Tonality diamond

In music theory and tuning, a tonality diamond is a two-dimensional diagram of ratios in which one dimension is the Otonality and one the Utonality.[1] Thus the n-limit tonality diamond ("limit" here is in the sense of odd limit, not prime limit) is an arrangement in diamond-shape of the set of rational numbers r, , such that the odd part of both the numerator and the denominator of r, when reduced to lowest terms, is less than or equal to the fixed odd number n. Equivalently, the diamond may be considered as a set of pitch classes, where a pitch class is an equivalence class of pitches under octave equivalence. The tonality diamond is often regarded as comprising the set of consonances of the n-limit. Although originally invented by Max Friedrich Meyer,[2] the tonality diamond is now most associated with Harry Partch ("Many theorists of just intonation consider the tonality diamond Partch's greatest contribution to microtonal theory."[3]).

The diamond arrangement

Partch arranged the elements of the tonality diamond in the shape of a rhombus, and subdivided into (n+1)2/4 smaller rhombuses. Along the upper left side of the rhombus are placed the odd numbers from 1 to n, each reduced to the octave (divided by the minimum power of 2 such that ). These intervals are then arranged in ascending order. Along the lower left side are placed the corresponding reciprocals, 1 to 1/n, also reduced to the octave (here, multiplied by the minimum power of 2 such that ). These are placed in descending order. At all other locations are placed the product of the diagonally upper- and lower-left intervals, reduced to the octave. This gives all the elements of the tonality diamond, with some repetition. Diagonals sloping in one direction form Otonalities and the diagonals in the other direction form Utonalities. One of Partch's instruments, the diamond marimba, is arranged according to the tonality diamond.

Numerary nexus

A numerary nexus is an identity shared by two or more interval ratios in their numerator or denominator, with different identities in the other.[1] For example, in the Otonality the denominator is always 1, thus 1 is the numerary nexus:

In the Utonality the numerator is always 1 and the numerary nexus is thus also 1:

For example, in a tonality diamond, such as Harry Partch's 11-limit diamond, each ratio of a right slanting row shares a numerator and each ratio of a left slanting row shares an denominator. Each ratio of the upper left row has 7 as a denominator, while each ratio of the upper right row has 7 (or 14) as a numerator.

5-limit

| 3⁄2 | |||||

| 5⁄4 | 6⁄5 | ||||

| 1⁄1 | 1⁄1 | 1⁄1 | |||

| 8⁄5 | 5⁄3 | ||||

| 4⁄3 |

| ⓘ | |||||

| ⓘ | ⓘ | ||||

| ⓘ | 1⁄1 | 1⁄1 | |||

| ⓘ | ⓘ | ||||

| ⓘ |

This diamond contains three identities (1, 3, 5).

7-limit

| 7⁄4 | ||||||

| 3⁄2 | 7⁄5 | |||||

| 5⁄4 | 6⁄5 | 7⁄6 | ||||

| 1⁄1 | 1⁄1 | 1⁄1 | 1⁄1 | |||

| 8⁄5 | 5⁄3 | 12⁄7 | ||||

| 4⁄3 | 10⁄7 | |||||

| 8⁄7 |

This diamond contains four identities (1, 3, 5, 7).

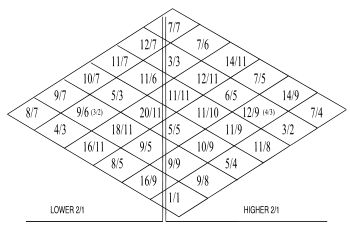

11-limit

This diamond contains six identities (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11). Harry Partch used the 11-limit tonality diamond, but flipped it 90 degrees.

15-limit

| 15⁄8 | ||||||||||||||

| 7⁄4 | 5⁄3 | |||||||||||||

| 13⁄8 | 14⁄9 | 3⁄2 | ||||||||||||

| 3⁄2 | 13⁄9 | 7⁄5 | 15⁄11 | |||||||||||

| 11⁄8 | 4⁄3 | 13⁄10 | 14⁄11 | 5⁄4 | ||||||||||

| 5⁄4 | 11⁄9 | 6⁄5 | 13⁄11 | 7⁄6 | 15⁄13 | |||||||||

| 9⁄8 | 10⁄9 | 11⁄10 | 12⁄11 | 13⁄12 | 14⁄13 | 15⁄14 | ||||||||

| 1⁄1 | 1⁄1 | 1⁄1 | 1⁄1 | 1⁄1 | 1⁄1 | 1⁄1 | 1⁄1 | |||||||

| 16⁄9 | 9⁄5 | 20⁄11 | 11⁄6 | 24⁄13 | 13⁄7 | 28⁄15 | ||||||||

| 8⁄5 | 18⁄11 | 5⁄3 | 22⁄13 | 12⁄7 | 26⁄15 | |||||||||

| 16⁄11 | 3⁄2 | 20⁄13 | 11⁄7 | 8⁄5 | ||||||||||

| 4⁄3 | 18⁄13 | 10⁄7 | 22⁄15 | |||||||||||

| 16⁄13 | 9⁄7 | 4⁄3 | ||||||||||||

| 8⁄7 | 6⁄5 | |||||||||||||

| 16⁄15 |

This diamond contains eight identities (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15).

Geometry of the tonality diamond

The five- and seven-limit tonality diamonds exhibit a highly regular geometry within the modulatory space, meaning all non-unison elements of the diamond are only one unit from the unison. The five-limit diamond then becomes a regular hexagon surrounding the unison, and the seven-limit diamond a cuboctahedron surrounding the unison.. Further examples of lattices of diamonds ranging from the triadic to the ogdoadic diamond have been realised by Erv Wilson where each interval is given its own unique direction.[4]

Properties of the tonality diamond

Three properties of the tonality diamond and the ratios contained:

- All ratios between neighboring ratios are superparticular ratios, those with a difference of 1 between numerator and denominator.[5]

- Ratios with relatively lower numbers have more space between them than ratios with higher numbers.[5]

- The system, including the ratios between ratios, is symmetrical within the octave when measured in cents not in ratios.[5]

For example:

| 5-limit tonality diamond, ordered least to greatest | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio | 1⁄1 | 6⁄5 | 5⁄4 | 4⁄3 | 3⁄2 | 8⁄5 | 5⁄3 | 2⁄1 | ||||||||

| Cents | 0 | 315.64 | 386.31 | 498.04 | 701.96 | 813.69 | 884.36 | 1200 | ||||||||

| Width | 315.64 | 70.67 | 111.73 | 203.91 | 111.73 | 70.67 | 315.64 | |||||||||

- The ratio between 6⁄5 and 5⁄4 (and 8⁄5 and 5⁄3) is 25⁄24.

- The ratios with relatively low numbers 4⁄3 and 3⁄2 are 203.91 cents apart, while the ratios with relatively high numbers 6⁄5 and 5⁄4 are 70.67 cents apart.

- The ratio between the lowest and 2nd lowest and the highest and 2nd highest ratios are the same, and so on.

Size of the tonality diamond

If φ(n) is Euler's totient function, which gives the number of positive integers less than n and relatively prime to n, that is, it counts the integers less than n which share no common factor with n, and if d(n) denotes the size of the n-limit tonality diamond, we have the formula

From this we can conclude that the rate of growth of the tonality diamond is asymptotically equal to . The first few values are the important ones, and the fact that the size of the diamond grows as the square of the size of the odd limit tells us that it becomes large fairly quickly. There are seven members to the 5-limit diamond, 13 to the 7-limit diamond, 19 to the 9-limit diamond, 29 to the 11-limit diamond, 41 to the 13-limit diamond, and 49 to the 15-limit diamond; these suffice for most purposes.

Translation to string length ratios

Yuri Landman published an otonality and utonality diagram that clarifies the relationship of Partch's tonality diamonds to the harmonic series and string lengths (as Partch also used in his Kitharas) and Landmans Moodswinger instrument.[6]

In Partch's ratios, the over number corresponds to the amount of equal divisions of a vibrating string and the under number corresponds to the which division the string length is shortened to. 5⁄4 for example is derived from dividing the string to 5 equal parts and shortening the length to the 4th part from the bottom. In Landmans diagram these numbers is inverted, changing the frequency ratios into string length ratios.

See also

References

- Rasch, Rudolph (2000). "A Word or Two on the Tunings of Harry Partch", Harry Partch: An Anthology of Critical Perspectives, p.28. Dunn, David, ed. ISBN 90-5755-065-2.

- Forster, Cristiano (2000). "Musical Mathematics: Meyer's Diamond", Chrysalis-Foundation.org. Accessed: December 09 2016.

- Granade, S. Andrew (2014). Harry Partch, Hobo Composer, p.295. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781580464956>

- "Diamond Lattices", The Wilson Archives, Anaphoria.com. Accessed: December 09 2016.

- Rasch (2000), p.30.

- http://www.hypercustom.nl/utonaldiagram.jpg