Novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living writing novels and other fiction, while others aspire to support themselves in this way or write as an avocation. Most novelists struggle to have their debut novel published, but once published they often continue to be published, although very few become literary celebrities, thus gaining prestige or a considerable income from their work.

Description

Novelists come from a variety of backgrounds and social classes, and frequently this shapes the content of their works. Public reception of a novelist's work, the literary criticism commenting on it, and the novelists' incorporation of their own experiences into works and characters can lead to the author's personal life and identity being associated with a novel's fictional content. For this reason, the environment within which a novelist works and the reception of their novels by both the public and publishers can be influenced by their demographics or identity; important among these culturally constructed identities are gender, sexual identity, social class, race or ethnicity, nationality, religion, and an association with place. Similarly, some novelists have creative identities derived from their focus on different genres of fiction, such as crime, romance or historical novels.

While many novelists compose fiction to satisfy personal desires, novelists and commentators often ascribe a particular social responsibility or role to novel writers. Many authors use such moral imperatives to justify different approaches to novel writing, including activism or different approaches to representing reality "truthfully."

Etymology

Novelist is a term derivative from the term "novel" describing the "writer of novels." The Oxford English Dictionary recognizes other definitions of novelist, first appearing in the 16th and 17th centuries to refer to either "An innovator (in thought or belief); someone who introduces something new or who favours novelty" or "An inexperienced person; a novice."[1] However, the OED attributes the primary contemporary meaning of "a writer of novels" as first appearing in the 1633 book "East-India Colation" by C. Farewell citing the passage "It beeing a pleasant observation (at a distance) to note the order of their Coaches and Carriages..As if (presented to a Novelist) it had bin the spoyles of a Tryumph leading Captive, or a preparation to some sad Execution"[1] According to the Google Ngrams, the term novelist first appears in the Google Books database in 1521.[2]

Process, publication and profession

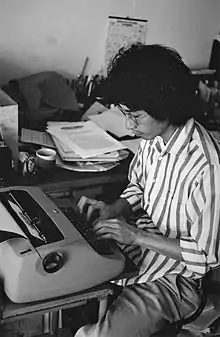

The difference between professional and amateur novelists often is the author's ability to publish. Many people take up novel writing as a hobby, but the difficulties of completing large scale fictional works of quality prevent the completion of novels. Once authors have completed a novel, they often will try to publish it. The publishing industry requires novels to have accessible profitable markets, thus many novelists will self-publish to circumvent the editorial control of publishers. Self-publishing has long been an option for writers, with vanity presses printing bound books for a fee paid by the writer. In these settings, unlike the more traditional publishing industry, activities usually reserved for a publishing house, like the distribution and promotion of the book, become the author's responsibility. The rise of the Internet and electronic books has made self publishing far less expensive and a realistic way for authors to realize income.

Novelists apply a number of different methods to writing their novels, relying on a variety of approaches to inspire creativity.[3] Some communities actively encourage amateurs to practice writing novels to develop these unique practices, that vary from author to author. For example, the internet-based group, National Novel Writing Month, encourages people to write 50,000-word novels in the month of November, to give novelists practice completing such works. In the 2010 event, over 200,000 people took part – writing a total of over 2.8 billion words.[4]

Age and experience

Novelists do not usually publish their first novels until later in life. However, many novelists begin writing at a young age. For example, Iain Banks began writing at eleven, and at sixteen completed his first novel, "The Hungarian Lift-Jet", about international arms dealers, "in pencil in a larger-than-foolscap log book".[5] However, he was thirty before he published his first novel, the highly controversial The Wasp Factory in 1984. The success of this novel enabled Banks to become a full-time novelist. Often an important writers' juvenilia, even if not published, is prized by scholars because it provides insight into an author's biography and approach to writing; for example, the Brontë family's juvenilia that depicts their imaginary world of Gondal, currently in the British Library, has provided important information on their development as writers.[6][7][8]

Occasionally, novelists publish as early as their teens. For example, Patrick O'Brian published his first novel, Caesar: The Life Story of a Panda-Leopard, at the age of 15, which brought him considerable critical attention.[9] Similarly, Barbara Newhall Follett's The House Without Windows, was accepted and published in 1927 when she was 13 by the Knopf publishing house and earned critical acclaim from the New York Times, the Saturday Review, and H. L. Mencken.[10] Occasionally, these works will achieve popular success as well. For example, though Christopher Paolini's Eragon (published at age 15) was not a great critical success, its popularity among readers placed it on the New York Times Children's Books Best Seller list for 121 weeks.[11]

First-time novelists of any age often are unable to have their works published, because of a number of reasons reflecting the inexperience of the author and the economic realities of publishers. Often authors must find advocates in the publishing industry, usually literary agents, to successfully publish their debut novels.[12] Sometimes new novelists will self-publish, because publishing houses will not risk the capital needed to market books by an unknown author to the public.[13][14]

Responding to the difficulty of successfully writing and publishing first novels, especially at a young age, there are a number of awards for young and first time novelists to highlight exceptional works from new and/or young authors (for examples see Category:Literary awards honouring young writers and Category:First book awards).

Income

In contemporary British and American publishing markets, most authors receive only a small monetary advance before publication of their debut novel; in the rare exceptions when a large print run and high volume of sales are anticipated, the advance can be larger.[15] However, once an author has established themselves in print, some authors can make steady income as long as they remain productive as writers. Additionally, many novelists, even published ones, will take on outside work, such as teaching creative writing in academic institutions, or leave novel writing as a secondary hobby.[16][17]

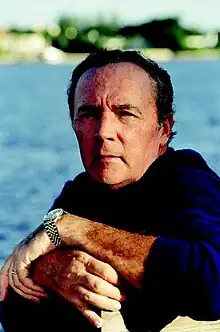

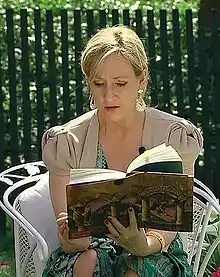

Few novelists become literary celebrities or become very wealthy from the sale of their novels alone. Often those authors who are wealthy and successful will produce extremely popular genre fiction. Examples include authors like James Patterson, who was the highest paid author in 2010, making 70 million dollars, topping both other novelists and authors of non-fiction.[18] Other famous literary millionaires include popular successes like J. K. Rowling, author of the Harry Potter series, Dan Brown author of The Da Vinci Code, historical novelist Bernard Cornwell, and Twilight author Stephenie Meyer.

Personal experience

"[the novelist's] honesty is bound to the vile stake of his megalomania [...]

The novelist is the sole master of his work. He is his work."

The personal experiences of the novelist will often shape what they write and how readers and critics will interpret their novels. Literary reception has long relied on practices of reading literature through biographical criticism, in which the author's life is presumed to have influence on the topical and thematic concerns of works.[20][21] Some veins of criticism use this information about the novelist to derive an understanding of the novelist's intentions within his work. However, postmodern literary critics often denounce such an approach; the most notable of these critiques comes from Roland Barthes who argues in his essay "Death of the Author" that the author no longer should dictate the reception and meaning derived from their work.

Other, theoretical approaches to literary criticism attempt to explore the author's unintentional influence over their work; methods like psychoanalytic theory or cultural studies, presume that the work produced by a novelist represents fundamental parts of the author's identity. Milan Kundera describes the tensions between the novelist's own identity and the work that the author produces in his essay in The New Yorker titled "What is a novelist?"; he says that the novelist's "honesty is bound to the vile stake of his megalomania [...]The work is not simply everything a novelist writes-notebooks, diaries, articles. It is the end result of long labor on an aesthetic project[...]The novelist is the sole master of his work. He is his work."[19] The close intimacy of identity with the novelist's work ensures that particular elements, whether for class, gender, sexuality, nationality, race, or place-based identity, will influence the reception of their work.

Socio-economic class

Historically, because of the amount of leisure time and education required to write novels, most novelists have come from the upper or the educated middle classes. However, working men and women began publishing novels in the twentieth century. This includes in Britain Walter Greenwood's Love on the Dole (1933), from America B. Traven's, The Death Ship (1926) and Agnes Smedley, Daughter of Earth (1929) and from the Soviet Union Nikolay Ostrovsky's How the Steel Was Tempered (1932). Later, in 1950s Britain, came a group of writers known as the "Angry young men," which included the novelists Alan Sillitoe and Kingsley Amis, who came from the working class and who wrote about working class culture.[22][23]

Some novelists deliberately write for a working class audience for political ends, profiling "the working classes and working-class life; perhaps with the intention of making propaganda".[24] Such literature, sometimes called proletarian literature, maybe associated with the political agendas of the Communist party or left wing sympathizers, and seen as a "device of revolution".[25] However, the British tradition of working class literature, unlike the Russian and American, was not especially inspired by the Communist Party, but had its roots in the Chartist movement, and socialism, amongst others.[26]

National or place-based identity

Novelists are often classified by their national affiliation, suggesting that novels take on a particular character based on the national identity of the authors. In some literature, national identity shapes the self-definition of many novelists. For example, in American literature, many novelists set out to create the "Great American Novel", or a novel that defines the American experience in their time. Other novelists engage politically or socially with the identity of other members of their nationality, and thus help define that national identity. For instance, critic Nicola Minott-Ahl describes Victor Hugo's Notre-Dame de Paris directly helping in the creation of French political and social identity in mid-nineteenth century France.[27]

Some novelists become intimately linked with a particular place or geographic region and therefore receive a place-based identity. In his discussion of the history of the association of particular novelists with place in British literature, critic D. C. D. Pocock, described the sense of place not developing in that canon until a century after the novel form first solidified at the beginning of the 19th century.[28] Often such British regional literature captures the social and local character of a particular region in Britain, focussing on specific features, such as dialect, customs, history, and landscape (also called local colour): "Such a locale is likely to be rural and/or provincial."[29] Thomas Hardy's (1840-1928) novels can be described as regional because of the way he makes use of these elements in relation to a part of the West of England, that he names Wessex. Other British writers that have been characterized as regional novelists, are the Brontë sisters, and writers like Mary Webb (1881-1927), Margiad Evans (1909–58) and Geraint Goodwin (1903–42), who are associate with the Welsh border region. George Eliot (1801–86) on the other hand is particularly associated with the rural English Midlands, whereas Arnold Bennett (1867–1931) is the novelist of the Potteries in Staffordshire, or the "Five Towns", (actually six) that now make-up Stoke-on-Trent. Similarly, novelist and poet Walter Scott's (1771-1832) contribution in creating a unified identity for Scotland and were some of the most popular in all of Europe during the subsequent century. Scott's novels were influential in recreating a Scottish identity that the upper-class British society could embrace.

In American fiction, the concept of American literary regionalism ensures that many genres of novel associated with particular regions often define the reception of the novelists. For example, in writing Western novels, Zane Grey has been described as a "place-defining novelist", credited for defining the western frontier in America consciousness at the beginning of the 20th century while becoming linked as an individual to his depiction of that space.[30]

Similarly, novelist such as Mark Twain, William Faulkner, Eudora Welty, and Flannery O'Connor are often describe as writing within a particular tradition of Southern literature, in which subject matter relevant to the South is associated with their own identities as authors. For example, William Faulkner set many of his short stories and novels in Yoknapatawpha County,[31] which is based on, and nearly geographically identical to, Lafayette County, of which his hometown of Oxford, Mississippi.[32] In addition to the geographical component of Southern literature, certain themes have appeared because of the similar histories of the Southern states in regard to slavery, the American Civil War, and Reconstruction. The conservative culture in the South has also produced a strong focus by novelists from there on the significance of family, religion, community, the use of the Southern dialect, along with a strong sense of place.[33] The South's troubled history with racial issues has also continually concerned its novelists.[34]

In Latin America a literary movement called Criollismo or costumbrismo was active from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century, which is considered equivalent to American literary regionalism. It used a realist style to portray the scenes, language, customs and manners of the country the writer was from, especially the lower and peasant classes, criollismo led to an original literature based on the continent's natural elements, mostly epic and foundational. It was strongly influenced by the wars of independence from Spain and also denotes how each country in its own way defines criollo, which in Latin America refers to locally-born people of Spanish ancestry.[35]

Gender and sexuality

Novelists often will be assessed in contemporary criticism based on their gender or treatment of gender. Largely, this has to do with the impacts of cultural expectations of gender on the literary market, readership and authorship.[36][37] Literary criticism, especially since the rise of feminist theory, pays attention to how women, historically, have experienced a very different set of writing expectations based on their gender; for example, the editors of The Feminist Companion to Literature in English point out: "Their texts emerge from and intervene in conditions usually very different from those which produced most writing by men."[37] It is not a question of the subject matter or political stance of a particular author, but of her gender: her position as a woman within the literary marketplace. However, the publishing market's orientation to favor the primary reading audience of women may increasingly skew the market towards female novelists; for this reason, novelist Teddy Wayne argued in a 2012 Salon article titled "The agony of the male novelist" that midlist male novelists are less likely to find success than midlist female novelist, even though men tend to dominate "literary fiction" spaces.[17]

The position of women in the literary marketplace can change public conversation about novelists and their place within popular culture, leading to debates over sexism. For example, in 2013, American female novelist Amanda Filipacchi wrote a New York Times editorial challenging Wikipedia's categorization of American female novelists within a distinct category, which precipitated a significant amount of press coverage describing that Wikipedia's approach to categorization as sexism. For her, the public representation of women novelists within another category marginalizes and defines women novelists like herself outside of a field of "American novelists" dominated by men.[38] However, other commentators, discussing the controversy also note that by removing such categories as "Women novelist" or "Lesbian writer" from the description of gendered or sexual minorities, the discover-ability of those authors plummet for other people who share that identity.[39]

Similarly, because of the conversations brought by feminism, examinations of masculine subjects and an author's performance of "maleness" are a new and increasingly prominent approach critical studies of novels.[40][41] For example, some academics studying Victorian fiction spend considerable time examining how masculinity shapes and effects the works, because of its prominence within fiction from the Victorian period.[42]

Genre

Traditionally, the publishing industry has distinguished between "literary fiction", works lauded as achieving greater literary merit, and "genre fiction", novels written within the expectations of genres and published as consumer products.[43] Thus, many novelists become slotted as writers of one or the other.[43] Novelist Kim Wright, however, notes that both publishers and traditional literary novelist are turning towards genre fiction because of their potential for financial success and their increasingly positive reception amongst critics.[43] Wright gives examples of authors like Justin Cronin, Tom Perrotta and Colson Whitehead all making that transition.[43]

However, publishing genre novels does not always allow novelist to continue writing outside the genre or within their own interests. In describing the place within the industry, novelist Kim Wright says that many authors, especially authors who usually write literary fiction, worry about "the danger that genre is a cul-de-sac" where publishers will only publish similar genre fiction from that author because of reader expectations, "and that once a writer turns into it, he'll never get out."[43] Similarly, very few authors start in genre fiction and move to more "literary" publications; Wright describes novelists like Stephen King as the exception rather than the norm.[43] Other critics and writers defending the merits of genre fiction often point towards King as an example of bridging the gap between popular genres and literary merit.[44][45]

Role and objective

Both literary critics and novelists question what role novelists play in society and within art. For example, Eudora Welty writing in 1965 for in her essay "Must the Novelist Crusade?" draws a distinction between novelists who report reality by "taking life as it already exists, not to report it, but to make an object, toward the end that the finished work might contain this life inside it, and offer it to the reader" and journalists, whose role is to act as "crusaders" advocating for particular positions, and using their craft as a political tool.[46] Similarly, writing in the 1950s, Ralph Ellison in his essay "Society, Morality, and the Novel", sees the novelist as needing to "re-create reality in the forms which his personal vision assumes as it plays and struggles with the vivid illusory "eidetic-like" imagery left in the mind's eye by the process of social change."[47] However, Ellison also describes novelists of the Lost Generation, like Ernest Hemingway, not taking full advantage of the moral weight and influence available to novelists, pointing to Mark Twain and Herman Melville as better examples.[47] A number of such essays, such as literary critic Frank Norris's "Responsibilities of a Novelist", highlight such moral and ethical justifications for their approach to both writing novels and criticizing them.[48]

When defining her description of the role of the modernist novelist in the essay "Modern Fiction", Virginia Woolf argues for a representation of life not interested in the exhaustive specific details represented in realism in favor of representing a "myriad of impressions" created in experience life.[49] Her definition made in this essay, and developed in others, helped define the literary movement of modernist literature. She argues that the novelist should represent "not a series of gig-lamps symmetrically arranged; [rather] life is luminous halo, a semitransparent envelope surrounding us from the beginning of the conscious to the end. Is it not the task of the novelist to convey this varying, this unknown and uncircumscribed spirit, whatever aberration or complexity it may display, with as little mixture of the alien and external as possible?"[49]

See also

- Author

- Category:Novelists, a category containing all Wikipedia articles about novelists

- Imagination

- List of novelists by genre

- List of novelists by nationality

- Narrative

- Storytelling

References

- "novelist, n." OED Online. Oxford University Press. December 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- "Google Ngrams "Novelist" 1680-2014". Retrieved February 11, 2014.

- Alter, Alexandra (2009-11-13). "How to Write a Great Novel". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- Grant, Lindsey (December 1, 2010). "The Office of Letters and Light Blog – The Great NaNoWriMo Stats Party". Blog.lettersandlight.org. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- "Doing the Business: Iain Banks", The Guardian, Saturday 7 August 1999.

- Bernard, Robert; Bernard, Louise, eds. (2007). A Brontë Encyclopedia. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 126–127. ISBN 9780470765784.

- Brontë, Emily Jane (1938). Helen Brown and Joan Mott (ed.). Gondal Poems. Oxford: The Shakespeare Head Press. pp. 5–8.

- The Brontës' secret science fiction stories, British Library, 11 May 2011

- King, Dean (2000). Patrick O'Brian:A life revealed. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 50. ISBN 0-340-79255-8.

- Paul Collins (December 2010). "Vanishing Act". Lapham's Quarterly. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- "New York Times Best Seller List". The New York Times. 2008-01-06.

- Woodroof, Martha (October 8, 2013). "First Novels: The Romance Of Agents". Monkey See. NPR. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- "The Big Question: What should you do if you want to get your first novel published? - Features, Books". The Independent. 2008-01-04. Archived from the original on June 6, 2008. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- Kapur, Niraj (26 January 2007). "How to sell your debut novel | Books | guardian.co.uk". The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- Kellaway, Kate (25 March 2007). "Kate Kellaway: That difficult first novel | Books |". The Observer. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- St. John Mandel, Emily (October 6, 2009). "Working the Double Shift". The Millions. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- Wayne, Teddy (Jan 18, 2012). "The agony of the male novelist". Salon. Retrieved 2014-02-19.

- Smillie, Dirk (2010-08-19). "The Highest-Paid Authors". Forbes.

- Kundera, Milan (October 9, 2006). "What is a Novelist?". The New Yorker (Life and Letters Section) - Subscriber Only. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- "Biographical Criticism", Writing essays about literature: a guide and style sheet (2004), Kelley Griffith, University of North Carolina at Greensborough, Wadsworth Publishing Company, pages 177-178, 400

- Benson, Jackson J. (1989) "Steinbeck: A Defense of Biographical Criticism" College Literature 16(29): pp. 107-116, page 108

- Bruce Weber (26 April 2010). "Alan Sillitoe, 'Angry' British Author, Dies at 82". New York Times. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- "Sir Kingsley Amis". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 19 October 2013. Retrieved 5 Feb 2014.

- J. A. Cuddon; A Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Criticism. (London: Penguin Books, 1999) p. 703.

- Encyclopædia Britannica."Novel." Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 13 Apr. 2013.<https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/421071/novel>.

- Ian Hayward, Working-Class Fiction: from Chartism to Trainspotting. (London: Northcote House, 1997), pp. 1-3

- Minott-Ahl, Nicola (2012). "Nation/Building: Hugo's Notre-Dame de Paris; and the Novelist as Post-Revolutionary Historian". Partial Answers: Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas. 10 (2): 251–271. doi:10.1353/pan.2012.0024. S2CID 145170286.

- Pocock, D. C. D. (1981-01-01). "Place and the Novelist". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 6 (3): 337–347. doi:10.2307/622292. ISSN 0020-2754. JSTOR 622292.

- J.A Cuddon, A Dictionary of Literary Terms. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984, p.560.

- Blake, Kevin S. (April 1995). "Zane Grey and Images of the American West". Geographical Review. 85 (2): 202–216. doi:10.2307/216063. hdl:2097/4213. JSTOR 216063.

- The Nobel Prize in Literature 1949: Biography Nobelprize.org.

- The Oxford Companion to English Literature, ed. Margaret Drabble. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996, p.346.

- Kate Cochran, review of Remapping Southern Literature: Contemporary Southern Writers and the West by Robert H. Brinkmeyer. College Literature Vol. 29, No. 2 (Spring, 2002), pp. 169-171.

- Fred Hobson. But Now I See: The White Southern Racial Conversion Narrative, Louisiana State University Press, 1999.

- Criollismo www.memoriachilena.cl Dirección de Bibliotecas, Archivos y Museos Copyright 2013© MEMORIA CHILENA ®. Todos los Derechos Reservados May 16, 2009 Retrieved September 04, 2013 (in Spanish)

- Murfin, Ross C.; Smith, Johanna M. (1996), Murfin, Ross C. (ed.), "Feminist and Gender Criticism and Heart of Darkness", Heart of Darkness: Joseph Conrad, Case Studies in Contemporary Criticism, London: Macmillan Education UK, pp. 148–184, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-14016-9_5, ISBN 978-1-349-14016-9, retrieved 2021-10-07

- Blain, Virginia; Isobel Grundy; Patricia Clements, eds. (1990). The Feminist Companion to Literature in English. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. viii–ix. ISBN 9780300048544.

- Neary, Lynn (April 29, 2013). "What's In A Category? 'Women Novelists' Sparks Wiki-Controversy". NPR.

- S.E. Smith (April 26, 2013). "Is Wikipedia's "American Women Novelists" Category Horribly Sexist? Some people seem to thinks so". XO Jane. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- Mallett, Phillip, ed. (2015). The Victorian Novel and Masculinity. doi:10.1057/9781137491541. ISBN 978-1-349-32313-5.

- Hobbs, Alex (2013). "Masculinity Studies and Literature". Literature Compass. 10 (4): 383–395. doi:10.1111/lic3.12057. ISSN 1741-4113.

- Dowling, Andrew (2001). Manliness and the Male Novelist in Victorian Literature. Ashgate Press. ISBN 9780754603801.

- Wright, Kim (September 2, 2011). "Why Are So Many Literary Writers Shifting into Genre?". The Millions. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- Nelson, Erik (7 July 2012). "Stephen King: You can be popular and good". Salon. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- Jacobs, Alan (24 July 2012). "A Defense of Stephen King, Master of the Decisive Moment". The Atlantic. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- Welty, Eudora (1965) [1965]. "Must the Novelist Crusade?". PBS. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- Ellison, Ralph (2003) [1957]. "Society, Morality and the Novel"". In John F. Callahan (ed.). The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison. The Modern Library. pp. 698–729.

- Davies, Jude (20 October 2001). "The Responsibilities of the Novelist". The Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- Woolf, Virginia (2004-06-01). "Modern Fiction" (text). The Common Reader. EBooks @ Adelaide. Retrieved 2014-03-26.

Works cited

- Kundera, Milan (October 9, 2006). "What is a Novelist?". The New Yorker (Life and Letters Section): 40.

- O'Conner, Flannery. "Novelist and Believer". CatholicCulture.org.