Nut Island effect

The Nut Island effect describes an organizational behavior phenomenon in which a team of skilled employees becomes isolated from distracted top managers resulting in a catastrophic loss of the ability of the team to perform an important mission. The term was coined by Paul F. Levy, a former Massachusetts state official, in an article in the Harvard Business Review published in 2001. The article outlines a situation which resulted in massive pollution of Boston Harbor, and proposes that the name of the facility involved be applied to similar situations in other business enterprises. The work is used as a source in human resources management case studies and is featured on the websites of several business management consulting firms and health care institutions.

Description

Levy served as executive director of the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) from 1987 to 1992 before writing "The Nut Island Effect: When Good Teams Go Wrong", which describes conditions at the authority's Nut Island sewage treatment facility in Quincy, Massachusetts, over a three decade period ending in the plant's closure in 1997. The article uses the history of the facility to illustrate a five-step process that defines a business scenario that progressively leads to management-employee alienation, employee self-regulation of critical processes and finally catastrophic mission failure. In summary, the steps are:[1]

- Management distraction and team autonomy – A climate exists where management is consumed by other issues and the team is a cohesive unit of highly motivated and skilled individuals who thrive on autonomy and avoid publicity.

- Assumptions and resentment – Management assumes team self-sufficiency and begins to ignore requests for assistance, resulting in team resentment of management.

- De facto separation – The team cohesiveness and resentment of management results in a full separation characterized by limited communication and complete refusal of outside assistance.

- Self-rule – In order to satisfy external requirements the team creates self-imposed regulations which create hidden problems.

- Chronic systemic failure and collapse – Management indifference and misguided team self-regulation become systemic, resulting in repeated failure and eventual catastrophic collapse.

Background

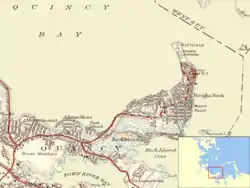

Nut Island is a small roughly 5-acre (0.020 km2) former island in Boston Harbor that was joined by landfill to the Hough's Neck peninsula in northeastern Quincy by the 1940s for use as the site of a sewage treatment facility. The operation of sewage treatment and disposal facilities in populous eastern Massachusetts was the responsibility of an independent state agency known as the Metropolitan District Commission (MDC). The commission, also responsible for the construction and maintenance of several roadways, recreational facilities such as swimming pools and hockey rinks and water distribution infrastructure, became known as fertile ground for political patronage in Massachusetts.[2] As a result, top management became focused on the satisfaction of political goals and constituent recreation requests at the expense of mundane, less visible responsibilities including sewage treatment facilities operations. At the same time, following the end of both World War II and the Korean War, the sewage treatment facility opened in 1952 at Nut Island and was staffed by several ex-service members. By nature of their military experience, this team was both strongly inclined to build a powerfully cohesive unit possessing excellent improvisational skills and was well suited to operating in isolation under adverse conditions.[3]

The management and employee situations satisfied the requirements of step one of Levy's analysis. As time progressed management focused on political issues and became reliant on the quiet, consistent operation of the facility that the workers gladly provided. The plant staff found management to be so trusting and distracted as to provide little or no assistance in the resolution of problems. This resulted in the workers resenting the distant managers and creating a self-sustaining, self-regulating operation that often misreported situations and problems in an effort to both satisfy outside regulators and avoid management entirely. This environment led to staff reliance on unscientific treatment procedures and improvised unorthodox plant operation, primarily to avoid equipment replacement that required management approval. Eventually a series of plant failures culminated in a massive four-day discharge of untreated sewage in January 1976.[4]

Cleanup Efforts

The failures at Nut Island and the companion Deer Island plant adjacent to Winthrop, Massachusetts, had far-reaching environmental and political effects. Fecal coliform bacteria levels forced frequent swimming prohibitions along the harbor beaches and the Charles River for many years.[5] The City of Quincy sued the MDC and the separate Boston Water and Sewer Commission in 1982, charging unchecked systemic pollution of the city's waterfront. That suit was followed by one by the Conservation Law Foundation and finally by the United States Government, resulting in a landmark court-ordered cleanup of Boston Harbor.[6] The lawsuits forced then Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis to propose separating the water and sewer treatment divisions from the MDC, resulting in the creation of the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority in 1985. The slow progress of the cleanup became a central theme of the 1988 U.S. presidential election as George H. W. Bush defeated Dukakis partly through campaign speeches casting doubt on the governor's environmental record, which Dukakis had claimed was better than that of Bush.[7] The court-ordered cleanup continued throughout the next two decades and is still ongoing.[6][8]

Conclusions

Levy became head of the MWRA in 1987 and presided over harbor cleanup and management reforms for the next four-and-a-half years. His experiences with those efforts and dialog with managers and employees at the time and in the following years led to publication of the paper. In the paper Levy provides a brief framework of recommendations for companies that wish to forestall or avert similar communication crises in their organizations. Among his proposed remedies are creation of links between employee actions and external controls with performance-based rewards, constant management presence and communication with remote operations centers and regular turnover of new employees at those centers.[9] The prominence of the Boston Harbor case has led to the paper being featured in human resources curriculums and as a training tool by business consulting firms.[10][11][12]

References

- Levy, p. 8

- Dolin, p. 63

- Levy, pp. 7-9

- Levy, pp. 9-11

- "A Spatial and Temporal Analysis of Boston Harbor Microbiological Data" (PDF). Technical Report No. 91-3. Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. June 1991. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- Mazzone, Hon. A. David. "Mazzone, Judge A. David : Chamber Papers on the Boston Harbor Clean Up Case, 1985-2005". Archived from the original on 2010-06-10. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- Butterfield, Fox (April 6, 1991). "Boston Harbor cleanup haunts a new governor". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- "The Boston Harbor Case". MWRA Online. Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. June 19, 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- Levy, p. 10

- Hackos, PhD, JoAnn (September 2004). "The Nut Island Effect". Center for Information-Development Management. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- Williams, Stephen (May 2007). "Life On Nut Island". The Walrus. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- "Thoughts and Smarts". JICA-MP Reproductive Health Project. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

Sources

- Levy, Paul F. (March 1, 2001). "The Nut Island Effect: When Good Teams Go Wrong". Harvard Business Review. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing. 79 (3): 51–9, 163. PMID 11246924. Retrieved 2015-02-05.

- Dolin, Eric Jay (2004). Political waters: the long, dirty, contentious, incredibly expensive but eventually triumphant history of Boston Harbor--a unique environmental success story. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-1-55849-445-9. Retrieved 2009-06-11.