Broadnose sevengill shark

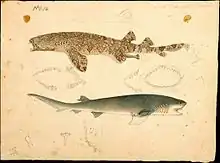

The broadnose sevengill shark (Notorynchus cepedianus) is the only extant member of the genus Notorynchus, in the family Hexanchidae. It is recognizable because of its seven gill slits, while most shark species have five gill slits, with the exception of the members of the order Hexanchiformes and the sixgill sawshark. This shark has a large, thick body, with a broad head and blunt snout. The top jaw has jagged, cusped teeth and the bottom jaw has comb-shaped teeth. Its single dorsal fin is set far back along the spine towards the caudal fin, and is behind the pelvic fins. In this shark the upper caudal fin is much longer than the lower, and is slightly notched near the tip. Like many sharks, this sevengill is counter-shaded. Its dorsal surface is silver-gray to brown in order to blend with the dark water and substrate when viewed from above. In counter to this, its ventral surface is very pale, blending with the sunlit water when viewed from below. The body and fins are covered in a scattering of small black & white spots. In juveniles, their fins often have white margins.

| Broadnose sevengill shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Broadnose sevengill shark at Aquarium of the Bay | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Hexanchiformes |

| Family: | Hexanchidae |

| Genus: | Notorynchus |

| Species: | N. cepedianus |

| Binomial name | |

| Notorynchus cepedianus (Péron, 1807) | |

| |

| Range of the broadnose sevengill shark | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Heptranchias haswelli* Ogilby, 1897

* ambiguous synonym | |

It is also known as sevengill shark or simply sevengill and was formerly known as cow shark and mud shark; it is called sevengill due to its seven gill slits. Because of this, it was listed along with the sharpnose sevengill shark (Heptranchias perlo) by Guinness World Records as having the most gill slits.[2] It is similar to the sharpnose sevengill shark but the latter has a pointed snout and lacks spots on its dorsal surface.[3][4] The sevengill species are also related to ancient sharks as fossils from the Jurassic Period (200 to 145 million years ago) also had seven gills. As recently as the 1930s and 1940s, the shark was targeted by fisheries along the coast of California and, once the commercial fishery receded, recreational fishing of the shark started in the 1980s and 1990s.[5]

Taxonomy

Name

The genus name Notorynchus a portmanteau is derived from the Ancient Greek νῶτον (nôton, meaning "back") prefixed to the Ancient Greek ῥῠ́γχος (rhúnkhos, meaning “snout”).[6] It has been interpreted that this refers to the spots on the broadnose sevengill's dorsal. The specific epithet cepedianus is derived from a variation of the name Lacepede, which refers to Bernard Germain de Lacépède, a French naturalist during the late 18th and early 19th century.[7] Altogether, the scientific name as a whole literally means "Lacepede's back snout".

The common name "broadnose sevengill shark" refers to the seven gill slits the species possesses and the shape of its snout. Sometimes, the name is shortened to "sevengill shark" or simply "sevengill". However, a variety of other common names are known in many languages. Other known common names in English include the bluntnose sevengill shark, broad-snout, cowshark, ground shark, seven-gill cowshark, seven-gilled shark, spotted cow shark, spotted seven-gill shark, and Tasmanian tiger shark. Common names from other languages include cação-bruxa (Portuguese), cañabota gata, gatita, tiburón de 7 gallas, tiburón pinto, and tollo fume (Spanish), ebisuzame and minami-ebisuzame (Japanese), gevlekte zevenkieuwshaai (Dutch), Kammzähner and Siebenkiemiger Pazifischer Kammzähner (German), koeihaai (Afrikaans), k'wet'thenéchte (Salish), platneus-sewekiefhaai (Afrikaans), platnez and requin malais (French), siedmioszpar plamisty (Polish), and tuatini (Maori).[3][5]

Description

The length at birth is 40–45 cm (15.5–17.5 in) while the mature male length is 1.5 m (4.9 ft) and mature female length is around 2.2 m (7.2 ft).[1] The maximum length found is 3 metres (9.8 ft). The maximum recorded weight is 182 kg (401 lb) for a 2.91-metre (9.5 ft) individual.[8] The shark is large and active and has a large head but small eyes and snout.[5] The mouth is broad and prominent.[9] The shark has one dorsal fin at the back of the body that spans from the insertion to the tops of the pelvic fins.[5] The mottled grey and white body is covered in a variable number of small black spots.[9]

Front part including the seven gills

Front part including the seven gills Bottom part

Bottom part Jaws

Jaws Upper teeth

Upper teeth Lower teeth

Lower teeth CT scan of the broadnose sevengill shark's braincase

CT scan of the broadnose sevengill shark's braincase

Range and habitat

The broadnose sevengill has so far been found in the western Pacific Ocean off China, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, the eastern Pacific Ocean off Canada, United States and Chile, and the southern Atlantic Ocean off Argentina and South Africa. It is significantly found in the San Francisco Bay particularly near the Golden Gate Bridge and Alcatraz Island.[10] Large, old individuals tend to live in deep offshore environments as far down as 446 feet (136 m). However, most individuals live in either the deep channels of bays, or in the shallower waters of continental shelves and estuaries. These sharks are mainly benthic in nature, cruising along the sea floor and making an occasional foray to the surface.[11] Individuals that live closer to the coast in South Africa tend to prefer more open areas with a sandy sea floor and sparse clumps of kelp.[9]

Behavior

.jpg.webp)

An opportunistic predator, the broadnose sevengill preys on a great variety of animals and has been found at a depth of 1,870 feet (570 meters) in offshore waters.[5] It has been found to feed on sharks (including gummy shark, one of its main prey,[12] and cowsharks), rays, chimaeras, cetaceans, pinnipeds, bony fishes and carrion and will also feed on whatever it finds such as shark egg cases, sea snails and remains of rats and humans. Research in 2003 found that its diet consisted of 30% mammals with a frequency of occurrence of 35%.[13] It is a frequent top predator in shallow waters[14] and has comb-like teeth,[15] with the upper teeth having slender, smooth edged cusps to swallow small enough prey whole and lower teeth broad enough to bite prey to pieces.[16] These sharks occasionally hunt in packs to take down larger prey, using tactics such as stealth to succeed.[17] After feeding, it slowly digests the food for several hours and days and can go weeks until eating again.[18] Large predatory sharks such as the great white shark can be a threat and cannibalism among this shark has also been recorded. The species have also been observed being preyed upon by Orcas in False Bay on the South African coast.[19] When not highly active, it hunts stealthily while making very little movement except for moving its caudal fin until dashing to strike.[5]

It can be one of the most abundant predators in coastal waters in summer and, in southeast Tasmania, there is a high abundance of elasmobranches including the gummy shark in coastal regions in summer. In New Zealand, it is also one of the most common inshore sharks.[20] While it is mainly a nocturnal forager, it may opportunistically feed on prey casually found during the day, however, research in 2010, found even amounts of activity during day and night. During this research, this shark was consistently detected at all depths from bottom to near surface whereas it was the substrate during the day. It also found that as Norfolk Bay does not have adequate shelter cover, this species may use group formation to avoid predation.[12]

This sevengill, like all other members of Hexanchiformes, is ovoviviparous. The broadnose sevengill lives for about 30 years[1] although the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife in Washington state lists a maximum of 49 years.[21] with the male maturing at 4 to 5 years and the female 11 to 21 years; the average reproductive age for a female is 20 to 25 years.[22] After a 12-month gestation period, the female moves to a shallow bay or estuary to give birth between April and May[23] to a large litter of between 82 and 95 pups, measuring 40–45 cm (15.5–17.5 in).

In 2004 and 2005, along with research for the sand tiger shark, there was research for the broadnose sevengill shark for development techniques for semen collection and artificial insemination to potentially increase breeding and lower overreliance on natural mating.[24] Research in 2010 found that this shark has very poorly calcified vertebrae that cannot be used for age and growth estimations.[25] Research in 2009 in Ría Deseado (RD) and Bahía San Julián (SJ), Argentina found that females were larger in RD than SJ and the heaviest female in RD was 70 kg while it was 36.9 kg in SJ. For the males, the heaviest in RD was 40 kg while it was 32.5 in SJ. Both locations also found the most significant to occur December and January.[26]

Research in 2014 also found that for the first time, reproductive hormones levels were found in the broadnose sevengill shark.[27] for a few years before venturing out. The probable predators of this species are larger sharks. Research from 2002 showed that although juvenile sevengill sharks utilize nursery areas in a similar way, males mature faster than females even if they are the same size and thus males are more likely to leave the nursery area before females.[28]

In 2004, John G Maisey of the American Museum of Natural History published a detailed analysis of the broadnose sevengill shark including imagery such as CT scans and morphology of its braincase.[29]

Conservation and relationship to humans

The broadnose sevengill is listed by the IUCN Red List as Vulnerable throughout its range. [5] This species likely suffers great ongoing pressure[1] from various types of fisheries, and from frequently being caught as bycatch. In Argentina, it's fished by rod and reel and broadnose sevengill shark fishing competitions have been occurring since the 1960s.[26] It is also threatened by water pollution and is hunted for its liveroil and hide which is considered good quality in places such as China. In the early 1980s, intense fishing in the San Francisco Bay caused a local decline. In June 2018 the New Zealand Department of Conservation classified the broadnose sevengill shark as "Not Threatened" with the qualifiers "Data Poor" and "Secure Overseas" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.[30]

Its meat and fins are in demand in countries such as the US, Brazil, Spain, Germany, Netherlands and Israel, and is packaged for frozen food.[31] The broadnose sevengill is also a source of vitamin A and utilized by South African sport anglers for winter tournaments, however, this shark is not easy to land despite being readily hooked.[4]

It is frequently seen by tourists[32] and in temperate water aquariums and can adapt to captivity.[33] One of the aquariums that houses the broadnose sevengill shark, Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport, Oregon, has featured it as a "keynote species".[34] There is also an app Sevengill Shark Tracking "Shark Observers" that allows divers to log sightings that are added to the Shark Observation Network, where the information supports "environmental awareness, assessment and policy making, and public participation at a global level".[35]

Not many conservation measures are known but it has been recorded from one marine reserve in South Africa and it occurs in La Jolla Cove, La Jolla, San Diego, California with the latter having an apparent population increase in 2013.[36] 2009 research also suggested that Bahía Anegada be made a conservation area given the high number of sharks there.[26] In Washington state, recreational fishing of broadnose sevengill shark is closed on all state waters.[21] In Victoria, Australia, the Department of Environment and Primary Industries sets a one bag limit and must be whole or in carcass form.[37]

The International Shark Attack File considers this shark to be potentially dangerous because of its proximity to humans, and because of its aggressive behavior when provoked. It has also been noted as being aggressive towards divers and spearfishermen in both public aquariums and the wild. In 2013, in Fiordland, New Zealand, a sevengill bit a diver's regulator and then her head.[5][38] Human remains were also supposedly found in one specimen's stomach. Seven attacks on humans by the broadnose sevengill have been recorded since the 16th century, with no known fatalities . In 2020 a 13 year old girl was bitten while surfing at Oreti Beach in New Zealand. The girl continued to surf for an hour before realizing her leg was bleeding.[39]

References

- Finucci, B.; Barnett, A.; Cheok, J.; Cotton, C.F.; Kulka, D.W.; Neat, F.C.; Pacoureau, N.; Rigby, C.L.; Tanaka, S.; Walker, T.I. (2020). "Notorynchus cepedianus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T39324A2896914. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T39324A2896914.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Glenday, Craig (2013). Guinness World Records 2013. Guinness World Records. p. 61. ISBN 978-0345547118.

- Castro, Jose I.; Peebles, Diane Rome (2011). "The Sharks of North America". Oxford University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0195392944.

- Van der Elst, Rudy (1993). A Guide to the Common Sea Fishes of Southern Africa. Struik. p. 55. ISBN 1868253945.

- "Sevengill shark". flmnh.ufl.edu. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- Hart, J. L. (1973). Pacific Fishes of Canada (PDF). Fisheries Research Board of Canada. p. 28.

- Ebert, David (2003). Sharks, Rays, and Chimaeras of California. University of California Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780520222656.

- Castro, Jose I. (28 July 2011). The Sharks of North America. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-19-539294-4.

- Zsilavecz, Guido (2005). Coastal fishes of the Cape Peninsula and False Bay : a divers' identification guide. Cape Town: Southern Underwater Research Group. ISBN 0-620-34230-7. OCLC 70133147.

- "Fascinating Facts About Sevengill Sharks". kqed.org. August 2, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- Compagno, Leonardo, Dando, Marc and Fowler, Sarah. (2005) Sharks of the World. Princeton University Press. pp. 67–68. ISBN 9780691120720

- Barnett, Adam; Abrantes, Kátya G.; Stevens, John D.; Bruce, Barry D.; Semmens, Jayson M. (2010). "Fine-Scale Movements of the Broadnose Sevengill Shark and Its Main Prey, the Gummy Shark". PLOS ONE. 5 (12): e15464. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...515464B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015464. PMC 2997065. PMID 21151925.

- Crespi-Abril, A. C.; García, N. A.; Crespo, E. A.; Coscarella, M. A. (2003). "Consumption of marine mammals by broadnose sevengill shark Notorynchus cepedianus in the northern and central Patagonian shelf". Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals. 2 (2). doi:10.5597/lajam00038. hdl:11336/30393. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- Castro, José Ignacio; Woodley, Christa M.; Brudek, Rebecca L. (1999). A Preliminary Evaluation of the Status of Shark Species, Issue 380. Food and Agriculture Organization. p. 9. ISBN 9251042993.

- Lubke, Roy; De Moor, Irene J. (1998). Field Guide to the Eastern and Southern Cape Coasts. Juta and Company Ltd. p. 139. ISBN 1919713034.

- Rathbone, Jim; Rathbone, LeAnn (2009). Sharks Pasta and Present. DomoAji Publications (self-published). p. 26. ISBN 978-1607029601.

- Ebert, D. A. (December 1991). "Observations on the predatory behaviour of the sevengill shark Notorynchus cepedianus". South African Journal of Marine Science. 11 (1): 455–465. doi:10.2989/025776191784287637.

- "Broadnose sevengill shark". montereybayaquarium.org. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- Qukula, Qama (5 February 2019). "Shark-eating killer whales lurking in Cape Town's waters". capetalk.co.za.

- "Summer Series 6: Broadnose Sevengill Shark". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. January 31, 2012. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- "Bottomfish – Broadnose sevengill shark". wdfw.wa.gov. Archived from the original on June 23, 2015. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- Fowler, Sarah L. (2005). Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras: The Status of the Chondrichthyan Fishes : Status Survey. IUCN. p. 224. ISBN 2831707005.

- Helfman, Gene; Burgess, George H. (2014). Sharks. Johns Hopkins University. p. 121. ISBN 978-1421413105.

- "Grey Nurse Shark Research". waza.org. Archived from the original on June 24, 2015. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- Braccini, J. M.; Troynikov, V. S.; Walker, T. I.; Mollet, H. F.; Ebert, D. A.; Barnett, A.; Kirby, N. (2010). "Incorporating heterogeneity into growth analyses of wild and captive broadnose sevengill sharks Notorynchus cepedianus". Moss Landing Marine Laboratories/California State University. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- Cedrola, Paula V.; Caille, Guillermo M.; Chiaramonte, Gustavo E.; Pettovello, Alejandro D. (2009). "Demographic structure of broadnose seven-gill shark, Notorynchus cepedianus, caught by anglers in southern Patagonia, Argentina". Marine Biodiversity Records. 2. doi:10.1017/S1755267209990558. hdl:11336/103416.

- Awruch, C. A.; Jones, S. M.; Asorey, M. G.; Barnett, A. (2014). "Non-lethal assessment of the reproductive status of broadnose sevengill sharks (Notorynchus cepedianus) to determine the significance of habitat use in coastal areas". Conservation Physiology. 2 (1): cou013. doi:10.1093/conphys/cou013. PMC 4806732. PMID 27293634.

- "Long-term trends in catch composition from elasmobranch derbies in Elkhorn Slough, California". Marine Fisheries Review. January 1, 2007. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- Maisey, John G. (February 27, 2004). "Morphology of the Braincase in the Broadnose Sevengill Shark Notorynchus (Elasmobranchii, Hexanchiformes), Based on CT Scanning" (PDF). American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- Duffy, Clinton A. J.; Francis, Malcolm; Dunn, M. R.; Finucci, Brit; Ford, Richard; Hitchmough, Rod; Rolfe, Jeremy (2018). Conservation status of New Zealand chondrichthyans (chimaeras, sharks and rays), 2016 (PDF). Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation. p. 10. ISBN 9781988514628. OCLC 1042901090.

- Vannuccini, Stefania (1999). Shark Utilization, Marketing, and Trade. Food and Agriculture Organization. p. 282. ISBN 9251043612.

- Techera, Erika J.; Klein, Natalie (2014). Sharks: Conservation, Governance and Management. Routledge. p. 242. ISBN 978-1135012618.

- Michael, Scott W. (2005). Reef Sharks and Rays of the World. ProStar Publications. p. 341577855388. ISBN 1577855388.

- "Swimming with sharks: 'You're going to be in their space'". kval.com. March 31, 2012. Archived from the original on June 18, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- "Shark Observation Network". scientificamerican.com. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- "Sharks Attracting Attention In San Diego Waters". kpbs.org. June 4, 2013. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- "Shark". depi.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- Turner, Anna (January 19, 2013). "Shark Attacks Diver in Fiordland". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 21 Apr 2020.

- Rowe, Damian (January 17, 2020). "Girl continues to surf after possible shark bite at Oreti Beach". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 21 Apr 2020.