Mass media in Norway

Mass media in Norway outlines the current state of the press, television, radio, film and cinema, and social media in Norway.

| Part of a series on |

| Norwegians |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| Diaspora |

| Other |

| Norwegian Portal |

Press

Reporters Without Borders ranks Norway 1st in its Worldwide Press Freedom Index. Freedom of the press in Norway dates back to the constitution of 1814. Most of the Norwegian press is privately owned and self-regulated; however, the state provides press support.

Television

The two companies dominating the Norwegian terrestrial broadcast television are the government-owned NRK (with four main services, NRK1, NRK2, NRK3 and NRK Super) and TV2 (with TV 2 Filmkanalen, TV 2 Nyhetskanalen, TV 2 Sport, TV 2 Zebra and TV 2 Livsstil). Other, long-running channels are TVNorge and TV3.

Radio

National radio is dominated by the public-service company NRK, which is funded from the television licence fee payable by the owners of television sets. NRK provides programming on three radio channels – NRK P1, NRK P2, and NRK P3 – broadcast on FM and via DAB. A number of further specialist channels are broadcast exclusively on DAB, DVB-T, and the internet including Radio Norway Direct Norway's new English language Radio Station.

Additionally, there are a number of commercial radio stations as well as local radio stations run by various non-profit organizations.

Social media

As of June 2023, it is estimated that 3.4M Norwegians use Facebook.[1] For comparison, the total number of inhabitants is about 5,504,329 people

Institutions

Institutions within organized labour are the Norwegian Union of Journalists, the Association of Norwegian Editors and the Norwegian Media Businesses' Association—these are organized in the umbrella Norwegian Press Association. The Press Association is responsible for Pressens Faglige Utvalg, which oversees the Ethical Code of Practice for the Norwegian Press. The Broadcasting Council oversees the state-owned Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. The Norwegian Media Authority contributes to the enforcement government regulations.

Media bias

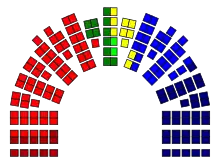

Distribution of mandates after the actual 2009 Norwegian parliamentary election:

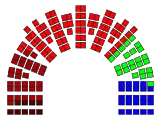

Distribution of mandates after the actual 2009 Norwegian parliamentary election: Distribution of mandates by Norwegian journalists sympathies before the 2009 Norwegian parliamentary election:

Distribution of mandates by Norwegian journalists sympathies before the 2009 Norwegian parliamentary election:

As with other related countries, the Norwegian media is often criticized of being biased towards the political left. Political scientist Frank Aarebrot claims to present evidence of this in terms of both Norwegian journalists and editors.[2] Aarebrot has said that "it is serious when Norwegian journalists massively support the political left, but it is a bit more serious when it actually to a greater degree applies to Norwegian editors than among the journalists". He also expressed concern that journalists who sympathise with the Progress Party may have a lesser chance to get hired than journalists with political sympathies close to editors.[3]

For instance, in the actual 2009 election, the Progress Party received 41 mandates, while by journalists it would have received none. The Christian Democratic Party and Center Party would also have been left without representation, while the revolutionary socialist party Red would enter parliament with 9 mandates. The Socialist Left and Liberal Party would also receive significant gains.[2] In 2003, as much as 36% of Norwegian journalists said they would vote for the Socialist Left Party alone, with only 25% saying that they would vote for any of the right-of-center Liberal, Christian Democratic, Conservative or Progress Party combined.[3] News commentator Frank Rossavik once said that if a journalist would stand forward as a Progress Party voter, it would have been "social suicide", and more devastating than withdrawing from the Norwegian Union of Journalists.[4]

Norwegian editors have as well been proven to have leftist political views, with a 2008 survey showing that the Labour Party would have been given a majority in parliament alone with 85 representatives.[3]

The notion of political bias based on the sum of individuals' party selection has been criticized. Among others, conservative historian and politician Francis Sejersted holds that the general media is neither left-slanted nor right-slanted, but "media-slanted". This means that media across the political spectrum have a tendency to choose the same angle on a case, focusing on personification and dramatic events.[5]

Regulation

The media systems in Scandinavian countries are twin-duopolistic with powerful public service broadcasting and periodic strong government intervention. Hallin and Mancini introduced the Norwegian media system as Democratic Corporatist.[6] Newspapers started early and developed very well without state regulation until the 1960s. The rise of the advertising industry helped the most powerful newspapers grow increasingly, while the little publications were struggling at the bottom of the market. Because of the lack of diversity in the newspaper industry, the Norwegian Government took action, affecting the true freedom of speech. In 1969, Norwegian government started to provide press subsidies to small local newspapers.[7] But this method was not able to solve the problem completely. In 1997, compelled by the concern of the media ownership concentration, Norwegian legislators passed the Media Ownership Act entrusting the Norwegian Media Authority the power to interfere the media cases when the press freedom and media plurality was threatened. The Act was amended in 2005 and 2006 and revised in 2013.

The basic foundation of Norwegian regulation of the media sector is to ensure freedom of speech, structural pluralism, national language and culture and the protection of children from harmful media content.[8][9] Relative regulatory incentives includes the Media Ownership Law, the Broadcasting Act, and the Editorial Independence Act. NOU 1988:36 stated that a fundamental premise of all Norwegian media regulation is that news media serves as an oppositional force to power. The condition for news media to achieve this role is the peaceful environment of diversity of editorial ownership and free speech. White Paper No.57 claimed that real content diversity can only be attained by a pluralistically owned and independent editorial media whose production is founded on the principles of journalistic professionalism. To ensure this diversity, Norwegian government regulates the framework conditions of the media and primarily focuses the regulation on pluralistic ownership.See also

- Lists

References

- "Facebook Users by Country 2023". worldpopulationreview.com. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- Sletta, Kjell (7 May 2009). "Frp-fritt på Stortinget hvis journalister fikk bestemme". Dagbladet.

- Løset, Kjetil (18 April 2008). "Redaktører vil ha Jens". TV2.

- Rossavik, Frank (30 August 2007). "Venstrevridde journalister". Bergens Tidende. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- Nore, Aslak (3 March 2004). "Konserntrusselen". Klassekampen (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- Hallin, D.; Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridgeshire: Cambridge University Press.

- "Medienorge". MiediaNorway. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- Syvertsen, T. (2004). "Eierskapstilsynet – en studie av medieregulering i praksis [Ownership oversight: A study of media regulation in practice]".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Krumsvik, Arne (2011). "Medienes privilegier – en innføring i mediepolitikk [Media Privileges: An Introduction to Media Politics]".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Further reading

in English

- "Norway: Press". Europa World Year Book. Europa Publications. 2004. ISBN 978-1-85743-255-8.

- Euromedia Research Group; Mary Kelly; et al., eds. (2004). "Norway". Media in Europe (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-0-7619-4132-3.

- Gina Dahl [in Norwegian] (2011). Books in Early Modern Norway. Brill. ISBN 9789004207202.

in Norwegian

- Encyclopedias

- Henriksen, Petter, ed. (2007). "Norge – massemedier". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget.

- Books

- Østbye, Helge (1984). Massemediene (in Norwegian). Oslo: Tiden. ISBN 82-10-02375-6.

- Eide, Martin (1995). Blod, sverte og gledestårer. VG, Verdens Gang 1945-95 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Schibsted. ISBN 82-516-1557-7.

- Ottosen, Rune (1996). Fra fjærpenn til Internett. Journalister i organisasjon og samfunn (in Norwegian). Oslo: Aschehoug. ISBN 82-03-26128-0.

- Allern, Sigurd (1997). Når kildene byr opp til dans. Søkelys på PR-byråene og journalistikken (in Norwegian). Oslo: Pax. ISBN 82-530-1868-1.

- Dahl, Hans Fredrik (1999). Hallo - hallo! Kringkastingen i Norge 1920-1940 (in Norwegian) (2nd ed.). Oslo: Cappelen. ISBN 82-02-18478-9.

- Dahl, Hans Fredrik (1999). "Dette er London". NRK i krig 1940-1945 (in Norwegian) (2nd ed.). Oslo: Cappelen. ISBN 82-02-18577-7.

- Dahl, Hans Fredrik; Bastiansen. Henrik G. (1999). Over til Oslo. NRK som monopol 1945-1981 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Cappelen. ISBN 82-02-17644-1.

- Eide, Martin (2000). Den redigerende makt. Redaktørrollens norske historie (in Norwegian). Kristiansand: IJ-forlaget. ISBN 82-7147-205-4.

- Allern, Sigurd (2001). Flokkdyr på Løvebakken. Søkelys på Stortingets presselosje og politikkens medierammer (in Norwegian). Oslo: Pax. ISBN 82-530-2316-2.

- Allern, Sigurd (2001). Nyhetsverdier. Om markedsorientering og journalistikk i ti norske aviser (in Norwegian). Kristiansand: IJ-forlaget. ISBN 82-7147-210-0.

- Ottosen, Rune; Røssland, Lars Arve; Østbye, Helge (2002). Norsk pressehistorie (in Norwegian). Oslo: Samlaget. ISBN 82-521-5750-5.

- Eide, Elisabeth; Simonsen, Anne Hege (2008). Verden skapes hjemmefra. Pressedekningen av den ikke-vestlige verden 1902-2002 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Unipub. ISBN 978-82-7477-288-5.

- Bastiansen, Henrik; Dahl, Hans Fredrik (2008). Norsk mediehistorie (in Norwegian) (2nd ed.). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. ISBN 978-82-15-01353-4.

External links

- "Media Landscapes: Norway", Medialandscapes.org, Netherlands: European Journalism Centre