Nusrati

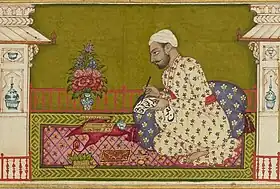

Muḥammad Nuṣrat (died 1674), called Nuṣratī ('victorious'),[1] was a Deccani Urdu poet.[2]

Life

Nuṣratī was born in the Carnatic region into an elite Muslim family of Brahmin origin.[3] He lived for a time as a Sufi dervish before moving to Bījāpūr.[2] There he was made a mansabdar under Sultan ʿAlī II (r. 1656–1672) of the ʿĀdil-Shāhī dynasty.[4] For his poem ʿAlī-nāma (c. 1665), he was named poet laureate (malik al-shuʿarāʾ).[5] He died at an old age in 1674[6] or 1683.[7]

Works

Nuṣratī wrote in the Deccani variety of Urdu and Persian.[8] His poetry uses archaic language and a complex style.[2] He was a prominent practitioner of the qaṣīda, ghazal and especially mathnawī forms.[9] One of his earliest works, Miʿrāj-nāma, was written for Sultan Muḥammad ʿĀdil Shāh (r. 1627–1656).[10]

His most original work is the ʿAlī-nāma, an epic celebration of ʿAlī II's wars against the Mughals and Marathas.[11] It is the earliest panegyric of a ruler in Deccani.[4] Nuṣratī himself claimed to have invented a new poetic form with this work, which is "the only thing of its kind in Urdu".[12] It is patterned on the Persian Shāh-nāma.[13] Grahame Bailey calls it the greatest poem ever written at Bījāpūr.[10]

Nuṣratī's final poem, written in a similar vein, is Taʾrīkh-i Sikandarī (also called the Taʾrīkh-i Bahlol Khani), a celebration of Bahlol Khan's victory over Shivaji at the battle of Umrani in 1672. It was written for ʿAlī II's successor, Sikandar.[14] Unlike the ʿAlīnāma, written at the height of Bījāpūr's power, it is "largely in a minor key".[12] Other works of Nuṣratī's include Gulshan-i ʿishq (1658), a collection of odes and the lyric collection Guldasta-yi ʿishq.[15] Gulshan-i ʿishq is a highly conventional romance.[16]

Notes

- Saksena 1990, pp. 39–40. His (nick)name is also spelled "Naṣrat(ī)".

- Haywood 1995.

- Haywood 1995; Zaidi 1993, pp. 42–43.

- Saksena 1990, pp. 39–40.

- Haywood 1995; Sharma 2020, p. 409; Saksena 1990, pp. 39–40.

- Naim 2017; Sharma 2020, p. 402.

- Bailey 1932, pp. 28–29. Zaidi 1993, pp. 42–43, says that he died after the fall of Bījāpūr (1686) and was laureated by Sultan Aurangzeb.

- Sharma 2020, p. 402; Saksena 1990, pp. 39–40.

- Naim 2017; Haywood 1995.

- Bailey 1932, pp. 28–29.

- Haywood 1995; Sharma 2020, p. 409; Dayal 2020, p. 428.

- Sadiq 1995, pp. 55–56.

- Zaidi 1993, pp. 42–43.

- Dayal 2020, p. 428.

- Haywood 1995; Sharma 2020, p. 409; Bailey 1932, pp. 28–29.

- Sadiq 1995, pp. 55–56; Bailey 1932, pp. 28–29.

Works cited

- Bailey, Thomas Grahame (1932). A History of Urdu Literature. Oxford University Press.

- Dayal, Subah (2020). "On Heroes and History: Responding to the Shahnama in the Deccan, 1500–1800". In Overton, Keelan (ed.). Iran and the Deccan: Persianate Art, Culture, and Talent in Circulation, 1400–1700. Indiana University Press. pp. 421–446. ISBN 978-0-253-04894-3.

- Haywood, J. A. (1995). "Nuṣratī". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume VIII: Ned–Sam (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 154. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- Naim, C. M. (2017). "Urdu Poetry". In Greene, Roland (ed.). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (4th ed.). Princeton University Press.

- Sadiq, Muhammad (1995) [1964]. A History of Urdu Literature (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Saksena, Ram Babu (1990) [1927]. A History of Urdu Literature. Asian Educational Services.

- Sharma, Sunil (2020). "Forging a Canon of Dakhni Literature: Translations and Retellings from Persian". In Overton, Keelan (ed.). Iran and the Deccan: Persianate Art, Culture, and Talent in Circulation, 1400–1700. Indiana University Press. pp. 401–420. ISBN 978-0-253-04894-3.

- Zaidi, Ali Jawad (1993). A History of Urdu Literature. Sahitya Akademi.

Further reading

- Abdul Haq, ed. (n.d.). Nusrati: The Poet-Laureate of Bijapur (A Critical Study of his Life and Works) (in Urdu). New Delhi: Anjuman-e-Taraqqi-e-Urdu.

- Haidar, Navina Najat (2014). "Gulshan-I 'Ishq: Sufi Romance of the Deccan". In Parodi, Laura E.; Eaton, Richard M. (eds.). The Visual World of Muslim India: The Art, Culture and Society of the Deccan in the Early Modern Era. London: I. B. Tauris. pp. 295–318. ISBN 978-0-7556-0561-3. OCLC 1128174855.