Northern masked owl

The northern masked owl (Tyto novaehollandiae kimberli) is a large forest owl in the family Tytonidae. The northern kimberli subspecies was identified as a novel race of the Australian masked owl by the Australian ornithologist Gregory Macalister Mathews in his 1912 reference list of Australian birds.[1] The northern masked owl occurs in forest and woodland habitats in northern Australia, ranging from the northern Kimberley region to the northern mainland area of the Northern Territory and the western Gulf of Carpentaria.[2][3] While the Australian masked owl is recognized as the largest species in the family Tytonidae (barn owls), the northern masked owl is one of the smallest of the Australian masked owl subspecies.

| Northern masked owl | |

|---|---|

| |

| At Groote Eylandt, off the coast of Australia's Northern Territory | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Strigiformes |

| Family: | Tytonidae |

| Genus: | Tyto |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | T. n. kimberli |

| Trinomial name | |

| Tyto novaehollandiae kimberli | |

| |

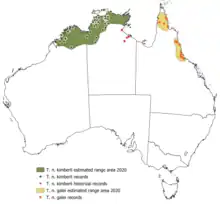

| Tyto novaehollandiae kimberli range[2] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

The northern masked owl is a subspecies of the Australian masked owl (Tyto novaehollandiae), a large tytonid owl which resembles the barn owl.[4] The Australian masked owl ranges over non-arid areas of the Australian continent, southern Papua New Guinea and a number of islands north of Papua New Guinea and in the eastern Indonesian archipelago.[5] Eight subspecies of Tyto novaehollandiae have been recognised, however there has been confusion over the status and inclusion of a number of previously described populations as independent species or subspecies.[4][6] Species level taxa that are now considered to be subspecies of Tyto novaehollandiae include T. manusi and T. sororcula.[6] The relationships between the northern Australian subspecies and populations are unresolved.[7][8]

In 1912 Mathews[1][9] identified eight subspecies of masked owl in Australia, including T. n. castanops, T. n. kimberli, T. n. melvillensis, T. n. mackayi, T. n. novaehollandiae, T. n. perplexa, T. n. riordani and T. n. whitei, based on observations of distribution, morphology and plumage. Two additional races were subsequently described, including T. n. galei (Mathews 1914) from Cape York Peninsula[10] and T. n. troughtoni (Cayley 1931) from the Nullarbor plain region of South Australia/Western Australia.[11] Recent taxonomic revisions recognise only four of these subspecies as occurring in Australia, including T. n. novaehollandiae (eastern and southern mainland, southwest Western Australia), T. n. castanops (Tasmania), T. n. melvillensis (Tiwi Islands) and T. n. kimberli (northern Australia including Kimberly, Top End and Cape York).[6] Four extralimital races of the Australian masked owl are also recognised, including T. n. calabyi (Mason, 1983) from southern Papua New Guinea, T. n. manusi (Rothschild & Hartert, 1914) from the Admiralty Islands group (PNG), T. n. sororcula (Sclater, 1883) from the Tanimbar Islands (Indonesia) and T. n. cayelii (Hartert, 1900) from Buru Island (Indonesia).[4]

Australian masked owls from Cape York Peninsula have been separated as the subspecies T. n. galei by some authors,[12] however some authorities include this population with T. n. kimberli.[4] The central Queensland subspecies T. n. mackayi (Mathews 1912) may also considered to be synonymous with T. n. kimberli.[13] The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2020 treats Tyto novaehollandiae kimberli as separate from the Cape York and wet tropics race T. n. galei, however the relationship between these subspecies requires further investigation.[3][8]

Description

Mathews[1] described the northern masked owl as being smaller and paler than the nominate race of the Australian masked owl (T. novaehollandiae novaeholladiae). Subsequent observations have confirmed that the northern masked owl is small in size when compared to other Australian masked owl races, with the exception of the Tiwi masked owl (Tyto novaehollandiae melvillensis). Based on data recorded on museum specimen labels and reported in the Handbook of Australian and New Zealand Birds, female northern masked owls weigh approximately 700 g (25 oz) and males approximately 450 g (16 oz). This is considerably lighter than the Tasmanian masked owl, with race castanops females weighing up to 1,260 g (44 oz) and males weighing up to 800 g (28 oz).[4]

Range and distribution

The northern masked owl is uncommon and widely dispersed across broad areas of northern Australia, with the main areas of distribution including the north-west Kimberley region of Western Australia, the northern section of the Northern Territory between the Victoria River and eastern Arnhemland, and Groote Eylandt in the east. Significant populations occur in the north-west of the Kimberley, the Northern Territory mainland between Victoria River and Kakadu National Park, Garig Gunak Barlu National Park (Coburg Peninsula) and Groote Eylandt.[2][3] Island populations are known from Augustus and Koolan Islands in the Kimberley region of Western Australia and Groote Eylandt, Akwamburkba (Winchelsea Island) and North Goulburn Islands in the Northern Territory. The historical distribution extended to the Borroloola region in the eastern Northern Territory, but the veracity of these records is undetermined.[3] Several early historical specimens labelled from this region are held in museum collections but recent surveys in the Borroloola area and at Pungalina Station failed to detect northern masked owls.[14] In 2019 and 2020 there were confirmed northern masked owl records from Groote Eylandt, north-eastern Arnhemland, Kakadu National Park and the Mitchell Plateau and Yampi Peninsula in Western Australia.[3]

Habitat

Northern masked owl predominantly forage in eucalypt open forests and woodlands with open understories and roost in closed monsoon forests and tree hollows.[3][15][4][16] Foraging also occurs in more open habitats and masked owls have also been recorded in Melaleuca forests, rainforest, riparian forest, grasslands, mangroves, grassland and coastal dunes.[4][15] In the Northern Territory, northern masked owls frequently occur in Darwin stringybark (Eucalyptus tetrodonta) and Darwin woollybutt (Eucalyptus miniata) tall open forest.[3][15][17] On Groote Eylandt they are mainly observed foraging in tall open forest and woodland, on the margins of sandstone escarpments and one occasion on beach dunes adjacent to open forest.[3][17]

Behaviour and ecology

Home range

The south-eastern nominate race of the Australian masked owl has a home range of 5–10 km2.[18] and it is speculated that the range of the northern masked owl could cover a similar area.[15] Relatively high densities of northern masked owls have been detected on Groote Eylandt, with a home range estimate of 4–5 km2 based on sampling across several large forest grids covering approximately 5000 ha. Surveys indicate lower densities and predicted larger home range areas on Coburg peninsula and very low densities at other Northern Territory mainland range areas.[3]

Roost and nest sites

Northern masked owls maintain diurnal roosts in hollows in the trunk or near-vertical spouts of large live or dead canopy trees.[4][15] Northern masked owls also roost on branches in dense vegetation, including in monsoon vine forests and riparian vegetation on drainage lines.[4] Recently discovered roost sites in the Kimberley have all been associated with tall Melaleuca gallery (riparian) forest adjacent to sandstone escarpments and open savannah woodland.

Foraging and diet

The diet of the northern masked owl is poorly known, although is presumed to be similar to that of the southern Australian masked owl subspecies, which feed mostly on small to medium-sized terrestrial mammals and take smaller percentages of scansorial and arboreal mammals, insects and birds.[4] Stomach contents of two northern masked owl specimens from the Kimberley contained small birds and marsupials including savanna glider (Petaurus ariel).[19] Northern masked owl have been observed consuming brush-tailed rabbit-rat on Groote Eylandt.[3]

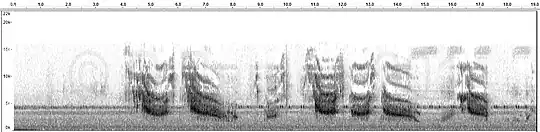

Vocalisation

Several northern masked owl call variations have been observed in the field. The most common call is a loud, extended rasping screech that is given while perching or in flight and is possibly used in territorial defense and/or as a contact call. [4] A "chatter" call, described as a loud cackle or continuous chatter,[4] is likely to be associated with courtship display flights by male birds circling over breeding territory (based on other Australian masked owl subspecies)[4] and is sometimes given in response to call broadcast during surveys. Other social calls are poorly known but are likely to be similar to those documented for other Australian masked owl subspecies, including extended high pitched trills, rasping and stuttered hissing when approaching young in the nest or to solicit feeding, churrs and hissing during nest defence and low pitched cooing during mating and courtship.[4]

Conservation status and threats

IUCN assessment and legislative status

The IUCN (2018) has assessed the Australian masked owl (Tyto novaehollandiae) as 'least concern' but has not provided subspecific status assessments.[20] The northern masked owl is listed as a vulnerable species under the Commonwealth EPBC Act 1999,[21] vulnerable in Queensland[22] and vulnerable in the Northern Territory.[23]

The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2020 assessed the status of the northern masked owl as vulnerable C2a(i), finding that despite the discovery of a relatively high-density population on Groote Eylandt, declining prey populations on the mainland are likely to be causing ongoing declines. The infrequency of confirmed sightings of this subspecies on the mainland suggests that there is a high level of uncertainty in terms of status and trends.[3]

Population status

The northern masked owl appears to be uncommon across most of its range, and a recent population estimate for the Northern Territory and Western Australian distribution (excluding Queensland populations) ranges from 2000 to 5000 mature individuals. There are a limited number of localities where the northern masked owl appears to remain relatively common, including Garig Gunak Barlu National Park, the north-west Kimberley and the Anindilyakwa Indigenous Protected Area (Groote Eylandt). These sites are likely to represent important refuge areas for northern masked owl populations and have potentially been less impacted by fire regime changes, disturbance from pastoralism, feral animals and decline of prey species that has been documented at other locations.[3]

Threats

Identified and potential threats to populations of the northern masked owl are related to the direct and indirect actions of humans (Homo sapiens), including land clearing, altered fire regimes, stocking with exotic ruminants, proliferation of feral animals and weeds and atmospheric pollution leading to global heating.

The main threat to northern masked owl populations is thought to be the decline in the availability of mammalian prey[24] linked to more frequent and extensive fires and predation by feral cats,[25] exacerbated in some places by feral herbivore and cattle grazing[26] and weed encroachment.[16] The only sites where prey remain relatively abundant are Groote Eylandt[27] and the Kimberley.[28] The large trees and hollows required for nesting may be reduced in number due to the current regime of more intense and frequent fires. However, these trees continue to be abundant[29] and highly mobile species with large home range areas such as northern masked owls may be less vulnerable to local impacts of fire on key habitat resources.[30] Mining exploration licences and active mining titles cover broad areas of northern masked owl range, including most of Groote Eylandt and Winchelsea Island, and components of north-eastern Arnhemland, Batchelor/Pine Creek, Daly, north-west Kimberley and Yampi regions.[3]

The northern masked owl was ranked as having a medium level of sensitivity to the impacts of global heating in a study conducted by the Australian National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility.[31]

Conservation reserves

The northern masked owl has been recorded in several of conservation reserves, including the Mitchell River National Park (WA), Lawley River National Park (WA), Kakadu National Park (NT), Garig Gunak Barlu National Park (Coburg Peninsula) (NT), Keep River National Park (NT), Judbarra/Gregory National Park (NT) and Nitmiluk National Park (NT).[2][3] Northern masked owls are present in a number of private conservation reserves managed by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy, including reserves at Mornington Station, Yampi and Artesian Range/Charnley River in the Kimberley.[2]

Northern masked owls were recorded on Groote Eylandt in 2010[17] and on Akwamburkba (Winchelsea Island) in 2018 within the Anindilyakwa Indigenous Protected Area. Northern masked owl occur in other Indigenous Protected Areas and Indigenous lands, including the Anindilyakwa, Arrabrkbi, Birriwinjku, Bunubu, Dambimangari, Gagudju, Garawa, Kundjeyhmi, Jawoyn, Kamu, Karde, Yek Diminin, Kenbi, Koonguruku, Labarganyan, Larrakia, Limilngan, Malak, Maranunggu, Mayala, Mirarr, Ngan'gi, Ngombur, Ngumbarl, Nimanburr, Rakpeppimenarti, Uunguu, Waanyi, Wagiman, Warai, Warrwa, Wilinggin, Wulna, Wunambal, Gaambera and Yammirr.[3]

References

- Mathews, Gregory (1912). "A Reference-List of the Birds of Australia". Novitates Zoologicae. XVIII (3): 171-455. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.1694.

- Tyto (Megastrix) novaehollandiae kimberli spatial data. Atlas of Living Australia (2020).

- Barden, Paul; Jackett, Nigel; Garnett, Stephen (2021). Northern Masked Owl Tyto novaehollandiae kimberli. In Action Plan for Australian Birds 2020. (Eds ST Garnett, GB Baker). Melbourne: CSIRO.

- Higgins, P.J. ed (1999). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 4. Parrots to Dollarbirds. Oxford University Press, Melbourne.

- BirdLife International. (2018). Tyto novaehollandiae. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T62172196A132190206.en

- del Hoyo, J. Collar, N. J. Christie, D. A. Elliott, A. Fishpool, L. D. C. (2014). HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World. Lynx Edicions BirdLife International.

- Jackett, N; Murphy, S. A.; Leseberg, N. P.; Watson, J. E. M. (2020). "A review of vegetation associated with records of the Masked Owl Tyto novaehollandiae in north-eastern Queensland". Australian Field Ornithology. 37: 184–189. doi:10.20938/afo37184189.

- Uva, V; Päckertb, M; Ciboisc, A; Fumagallia, L; Roulina, A (2018). "Comprehensive molecular phylogeny of barn owls and relatives (Family: Tytonidae), and their six major Pleistocene radiations". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 125: 127–137. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2018.03.013. PMID 29535030.

- Mathews, Gregory (1912). "Additions and corrections to my reference list to the Birds of Australia". Austral Avian Records. 1: 25-61.

- Mathews, Gregory (1914). "Additions to A List of the Birds of Australia". South Australian Ornithology. 1 (2): 12-13.

- Cayley, N. (1931). What bird is that?: a guide to the birds of Australia. Angus and Robertson.

- Schodde R., Mason I.J. (Eds) (1997). Zoological Catalogue of Australia 37.2: Aves (Columbidae to Coraciidae). CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne. ISBN 978-0643060371

- Mees, G. F. (1964). "A Revision of the Australian Owls (Strigidae and Tytonidae)" (PDF). Zoologische Verhandelingen. 65: 3-61.

- Barden, Paul (2020). Northern Masked Owl Survey and Incidental Microbat Trapping Pungalina Station November 2016. Report to Australian Wildlife Conservancy. Darwin: EMS.

- Woinarski, J.; Ward, S. (2012). Threatened Species of the Northern Territory Masked Owl (northern Australian mainland subspecies) Tyto novaehollandiae kimberli (PDF). Darwin: Northern Territory Government.

- Woinarski, J.C.Z.(2004). National Multi-species Recovery plan for the Partridge Pigeon (eastern subspecies) Geophaps smithii, Crested Shrike-tit (northern subspecies) Falcunculus (frontatus) whitei, Masked Owl (north Australian mainland subspecies) Tyto novaehollandiae kimberli; and Masked Owl (Tiwi Islands subspecies) Tyto novaehollandiae melvillensis, 2004 – 2008. Northern Territory Department of Infrastructure Planning and Environment, Darwin.

- Barden, Paul (2012). Flora and Fauna Survey Western Groote Eylandt 2010 – 2012 Birds. Report to GEMCO/BHP. Darwin: EMS.

- Kavanagh, R. P.; Murray, M (1996). "Home range, habitat and behaviour of the masked owl Tyto novaehollandiae near Newcastle, New South Wales". Emu. 96 (4): 250–257. doi:10.1071/MU9960250.

- Johnstone, G. M.; Storr, R. E. (1998). "Non-passerines: (Emu to Dollarbird)". Western Australian Museum.

- Birdlife International, IUCN. "Tyto novaehollandiae. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T62172196A132190206". IUCN Red List. IUCN/Birdlife International. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- Tyto novaehollandiae kimberli – Masked Owl (Northern). Species Profile and Threats Database. Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra (2020)

- Queensland Nature Conservation (Wildlife) regulation 2006. Government of Queensland (2006).

- Territory Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 2000. As in force at 13 November 2014. Northern Territory Government (2015)

- Woinarski, J. C.; Legge, S; Fitzsimons, J. A.; Traill, B. J.; Burbidge, A. A.; Fisher, A; Firth, R. S.; Gordon, I. J.; Griffiths, A. D.; Johnson, C. N.; McKenzie, N. L. (2011). "The disappearing mammal fauna of northern Australia: context, cause, and response". Conservation Letters. 4 (3): 192–201. doi:10.1111/j.1755-263X.2011.00164.x. hdl:1885/50336.

- Leahy, L.; Legge, S. M.; Tuft, K; McGregor, H. W.; Bartuma, L.A.; Jones, M.E.; Johnson, C. N. (2016). "Amplified predation after fire suppresses rodent populations in Australia's tropical savannas". Wildlife Research. 48 (2): 705–716. doi:10.1071/WR15011. S2CID 88162792.

- Legge, S; Smith, J. G.; James, A; Tuft, K. D.; Webb, T; Woinarski, J. C. (2019). "Interactions among threats affect conservation management outcomes: Livestock grazing removes the benefits of fire management for small mammals in Australian tropical savannas". Conservation Science and Practice. 1 (7): 52. doi:10.1111/csp2.52.

- Heiniger, J; Davies, H. F.; Gillespie, G. R. (2020). "Status of mammals on Groote Eylandt: Safe haven or slow burn?". Austral Ecology. 45 (6): 759–772. doi:10.1111/aec.12892.

- Start, A. N.; Burbidge, A. A.; McDowell, M. C.; McKenzie, N. L. (2012). "The status of non-volant mammals along a rainfall gradient in the south-west Kimberley, Western Australia". Australian Mammalogy. 34: 36–48. doi:10.1071/AM10026.

- Woolley, L. A.; Murphy, B. P.; Radford, I. J.; Westaway, J; Woinarski, J. C. Z. (2018). "Cyclones, fire, and termites: The drivers of tree hollow abundance in northern Australia's mesic tropical savanna". Forest Ecology and Management. 419: 146–159. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2018.03.034.

- Woinarski, J. C.; Russell-Smith, J.; Andersen, A. N.; Brennan, K (2009). J Russell-Smith; PJ Whitehead; PM Cooke (eds.). Fire management and biodiversity of the western Arnhem Land Plateau. Darwin: CSIRO Publishing. pp. 201–228. ISBN 9780643094024.

- Garnett, Stephen; Franklin, D; Ehmke, G; VanDerWal, J; Hodgson, L; Pavey, C; Reside, A; Welbergen, J; Butchart, S; Perkins, G; Williams, S (2013). Climate change adaptation strategies for Australian birds (PDF) (NCCARF Publication 43/13 ed.). Gold Coast: National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility. ISBN 978-1-925039-14-6.