuba, Jamaica and Hispaniola in the Caribbean. It sometimes known to breed in Texas, United States, and has also been recorded on several occasions as a vagrant in Arizona. The jacanas are a group of wetland birds, which are identifiable by their huge feet and claws, which enable them to walk on floating vegetation in the shallow lakes that are their preferred habitat. In Jamaica, this bird is also known as the 'Jesus bird', as it appears to walk on water.[3] Jacana is Linnæus' scientific Latin spelling of the Brazilian Portuguese jaçanã, pronounced [ʒasaˈnɐ̃], from the Tupi name of the bird. See jacana for pronunciations.

| Northern jacana | |

|---|---|

| |

| In Tortuguero National Park, Costa Rica | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Jacanidae |

| Genus: | Jacana |

| Species: | J. spinosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Jacana spinosa | |

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Fulica spinosa Linnaeus, 1758 | |

Description

The northern jacana has a dark brown body with a black head and neck. In addition its bill has yellow patches and its forehead has a yellow wattle.[4] Its bill has a white base. When a jacana is in flight, its yellowish-green primary and secondary feathers are visible. Also visible are yellow bony spurs on the leading edge of the wings, which it can use to defend itself and its young. The greenish colour of the wing feathers is produced by a pigment, rather rare in birds, called zooprasinin, a copper containing organic compound.[5]

Juveniles have a white supercilium and white lores. The female jacana is around twice as big as the male, averaging 145.4 g (5.13 oz) compared to 86.9 g (3.07 oz).[6] Jacanas average 241 mm (8 inches) in length with a wingspan averaging 508 mm (20 inches).

Young jacana chicks are covered in down and have patterns of orange, browns, black and some white on them. Older chicks are gray and have brownish upper parts.[7]

Distribution and habitat

The northern jacana ranges Mexico to Panama, although they occasionally visit the southern United States,[8] with vagrants being seen in places such as Arizona.[9] It mainly lives in coastal areas. Jacanas live on floating vegetation in swamps, marshes, and ponds.[4]

Behavior and ecology

.jpg.webp)

Feeding

The northern jacana feeds on insects on the surface of vegetation and ovules of water lilies.[4] It also consumes snails, worms, small crabs, fish, mollusks, and seeds. The jacana competes with birds of a similar diet like the sora.[10]

Breeding

The northern jacana is unusual among birds in having a polyandrous society. A female jacana lives in a territory that encompasses the territories of 1–4 males.[11] A male forms a pair bond with a female who will keep other females out of his territory. Pair bonds between the female and her males remain throughout the year, even outside of breeding. These relationships last until a male or female is replaced.[4] The female maintains bonds with her mates though copulations and producing clutches for them, as well as protecting their territories and defending the eggs from predators.[11] Monogamous pairs are sometimes observed among polyandrous groups.[12] The jacana has a simultaneous polyandrous mating system. That is the female will mate with several males a day or form pair bonds with more than one male at a time.[12] Because of the high energy costs of producing eggs, females are replaced more often than males.[13] If water levels remain constant, jacanas can breed year round.[4]

The male[4] constructs a floating nest[14] with whatever plant matter he can find.[4] A male jacana will grab vegetation and walk backwards to uproot it and continues to walk backward to drop the plant part in the nest. The male pushes against and steps on the plant parts to create a compact mount. The best nest are ones that are the most dense and stable.[15] A male may create several nests at different sites and the female may choose one or find a site of her own in the territory.[15]

This bird lays a clutch of four brown eggs with black markings. These eggs usually measure around 30 by 23 millimetres (1.18 by 0.91 in). The male incubates the eggs for 28 days.[14] A female may sometimes shade and squat over the eggs but rarely incubate them.[15] A female may reluctantly incubate the eggs if a male does not have sufficient time to forage throughout the day due to rain and cool temperatures.[11] Males spend most of their time within their territory during incubation but sometimes leave the nest unattended for long periods of time. A male performs when each egg hatches and stands next to the nest to peer into it.[16] The males continues to incubate the remaining eggs while brooding the hatched chicks. When all the eggs have hatched, the male will dispose of the remaining egg shells. It will also lead the chicks away from the nest within the next 24 hours.[16]

Chicks are able to swim, dive and feed shortly after they hatch. The male will not feed the chick but lead them to food. The male will brood the chicks for many weeks. As the chicks get bigger, fewer can fit under the male's wing. Females may brood chicks when the male is away. Territorial defense for both males and females increase when the chicks are born. Males are intolerant of intruders in their territory and make calls to the female for help for predator defense.[16] Females respond to every call the male makes and invest much interest in the safety of the chicks, despite having little interaction with them. The females provide the males with a new clutch when the chicks are 12–16 weeks old.[4]

Predation

Predators of the jacana include snakes, caimans, snapping turtles and various large birds and mammals.[4]

Vocalizations

Vocalizations among jacanas usually occur between mating pairs or between fathers and their young. Jacanas will emit "clustered-note calls", which are made of individual notes clustered together, when jacanas attack intruders in their territories. Jacanas also made calls when eggs or chicks are under threat by predators. The notes and their pattern depend on the urgency of the threat. Calls are also made on flight, when a female is away from the territory too long or if a male cannot find a chick.

Status

Northern jacanas appear to be common throughout most of their range, but could become vulnerable with loss of wetlands.[8]

References

- BirdLife International (2020). "Jacana spinosa". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22693550A168911151. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22693550A168911151.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Avibase "Northern Jacana – Synonyms"

- Great Adventures, Saint Elizabeth, Jamaica

- Janzen, D.H., Ed. (1983). Costa Rican Natural History. Chicago and London, U Chicago Press.

- Dyck, Jan (1992). "Reflectance Spectra of Plumage Areas Colored by Green Feather Pigments" (PDF). The Auk. 109 (2): 293–301. doi:10.2307/4088197. JSTOR 4088197.

- Jenni, D.A.; Collier, G. (1972). "Polyandry in the American Jacana (Jacana spinosa)" (PDF). The Auk. 89: 743–765. doi:10.2307/4084107. JSTOR 4084107.

- Gardner D. Stout, Peter Matthiessen, Ralph Simon Palmer, Eds. (1967). The Shorebirds of North America. Viking Press.

- Kaufman, K. 1996. Lives of North American birds. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- "Northern Jacana".

- Stephens, M.L. (1984). "Interspecific aggressive behavior of the polyandrous Northern Jacana (Jacana spinosa)." The Auk 101:508-518.

- Betts, B.J. and Jenni, D.A. (1991). "Time budgets and the adaptiveness of polyandry in the Northern Jacana." Wilson Bulletin 103 (4): 578-597.

- Jenni, D.A. (1974). "Evolution of polyandry." American Zoologist 14:129-144.

- Jenni, D.A. and Collier, G. (1972). "Polyandry in the American Jacana (Jacana spinosa). " The Auk 89:743-765.

- Hauber, Mark E. (1 August 2014). The Book of Eggs: A Life-Size Guide to the Eggs of Six Hundred of the World's Bird Species. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-226-05781-1.

- Jenni, D.A. and Burr, B.J. (1978). "Sex differences in nest construction, incubation, and parental investment in the polyandrous American Jacana (Jacana Spinosa). " Animal Behavior 26 (1): 207-218.

- Jenni, D.A. (1979) "Female chauvinist birds. " New Scientist 82: 896-899.

- Shorebirds by Hayman, Marchant and Prater ISBN 0-395-60237-8

External links

- 1840s illustration by P. Oudart, titled as "Parra cordifera (Lesson)".