Korach (parashah)

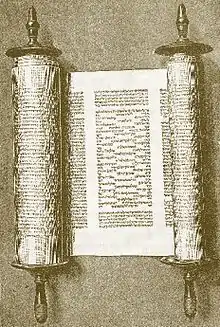

Korach or Korah (Hebrew: קֹרַח Qoraḥ—the name "Korah," which in turn means baldness, ice, hail, or frost, the second word, and the first distinctive word, in the parashah) is the 38th weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the fifth in the Book of Numbers. It tells of Korach's failed attempt to overthrow Moses.

It comprises Numbers 16:1–18:32. The parashah is made up of 5,325 Hebrew letters, 1,409 Hebrew words, 95 verses, and 184 lines in a Torah Scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1] Korach is generally read in June or July.[2]

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot.[3]

First reading—Numbers 16:1–13

In the first reading, the Levite Korah son of Izhar joined with the Reubenites Dathan and Abiram, sons of Eliab, and On, son of Peleth and 250 chieftains of the Israelite community to rise up against Moses.[4] Korah and his band asked Moses and Aaron why they placed themselves above the rest of the community, for the entire congregation is holy.[5] Moses told Korah and his band to take their fire pans and put fire and incense on them before God.[6] Moses sent for Dathan and Abiram, but they refused to come.[7]

Second reading—Numbers 16:14–19

In the second reading, the next day, Korah and his band took their fire pans and gathered the whole community against Moses and Aaron at the entrance of the Tabernacle.[8]

Third reading—Numbers 16:20–17:8

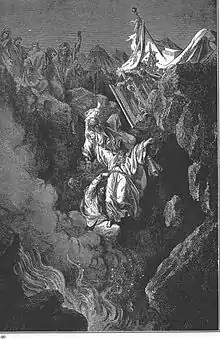

In the third reading, the Presence of the Lord appeared to the whole community, and God told Moses and Aaron to stand back so that God could annihilate the others.[9] Moses and Aaron fell on their faces and implored God not to punish the whole community.[10] God told Moses to instruct the community to move away from the tents of Korah, Dathan, and Abiram, and they did so, while Dathan, Abiram, and their families stood at the entrance of their tents.[11] Moses told the Israelites that if these men were to die of natural causes, then God did not send Moses, but if God caused the earth to swallow them up, then these men had spurned God.[12] Just as Moses finished speaking, the earth opened and swallowed them, their households, and all Korah's people, and the Israelites fled in terror.[13] And a fire consumed the 250 men offering the incense.[14] God told Moses to order Eleazar the priest to remove the fire pans—as they had become sacred—and have them made into plating for the altar to remind the Israelites that no one other than Aaron's offspring should presume to offer incense to God.[15] The next day, the whole Israelite community railed against Moses and Aaron for bringing death upon God's people.[16] A cloud covered the Tabernacle and the God's Presence appeared.[17]

Fourth reading—Numbers 17:9–15

In the fourth reading, God told Moses to remove himself and Aaron from the community, so that God might annihilate them, and they fell on their faces.[18] Moses told Aaron to take the fire pan, put fire from the altar and incense on it, and take it to the community to make expiation for them and to stop a plague that had begun, and Aaron did so.[19] Aaron stood between the dead and the living and halted the plague, but not before 14,700 had died.[20]

Fifth reading—Numbers 17:16–24

In the fifth reading, God told Moses to collect a staff from the chieftain of each of the 12 tribes, inscribe each man's name on his staff, inscribe Aaron's name on the staff of Levi, and deposit the staffs in the Tent of Meeting.[21] The next day, Moses entered the Tent and Aaron's staff had sprouted, blossomed, and borne almonds.[22]

Sixth reading—Numbers 17:25–18:20

In the sixth reading, God instructed Moses to put Aaron's staff before the Ark of the Covenant to be kept as a lesson to rebels to end their mutterings against God.[23] But the Israelites cried to Moses, "We are doomed to perish!"[24] God spoke to Aaron and said that he and his dynasty would be responsible for the Tent of Meeting and the priesthood and accountable for anything which went wrong in the performance of their priestly duties.[25] God assigned the Levites to Aaron to aid in the performance of these duties.[26] God prohibited any outsider from intruding on the priests as they discharged the duties connected with the Shrine, on pain of death.[27] And God gave Aaron and the priests all the sacred donations and firstfruits as a perquisite for all time for them and their families to eat.[28] God gave them olive oil, wine, grain.[29] The priestly covenant was described as a "covenant of salt",[30] but God also told Aaron that the priests would have no territorial share among the Israelites, as God was their portion and their share.[31]

Seventh reading—Numbers 18:21–32

In the seventh reading, God gave the Levites all the tithes in Israel as their share in return for the services of the Tent of Meeting, but they too would have no territorial share among the Israelites.[32] God told Moses to instruct the Levites to set aside one-tenth of the tithes they received as a gift to God.[33]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jewish people who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[34]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023, 2026, 2029 . . . | 2024, 2027, 2030 . . . | 2025, 2028, 2031 . . . | |

| Reading | 16:1–17:15 | 16:20–17:24 | 17:25–18:32 |

| 1 | 16:1–3 | 16:20–27 | 17:25–18:7 |

| 2 | 16:4–7 | 16:28–35 | 18:8–10 |

| 3 | 16:8–13 | 17:1–5 | 18:11–13 |

| 4 | 16:14–19 | 17:6–8 | 18:14–20 |

| 5 | 16:20–35 | 17:9–15 | 18:21–24 |

| 6 | 17:1–8 | 17:16–20 | 18:25–29 |

| 7 | 17:9–15 | 17:21–24 | 18:30–32 |

| Maftir | 17:9–15 | 17:21–24 | 18:30–32 |

In inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[35]

Numbers chapter 16

In Numbers 16:22, Moses interceded on behalf of the community, as Abraham had in Genesis 18:23, when Abraham asked God whether God would "sweep away the righteous with the wicked." Similarly, in Numbers 16:22, Moses raised the question of collective responsibility: If one person sins, will God punish the entire community? And similarly, in 2 Samuel 24:17 and 1 Chronicles 21:17, David asked why God punished all the people with pestilence. Ezekiel 18:4 and 20 answer that God will punish only the individual who sins, and Ezekiel 18:30 affirms that God will judge every person according to that person's acts.

Numbers chapter 18

In Numbers 18:1 and 18:8, God spoke directly to Aaron, whereas more frequently in the Torah, God spoke "to Moses" or "to Moses and Aaron."[36]

1 Samuel 2:12–17 describes how (out of greed) priests who were descended from Eli sent their servants to collect uncooked meat from the people, instead of taking their entitlement in accordance with Numbers 18:8–18.

The description of the Aaronic covenant as a "covenant of salt" in Numbers 18:19 is mirrored by the description in 2 Chronicles 13:5 of God's covenant with the Davidic kings of Israel as a "covenant of salt."

Tithes, which are addressed in Numbers 18:21–24, are also addressed in Leviticus 27:30–33, and Deuteronomy 14:22–29 and 26:12–14.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[37]

Numbers chapter 16

The 1st or 2nd century CE author Pseudo-Philo read the commandment to wear blue tassels, or tzitzit, in Numbers 15:37–40 together with the story of Korah's rebellion that follows immediately after in Numbers 16:1–3. Pseudo-Philo reported that God commanded Moses about the tassels, and then Korah and the 200 men with him rebelled, asking why that unbearable law had been imposed on them.[38]

The first-century Roman-Jewish scholar Josephus wrote that Korah was an Israelite of principal account, both by family and wealth, who was able to speak well and could easily persuade the people. Korah envied the great dignity of Moses, as he was of the same tribe as Moses and he thought he better deserved honor on account of his great riches.[39]

Josephus wrote that Moses called on God to punish those who had endeavored to deal unjustly with the people, but to save the multitude who followed God's commandments, for God knew that it would not be just that the whole body of the Israelites should suffer punishment for the wickedness of the unjust.[40]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[41]

Numbers chapter 16

Like Pseudo-Philo (see "In early nonrabbinic interpretation" above), the Jerusalem Talmud read the commandment to wear tzitzit in Numbers 15:37–40 together with the story of Korah's rebellion that follows immediately after in Numbers 16:1–3. The Jerusalem Talmud told that after hearing the law of tassels, Korah made some garments that were completely dyed blue, went to Moses, and asked Moses whether a garment that was already completely blue nonetheless had to have a blue corner tassel. When Moses answered that it did, Korah said that the Torah was not of Divine origin, Moses was not a prophet, and Aaron was not a high priest.[42]

A Midrash taught that Numbers 16:1 traces Korah's descent back only to Levi, not to Jacob, because Jacob said of the descendants of Simeon and Levi in Genesis 49:5, “To their assembly let my glory not be united,” referring to when they would assemble against Moses in Korah's band.[43]

A Midrash taught that Korah, Dathan, Abiram, and On all fell in together in their conspiracy, as described in Numbers 16:1, because they lived near each other on the same side of the camp. The Midrash thus taught that the saying, "Woe to the wicked and woe to his neighbor!" applies to Dathan and Abiram. Numbers 3:29 reports that the descendants of Kohath, among whom Korah was numbered, lived on the south side of the Tabernacle. And Numbers 2:10 reports that the descendants of Reuben, among whom Dathan and Abiram were numbered, lived close by, as they also lived on the south side of the Tabernacle.[44] Similarly, a Midrash taught that because Reuben, Simeon, and Gad were close to Korah, they were all quarrelsome men; and the sons of Gad and the sons of Simeon were also contentious people.[45]

| Levi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kohath | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amram | Izhar | Hebron | Uzziel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miriam | Aaron | Moses | Korah | Nepheg | Zichri | Mishael | Elzaphan | Sithri | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Reading the words of Numbers 16:1, "And Korah took," a Midrash asked what caused Korah to oppose Moses. The Midrash answered that Korah took issue with Moses because Moses had (as Numbers 3:30 reports) appointed Elizaphan the son of Uzziel as prince of the Kohathites, and Korah was (as Exodus 6:21 reports) son of Uzziel's older brother Izhar, and thus had a claim to leadership prior to Elizaphan. Because Moses appointed the son of Korah's father's youngest brother, Uzziel, the leader, to be greater than Korah, Korah decided to oppose Moses and nullify everything that he did.[46]

Resh Lakish interpreted the words "Korah . . . took" in Numbers 16:1 to teach that Korah took a bad bargain for himself. As the three Hebrew consonants that spell Korah's name also spell the Hebrew word for "bald" (kereach), the Gemara deduced that he was called Korah because he caused a bald spot to be formed among the Israelites when the earth swallowed his followers. As the name Izhar (יִצְהָר) in Numbers 16:1 derived from the same Hebrew root as the word "noon" (צָּהֳרָיִם, tzohorayim), the Gemara deduced from "son of Izhar" that Korah was a son who brought upon himself anger hot as the noon sun. As the name Kohath (קְהָת) in Numbers 16:1 derived from the same Hebrew root as the word for "set on edge" (קהה, kihah), the Gemara deduced from "son of Kohath" that Korah was a son who set his ancestors' teeth on edge. The Gemara deduced from the words "son of Levi" in Numbers 16:1 that Korah was a son who was escorted to Gehenna. The Gemara asked why Numbers 16:1 did not say "the son of Jacob," and Rabbi Samuel bar Isaac answered that Jacob had prayed not to be listed amongst Korah's ancestors in Genesis 49:6, where it is written, "Let my soul not come into their council; unto their assembly let my glory not be united." "Let my soul not come into their council" referred to the spies, and "unto their assembly let my glory not be united" referred to Korah's assembly. As the name Dathan (דָתָן) in Numbers 16:1 derived from the same Hebrew root as the word "law" (דָּת, dat), the Gemara deduced from Dathan's name that he violated God's law. The Gemara related the name Abiram (אֲבִירָם) in Numbers 16:1 to the Hebrew word for "strengthened" (iber) and deduced from Abiram's name that he stoutly refused to repent. The Gemara related the name On (אוֹן) in Numbers 16:1 to the Hebrew word for "mourning" (אנינה, aninah) and deduced from On's name that he sat in lamentations. The Gemara related the name Peleth (פֶּלֶת) in Numbers 16:1 to the Hebrew word for "miracles" (pelaot) and deduced from Peleth's name that God performed wonders for him. And as the name Reuben (רְאוּבֵן) derived from the Hebrew words "see" (reu) and "understand" (מבין, mavin), the Gemara deduced from the reference to On as a "son of Reuben" in Numbers 16:1that On was a son who saw and understood.[47]

Rabbi Joshua identified Dathan as the Israelite who asked Moses in Exodus 2:14, "Who made you a ruler and a judge over us?"[48]

Numbers 16:1–2 reports that the Reubenite On son of Peleth joined Korah's conspiracy, but the text does not mention On again. Rav explained that On's wife saved him, arguing to him that no matter whether Moses or Korah prevailed, On would remain just a disciple. On replied that he had sworn to participate. So On's wife got him drunk with wine, and laid him down in their tent. Then she sat at the entrance of their tent and loosened her hair, so that whoever came to summon him saw her and retreated at the sight of her immodestly loosened hair. The Gemara taught that Proverbs 14:1 refers to On's wife when it says: "Every wise woman builds her house."[49]

The Mishnah in Pirkei Avot deduced that the controversy of Korah and his followers was not for the sake of Heaven, and thus was destined not to result in permanent change. The Mishnah contrasted Korah's argument to those between Hillel and Shammai, which the Mishnah taught were controversies for the sake of Heaven, destined to result in something permanent.[50]

Reading Numbers 4:18, “Cut not off the tribe of the families of the Kohathites from among the Levites,” Rabbi Abba bar Aibu noted that it would have been enough for the text to mention the family of Kohath, and asked why Numbers 4:18 also mentions the whole tribe. Rabbi Abba bar Aibu explained that God (in the words of Isaiah 46:10), “declar[es] the end from the beginning,” and provides beforehand for things that have not yet occurred. God foresaw that Korah, who would descend from the families of Kohath, would oppose Moses (as reported in Numbers 16:1–3) and that Moses would beseech God that the earth should swallow them up (as reflected in Numbers 16:28–30). So God told Moses to note that it was (in the words of Numbers 17:5) “to be a memorial to the children of Israel, to the end that no common man . . . draw near to burn incense . . . as the Lord spoke to him by the hand of Moses.” The Midrash asked why then Numbers 17:5 adds the potentially superfluous words “to him,” and replied that it is to teach that God told Moses that God would listen to his prayer concerning Korah but not concerning the whole tribe. Therefore, Numbers 4:18 says, “Cut not off the tribe of the families of the Kohathites from among the Levites.”[51]

Rabbi Simeon bar Abba in the name of Rabbi Joḥanan taught that every time Scripture uses the expression “and it was” (vayehi), it intimates the coming of either trouble or joy. If it intimates trouble, there is no trouble to compare with it, and if it itimatres joy, there is no joy to compare with it. Rabbi Samuel bar Nahman made a distinction: In every instance where Scripture employs “and it was” (vayehi), it introduces trouble, while when Scripture employs “and it shall be” (ve-hayah), it introduces joy. The Sages raised an objection to Rabbi Samuel's view, noting that to introduce the offerings of the princes, Numbers 7:12 says, “And he that presented his offering . . . was (vayehi),” and surely that was a positive thing. Rabbi Samuel replied that the occasion of the princes’ gifts did not indicate joy, because it was manifest to God that the princes would join with Korah in his dispute (as reported in Numbers 16:1–3). Rabbi Judah ben Rabbi Simon said in the name of Rabbi Levi ben Parta that the case could be compared to that of a member of the palace who committed a theft in the bathhouse, and the attendant, while afraid of disclosing his name, nevertheless made him known by describing him as a certain young man dressed in white. Similarly, although Numbers 16:1–3 does not explicitly mention the names of the princes who sided with Korah in his dispute, Numbers 16:2 nevertheless refers to them when it says, “They were princes of the congregation, the elect men of the assembly, men of renown,” and this recalls Numbers 1:16, “These were the elect of the congregation, the princes of the tribes of their fathers . . . ,” where the text lists their names. They were the “men of renown” whose names were mentioned in connection with the standards; as Numbers 1:5–15 says, “These are the names of the men who shall stand with you, of Reuben, Elizur the son of Shedeur; of Simeon, Shelumiel the son of Zurishaddai . . . .”[52]

It was taught in a Baraita that King Ptolemy brought together 72 elders and placed them in 72 separate rooms, without telling them why he had brought them together, and asked each of them to translate the Torah. God then prompted each of them to conceive the same idea and write a number of cases in which the translation did not follow the Masoretic Text, including reading Numbers 16:15 to say, "I have taken not one valuable of theirs" (substituting "valuable" for "donkey" to prevent the impression that Moses may have taken any other items).[53]

Rabbi Levi taught that God told Moses "enough!" in Deuteronomy 3:26 to repay Moses measure for measure for when Moses told Korah "enough!" in Numbers 16:3.[54]

Rava read Numbers 16:12 and 16:16 to teach requirements for judicial procedure. Rava deduced from Numbers 16:12 that a court must send an agent to summon a defendant to appear before the court before the community can ostracize the defendant. And Rava deduced from Numbers 16:16 that the court summons the defendant, the summons must set a date for the appearance, and the defendant must personally appear before the court.[55]

Noting Moses' displeasure in Numbers 16:15 with Dathan and Abiram for their failure to meet with him, the Midrash Tanḥuma compared this to a person who argues with a companion and reasons with the companion. When the companion answers, the person has peace of mind; but if the companion does not answer, then this causes the person great annoyance.[56]

Reading Numbers 16:20, a Midrash taught that in 18 verses, Scripture places Moses and Aaron (the instruments of Israel's deliverance) on an equal footing (reporting that God spoke to both of them alike),[57] and thus there are 18 benedictions in the Amidah.[58]

Rav Adda bar Abahah taught that a person praying alone does not say the Sanctification (Kedushah) prayer (which includes the words from Isaiah 6:3: (קָדוֹשׁ קָדוֹשׁ קָדוֹשׁ יְהוָה צְבָאוֹת; מְלֹא כָל-הָאָרֶץ, כְּבוֹדוֹ, Kadosh, Kadosh, Kadosh, Adonai Tz'vaot melo kol haaretz kevodo, "Holy, Holy, Holy, the Lord of Hosts, the entire world is filled with God's Glory"), because Leviticus 22:32 says: "I will be hallowed among the children of Israel," and thus sanctification requires ten people (a minyan). Rabinai the brother of Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba taught that we derive this by drawing an analogy between the two occurrences of the word "among" (תּוֹךְ, toch) in Leviticus 22:32 ("I will be hallowed among the children of Israel") and in Numbers 16:21, in which God tells Moses and Aaron: "Separate yourselves from among this congregation," referring to Korah and his followers. Just as Numbers 16:21, which refers to a congregation, implies a number of at least ten, so Leviticus 22:32 implies at least ten.[59]

Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai compared the words of Numbers 16:22, "Shall one man sin, and will You be wrathful with all the congregation?" to the case of men on a ship, one of whom took a borer and began boring beneath his own place. His shipmates asked him what he was doing. He replied that what he was doing would not matter to them, as he was boring under his own place. And they replied that the water would come up and flood the ship for them all.[60]

Reading Song of Songs 6:11, "I went down into the garden of nuts," to apply to Israel, a Midrash taught that just as when one takes a nut from a stack of nuts, all the rest come toppling over, so if a single Jewish person is smitten, all Jewish people feel it, as Numbers 16:22 says, "Shall one man sin, and will You be angry with all the congregation?"[61]

A Midrash expanded on the plea of Moses and Aaron to God in Numbers 16:22 and God's reply in Numbers 16:24. The Midrash taught that Moses told God that a mortal king who is confronted with an uprising in a province of his kingdom would send his legions to kill all the inhabitants of the province—both innocent and the guilty—because the king would not know who rebelled and who did not. But God knows the hearts and thoughts of each and every person, knows who sinned and who did not, and knows who rebelled and who did not. That is why Moses and Aaron asked God in Numbers 16:22, "Shall one man sin, and will You be wrath with all the congregation?" The Midrash taught that God replied that they had spoken well, and God would make known who had sinned and who had not.[62]

Rabbi Berekiah read Numbers 16:27 to teach how inexorably destructive dispute is. For the Heavenly Court usually does not impose a penalty until a sinner reaches the age of 20. But in Korah's dispute, even one-day-old babies were consumed by the fire and swallowed up by the earth. For Numbers 16:27 says, "with their wives, and their sons, and their little ones."[63]

The Mishnah in Pirkei Avot taught that the opening of the earth's mouth in Numbers 16:32 was one of ten miracles that God created at the end of the first week of creation at the eve of the first Sabbath at twilight.[64]

Rabbi Akiva interpreted Numbers 16:33 to teach that Korah's assembly will have no portion in the World To Come, as the words "the earth closed upon them" reported that they died in this world, and the words "they perished from among the assembly" implied that they died in the next world, as well. But Rabbi Eliezer disagreed, reading 1 Samuel 2:6 to speak of Korah's assembly when it said: "The Lord kills, and makes alive; He brings down to the grave, and brings up." The Gemara cited a Tanna who concurred with Rabbi Eliezer's position: Rabbi Judah ben Bathyra likened Korah's assembly to a lost article, which one seeks, as Psalm 119:176 said: "I have gone astray like a lost sheep; seek Your servant."[65]

The Avot of Rabbi Natan read the listing of places in Deuteronomy 1:1 to allude to how God tested the Israelites with ten trials in the Wilderness—including Koraḥ's rebellion—and they failed them all. The words "In the wilderness" alludes to the Golden Calf, as Exodus 32:8}HE reports. "On the plain" alludes to how they complained about not having water, as Exodus 17:3 reports. "Facing Suf" alludes to how they rebelled at the Sea of Reeds (or some say to the idol that Micah made). Rabbi Judah cited Psalms 106:7, "They rebelled at the Sea of Reeds." "Between Paran" alludes to the Twelve Spies, as Numbers 13:3 says, "Moses sent them from the wilderness of Paran." "And Tophel" alludes to the frivolous words (תפלות, tiphlot) they said about the manna. "Lavan" alludes to Koraḥ's mutiny. "Ḥatzerot" alludes to the quails. And in Deuteronomy 9:22, it says, "At Tav'erah, and at Masah, and at Kivrot HaTa'avah." And "Di-zahav" alludes to when Aaron said to them: "Enough (דַּי, dai) of this golden (זָהָב, zahav) sin that you have committed with the Calf!" But Rabbi Eliezer ben Ya'akov said it means "Terrible enough (דַּי, dai) is this sin that Israel was punished to last from now until the resurrection of the dead."[66]

A Tanna in the name of Rabbi deduced from the words "the sons of Korah did not die" in Numbers 26:11 that Providence set up a special place for them to stand on high in Gehinnom.[67] There, Korah's sons sat and sang praises to God. Rabbah bar bar Hana told that once when he was travelling, an Arab showed him where the earth swallowed Korah's congregation. Rabbah bar bar Hana saw two cracks in the ground from which smoke issued. He took a piece of wool, soaked it in water, attached it to the point of his spear, and passed it over the cracks, and the wool was singed. The Arab told Rabbah bar bar Hana to listen, and he heard them saying, "Moses and his Torah are true, but Korah's company are liars." The Arab told Rabbah bar bar Hana that every 30 days Gehinnom caused them to return for judgment, as if they were being stirred like meat in a pot, and every 30 days they said those same words.[68]

Rabbi Judah taught that the same fire that descended from heaven settled on the earth, and did not again return to its former place in heaven, but it entered the Tabernacle. That fire came forth and devoured all the offerings that the Israelites brought in the wilderness, as Leviticus 9:24 does not say, "And there descended fire from heaven," but "And there came forth fire from before the Lord." This was the same fire that came forth and consumed the sons of Aaron, as Leviticus 10:2 says, "And there came forth fire from before the Lord." And that same fire came forth and consumed the company of Korah, as Numbers 16:35 says, "And fire came forth from the Lord." And the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that no person departs from this world until some of that fire, which rested among humanity, passes over that person, as Numbers 11:2 says, "And the fire rested."[69]

Numbers chapter 17

Rabbi Aḥa bar Yaakov read Numbers 17:3 to teach that in matters of sanctity, one always elevates to a higher level. Numbers 17:3 states with regard to the coal pans that the men of Korah's assembly used to burn incense: "The coal pans of these men who have sinned at the cost of their lives, and let them be made beaten plates for a covering of the altar, for they have become sacred because they were brought before the Lord, that they may be a sign to the children of Israel." At first, the coal pans had the status of articles used in the service of the altar, as they contained the incense, but when they were made into a covering for the altar, their status was elevated to that of the altar itself.[70]

Rav taught that anyone who persists in a quarrel transgresses the commandment of Numbers 17:5 that one be not as Korah and his company.[71]

Rabbi Joshua ben Levi explained how, as Numbers 17:11–13 reports, Moses knew what to tell Aaron what to do to make atonement for the people, to stand between the dead and the living, and to check the plague. Rabbi Joshua ben Levi taught that when Moses ascended on high (as Exodus 19:20 reports), the ministering angels asked God what business one born of woman had among them. God told them that Moses had come to receive the Torah. The angels questioned why God was giving to flesh and blood the secret treasure that God had hidden for 974 generations before God created the world. The angels asked, in the words of Psalm 8:8, "What is man, that You are mindful of him, and the son of man, that You think of him?" God told Moses to answer the angels. Moses asked God what was written in the Torah. In Exodus 20:2, God said, "I am the Lord your God, Who brought you out of the Land of Egypt." So Moses asked the angels whether the angels had gone down to Egypt or were enslaved to Pharaoh. As the angels had not, Moses asked them why then God should give them the Torah. Again, Exodus 20:3 says, "You shall have no other gods," so Moses asked the angels whether they lived among peoples that engage in idol worship. Again, Exodus 20:7 (20:8 in the NJPS) says, "Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy," so Moses asked the angels whether they performed work from which they needed to rest. Again, Exodus 20:6 (20:7 in the NJPS) says, "You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain," so Moses asked the angels whether there were any business dealings among them in which they might swear oaths. Again, Exodus 20:11 (20:12 in the NJPS) says, "Honor your father and your mother," so Moses asked the angels whether they had fathers and mothers. Again, Exodus 20:12 (20:13 in the NJPS) says, "You shall not murder; you shall not commit adultery; you shall not steal," so Moses asked the angels whether there was jealousy among them and whether the Evil Tempter was among them. Immediately, the angels conceded that God's plan was correct, and each angel felt moved to love Moses and give him gifts. Even the Angel of Death confided his secret to Moses, and that is how Moses knew what to do when, as Numbers 17:11–13 reports, Moses told Aaron what to do to make atonement for the people, to stand between the dead and the living, and to check the plague.[72]

A Baraita taught that Josiah hid away Aaron's rod with its almonds and blossoms referred to in Numbers 17:23, the Ark referred to in Exodus 37:1–5, the jar of manna referred to in Exodus 16:33, the anointing oil referred to in Exodus 30:22–33, and the coffer that the Philistines sent the Israelites as a gift along with the Ark and concerning which the priests said in 1 Samuel 6:8, “And put the jewels of gold, which you returned Him for a guilt offering, in a coffer by the side thereof [of the Ark]; and send it away that it may go.” Having observed that Deuteronomy 28:36 predicted, “The Lord will bring you and your king . . . to a nation that you have not known,” Josiah ordered the Ark hidden away, as 2 Chronicles 2 Chronicles 35:3 reports, “And he [Josiah] said to the Levites who taught all Israel, that were holy to the Lord, ‘Put the Holy Ark into the house that Solomon the son of David, King of Israel, built; there shall no more be a burden upon your shoulders; now serve the Lord your God and his people Israel.’” Rabbi Eleazar deduced that Josiah hid the anointing oil and the other objects at the same time as the Ark from the common use of the expressions “there” in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and “there” in Exodus 30:6 with regard to the Ark, “to be kept” in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and “to be kept” in Numbers 17:25 with regard to Aaron's rod, and “generations” in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and “generations” in Exodus 30:31 with regard to the anointing oil.[73]

Numbers chapter 18

The Rabbis derived from the words of Numbers 18:2, "That they [the Levites] may be joined to you [Aaron] and minister to you," that the priests watched from upper chambers in the Temple and the Levites from lower chambers. The Gemara taught that in the north of the Temple was the Chamber of the Spark, built like a veranda (open on one or more sides) with a doorway to the non-sacred part, and there the priests kept watch in a chamber above and the Levites below. The Rabbis noted that Numbers 18:2 speaks of "your [Aaron's] service" (and watching was primarily a priestly function). The Gemara rejected the possibility that Numbers 18:2 might have referred to the Levites' service (of carrying the sacred vessels), noting that Numbers 18:4 addresses the Levites' service when it says, "And they shall be joined to you and keep the charge of the Tent of Meeting." The Gemara reasoned that the words of Numbers 18:2, "That they [the Levites] may be joined to you [Aaron] and minister to you," must therefore have addressed the priests' service, and this was to be carried out with the priests watching above and the Levites below.[74]

Rav Ashi read the repetitive language of Leviticus 22:9, "And they shall have charge of My charge"—which referred especially to priests and Levites, whom Numbers 18:3–5 repeatedly charged with warnings—to require safeguards to God's commandments.[75]

Rabbi Jonathan found evidence for the Levites' singing role at Temple services from the warning of Numbers 18:3: "That they [the Levites] do not die, neither they, nor you [Aaron, the priest]." Just as Numbers 18:3 warned about priestly duties at the altar, so (Rabbi Jonathan reasoned) Numbers 18:3 must also address the Levites' duties in the altar service. It was also taught that the words of Numbers 18:3, "That they [the Levites] do not die, neither they, nor you [Aaron, the priest]," mean that priests would incur the death penalty by engaging in Levites' work, and Levites would incur the death penalty by engaging in priests' work, although neither would incur the death penalty by engaging in another's work of their own group (even if they would so incur some penalty for doing so). But Abaye reported a tradition that a singing Levite who did his colleague's work at the gate incurred the death penalty, as Numbers 3:38 says, "And those who were to pitch before the Tabernacle eastward before the Tent of Meeting toward the sun-rising, were Moses and Aaron, . . . and the stranger who drew near was to be put to death." Abaye argued that the "stranger" in Numbers 3:38 could not mean a non-priest, for Numbers 3:10 had mentioned that rule already (and Abaye believed that the Torah would not state anything twice). Rather, reasoned Abaye, Numbers 3:38 must mean a "stranger" to a particular job. It was told, however, that Rabbi Joshua ben Hananyia once tried to assist Rabbi Joḥanan ben Gudgeda (both of whom were Levites) in the fastening of the Temple doors, even though Rabbi Joshua was a singer, not a door-keeper.[76]

A non-Jew asked Shammai to convert him to Judaism, on condition that Shammai appoint him High Priest. Shammai pushed him away with a builder's ruler. The non-Jew then went to Hillel, who converted him. The convert then read Torah, and when he came to the injunction of Numbers 1:51, 3:10, and 18:7 that "the common man who draws near shall be put to death," he asked Hillel to whom the injunction applied. Hillel answered that it applied even to David, King of Israel, who had not been a priest. Thereupon the convert reasoned a fortiori that if the injunction applied to all (non-priestly) Israelites, whom in Exodus 4:22 God had called "my firstborn," how much more so would the injunction apply to a mere convert, who came among the Israelites with just his staff and bag. Then the convert returned to Shammai, quoted the injunction, and remarked on how absurd it had been for him to ask Shammai to appoint him High Priest.[77]

Tractate Terumot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud interpreted the laws of the portion of the crop that was to be given to the priests in Numbers 18:8–13 and Deuteronomy 18:4[78]

In Numbers 18:11, God designated for Aaron and the priests “the heave offering (תְּרוּמַת, terumat) of their gift.” The Mishnah taught that a generous person would give one part out of 40. The House of Shammai said one out of 30. The average person was to give one out of fifty. A stingy person would give one out of 60.[79]

Tractate Bikkurim in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud interpreted the laws of the firstfruits in Exodus 23:19 and 34:26, Numbers 18:13, and Deuteronomy 12:17–18, 18:4, and 26:1–11.[80]

The Mishnah taught that the Torah set no fixed amount for the firstfruits that the Israelites had to bring.[81]

Rabban Simeon ben Gamaliel taught that any baby who lives 30 days is not a nonviable, premature birth (nefel), because Numbers 18:16 says, "And those that are to be redeemed of them from a month old shall you redeem," and as the baby must be redeemed, it follows that the baby is viable.[82]

Tractates Terumot, Ma'aserot, and Ma'aser Sheni in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud interpret the laws of tithes in Leviticus 27:30–33, Numbers 18:21–24, and Deuteronomy 14:22–29 and 26:12–14.[83]

Tractate Demai in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud, interpreted the laws related to produce where one is not sure if it has been properly tithed in accordance with Numbers 18:21–28.[84]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[85]

Numbers chapter 16

Baḥya ibn Paquda taught that because God showed special goodness to a certain family among families in the appointment of the priesthood and the Levites, God charged them with additional duties. But whoever among them rebels against God falls from those high degrees in this world, and will suffer severe pain in the World To Come, as was seen from what befell Korah and his company.[86]

The 12th century French commentator Rashbam wrote that Moses called God "God of the spirits" in Numbers 16:22 as if to say that God knew the spirits and the minds of the rest of the people, and thus knew that they had not sinned.[87] But the 12th century Spanish commentator Abraham ibn Ezra taught that the words "God of the spirits" just explain the word "God," indicating that God could destroy the congregation because God had their spirits in God's hand. Ibn Ezra acknowledged that some say that "God of the spirits" means that God has the power to investigate human souls, and that God knew that one man—Korah—alone sinned and caused the others to sin. But Ibn Ezra wrote that he believed that the words "Separate yourselves from among this congregation" in Numbers 16:21 refer to Korah and his congregation—and not to the entire congregation of Israel—and that God destroyed Korah's congregation.[88]

Numbers chapter 18

Maimonides explained the laws governing the redemption of a firstborn son (פדיון הבן, pidyon haben) in Numbers 18:15–16.[89] Maimonides taught that it is a positive commandment for every Jewish man to redeem his son who is the firstborn of a Jewish mother, as Exodus 34:19 says, "All first issues of the womb are mine," and Numbers 18:15 says, "And you shall surely redeem a firstborn man."[90] Maimonides taught that a mother is not obligated to redeem her son. If a father fails to redeem his son, when the son comes of age, he is obligated to redeem himself.[91] If it is necessary for a man to redeem both himself and his son, he should redeem himself first and then his son. If he only has enough money for one redemption, he should redeem himself.[92] A person who redeems his son recites the blessing: "Blessed are You . . . who sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us concerning the redemption of a son." Afterwards, he recites the shehecheyanu blessing and then gives the redemption money to the Cohen. If a man redeems himself, he should recite the blessing: "Blessed . . . who commanded us to redeem the firstborn" and he should recite the shehecheyanu blessing.[93] The father may pay the redemption in silver or in movable property that has financial worth like that of silver coins.[94] If the Cohen desires to return the redemption to the father, he may. The father should not, however, give it to the Cohen with the intent that he return it. The father must give it to the Cohen with the resolution that he is giving him a present without any reservations.[95] Cohens and Levites are exempt from the redemption of their firstborn, as they served as the redemption of the Israelites' firstborn in the desert.[96] One born to a woman of a priestly or Levite family is exempt, for the matter is dependent on the mother, as indicated by Exodus 13:2 and Numbers 3:12.[97] A baby born by Caesarian section and any subsequent birth are exempt: the first because it did not emerge from the womb, and the second, because it was preceded by another birth.[98] The obligation for redemption takes effect when the baby completes 30 days of life, as Numbers 18:16 says, "And those to be redeemed should be redeemed from the age of a month."[99]

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Numbers chapter 16

James Kugel wrote that early interpreters saw in the juxtaposition of the law of tzitzit in Numbers 15:37–40 with the story of Korah's rebellion in Numbers 16:1–3 a subtle hint as to how Korah might have enlisted his followers. Forcing people to put a special blue tassel on their clothes, ancient interpreters suggested Korah must have argued, was an intolerable intrusion into their lives. Korah asked why, if someone's whole garment was already dyed blue, that person needed to add an extra blue thread to the corner tassel. But this question, ancient interpreters implied, was really a metaphorical version of Korah's complaint in Numbers 16:3: "Everyone in the congregation [of Levites] is holy, and the Lord is in their midst. So why then do you exalt yourselves above the assembly of the Lord?" In other words, Korah asserted that all Levites were part of the same garment and all blue, and asked why Moses and Aaron thought that they were special just because they were the corner thread. In saying this, Kugel argued, Korah set a pattern for would-be revolutionaries thereafter to seek to bring down the ruling powers with the taunt: "What makes you better than the rest of us?" Kugel wrote that ancient interpreters thus taught that Korah was not really interested in changing the system, but merely in taking it over. Korah was thus a dangerous demagogue.[100]

Gunther Plaut reported that source-critics saw two traditions in Numbers 16, a Korah rebellion directed against Aaron and Levitical privilege (assigned to the Priestly source), and an anti-Moses uprising led by Dathan and Abiram (assigned to the J/E source). Plaut wrote that the Korah story appears to reflect a struggle for priestly privilege in which Korah's people, originally full priests and singers, were after a power struggle reduced to doorkeepers. The story of the rebellion of Dathan, Abiram, and members of the tribe of Reuben, Plaut wrote, may represent the memory of an intertribal struggle in which the originally important tribe of Reuben was dislodged from its original preeminence.[101]

Plaut read the words "Korah gathered the whole community" in Numbers 16:19 to indicate that the people did not necessarily side with Korah but readily came out to watch his attack on the establishment. Plaut noted, however, that Numbers 17:6 indicates some dissatisfaction rife among the Israelites. Plaut concluded that by not backing Moses and Aaron, the people exposed themselves to divine retribution.[102]

Robert Alter noted ambiguity about the scope of the noun "congregation" (עֵדָה, edah) in Numbers 16:21. If it means Korah's faction, then in Numbers 16:22, Moses and Aaron pleaded that only the ringleaders be punished, not all 250 rebels. But subsequent occurrences of "community" seem to point to the whole Israelite people, so Alter suggested that Moses and Aaron may have feared that God was exhibiting another impulse to destroy the entire Israelite population and start over again with the two brothers.[103] Nili Fox and Terence Fretheim shared the latter view. Fox wrote that God was apparently ready to annihilate Israel, but Moses and Aaron appealed to God as Creator of humanity in Numbers 16:22a and appealed to God's sense of justice in Numbers 16:22b, arguing that sin must be punished individually rather than communally.[104] Similarly, Fretheim reported that Moses and Aaron interceded arguing that not all should bear the consequences for one person. And Fretheim also saw the phrase "the God of the spirits of all flesh" in Numbers 16:22 (which also appears in Numbers 27:16) to appeal to God as Creator, the One who gives breath to all. In Fretheim's view, God responded positively, separating the congregation from the rebels and their families.[105]

Numbers chapter 18

Robert A. Oden taught that the idea that spoils of holy war were devoted to God (חֵרֶם, cherem), evident in Leviticus 27:28–29, Numbers 18:14, and Deuteronomy 7:26, was revelatory of (1) as "to the victor belong the spoils",[106] then since God owned the spoils, then God must have been the victor and not any human being, and (2) the sacred and religiously obligatory nature of holy war, as participants gained no booty as a motivation for participation.[107]

Jacob Milgrom taught that the verbs used in the laws of the redemption of a firstborn son (פדיון הבן, pidyon haben) in Exodus 13:13–16 and Numbers 3:45–47 and 18:15–16, "natan, kiddesh, he‘evir to the Lord," as well as the use of padah, "ransom," indicate that the firstborn son was considered God's property. Milgrom surmised that this may reflect an ancient rule where the firstborn was expected to care for the burial and worship of his deceased parents. Thus the Bible may be preserving the memory of the firstborn bearing a sacred status, and the replacement of the firstborn by the Levites in Numbers 3:11–13, 40–51; and 8:14–18 may reflect the establishment of a professional priestly class. Milgrom dismissed as without support the theory that the firstborn was originally offered as a sacrifice.[108]

In April 2014, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of Conservative Judaism ruled that women are now equally responsible for observing commandments as men have been. The Committee thus concluded that mothers and fathers are equally responsible for the redemption of their firstborn sons and daughters.[109]

Plaut reported that most Reform Jews have abandoned the ceremony of redemption of the firstborn as inconsistent with Reform Judaism's rejection of matters relating to priestly privilege and special status based upon one's parentage or sibling birth order.[110]

Numbers 18:16 reports that a shekel equals 20 gerahs. This table translates units of weight used in the Bible:[111]

| Unit | Texts | Ancient Equivalent | Modern Equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|

| gerah (גֵּרָה) | Exodus 30:13; Leviticus 27:25; Numbers 3:47; 18:16; Ezekiel 45:12 | 1/20 shekel | 0.6 gram; 0.02 ounce |

| bekah (בֶּקַע) | Genesis 24:22; Exodus 38:26 | 10 gerahs; half shekel | 6 grams; 0.21 ounce |

| pim (פִים) | 1 Samuel 13:21 | 2/3 shekel | 8 grams; 0.28 ounce |

| shekel (שֶּׁקֶל) | Exodus 21:32; 30:13, 15, 24; 38:24, 25, 26, 29 | 20 gerahs; 2 bekahs | 12 grams; 0.42 ounce |

| mina (maneh, מָּנֶה) | 1 Kings 10:17; Ezekiel 45:12; Ezra 2:69; Nehemiah 7:70 | 50 shekels | 0.6 kilogram; 1.32 pounds |

| talent (kikar, כִּכָּר) | Exodus 25:39; 37:24; 38:24, 25, 27, 29 | 3,000 shekels; 60 minas | 36 kilograms; 79.4 pounds |

Commandments

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 5 positive and 4 negative commandments in the parashah.[112]

- To guard the Temple area[113]

- No Levite must do another's work of either a Kohen or a Levite[114]

- One who is not a Kohen must not serve in the sanctuary[115]

- Not to leave the Temple unguarded[116]

- To redeem the firstborn sons and give the money to a Kohen[117]

- Not to redeem the firstborn of a kosher domestic animal[118]

- The Levites must work in the Temple[119]

- To set aside a tithe each planting year and give it to a Levite[120]

- The Levite must set aside a tenth of his tithe[121]

In the liturgy

Some Jews read about how the earth swallowed Korah up in Numbers 16:32 and how the controversy of Korah and his followers in Numbers 16 was not for the sake of Heaven as they study Pirkei Avot chapter 5 on a Sabbath between Passover and Rosh Hashanah.[122]

And similarly, some Jews refer to the 24 priestly gifts deduced from Leviticus 21 and Numbers 18 as they study chapter 6 of Pirkei Avot on another Sabbath between Passover and Rosh Hashanah.[123]

Haftarah

The haftarah for the parashah is 1 Samuel 11:14–12:22.

When the parashah coincides with Shabbat Rosh Chodesh, the haftarah is Isaiah 66:1–24.

Notes

- "Torah Stats—Bemidbar". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved June 17, 2023.

- "Parashat Korach". Hebcal. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bamidbar/Numbers (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2007), pages 112–32.

- Numbers 16:1–2.

- Numbers 16:3.

- Numbers 16:6–7.

- Numbers 16:12.

- Numbers 16:18–19.

- Numbers 16:20–21.

- Numbers 16:22.

- Numbers 16:23–27.

- Numbers 16:28–30.

- Numbers 16:31–34.

- Numbers 16:35.

- Numbers 17:1–5.

- Numbers 17:6.

- Numbers 17:6.

- Numbers 17:9–10.

- Numbers 17:11–12.

- Numbers 17:13–14.

- Numbers 17:16–19.

- Numbers 17:23.

- Numbers 17:25.

- Numbers 17:27–28.

- Numbers 18:1.

- Numbers 18:2–6.

- Numbers 18:7.

- Numbers 18:8–13.

- Numbers 18:12–16.

- Numbers 18:19.

- Numbers 18:20.

- Numbers 18:21–24.

- Numbers 18:26–29.

- See, e.g., Richard Eisenberg, "A Complete Triennial Cycle for Reading the Torah," in Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement: 1986–1990 (New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2001), pages 383–418.

- For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer, "Inner-biblical Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, The Jewish Study Bible, 2nd edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), pages 1835–41.

- See, e.g., Numbers 2:1, 4:1, and 19:1. The Pulpit Commentary suggests that this change in the form of address may point to a later date after the gainsaying of Korah, when the separate position of Aaron as the head of the priesthood was more fully recognized, and Aaron was somewhat less under the shadow of Moses. See Pulpit Commentary on Numbers 18:1.

- For more on early nonrabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Esther Eshel, "Early Nonrabbinic Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, Jewish Study Bible, 2nd edition, pages 1841–59.

- Pseudo-Philo. Biblical Antiquities 16:1. 1st–2nd century CE. In, e.g., The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: Volume 2: Expansions of the "Old Testament" and Legends, Wisdom and Philosophical Literature, Prayers, Psalms, and Odes, Fragments of Lost Judeo-Hellenistic works. Edited by James H. Charlesworth. New York: Anchor Bible, 1985.

- Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews book 4, chapter 2, paragraph 2. Circa 93–94. In, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, page 102. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987.

- Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews book 4, chapter 3, paragraph 2. In, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, page 105.

- For more on classical rabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Yaakov Elman, "Classical Rabbinic Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, Jewish Study Bible, 2nd edition, pages 1859–78.

- Jerusalem Talmud Sanhedrin 10:1.

- Genesis Rabbah 98:5. Land of Israel, 5th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 2, page 952. London: Soncino Press, 1939.

- Numbers Rabbah 18:5. 12th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 6, pages 713–14. London: Soncino Press, 1939. See also Numbers Rabbah 3:12. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 89–91.

- Numbers Rabbah 3:12. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 89–91.

- Midrash Tanḥuma Korah 1.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 109b.

- Mekhilta of Rabbi Simeon chapter 46, paragraph 2:4. Land of Israel, 5th century. In, e.g., Mekhilta de-Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai. Translated by W. David Nelson, page 199. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2006.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 109b–10a.

- Mishnah Avot 5:17.

- Numbers Rabbah 5:5. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, page 148.

- Numbers Rabbah 13:5. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 6, pages 513–15.

- Babylonian Talmud Megillah 9a–b.

- Babylonian Talmud Sotah 13b.

- Babylonian Talmud Moed Katan 16a.

- Midrash Tanḥuma Korach 6.

- See Exodus 6:13, 7:8, 9:8, 12:1, 12:43, 12:50; Leviticus 11:1, 13:1, 14:33, 15:1; Numbers 2:1, 4:1, 4:17 14:26, 16:20, 19:1, 20:12, 20:23.

- Numbers Rabbah 2:1. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, page 22.

- Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 21b; see also Babylonian Talmud Megillah 23b, Sanhedrin 74b.

- Leviticus Rabbah 4:6. Land of Israel, 5th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, page 55. London: Soncino Press, 1939.

- Song of Songs Rabbah 6:11 [6:26]. 6th–7th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Song of Songs. Translated by Maurice Simon, volume 9, pages 270–72. London: Soncino Press, 1939. See also Pesikta Rabbati. Circa 845 CE. In, e.g., Pesikta Rabbati: Discourses for Feasts, Fasts, and Special Sabbaths. Translated by William G. Braude, pages 198, 200. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968.

- Midrash Tanḥuma Korach 7; see also Numbers Rabbah 18:11.

- Midrash Tanḥuma Korach 3.

- Avot 5:6.

- Mishnah Sanhedrin 10:3; Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 108a, 109b.

- Avot of Rabbi Natan, chapter 34 (700–900 CE), in, e.g., Judah Goldin, translator, The Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1955, 1983), pages 136–37.

- Babylonian Talmud Megillah 14a, Sanhedrin 110a.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 110a–b.

- Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 53. Early 9th century. In, e.g., Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer. Translated and annotated by Gerald Friedlander, pages 429–30. London, 1916. Reprinted New York: Hermon Press, 1970.

- Babylonian Talmud Menachot 99a.

- Numbers Rabbah 18:20. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 6, page 732.

- Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 88b–89a.

- Babylonian Talmud Horayot 12a.

- Babylonian Talmud Tamid 26b.

- Babylonian Talmud Moed Katan 5a.

- Babylonian Talmud Arakhin 11b.

- Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 31a.

- Mishnah Terumot 1:1–11:10; Tosefta Terumot 1:1–10:18; Jerusalem Talmud Terumot 1a–107a.

- Mishnah Terumot 4:3.

- Mishnah Bikkurim 1:1–3:12; Tosefta Bikkurim 1:1–2:16; Jerusalem Talmud Bikkurim 1a–26b.

- Mishnah Peah 1:1; Tosefta Peah 1:1; Jerusalem Talmud Peah 1a.

- Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 135b.

- Mishnah Terumot 1:1–11:10, Maasrot 1:1–5:8, and Maaser Sheni 1:1–5:15; Tosefta Terumot 1:1–10:18, Maasrot 1:1–3:16, and Maaser Sheni 1:1–5:30; Jerusalem Talmud Terumot 1a–107a, Maasrot 1a–46a, and Maaser Sheni 1a–59b.

- Mishnah Demai 1:1–7:8; Tosefta Demai 1:1–8:24; Jerusalem Talmud Demai 1a–77b.

- For more on medieval Jewish interpretation, see, e.g., Barry D. Walfish, "Medieval Jewish Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, Jewish Study Bible, 2nd edition, pages 1891–1915.

- Baḥya ibn Paquda, Chovot HaLevavot (Duties of the Heart), section 3, chapter 6 (Zaragoza, Al-Andalus, circa 1080), in, e.g., Bachya ben Joseph ibn Paquda, Duties of the Heart, translated by Yehuda ibn Tibbon and Daniel Haberman (Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1996), volume 1, pages 304–07.

- Rashbam. Commentary on the Torah. Troyes, early 12th century. In, e.g., Rashbam's Commentary on Leviticus and Numbers: An Annotated Translation. Edited and translated by Martin I. Lockshin, page 231. Providence, Rhode Island: Brown Judaic Studies, 2001.

- Abraham ibn Ezra. Commentary on the Torah. Mid-12th century. In, e.g., Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Numbers (Ba-Midbar). Translated and annotated by H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, pages 133–34. New York: Menorah Publishing Company, 1999.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11. Egypt, circa 1170–1180. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 688–703. New York: Moznaim Publishing, 2005.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 1. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 688–89.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 2. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 690–91.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 3. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 690–91.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 5. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 690–91.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 6. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 690–93.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 8. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 692–93.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 9. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 692–93.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 10. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 692–94.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 16. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 696–97.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Bikkurim, chapter 11, ¶ 17. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 696–97.

- James L. Kugel. How To Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now, pages 331–33. New York: Free Press, 2007.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition. Revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern, page 1012. New York: Union for Reform Judaism, 2006.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition. Revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern, page 1004.

- Robert Alter. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary, pages 765–66. New York: W.W. Norton, 2004.

- Nili S. Fox, "Numbers," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, Jewish Study Bible, 2nd edition, page 302.

- Terence E. Fretheim, "Numbers," in Michael D. Coogan, Marc Z. Brettler, Carol A. Newsom, and Pheme Perkins, editors, The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version with the Apocrypha: An Ecumenical Study Bible (New York: Oxford University Press, Revised 4th Edition 2010), page 214.

- William L. Marcy, Speech in the United States Senate (January 1832), quoted in John Bartlett, Familiar Quotations: A Collection of Passages, Phrases, and Proverbs Traced to Their Sources in Ancient and Modern Literature, 17th edition, edited by Justin Kaplan (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1992), page 398.

- Robert A. Oden, The Old Testament: An Introduction, lecture 2 (Chantilly, Virginia: The Teaching Company, 1992).

- Jacob Milgrom. The JPS Torah Commentary: Numbers: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, page 432. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1990.

- Pamela Barmash. “Women and Mitzvot.” Y.D. 246:6 New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2014.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition. Revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern, page 1015.

- Bruce Wells. "Exodus". In Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary. Edited by John H. Walton, volume 1, page 258. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2009.

- Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, volume 4, pages 119–59. Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1988.

- Numbers 18:2

- Numbers 18:3

- Numbers 18:4

- Numbers 18:5

- Numbers 18:15

- Numbers 18:17

- Numbers 18:23

- Numbers 18:24

- Numbers 18:26

- The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals with an Interlinear Translation. Edited by Menachem Davis, pages 571, 577. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002.

- The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals with an Interlinear Translation. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 587.

Further reading

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Biblical

- Exodus 13:1–2 (firstborn); 13:12–13 (firstborn); 22:28–29 (firstborn).

- Numbers 3:11–13 (firstborn); 26:9–11 (Korach, Dathan, Abiram).

- Deuteronomy 15:19–23 (firstborn).

- 1 Samuel 12:3 (not having taken a donkey).

- Jeremiah 31:8 (firstborn).

- Ezekiel 7:10 (rod blossomed); 8:9–12 (elders burning incense); 18 (individual responsibility).

- Psalms 16:5 (God as inheritance); 55:16 (go down alive into the nether-world); 105:26 (Moses as God's chosen); 106:16–18, 29–30 (rebellion and earth swallowing; plague as God's punishment).

Early nonrabbinic

- Pseudo-Philo 16:1–17:4.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 4:2:1–4, 3:1–4, 4:1–2, 4. Circa 93–94. In, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, pages 102–07. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987.

- Jude 1:11 (Korah's rebellion).

- Pausanias. Description of Greece, 2:31:10. Greece, 2nd Century C.E. (After Heracles leaned his club against the image of Hermes, the club took root and grew.).

- Qur'an: 28:76–82; 29:39; 40:24–25. Arabia, circa 609–632. In, e.g., The Meaning of the Holy Qur'an. Translated by Abdullah Yusuf Ali, pages 981–84, 996, 1211-12. Beltsville, Maryland: Amana Publications, 10th edition, 1997. And in The Qur'an With Annotated Interpretation in Modern English. Translated by Ali Ünal, pages 815–17, 828, 965. Clifton, New Jersey: Tughra Books, 2015. (In the Qur'an, Korah is called Qarun.)

Classical rabbinic

- Mishnah: Demai 1:1–7:8; Terumot 1:1–11:10; Challah 1:3; 4:9; Bikkurim 1:1–3:12; Chagigah 1:4; Sanhedrin 9:6; 10:3; Avot 5:6, 17; Bekhorot 8:8. Land of Israel, circa 200 C.E. In, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 36–49, 93–120, 148, 157, 329, 345–53, 604–05, 686, 688, 806. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. And in, e.g., The Oxford Annotated Mishnah. Edited by Shaye J. D. Cohen, Robert Goldenberg, and Hayim Lapin. New York: Oxford University Press, 2022.

- Tosefta: Demai 1:1–8:24; Terumot 1:1–10:18; Maaser Sheni 3:11; Challah 2:7, 9; Shabbat 15:7; Chagigah 3:19; Sotah 7:4; Sanhedrin 13:9; Bekhorot 1:5. Land of Israel, circa 300 C.E. In, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, pages 77–202, 313, 339, 414, 677, 861; volume 2, pages 1190, 1469. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Demai 1a–77b; Terumot 1a–107a; Maaser Sheni 4a, 5a, 53b–54a; Challah 9b, 23b, 29a, 33a; Orlah 18a, 20a; Bikkurim 1a–26b; Pesachim 42b, 58a; Yoma 11a; Yevamot 51b–52a, 65b, 73b–74a; Ketubot 36a; Gittin 27b; Sanhedrin 11a, 60b, 62b, 68a–b; Avodah Zarah 27b. Tiberias, Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. In, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volumes 4, 7–8, 10–12, 18–19, 21, 30–31, 39, 44–45, 48. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2006–2018. And in, e.g., The Jerusalem Talmud: A Translation and Commentary. Edited by Jacob Neusner and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, B. Barry Levy, and Edward Goldman. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2009.

- Genesis Rabbah 19:2; 22:10; 26:7; 43:9. Land of Israel, 5th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 1, pages 149, 189–90, 217–19, 358–59; volume 2, pages 528, 656–57, 817, 899, 952–53, 980. London: Soncino Press, 1939.

- Mekhilta of Rabbi Simeon 19:3:2; 43:1:13; 46:2:4; 79:4:2; 84:1:9. Land of Israel, 5th century. In, e.g., Mekhilta de-Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai. Translated by W. David Nelson, pages 77, 182, 199, 367, 377. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2006.

.jpg.webp)

- Babylonian Talmud: Berakhot 21b, 45a, 47a–b; Shabbat 25a, 31a, 26a, 88b–89a, 127b, 135b; Eruvin 19a, 31b; Pesachim 23a, 34a, 35b, 54a, 64b, 73a, 121b; Yoma 24a, 27a, 44a, 45b, 52b, 74b; 9a; Beitzah 3b, 12b–13b; Rosh Hashanah 12b; 9b, 23b; Moed Katan 5a–b, 12a, 13a, 16a, 18b, 28a; Chagigah 7b, 10b, 11b; Yevamot 74a, 85b–86b, 89b, 99b; Ketubot 8b, 72a, 102a; Nedarim 7b, 12b, 18b, 38a, 39b, 64b; Nazir 4b; Sotah 2a, 13b, 15a; Gittin 11b, 23b, 25a, 30b, 52a; Kiddushin 11b, 17a, 29a, 46b, 52b–53a; Bava Kamma 13a, 67a, 69b, 78a, 79a, 80a, 110b, 114a, 115b; Bava Metzia 6b, 22a, 56a, 71b, 88b, 102b ; Bava Batra 74a, 84b, 112a, 118b, 143a; Sanhedrin 17a, 37b, 52a–b, 74b, 82b–84a, 90b, 108a, 109b–10a; Makkot 4a, 12a, 13a, 14b, 17a–b, 19a–b, 23b; Shevuot 4b, 17b, 39a; Avodah Zarah 15a, 24b; Horayot 12a; Zevachim 16a, 28a, 32a, 37a, 44b–45a, 49b, 57a, 60b, 63a, 73a, 81a, 88b, 91a, 97b, 102b; Menachot 9a, 19b, 21b, 23a, 37a, 54b, 58a, 73a, 77b, 83a, 84b, 99a; Chullin 68a, 99a, 120b, 130a, 131a–32b, 133b, 134b, 135b–36a; Bekhorot 3b–4b, 5b, 6b–7a, 10b, 11b–12b, 17a, 26b, 27b, 31b–33a, 34a, 47b, 49a, 50a, 51a–b, 53b, 54b, 56b, 58b–59a, 60a; Arakhin 4a, 11b, 16a, 28b–29a; Temurah 3a, 4b–5b, 8a, 21a–b, 24a; Keritot 4a, 5b; Meilah 8b; Tamid 26b; Niddah 26a, 29a. Sasanian Empire, 6th Century. In, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 volumes. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2006.

Medieval

- Avot of Rabbi Natan, 36:3. Circa 700–900 C.E. In, e.g., The Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan. Translated by Judah Goldin, page 149. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1955. The Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan: An Analytical Translation and Explanation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, 217. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1986.

- Midrash Tanḥuma Korach. Circa 775–900 C.E. In, e.g., The Metsudah Midrash Tanchuma. Translated and annotated by Avrohom Davis, edited by Yaakov Y.H. Pupko, volume 7 (Bamidbar volume 2), pages 1–56.

- Tanna Devei Eliyahu. Seder Eliyyahu Rabbah 67, 77, 83, 106, 117. 10th Century. In, e.g., Tanna Debe Eliyyahu: The Lore of the School of Elijah. Translated by William G. Braude and Israel J. Kapstein, pages 150, 172, 183, 233, 256. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1981.

- Midrash Tehillim 1:15; 19:1; 26:4; 24:7; 32:1; 45:1, 4; 46:3; 49:3; 90:5; 132:1, 3. 10th century. In, e.g., The Midrash on the Psalms. Translated by William G. Braude, volume 1, pages 20–22. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959. LCCN 58-6535.

- Rashi. Commentary. Numbers 16–18. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. In, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, volume 4, pages 189–224. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997.

- Rashbam. Commentary on the Torah. Troyes, early 12th century. In, e.g., Rashbam's Commentary on Leviticus and Numbers: An Annotated Translation. Edited and translated by Martin I. Lockshin, pages 225–46. Providence: Brown Judaic Studies, 2001.

- Numbers Rabbah 18:1–23. 12th Century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki. London: Soncino Press, 1939.

- Abraham ibn Ezra. Commentary on the Torah. Mid-12th century. In, e.g., Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Numbers (Ba-Midbar). Translated and annotated by H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, pages 126–51. New York: Menorah Publishing Company, 1999.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah, Structure. Cairo, Egypt, circa 1170–1180.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Talmud Torah (The Laws of Torah Study), chapter 3, ¶ 13. Egypt, circa 1170–1180. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Hilchot De'ot: The Laws of Personality Development: and Hilchot Talmud Torah: The Laws of Torah Study. Translated by Za'ev Abramson and Eliyahu Touger, volume 2, pages 206–09. New York: Moznaim Publishing, 1989.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Matnot Aniyiim (The Laws of Gifts to the Poor), chapter 6, ¶ 2; Hilchot Terumot (The Laws of Priestly Offerings); Hilchot Ma'aser (The Laws of Tithes); Hilchot Bikkurim (The Laws of First Fruits); Hilchot Shemita V'Yovel (The Laws of the Sabbatical and Jubilee Years), chapter 13, ¶ 12. Egypt, circa 1170–1180. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 154–55, 196–499, 600–715, 834–35. New York: Moznaim Publishing, 2005.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Kli Hamikdash (The Laws of the Temple Utensils), chapter 3, ¶ 1. Egypt, circa 1170–1180. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Ha'Avodah: The Book of (Temple) Service. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 148–51. New York: Moznaim Publishing, 2007.

- Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed, part 1, chapters 15, 20. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. In, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, pages 25, 29. New York: Dover Publications, 1956.

- Hezekiah ben Manoah. Hizkuni. France, circa 1240. In, e.g., Chizkiyahu ben Manoach. Chizkuni: Torah Commentary. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 933–50. Jerusalem: Ktav Publishers, 2013.

- Nachmanides. Commentary on the Torah. Jerusalem, circa 1270. In, e.g., Ramban (Nachmanides): Commentary on the Torah: Numbers. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 4, pages 158–93. New York: Shilo Publishing House, 1975.

- Zohar part 3, pages 176a–178b. Spain, late 13th Century. In, e.g., The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 volumes. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

- Jacob ben Asher (Baal Ha-Turim). Rimze Ba'al ha-Turim. Early 14th century. In, e.g., Baal Haturim Chumash: Bamidbar/Numbers. Translated by Eliyahu Touger; edited and annotated by Avie Gold, volume 4, pages 1547–79. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2003.

- Jacob ben Asher. Perush Al ha-Torah. Early 14th century. In, e.g., Yaakov ben Asher. Tur on the Torah. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 1101–20. Jerusalem: Lambda Publishers, 2005.

- Isaac ben Moses Arama. Akedat Yizhak (The Binding of Isaac). Late 15th century. In, e.g., Yitzchak Arama. Akeydat Yitzchak: Commentary of Rabbi Yitzchak Arama on the Torah. Translated and condensed by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 728–41. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2001.

Modern

- Isaac Abravanel. Commentary on the Torah. Italy, between 1492–1509. In, e.g., Abarbanel: Selected Commentaries on the Torah: Volume 4: Bamidbar/Numbers. Translated and annotated by Israel Lazar, pages 160–88. Brooklyn: CreateSpace, 2015.

- Obadiah ben Jacob Sforno. Commentary on the Torah. Venice, 1567. In, e.g., Sforno: Commentary on the Torah. Translation and explanatory notes by Raphael Pelcovitz, pages 730–45. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997.

- Moshe Alshich. Commentary on the Torah. Safed, circa 1593. In, e.g., Moshe Alshich. Midrash of Rabbi Moshe Alshich on the Torah. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 865–74. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2000.

- Avraham Yehoshua Heschel. Commentaries on the Torah. Cracow, Poland, mid 17th century. Compiled as Chanukat HaTorah. Edited by Chanoch Henoch Erzohn. Piotrkow, Poland, 1900. In Avraham Yehoshua Heschel. Chanukas HaTorah: Mystical Insights of Rav Avraham Yehoshua Heschel on Chumash. Translated by Avraham Peretz Friedman, pages 260–64. Southfield, Michigan: Targum Press/Feldheim Publishers, 2004.

.jpg.webp)

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan, 3:38, 40, 42. England, 1651. Reprint edited by C. B. Macpherson, pages 485–86, 505, 563–64. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Classics, 1982.

- Shabbethai Bass. Sifsei Chachamim. Amsterdam, 1680. In, e.g., Sefer Bamidbar: From the Five Books of the Torah: Chumash: Targum Okelos: Rashi: Sifsei Chachamim: Yalkut: Haftaros, translated by Avrohom Y. Davis, pages 270–327. Lakewood Township, New Jersey: Metsudah Publications, 2013.

- Chaim ibn Attar. Ohr ha-Chaim. Venice, 1742. In Chayim ben Attar. Or Hachayim: Commentary on the Torah. Translated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1496–528. Brooklyn: Lambda Publishers, 1999.

- Samson Raphael Hirsch. Horeb: A Philosophy of Jewish Laws and Observances. Translated by Isidore Grunfeld, pages 189–95, 261–65. London: Soncino Press, 1962. Reprinted 2002. Originally published as Horeb, Versuche über Jissroel's Pflichten in der Zerstreuung. Germany, 1837.

- Samuel David Luzzatto (Shadal). Commentary on the Torah. Padua, 1871. In, e.g., Samuel David Luzzatto. Torah Commentary. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 1060–71. New York: Lambda Publishers, 2012.

- H. Clay Trumbull. The Salt Covenant. New York, 1899. In Kirkwood, Missouri: Impact Christian Books, 1999.

- Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter. Sefat Emet. Góra Kalwaria (Ger), Poland, before 1906. Excerpted in The Language of Truth: The Torah Commentary of Sefat Emet. Translated and interpreted by Arthur Green, pages 243–48. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1998. Reprinted 2012.

- Hermann Cohen. Religion of Reason: Out of the Sources of Judaism. Translated with an introduction by Simon Kaplan; introductory essays by Leo Strauss, page 431. New York: Ungar, 1972. Reprinted Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995. Originally published as Religion der Vernunft aus den Quellen des Judentums. Leipzig: Gustav Fock, 1919.

- Alexander Alan Steinbach. Sabbath Queen: Fifty-four Bible Talks to the Young Based on Each Portion of the Pentateuch, pages 119–22. New York: Behrman's Jewish Book House, 1936.

- Julius H. Greenstone. Numbers: With Commentary: The Holy Scriptures, pages 164–200. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1939. Reprinted by Literary Licensing, 2011.

- Thomas Mann. Joseph and His Brothers. Translated by John E. Woods, page 55. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. Originally published as Joseph und seine Brüder. Stockholm: Bermann-Fischer Verlag, 1943.

- A. M. Klein. "Candle Lights." Canada, 1944. In The Collected Poems of A.M. Klein, page 13. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1974.

- Jacob Milgrom. "First fruits, OT." In The Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible. Supp. volume, pages 336–37. Nashville, Tennessee: Abingdon, 1976.

- Joseph B. Soloveitchik. "The 'Common-Sense' Rebellion Against Torah Authority." In Reflection of the Rav: Lessons in Jewish Thought. Adapted by Abraham R. Besdin, pages 139–49. Jerusalem: Department for Torah Education and Culture in the Diaspora of the World Zionist Organization, 1979. In Ktav Publishing, 2nd edition, 1993.

- Philip J. Budd. Word Biblical Commentary: Volume 5: Numbers, pages 178–207. Waco, Texas: Word Books, 1984.

- Pinchas H. Peli. Torah Today: A Renewed Encounter with Scripture, pages 173–75. Washington, D.C.: B'nai B'rith Books, 1987.

- Jacob Milgrom. The JPS Torah Commentary: Numbers: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, pages 129–57, 414–36. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1990.

- Howard Handler. "Pidyon HaBen and Caesarean Sections." New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1991. YD 305:24.1991. In Responsa: 1991–2000: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by Kassel Abelson and David J. Fine, pages 171–74. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2002.

- Baruch A. Levine. Numbers 1–20, volume 4, pages 403–53. New York: Anchor Bible, 1993.

- Gerald Skolnik. "Should There Be a Special Ceremony in Recognition of a Firstborn Female Child?" New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1993. YD 305:1.1993. In Responsa: 1991–2000: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by Kassel Abelson and David J. Fine, pages 163–65 New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2002.

- Mary Douglas. In the Wilderness: The Doctrine of Defilement in the Book of Numbers, pages 40, 59, 84, 103, 110–12, 122–23, 125, 130–33, 138, 140, 145, 147, 150, 194–95, 203, 211, 246. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. Reprinted 2004.

- Elliot N. Dorff. "Artificial Insemination, Egg Donation and Adoption." New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1994. EH 1:3.1994. In Responsa: 1991–2000: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by Kassel Abelson and David J. Fine, pages 461, 497. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2002. (implications of the law of the firstborn son for deciding whether a child born from a donated egg is Jewish).

- Judith S. Antonelli. "Korach's Rebellion." In In the Image of God: A Feminist Commentary on the Torah, pages 357–60. Northvale, New Jersey: Jason Aronson, 1995.

- Vernon Kurtz. "Delay of Pidyon HaBen" New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1995. YD 305:11.1995. In Responsa: 1991–2000: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by Kassel Abelson and David J. Fine, pages 166–70. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2002.

- Ellen Frankel. The Five Books of Miriam: A Woman's Commentary on the Torah, pages 220–23. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1996.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Haftarah Commentary, pages 366–74. New York: UAHC Press, 1996.

- Sorel Goldberg Loeb and Barbara Binder Kadden. Teaching Torah: A Treasury of Insights and Activities, pages 254–59. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 1997.

- Elyse D. Frishman. "Authority, Status, Power." In The Women's Torah Commentary: New Insights from Women Rabbis on the 54 Weekly Torah Portions. Edited by Elyse Goldstein, pages 286–93. Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2000.

- Dennis T. Olson. "Numbers." In The HarperCollins Bible Commentary. Edited by James L. Mays, pages 175–78. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, revised edition, 2000.

- Elie Wiesel. "Korah." Bible Review, volume 16 (number 3) (June 2000): pages 12–15.

- Lainie Blum Cogan and Judy Weiss. Teaching Haftarah: Background, Insights, and Strategies, pages 53–61. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 2002.