Nyasaland

Nyasaland Protectorate | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1907–1964 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Status | British protectorate | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Zomba | ||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||

• 1907–1910 | Edward VII | ||||||||||||

• 1910–1936 | George V | ||||||||||||

• 1936 | Edward VIII | ||||||||||||

• 1936–1952 | George VI | ||||||||||||

• 1952–1964 | Elizabeth II | ||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||

• 1907–1908 (first) | William Manning | ||||||||||||

• 1961–1964 (last) | Glyn Smallwood Jones | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Legislative Council | ||||||||||||

| Establishment | |||||||||||||

• Establishment | 6 July 1907 | ||||||||||||

| 1 August 1953 | |||||||||||||

| 31 December 1963 | |||||||||||||

| 6 July 1964 | |||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

• Total | 102,564 km2 (39,600 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1924 census | 6,930,000[1] | ||||||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Malawi | ||||||||||||

Nyasaland (/nɪˈæsəlænd, naɪˈæsə-/[2]) was a British protectorate located in Africa that was established in 1907 when the former British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. Between 1953 and 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. After the Federation was dissolved, Nyasaland became independent from Britain on 6 July 1964 and was renamed Malawi.

Nyasaland's history was marked by the massive loss of African communal lands in the early colonial period. In January 1915, the Reverend John Chilembwe staged an attempt at rebellion in protest at discrimination against Africans. Colonial authorities reassessed some of their policies. From the 1930s, a growing class of educated African elite, many educated in the United Kingdom, became increasingly politically active and vocal about gaining independence. They established associations and, after 1944, the Nyasaland African Congress (NAC).

When Nyasaland was forced in 1953 into a Federation with Southern and Northern Rhodesia, there was a rise in civic unrest, as this was deeply unpopular among the people of the territory. The failure of the NAC to prevent this caused its collapse. Soon, a younger and more militant generation revived the NAC. They invited Hastings Banda to return to the country and lead it to independence as Malawi in 1964.

Historic population

The 1911 census was the first after the protectorate was renamed as Nyasaland. The population according to this census was: Africans, classed as "natives": 969,183, Europeans 766, Asians 481. In March 1920 Europeans numbered 1,015 and Asians 515. The number of Africans was estimated (1919) at 561,600 males and 664,400 females, a total of 1,226,000.[3] Blantyre, the chief town, had some 300 European residents.[3] The number of resident Europeans was always small, only 1,948 in 1945. By 1960 their numbers rose to about 9,500, but they declined afterward following the struggle for independence. The number of ethnic Asian residents, many of whom were traders and merchants, was also small.[4]

The category of 'native' was large, but there was no general definition of the term. In a Nyasaland court case of 1929, the judge opined that, "A native means a native of Africa who is not of European or Asiatic race or origin; all others are non-natives. A person's race or origin does not depend on where he or she is born. Race depends on the blood in one's veins ...".[5] Unlike Europeans of British origin, Nyasaland natives did not hold British citizenship under British nationality law, but had the lesser status of British protected person.[6] The term 'native' was used in all colonial censuses up to and including 1945.

Census data from colonial censuses and the first census after independence in the table below show a population that increased quite rapidly. The de facto populations count those who are resident; the de jure populations include absent migrant workers who gave addresses in Malawi as their permanent home.

| Year | De facto population | De jure population | Annual increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 736,724 | ||

| 1911 | 969,183 | 2.8% | |

| 1921 | 1,199,934 | 2.2% | |

| 1926 | 1,280,885 | 1,290,885 | 1.5% |

| 1931 | 1,569,888 | 1,599,888 | 4.4% |

| 1945 | 2,044,707 | 2,178,013+ | 2.2% |

| 1966 | 4,020,724 | 4,286,724+ | 3.3% |

@derived from the de jure population by subtraction of those known to be abroad.

+derived from the de facto population by addition of those known to be abroad.

Source: Final Report of the 1966 Census of Malawi, Zomba, 1968.

The colonial censuses were imprecise: those of 1901 and 1911 estimated the African population based on hut tax records, and adult male tax defaulters (up to 10% of the total) went unrecorded. The censuses of 1921, 1926 and 1931 did not make individual counts of the African population, probably under-estimated absentees, and under-counted in remote areas.[7] The census of 1945 was better, but still not a true record of the African population. The censuses of 1921, 1931 and 1945 all recorded the numbers of Mozambique immigrants. Those conducted before 1945 may have substantially under-recorded the number of Africans and also the full extent of labour emigration out of Nyasaland.[8]

Throughout the colonial period and up to the present, the rural population density of Nyasaland/Malawi has been among the highest in sub-Saharan Africa. Although the population increased quite rapidly, doubling between 1901 and 1931, high infant mortality and deaths from tropical diseases restricted the natural increase to no more than 1 to 2 percent a year. The rest of the increase seems to have resulted from immigration from Mozambique. From 1931 to 1945, natural increase doubled, probably through improved medical services, and infant mortality gradually decreased. Although immigration continued throughout the colonial period, it was a less significant factor.[9]

The 1921 census listed 108,204 "Anguru" (Lomwe-speaking immigrants from Mozambique). It is likely that a large number of those listed under other tribal names had crossed the border from Mozambique as well. It is also likely that the numbers of immigrants from tribal groups believed to belong to surrounding territories, mainly Mozambique and Northern Rhodesia, had doubled between 1921 and 1931. Most of this large migratory movement took place after 1926. The Anguru population further increased by more than 60 percent between 1931 and 1945. The 1966 census recorded 283,854 foreign-born Africans, of whom about 70 percent were born in Mozambique.[10]

This inward immigration of families was somewhat balanced by outward labour emigration, mainly by men, to Southern Rhodesia and South Africa. The development of Nyasaland was likely adversely affected by the drain of workers to other countries. The Nyasaland government estimated that 58,000 adult males were working outside Nyasaland in 1935. The Southern Rhodesian census of 1931 alone recorded 54,000 male Nyasaland Africans there, so the former estimate was probably undercounting the total number of workers in other countries. In 1937, it was estimated that over 90,000 adult males were migrant workers: of these a quarter was thought not to have been in touch with their families for more than five years.[11]

By 1945 almost 124,000 adult males and almost 9,500 adult females were known to be absent, excluding those who were not in touch with their families.[12] The great bulk of migrant workers came from the rural Northern and Central regions: in 1937, out of 91,000 Africans recorded as absent, fewer than 11,000 were from districts in the south, where there were more jobs available.[13] Labour migration continued up to and after independence. It was estimated that in 1963, some 170,000 men were absent and working abroad: 120,000 in Southern Rhodesia, 30,000 in South Africa, and 20,000 in Zambia.[14]

Administration

Central

.jpg.webp)

Throughout the period 1907 to 1953, Nyasaland was subject to direct superintendence and control by the Colonial Office and the United Kingdom parliament. Its administration was headed by a Governor, appointed by the British Government and responsible to the Colonial Office. As Nyasaland needed financial support through grants and loans, Governors also reported to HM Treasury on financial matters.[15] From 1953 to the end of 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, which was not a fully independent state as it was constitutionally subordinate to the British government. Nyasaland remained a protectorate and its Governors retained responsibilities for local administration, labour and trade unions, African primary and secondary education, African agriculture and forestry, and internal policing.[16]

The greater part of the Governors' former powers was transferred to the Federal government. This had sole responsibility for external affairs, defence, immigration, higher education, transport, posts and major aspects of economic policy, and the predominant role in health, industrial development and electricity. The Colonial Office retained ultimate power over African affairs and the African ownership of land.[16] The Federation was formally dissolved on 31 December 1963; at the same time Nyasaland's independence was fixed for 6 July 1964.[17]

Most governors spent the bulk of their career in other territories but were assisted by heads of departments who spent their working life in Nyasaland. Some of these senior officials also sat on the two councils that advised governors. The Legislative Council was formed solely of officials in 1907 to advise governors on legislation; from 1909 a minority of nominated "non-official" members was added. Until 1961, the Governor had power to veto any ordinance passed by the Legislative Council.[18] The Executive Council was a smaller body advising on policy. It was formed solely of officials until 1949, when two nominated white "non-official" members were added to eight officials.[19][20]

The composition of the Legislative Council gradually became more representative. In 1930, its six "non-official" members were no longer nominated by the governor but were selected by as association representing white planters and businessmen. Until 1949, African interests were represented by one white missionary. That year the governor appointed three Africans and an Asian to join six white "non-official" and 10 official members.

From 1955, its six white "non-official" members were elected; five Africans (but no Asians) were nominated. Only in 1961 were all Legislative Council seats filled by election: the Malawi Congress Party won 22 of 28 seats. The party was also nominated to seven of the 10 Executive Council seats.[21][22]

Local

The protectorate was divided into districts from 1892, with a Collector of Revenue (later called District Commissioner in charge of each. There were originally around a dozen districts, but the number had increased to some two dozen at independence. The 12 Collectors and 26 assistants in 1907 were responsible for collecting Hut tax and customs duties; they also had judicial responsibilities as magistrates, although few had any legal training. From 1920 the District Commissioners reported to three Provincial Commissioners for the Northern, Central and Southern provinces. They, in turn, reported to the Chief Secretary in Zomba. The numbers of District Commissioners and their assistants rose slowly to 51 in 1937 and about 120 in 1961.[23]

In many parts of the protectorate, there were few strong chiefs. At first the British tried to evade the powers of existing chiefs who were powerful, minimising them in favour of direct rule by the Collectors. From 1912, Collectors were able to nominate principal headmen and village headmen as local intermediaries between the protectorate administration and local people, in an early form of Indirect rule. Each Collector could determine what powers to delegate to headmen in his district. Some appointed existing traditional chiefs as Principal headmen, who had significant authority locally.[24]

Another version of indirect rule was instituted in 1933. The government authorized the chiefs and their councils as Native Authorities, but they had few real powers and little money to enforce them.[25][26] The Native Authorities could set up Native Courts to decide cases under local customary law. But Sir Charles Golding, governor from 1924 to 1929, believed that the system of traditional chiefs was in decay and could not be relied on. Native Courts had no jurisdiction over European-owned estates. They were subject to the oversight of District Commissioners, and they were generally used by the colonial administration to enforce unpopular agricultural rules. They dealt with the vast bulk of civil disputes in the protectorate.[27]

From 1902, the British established English law as the official legal code, and set up a High Court on the English model, with a Chief Justice and other judges. Appeals were heard by the East African Appeals Court in Zanzibar. Customary law was allowed (but not mandatory) in cases involving Africans, if native law or custom was not repugnant to English legal principles.[28] Order was at first maintained by soldiers of the King's African Rifles,[3] some of whom were seconded to assist the District Commissioners, or by poorly trained police recruited by the District Commissioners. A better-trained central colonial police force was set up in 1922, but in 1945 it still had only 500 constables.[29]

After the Second World War, the government increased expenditures on the police and expanded its forces into rural areas. A Police Training School was opened in 1952, police man-power increased to 750 by 1959, and new units were set up (the Special Branch and the Police Mobile Force for riot control). These changes proved insufficient when major disturbances took place in 1959, as support began to grow for independence. The government declared a state of emergency, and military forces were brought in from the Rhodesias and Tanganyika. Police manpower was rapidly expanded to about 3,000 through recruiting and training. After the Malawi Congress Party took power in 1962, it inherited a colonial police force of 3,000, including British senior officers.[30]

Land

Private

European acquisition and ownership of large areas of land presented a major social and political problem for the protectorate, as Africans increasingly challenged this takeover of their land. Between 1892 and 1894, 3,705,255 acres, almost 1.5 million hectares or 15% of the total land area of the Protectorate, was alienated as European-owned estates through the colonial grant of Certificates of Claim. Of this, 2,702,379 million acres, over 1 million hectares, in the north of the protectorate had been acquired by the British South Africa Company for its mineral potential; it was never turned into plantations. But much of the remaining land, some 867,000 acres, or over 350,000 hectares of estates, included a large proportion of the best arable lands in the Shire Highlands, which was the most densely populated part of the country and where Africans had relied on subsistence farming.[31]

The first Commissioner of the Protectorate, Sir Harry Johnston, had hoped that the Shire Highlands would become an area for large-scale European settlement. He later considered it was too unhealthy. He acknowledged that it had a large African population who required sufficient land for their own use, although his successors did not share this view.[32] Additional land alienations were much smaller. Around 250,000 acres of former Crown Lands were sold as freehold land or leased, and almost 400,000 acres more, originally in Certificates of Claim, were sold or leased in holdings whose average size was around 1,000 acres. Many of these were smaller farms operated by Europeans who came to Nyasaland after the First World War to grow tobacco.[33][34]

As late as 1920, a Land Commission set up by the Nyasaland authorities proposed further land alienation, to promote the development of small to medium-size European plantations, from the 700,000 acres of Crown Land which it said were available after the present and future needs of the African people were met. This plan was rejected by the Colonial Office.[35]

Much of the best land in the Shire Highlands was alienated to Europeans at the end of the 19th century. Of more than 860,000 acres, over (350,000 hectares) of estates in the Shire Highlands, only a quarter was poor-quality land. The other 660,000 acres were in areas of more fertile soils, which had a total area of some 1.3 million acres in the Shire Highlands. But two large belts, one from Zomba town to Blantyre-Limbe the second from Limbe to Thyolo town, were almost entirely estates. In these two significant areas, Trust land for Africans was rare and consequently overcrowded.[36]

In the early years of the protectorate, little of the land on estates was planted. Settlers wanted labour and encouraged existing African residents to stay on the undeveloped land. According to L. White, by the 1880s, large areas of the Shire Highlands may have become underpopulated through fighting or slave raiding. It was these almost empty and indefensible areas that Europeans claimed in the 1880s and 1890s. Few Africans were resident on estate lands at that time. After Europeans introduced the requirement for rent payments by tenant farmers, many Africans left the estates. Earlier African residents who had fled to more defensible areas usually avoided returning to settle on estates.[37][38]

New workers (often the so-called "Anguru" migrants from Mozambique) were encouraged to move onto estates and grow their own crops but were required to pay rent. In the early years, this was usually satisfied by two months' labour annually, under the system known as thangata. Later, many owners required a longer period of labour to pay the "rent."[39][40] In 1911 it was estimated that about 9% of the protectorate's Africans lived on estates: in 1945, it was about 10%. These estates comprised 5% of the country by area, but about 15% of the total cultivable land. Estates appeared to have rather low populations relative to the quality of their land.[41][42]

Three major estate companies retained landholdings in the Shire Highlands. The British Central Africa Company once owned 350,000 acres, but before 1928 it had sold or leased 50,000 acres. It retained two large blocks of land, each around 100,000 acres, in the Shire Highlands. The rest of its properties were in or near to the Shire valley. From the late 1920s, it obtained cash rents from African tenants on crowded and unsupervised estates. A L Bruce Estates Ltd owned 160,000 acres, mostly in the single Magomero estate in Zomba, and Chiradzulu districts. Before the 1940s, it had sold little of its land and preferred to farm it directly; by 1948 the estate was largely let to tenants, who produced all its crops. Blantyre and East Africa Ltd had once owned 157,000 acres in Blantyre and Zomba districts, but sales to small planters reduced this to 91,500 acres by 1925. Until around 1930, it marketed its tenants' crops, but after this sought cash rents.[43][44][45]

The 1920 Land Commission also considered the situation of Africans living on private estates and proposed to give all tenants some security of tenure. Apart from the elderly or widows, all tenants would pay rents in cash by labour or by selling crops to the owner, but rent levels would be regulated. These proposals were enacted in 1928 after a 1926 census had shown that over 115,000 Africans (10% of the population) lived on estates.[46][47]

Before 1928, the prevailing annual rent was 6 shillings (30 pence). After 1928, maximum cash rents were fixed at £1 for a plot of 8 acres, although some estates charged less. The "equivalent" rents in kind required delivering crops worth between 30 and 50 shillings instead of £1 cash, to discourage this option. Estate owners could expel up to 10% of their tenants every five years without showing any cause, and could expel male children of residents at age 16, and refuse to allow settlement to husbands of residents' daughters. The aim was to prevent overcrowding, but there was little land available to resettle those expelled. From 1943, evictions were resisted.[48]

Native Trust

British legislation of 1902 treated all the land in Nyasaland not already granted as freehold as Crown Land, which could be alienated regardless of its residents' wishes. Only in 1904 did the Governor receive powers to reserve areas of Crown Land (called Native Trust Land) for the benefit of African communities, and it was not until 1936 that all conversion of Native Trust Land to freehold was prohibited by the 1936 Native Trust Lands Order. The aims of this legislation were to reassure the African people of their rights in land and to relieve them of fears of its alienation without their consent.[49][50] Reassurance was needed, because in 1920 when Native Trust Land covered 6.6 million acres, a debate developed about the respective needs of European and African communities for land. The protectorate administration suggested that, although the African population might double in 30 years, it would still be possible to form new estates outside the Shire Highlands.[51]

Throughout the whole protectorate, the vast majority of its people were rural rather than urban dwellers and over 90% of the rural African population lived on Crown Lands (including the reserves). Their access to land for farming was governed by customary law. This varied, but generally entitled a person granted or inheriting the use of land (not its ownership) the exclusive right to farm it for an indefinite period, with the right to pass it to their successors, unless it was forfeited for a crime, neglect or abandonment. There was an expectation that community leaders would allocate communal land to the community members, but limit its allocation to outsiders. Customary law had little legal status in the early colonial period and little recognition or protection was given to customary land or the communities that used it then.[52][53]

It has been claimed that throughout the colonial period and up to 1982 Malawi had sufficient arable land to meet the basic food needs of its population, if the arable land were distributed equally and used to produce food.[54] As early as 1920, while the Land Commission did not consider that the country was inherently overcrowded, it noted that, in congested districts where a large proportion of the working population was employed, particularly on tea estates or near towns, families had only 1 to 2 acres to farm.[55] By 1946, the congested districts were even more crowded.[56]

Reform

From 1938, the protectorate administration began to purchase small amounts of under-used estate land for resettlement of those evicted. These purchases were insufficient and, in 1942, hundreds of Africans in the Blantyre District who had been served with notices to quit refused to leave since there was no other land for them. Two years later the same difficulty arose in the densely populated Cholo District, two-thirds of whose land constituted private estates.[57]

In 1946 the Nyasaland government appointed a commission, the Abrahams Commission (also known the Land Commission) to inquire into land issues following the riots and disturbances by tenants on European-owned estates in 1943 and 1945. It had only one member, Sir Sidney Abrahams, who proposed that the Nyasaland government should purchase all unused or under-used freehold land on European-owned estates which would become Crown land, available to African farmers. The Africans on estates were to be offered the choice of remaining on the estate as workers or tenants or of moving to Crown land. These proposals were not implemented in full until 1952.[58]

The report of the Abrahams Commission divided opinion. Africans were generally in favour of its proposals, as was the governor from 1942 to 1947, Edmund Richards (who had proposed the establishment of a Land Commission) and the incoming governor, Geoffrey Colby. Estate owners and managers were strongly against it, and many European settlers bitterly attacked it.[59]

As a result of the Abrahams report, in 1947 the Nyasaland government set up a Land Planning Committee of civil servants to advise on implementing its proposals and deal with the acquisition of land for resettlement. It recommended the re-acquisition only of land which was either undeveloped or occupied by large numbers of African residents or tenants. Land capable of future development as estates was to be protected against unorganised cultivation.[60] From 1948, the programme of land acquisition intensified, assisted by an increased willingness of estate owners who saw no future in merely leasing land and marketing their tenants' crops. In 1948, it was estimated that 1.2 million acres (or 487,000 hectares) of freehold estates remained, with an African population of 200,000. At independence in 1964, only some 422,000 acres (171,000 hectares) of European-owned estates remained, mainly as tea estates or small estates farmed directly by their owners.[61][62]

Agricultural economy

Although Nyasaland has some mineral resources, particularly coal, these were not exploited in colonial times.[63] Without economic mineral resources, the protectorate's economy had to be based on agriculture, but in 1907 most of its people were subsistence farmers. In the mid-to-late 19th century, cassava, rice, beans and millet were grown in the Shire Valley, maize, cassava, sweet potatoes and sorghum in the Shire Highlands, and cassava, millet and groundnuts along the shores of Lake Nyasa (now Lake Malawi). These crops continued to be staple foods throughout the colonial period, although with less millet and more maize. Tobacco and a local variety of cotton were grown widely.[64]

Throughout the protectorate, the colonial Department of Agriculture favoured European planter interests. Its negative opinion of African agriculture, which it failed to promote, helped to prevent the creation of a properly functioning peasant economy.[65][66] It criticised the practice of shifting cultivation in which trees on the land to be cultivated were cut down and burnt and their ashes dug into the soil to fertilise it. The land was used for a few years after another section of land was cleared.[67]

Compared with European, North American and Asian soils many sub-Saharan African soils are low in natural fertility, being poor in nutrients, low in organic matter and liable to erosion. The best cultivation technique for such soils involves 10 to 15 years of fallow between 2 or 3 years of cultivation, the system of shifting cultivation and fallowing that was common in Nyasaland as long as there was sufficient land to practice it. As more intensive agricultural use began in the 1930s, the amounts and duration of fallow were progressively reduced in more populous areas, which placed soil fertility under gradually increasing pressure.[68][69] The Department of Agriculture's prediction that soil fertility would decline at a rapid rate is contradicted by recent research. This showed that the majority of soils in Malawi were adequate for smallholders to produce maize. Most have sufficient (if barely so) organic material and nutrients, although their low nitrogen and phosphorus favours the use of chemical fertilisers and manure.[70]

Although in the early years of the 20th century European estates produced the bulk of exportable cash crops directly, by the 1930s, a large proportion of many of these crops (particularly tobacco) was produced by Africans, either as smallholders on Crown land or as tenants on the estates. The first estate crop was coffee, grown commercially in quantity from around 1895, but competition from Brazil which flooded the world markets by 1905 and droughts led to its decline in favour of tobacco and cotton. Both these crops had previously been grown in small quantities, but the decline of coffee prompted planters to turn to tobacco in the Shire Highlands and cotton in the Shire Valley.[71]

Tea was also first planted commercially in 1905 in the Shire Highlands, with significant development of tobacco and tea growing taking place after the opening of the Shire Highlands Railway in 1908. During the 56 years that the protectorate existed, tobacco, tea and cotton were the main export crops, and tea was the only one that remained an estate crop throughout.[71] The main barriers to increasing exports were the high costs of transport from Nyasaland to the coast, the poor quality of much of the produce and, for African farmers, the planters' opposition to them growing cotton or tobacco in competition with the estates.[72]

Crops

The areas of flue-cured brightleaf or Virginia tobacco farmed by European planters in the Shire Highlands rose from 4,500 acres in 1911 to 14,200 acres in 1920, yielding 2,500 ton of tobacco. Before 1920, about 5% of the crop sold was dark-fired tobacco produced by African farmers, and this rose to 14% by 1924. The First World War boosted the production of tobacco, but post-war competition from United States Virginia required a rebate of import duty under Imperial Preference to assist Nyasaland growers.[73]

Much of the tobacco produced by the European estates was of low-grade. In 1921, 1,500 tons of a 3,500-ton crop was saleable and many smaller European growers went out of business. Between 1919 and 1935 their numbers fell from 229 to 82. The decline in flue-cured tobacco intensified throughout the 1920s. Europeans produced 86% of Malawi's tobacco in 1924, 57% in 1927, 28% in 1933, and 16% in 1936. Despite this decline, tobacco accounted for 65–80% of exports from 1921 to 1932.[74][75]

Formation of a Native Tobacco Board in 1926 stimulated the production of fire-cured tobacco. By 1935, 70% of the national tobacco crop was grown in the Central Province where the Board had around 30,000 registered growers. At first, these farmed Crown land, but later estates contracted sharecropping "Visiting Tenants". The number of growers fluctuated until the Second World War then expanded, so by 1950 there were over 104,500 growers planting 132,000 acres and growing 10,000 tons of tobacco. 15,000 were growers in the Southern Province. About three-quarters were smallholders on Native Trust Land, the rest estate tenants. Numbers declined later, but there were still 70,000 in 1965, producing 12,000 tons. Although the value of tobacco exports continued to rise, they decreased as a proportion of the total after 1935 because of the increased importance of tea.[76][77][78]

Egyptian cotton was first grown commercially by African smallholders in the upper Shire valley in 1903 and spread to the lower Shire valley and the shores of Lake Nyasa. By 1905 American Upland cotton was grown on estates in the Shire Highlands. African-grown cotton was bought by British Central Africa Company and the African Lakes Corporation until 1912 when government cotton markets were established where a fairer price for cotton was given.[79]

Reckless opening-up of unsuitable land by inexperienced planters had led to 22,000 acres of cotton in 1905, but 140 tons were exported. Halving of the area to 10,000 acres and improving quality made cotton more important, to a peak of 44% of export value in 1917 when the First World War stimulated demand to 1,750 tons. A shortage of manpower and disastrous floods in the lower Shire valley caused a drop in production to 365 tons in 1918. It was not until 1924 that the industry recovered, reaching 2,700 tons in 1932 and a record of 4,000 tons exported in 1935. This was mainly African production in the lower Shire valley, as output from European estates became insignificant. The relative importance of cotton exports dropped from 16% of the total in 1922 to 5% in 1932, then rallied to 10% in 1941, falling to 7% in 1951. The quality of cotton produced improved from the 1950s with stricter controls on pests and, although 80% of the crop continued to be grown in the lower Shire valley, it also began to be grown in the northern shore of Lake Malawi. Production varied widely, and increasing amounts were used domestically, but at independence cotton was only the fourth most valuable export crop.[80][81]

Tea was first exported from Nyasaland in 1904 after tea plantations were established in the high rainfall areas of Mlanje District, later extended into Cholo District. Exports steadily increased from 375 tons in 1922 to 1,250 tons in 1932, from 12,600 acres planted. The importance of tea increased dramatically after 1934, from only 6% of total exports in 1932 to over 20% in 1935. It never fell below that level, rising to over 40% from 1938 to 1942, and in the three years 1955, 1957 and 1960 the value of tea exports exceeded that of tobacco and until the mid-1960s, Nyasaland had the most extensive area of tea cultivation in Africa. Despite its value to the protectorate's economy, the main problem with its tea on the international market was its low quality.[82][83]

Groundnut exports were insignificant before 1951 when they amounted to 316 tons, but a government scheme to promote their cultivation and better prices led to a rapid increase in the mid-to-late 1950s. At independence, the annual exports totalled 25,000 tons and groundnuts became Nyasaland's third most valuable export. They are also widely grown for food. In the 1930s and 1940s, Nyasaland became a major producer of tung oil and over 20,000 acres on estates in the Shire Highlands were planted with tung trees. After 1953, world prices declined and production dropped as tung oil was replaced by cheaper petrochemical substitutes. Until the 1949 famine, maize was not exported but a government scheme then promoted it as a cash crop, and 38,500 tons were exported in 1955. By independence, local demand had reduced exports to virtually nil.[84]

Hunger and famine

Seasonal hunger was common in pre-colonial and early colonial times, as peasant farmers grew food for their families' needs, with only small surpluses to store, barter for livestock or pass to dependents. Famines were often associated with warfare, as in a major famine in the south of the country in 1863.[85][86] One theory of colonial-era African famines is that colonialism led to poverty by expropriating land for cash crops or forcing farmers to grow them (reducing their ability to produce food), underpaying for their crops, charging rents for expropriated lands and taxing them arbitrarily (reducing their ability to buy food). The introduction of a market economy eroded several pre-colonial survival strategies such as growing secondary crops in case the main one failed, gathering wild food or seeking support from family or friends and eventually created an underclass of the chronically malnourished poor.[87]

Nyasaland suffered local famines in 1918 and at various times between 1920 and 1924, and significant food shortages in other years. The government took little action until the situation was critical when relief supplies were expensive and their distribution delayed and was also reluctant to issue free relief to the able-bodied. It imported around 2,000 tons of maize for famine relief in 1922 and 1923 and buy grain in less-affected areas. Although these events were on a smaller scale than in 1949, the authorities did not react by making adequate preparations to counteract later famines.[88][89]

In November and December 1949, the rains stopped several months early and food shortages rapidly developed in the Shire Highlands. Government and mission employees, many urban workers and some estate tenants received free or subsidised food or food on credit. Those less able to cope, such as widows or deserted wives, the old, the very young and those already in poverty suffered most, and families did not help remoter relatives. In 1949 and 1950, 25,000 tons of food were imported, although initial deliveries were delayed. The official mortality figure was 100 to 200 deaths, but the true number may have been higher, and there were severe food shortages and hunger in 1949 and 1950.[90][91][92]

Transport

From the time of Livingstone's expedition in 1859, the Zambesi, Shire River, and Lake Nyasa waterways were seen as the most convenient method of transport for Nyasaland. The Zambesi-Lower Shire and Upper Shire-Lake Nyasa systems were separated by 80 kilometres (50 mi) of impassable falls and rapids in the Middle Shire which prevented continuous navigation. The main economic centres of the protectorate at Blantyre and in the Shire Highlands were 40 km (25 mi) from the Shire, and transport of goods from that river was by inefficient and costly head porterage or ox-cart. Until 1914, small river steamers carrying 100 tons or less operated between the British concession of Chinde at the mouth of the Zambezi and the Lower Shire, about 290 km (180 mi). The British government had obtained a 99-year lease of a site for an ocean port at Chinde at which passengers transferred to river steamers from Union-Castle Line and German East Africa Line ships up to 1914, when the service was suspended. The Union-Castle service was resumed between 1918 and 1922 when the port at Chinde was damaged by a cyclone.[93]

Until the opening of the railway in 1907, passengers and goods were transferred to smaller boats at Chiromo to go a further 80 kilometres (50 mi) upstream to Chikwawa, where porters carried goods up the escarpment and passengers continued on foot. Low water levels in Lake Nyasa reduced the Shire River's flow from 1896 to 1934; this and the changing sandbanks made navigation difficult in the dry season. The main port moved downriver from Chiromo to Port Herald in 1908, but by 1912 it was difficult and often impossible to use Port Herald, so a Zambezi port was needed. The extension of the railway to the Zambezi in 1914 effectively ended significant water transport on the Lower Shire, and low water levels ended it on the Upper Shire, but it has continued on Lake Nyasa up to the present.[94][95]

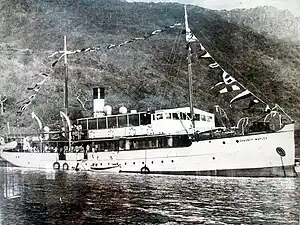

A number of lake steamers, at first based at Fort Johnston, served lakeside communities which had poor road connections. Their value was increased in 1935 when a northern extension of the railway from Blantyre reached Lake Nyasa, and a terminal for Lake Services was developed at Salima. Harbour facilities at several lake ports were inadequate and there were few good roads to most ports: some in the north had no road connection.[96][97]

Railways could supplement water transport and, as Nyasaland was nowhere closer than 320 km (200 mi) to a suitable Indian Ocean port, a short rail link to river ports that eliminated porterage was initially more practical than a line direct to the coast passing through low-population areas. The Shire Highlands Railway opened a line from Blantyre to Chiromo in 1907 and extended it to Port Herald, 182 km (113 mi) from Blantyre in 1908. After Port Herald became unsatisfactory, the British South Africa Company built the Central African Railway, mainly in Mozambique, of 98 km (61 mi) from Port Herald to Chindio on the north bank of the Zambezi in 1914. From here, goods went by river steamers to Chinde then by sea to Beira, involving three transhipments and delays. The Central African Railway was poorly built and soon needed extensive repairs.[98]

Chinde was severely damaged by a cyclone in 1922 and was unsuitable for larger ships. The alternative ports were Beira, which had developed as a major port in the early 20th century, and the small port of Quelimane. Beira was congested, but significant improvements were made to it in the 1920s: the route to Quelimane was shorter, but the port was underdeveloped. The Trans-Zambezia Railway, constructed between 1919 and 1922, ran 269 km (167 mi) from the south bank of the Zambezi to join the main line from Beira to Rhodesia. Its promoters had interests in Beira port, and they ignored its high cost and limited benefit to Nyasaland of a shorter alternative route.[99][100]

The Zambezi crossing ferry, using steamers to tow barges, had limited capacity and was a weak point in the link to Beira. For part of the year the river was too shallow and at other times it flooded. In 1935, the ferry was replaced by construction of the Zambezi Bridge, over three kilometres (2 mi) long, creating an uninterrupted rail link to the sea. In the same year, a northern extension from Blantyre to Lake Nyasa was completed.[101][102]

The Zambezi Bridge and northern extension generated less traffic than anticipated, and it was only in 1946 that traffic volumes predicted in 1937 were reached. The rail link was inadequate for heavy loads, being a single narrow-gauge track with sharp curves and steep gradients. Maintenance costs were high and freight volumes were low, so transport rates were up to three times Rhodesian and East African levels. Although costly and inefficient, the rail link to Beira remained Nyasaland's main transport link up to and beyond independence. A second rail link to the Mozambique port of Nacala was first proposed in 1964 and is the principal route for imports and exports today.[103][104]

Roads in the early protectorate were little more than trails, barely passable in the wet season. Roads suitable for motor vehicles were developed in the southern half of the protectorate in the 1920s and replaced head porterage, but few all-weather roads existed in the northern half until quite late in the 1930s, so motor transport was concentrated in the south. Road travel was becoming an alternative to rail, but government regulations designed to promote railway use hindered this development. When the northern railway extension was completed, proposals failed to be carried out to build a road traffic interchange at Salima and improve roads in the Central Province to help develop Central Nyasaland and Eastern Zambia. Road transport remained underdeveloped and, at independence, there were few tarmac roads.[105][106]

Air transport began modestly in 1934 with weekly Rhodesian and Nyasaland Airways service from an airstrip at Chileka to Salisbury, increased to twice weekly in 1937. Blantyre (Chileka) was also linked to Beira from 1935. All flights were discontinued in 1940 but in 1946 Central African Airways Corporation, backed by the governments of Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland resumed services. Its Salisbury to Blantyre service was extended to Nairobi, a Blantyre-Lilongwe-Lusaka service was added and internal services ran to Salima and Karonga. The former Nyasaland arm of the corporation became Air Malawi in 1964.[107][108]

Nationalism

The first protests against colonial rule came from two sources. Firstly, independent African churches rejected European missionary control and, through Watch Tower and other groups, promoted Millennialism doctrines that the authorities considered seditious. Secondly, Africans educated by missions or abroad sought social, economic and political advancement through voluntary "Native Associations". Both movements were generally peaceful, but a violent uprising in 1915 by John Chilembwe expressed both religious radicalism and the frustration of educated Africans denied an effective voice, as well as anger over African casualties in the First World War.[109][110]

After Chilembwe's uprising, protests were muted until the early 1930s and concentrated on improving African education and agriculture. Political representation was a distant aspiration. A 1930 declaration by the British government that white settlers north of the Zambezi could not form minority governments dominating Africans stimulated the political awareness.[111]

Agitation by the government of Southern Rhodesia led to a Royal Commission on future association between Northern and Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, or all three territories. Despite almost unanimous African opposition to amalgamation with Southern Rhodesia, the Bledisloe Commission report of 1939 did not entirely rule out some form of association in the future, provided Southern Rhodesian forms of racial discrimination were not applied north of the Zambezi.[112][113]

The danger of Southern Rhodesian rule made African demands for political rights more urgent, and in 1944 various local Voluntary Associations united as the Nyasaland African Congress (NAC). One of its first demands was to have African representation on the Legislative Council, which was conceded in 1949.[114] From 1946, the NAC received financial and political support from Hastings Banda, then living in Britain. Despite this support, Congress lost momentum until the revival of amalgamation proposals in 1948 gave it new life.[115]

Post-war British governments were persuaded that closer association in Central Africa would cut costs, and they agreed to a federal solution, not the full amalgamation that the Southern Rhodesian government preferred. The main African objections to the Federation were summed up in a joint memorandum prepared by Hastings Banda for Nyasaland and Harry Nkumbula for Northern Rhodesia in 1951. These were that political domination by the white minority of Southern Rhodesia would prevent greater African political participation and that control by Southern Rhodesian politicians would lead to an extension of racial discrimination and segregation.[116][117]

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was pushed through in 1953 against very strong African opposition including riots and deaths in Cholo District although there were also local land issues. In 1953, the NAC opposed federation and demanded independence. Its supporters demonstrated against taxes and pass laws. In early 1954, Congress abandoned its campaign and lost much of its support.[116][117] Shortly after its formation, the Federal government attempted to take control of African affairs from the British Colonial Office. It also scaled-back the fairly modest British post-war development proposals.[118][119]

In 1955, the Colonial Office agreed to the suggestion of the governor of Nyasaland that African representation on the Legislative Council should be increased from three to five members, and that the African members should no longer be appointed by the governor, but nominated by Provincial Councils. As these Provincial Councils were receptive to popular wishes, this allowed these Councils to nominate Congress members to the Legislative Council. This occurred in 1956 when Henry Chipembere and Kanyama Chiume, two young radical members of Congress, were nominated together with three moderates, including two Congress supporters. This success led to a rapid growth in Congress membership in 1956 and 1957.[120]

Several of the younger members of the Nyasaland African Congress had little faith in the ability of its leader, T D T Banda, who they also accused of dishonesty, and wished to replace him with Dr Hastings Banda, then living in the Gold Coast. Dr Banda announced he would only return if given the presidency of Congress. After this was agreed he returned to Nyasaland in July 1958 and T D T Banda was ousted.[121]

Independence

Banda and Congress Party leaders started a campaign of direct action against federation, for immediate constitutional change and eventual independence. As this included resistance to Federal directives on farming practices, protests were widespread and sometimes violent. In January 1958, Banda presented Congress proposals for constitutional reform to the governor, Sir Robert Armitage. These were for an African majority in the Legislative Council and at least parity with non-Africans in the Executive Council.[122][123]

The governor rejected the proposals, and this breakdown in constitutional talks led to demands within Congress for an escalation of anti-government protests and more violent action. As Congress supporters became more violent and Congress leaders made increasingly inflammatory statements, Armitage decided against offering concessions but prepared for mass arrests. On 21 February, European troops of the Rhodesia Regiment were flown into Nyasaland and, in the days immediately following, police or troops opened fire on rioters in several places, leading to four deaths.[122][123]

In deciding to make widespread arrests covering almost the whole Congress organisation, Armitage was influenced by a report received by the police from an informer of a meeting of Congress leaders at which, it was claimed by the Head of Special Branch that the indiscriminate killing of Europeans and Asians, and of those Africans opposed to Congress was planned, the so-called "murder plot". There is no evidence that any formal plan existed, and the Nyasaland government took no immediate action against Banda or other Congress leaders but continued to negotiate with them until late February.[124]

In the debate in the House of Commons on 3 March 1959, the day that the State of Emergency was declared, Alan Lennox-Boyd, the Colonial Secretary, stated that it was clear from information received that Congress had planned the widespread murder of Europeans, Asians and moderate Africans, "... in fact, a massacre was being planned". This was the first public mention of a murder plot and, later in the same debate, the Minister of State at the Colonial Office, Julian Amery, reinforced what Lennox-Boyd had said with talk of a "... conspiracy of murder" and "a massacre ... on a Kenyan scale".[125]

The strongest criticism later made by the Devlin Commission was over the "murder plot", whose existence it doubted, and it condemned the use made of it by both the Nyasaland and British governments in trying to justify the Emergency, while at the same time conceding that the declaration of a State of Emergency was "justified in any event". The commission also declared that Banda had no knowledge of the inflammatory talk of some Congress activists about attacking Europeans.[126][127]

On 3 March 1959 Sir Robert Armitage, as governor of Nyasaland, declared a State of Emergency over the whole of the protectorate and, in a police and military undertaking which it called Operation Sunrise arrested Dr. Hastings Banda its president and other members of its executive committee, as well as over a hundred local party officials. The Nyasaland African Congress was banned the next day. Those arrested were detained without trial, and the total number detained finally rose to over 1,300.[128] Over 2,000 more were imprisoned for offences related to the emergency, including rioting and criminal damage. The stated aim of these measures was to allow the Nyasaland government to restore law and order after the increasing lawlessness following Dr Banda's return. Rather than calming the situation immediately, in the emergency that followed fifty-one Africans were killed and many more were wounded.[128]

Of these, 20 were killed at Nkhata Bay where those detained in the Northern Region were being held prior to being transferred south. A local Congress leader encouraged a large crowd to gather, apparently to secure the release of the detainees. Troops who should have arrived in the town early on 3 March were delayed and, when they arrived, the District Commissioner, who felt the situation was out of control ordered them to open fire. Twelve more deaths occurred up to 19 March, mostly when soldiers of the Royal Rhodesia Regiment or Kings African Rifles opened fire on rioters. The remainder of the 51 officially recorded deaths were in military operations in the Northern Region. The NAC, which was banned in 1958 was re-formed as the Malawi Congress Party in 1959.[129][130]

After the emergency, a commission headed by Lord Devlin exposed the failings of the Nyasaland administration. The Commission found that the declaration of a State of Emergency was necessary to restore order and prevent a descent into anarchy, but it criticised instances of the illegal use of force by the police and troops, including burning houses, destroying property and beatings. It rejected the existence of any "murder plot", but noted:

We have found that violent action was to be adopted as a policy, that breaches of the law were to be committed and that attempts by the Government to enforce it were to be resisted with violence. We have found further that there was talk of beating and killing Europeans, but not of cold-blooded assassination or murder.

The report concluded that the Nyasaland administration had lost the support of Nyasaland's African people, noting their almost universal rejection of Federation. Finally, it suggested that the British government should negotiate with African leaders on the country's constitutional future.[126][127] The Devlin Commission's report is the only example of a British judge examining whether the actions of a colonial administration in suppressing dissent were appropriate. Devlin's conclusions that excessive force was used and that Nyasaland was a "police state" caused political uproar. His report was largely rejected and the state of emergency lasted until June 1960.[131]

At first, the British government tried to calm the situation by nominating additional African members (who were not Malawi Congress Party supporters) to the Legislative Council.[132] It soon decided that the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland could not be maintained. It was formally dissolved on 31 December 1963 but had ceased to be relevant to Nyasaland sometime before this. It also decided that Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia should be given responsible government under majority rule. Banda was released in April 1960 and invited to London to discuss proposals for responsible government.[133]

Following the Malawi Congress Party's overwhelming victory in August 1961 elections, Banda and four other Malawi Congress Party members or supporters joined the Executive Council as elected ministers alongside five officials. After a constitutional conference in London in 1962, Nyasaland achieved internal self-government with Banda as Prime Minister in February 1963. Full independence was achieved on 6 July 1964 with Banda as Prime Minister, and the country became the Republic of Malawi, a republic within the Commonwealth, on 6 July 1966, with Banda as president.[134]

Administrative history

From 1953 to 1964 Nyasaland was united with Northern Rhodesia and Southern Rhodesia in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

List of governors

- Sir William Henry Manning: October 1907 – 1 May 1908

- Sir Alfred Sharpe: 1 May 1908 – 1 April 1910

- Francis Barrow Pearce: 1 April 1910 – 4 July 1910

- Henry Richard Wallis: 4 July 1910 – 6 February 1911

- Sir William Henry Manning: 6 February 1911 – 23 September 1913

- George Smith: 23 September 1913 – 12 April 1923

- Richard Sims Donkin Rankine: 12 April 1923 – 27 March 1924

- Sir Charles Calvert Bowring: 27 March 1924 – 30 May 1929

- Wilfred Bennett Davidson-Houston: 30 May 1929 – 7 November 1929

- Shenton Whitelegge Thomas: 7 November 1929 – 22 November 1932

- Sir Hubert Winthrop Young: 22 November 1932 – 9 April 1934

- Kenneth Lambert Hall: 9 April 1934 – 21 September 1934

- Sir Harold Baxter Kittermaster: 21 September 1934 – 20 March 1939

- Sir Henry C. D. Cleveland Mackenzie-Kennedy: 20 March 1939 – 8 August 1942

- Sir Edmund Charles Smith Richards: 8 August 1942 – 27 March 1947

- Geoffrey Francis Taylor Colby: 30 March 1948 – 10 April 1956

- Sir Robert Perceval Armitage: 10 April 1956 – 10 April 1961

- Sir Glyn Smallwood Jones: 10 April 1961 – 6 July 1964

List of chief justices

- Claud Ramsay Wilmot Seton: (c. 1941–1944)

- Sir Edward Enoch Jenkins: (8 Nov 1944–1953)

- Sir Ronald Ormiston Sinclair: (1953–1956) (later Chief Justice of Kenya, 1957)

- Sir Edgar Unsworth: (1962–1964)

- 1964 Nyasaland became independent and was renamed Malawi

List of attorneys general

- Robert William Lyall-Grant (1909–1914) (Attorney General of Kenya, 1920)

- Alan Frederick Hogg (1914–1918)

- Edward St. John Jackson (1918–1920) (Attorney General of Ceylon, 1929)

- Charles Frederic Belcher (1920–1923) (later Chief Justice of Cyprus, 1927)

- Philip Bertie Petrides (1924–1926) (Chief Justice of Mauritius, 1930)

- Kenneth O'Connor (1943–1945) (Attorney General of Malayan Union, 1946)

- Ralph Malcolm Macdonald King (1957–1961)

Notable people born in Nyasaland

- Patrick Allen (1927–2006), British actor

- Michael Green (born 1929- 1 October 2022), British painter and sculptor

- Tony Bird (1945–2019), South African folk rock singer-songwriter

- Kit Hesketh-Harvey (born 1957 - 1st February 2023), British musical performer, translator, composer and screenwriter

- Michelle Paver (born 1960), British novelist and children's writer

- Sir John Welleseley Gunston, 3rd Baronet of Wickwar (born 1962), photographer in Afghanistan in the 1980s

See also

References

- "The British Empire in 1924". The British Empire. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- "Nyasaland definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Cana, Frank Richardson (1922). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 31 (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company. pp. 1165–1166.

- J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, London: Pall Mall Press, pp. 25–26.

- C Joon-Hai Lee, (2005). "The 'Native' Undefined: Colonial Categories, Anglo-African Status and the Politics of Kinship in British Central Africa, 1929–38," The Journal of African History, Vol. 46, No. 3 p. 456.

- C Joon-Hai Lee, (2005). The 'Native' Undefined: Colonial Categories, Anglo-African Status and the Politics of Kinship in British Central Africa, p. 465.

- R Kuczynski, (1949). Demographic Survey of the British Colonial Empire, Volume II, London, Oxford University Press pp. 524–8, 533–9, 579, 630–5.

- Nyasaland Superintendent of the Census, (1946). Report on the Census, 1945, Zomba: Government Printer, pp. 15–17

- R. I. Rotberg, (2000). "The African Population of Malawi: An Analysis of the Censuses between 1901 and 1966" by G Coleman, The Society of Malawi Journal Volume 53, Nos. 1/2, pp.108–9.

- R. I. Rotberg, (2000). The African Population of Malawi, pp.111–15, 117–19.

- UK Government, (1938). Report of the Commission appointed to enquire into the Financial Position and Further Development of Nyasaland, London: HMSO, 1937, p. 96.

- Nyasaland Superintendent of the Census, (1946). Report on the Census, 1945, p.6.

- R Kuczynski, (1949). Demographic Survey of the British Colonial Empire, pp 569–71.

- J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, p. 25.

- G. H. Baxter and P. W. Hodgens, (1957). The Constitutional Status of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, International Affairs, Vol. 33, No. 4, pp. 442, 447

- C. G. Rosberg Jnr. (1956). The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland: Problems of Democratic Government, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 306, p. 99.

- J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, p. 159.

- Z. Kadzimira (1971), Constitutional Changes in Malawi, 1891–1965, Zomba, University of Malawi History Conference 1967, pp. 82–3

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa : The Making of Malawi and Zambia, 1873–1964, Cambridge (Mass), Harvard University Press, pp. 26, 101, 192.

- J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966 Woodbridge, James Currey pp. 234, 271–4, 281. ISBN 978-1-84701-050-6.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 101–2, 269–70, 312–3.

- J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 281–283, 365.

- J McCraken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 70, 217–9.

- J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 72–3.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 22–3, 48–50.

- A C Ross, (2009). Colonialism to Cabinet Crisis: A Political History of Malawi, African Books Collective, pp. 19–21. ISBN 978-99908-87-75-4

- J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 222–3, 226–8.

- Z. Kadzimira (1971), Constitutional Changes in Malawi, 1891–1965, p. 82.

- J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 66, 145, 242.

- M. Deflem, "Law Enforcement in British Colonial Africa", Blog, August 1994 http://deflem.blogspot.co.uk/1994/08/law-enforcement-in-british-colonial.html

- B. Pachai, (1978). Land and Politics in Malawi 1875–1975, Kingston (Ontario): The Limestone Press, pp. 36–7

- J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp. 92–93.

- B. Pachai, (1978). Land and Politics in Malawi 1875–1975, pp.37–41, Kingston (Ontario): The Limestone Press

- R Palmer, (1985). "White Farmers in Malawi: Before and After the Depression", African Affairs Vol. 84 No.335, pp. 237, 242–243.

- Nyasaland Protectorate, (I920) Report of a Commission to enquire into and report upon certain matters connected with the occupation of land in the Nyasaland Protectorate, Zomba: Government Printer, pp. 33–4, 88.

- D Hirschmann and M Vaughan, (1984). Women Farmers of Malawi: Food Production in the Zomba District, Berkeley: University of California, 1984, p. 9.

- R I Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, p.18.

- L White, (1987). Magomero: Portrait of an African Village, Cambridge University Press, pp. 79–81, 86–8, ISBN 0-521-32182-4.

- B. Pachai, (1978). Land and Politics in Malawi 1875–1975, p. 84.

- L White, (1987). Magomero: Portrait of an African Village, pp. 86–9.

- Nyasaland Protectorate, (1927). Report on the Census of 1926, Zomba, Superintendent of the Census.

- Nyasaland Protectorate, (1946). Report on the Census, 1945, Zomba, Superintendent of the Census.

- L White, (1987). Magomero: Portrait of an African Village, pp 83–6, 196–7.

- Nyasaland Protectorate (1929) Report of the Lands Officer on Land Alienations, Zomba, Government Printer.

- Nyasaland Protectorate (1935) Report of Committee Enquiring into Emigrant Labour, Zomba 1936, Government Printer.

- B Pachai, (1973). "Land Policies in Malawi: An Examination of the Colonial Legacy," The Journal of African History Vol. 14, pp. 687–8.

- Nyasaland Protectorate,(1928). "An Ordinance to Regulate the Position of Natives residing on Private Estates," Zomba, Government Printer

- A K Kandaŵire, (1979). Thangata: Forced Labour or Reciprocal Assistance?, Research and Publication Committee of the University of Malawi. pp.110–1.

- B Pachai, (1973). Land Policies in Malawi: An Examination of the Colonial Legacy, The Journal of African History Vol. 14, p 686.

- C Matthews and W E Lardner Jennings, (1947). The Laws of Nyasaland, Volume 1, London Crown Agents for the Colonies, pp 667–73.

- Nyasaland Protectorate, (1920) Report of a Commission to enquire into ... land, pp. 7–9, 14–15,

- J O Ibik, (1971). Volume 4: Malawi, Part II (The Law of Land, Succession etc). in A N Allott (editor), The Restatement of African Law, London, SOAS, pp. 6,11–12, 22–3.

- R M Mkandawire, (1992) The Land Question and Agrarian Change, in Mhone, G C (editor), Malawi at the Crossroads: The Post-colonial Political Economy, Harare, Sapes Books, pp. 174–5

- A Young, (2000). Land Resources: Now and for the Future, pp.415–16

- Nyasaland Protectorate, (1920) Report of a Commission to enquire into ... land, pp. 6–7.

- Nyasaland Protectorate, (1946). "Report of the Post-war Development Committee" Zomba, Government Printer, pp.91, 98.

- R Palmer, (1986). Working Conditions and Worker Responses on the Nyasaland Tea Estates, 1930–1953, p. 122.

- S Tenney and N K Humphreys, (2011). Historical Dictionary of the International Monetary Fund, pp. 10, 17–18.

- J McCraken, (2012). A History of Malawi 1859–1966, pp. 306–7.

- C Baker, (1993) Seeds of Trouble: Government Policy and Land Rights in Nyasaland, 1946–1964, London, British Academic Press pp. 54–5.

- C Baker, (1993). Seeds of Trouble, pp. 40, 42–4.

- B Pachai, (1973). Land and Politics in Malawi 1875–1975, pp. 136–7.

- British Geological Survey (1989) Review of lower Karoo coal basins and coal resources development with particular reference to northern Malawi. www.bgs.ac.uk/research/international/dfid-kar/WC89021_col.pd

- P. T. Terry (1961) African Agriculture in Nyasaland 1858 to 1894, The Nyasaland Journal, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 27–9.

- M Vaughan, (1987). The Story of an African Famine: Gender and Famine in Twentieth-Century Malawi, Cambridge University Press pp 60 1, 64–9.

- E. Mandala, (2006). Feeding and Fleecing the Native: How the Nyasaland Transport System Distorted a New Food Market, 1890s–1920s Journal of Southern African Studies, Vol. 32, No. 3, p. 521.

- P. T. Terry (1961) African Agriculture in Nyasaland 1858 to 1894, pp. 31–2

- J Bishop (1995). The Economics of Soil Degradation: An Illustration of the Change in Productivity Approach to Valuation in Mali and Malawi, London, International Institute for Environment and Development, pp. 59–61, 67.

- A Young, (2000). Land Resources: Now and for the Future, Cambridge University Press, p. 110. ISBN 0-521-78559-6

- S S Snapp, (1998). Soil Nutrient Status of Smallholder Farms in Malawi, Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis Vol. 29, pp 2572–88.

- John G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp.173, 176–8, 183.

- E. Mandala, (2006). Feeding and Fleecing the Native, pp. 512–4.

- F A Stinson, (1956). Tobacco Farming in Rhodesia and Nyasaland 1889–1956, Salisbury, the Tobacco Research Board of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, pp 1–2, 4, 73.

- C. A. Baker (1962) Nyasaland, The History of its Export Trade, The Nyasaland Journal, Vol. 15, No.1, pp. 15, 19.

- R Palmer, (1985). White Farmers in Malawi: Before and After the Depression, African Affairs Vol. 84 No.335 pp. 237, 242–243.

- J G Pike (1968) Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp 197–8.

- J McCracken, (1985). Share-Cropping in Malawi: The Visiting Tenant System in the Central Province c. 1920–1968, in Malawi: An Alternative Pattern of Development, University of Edinburgh, pp 37–8.

- Colonial Office, (1952), An Economic Survey of the Colonial Territories, 1951 Vol. 1, London, HMSO pp 44–5.

- P. T. Terry (1962). The Rise of the African Cotton Industry on Nyasaland, 1902 to 1918, The Nyasaland Journal, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 60–1, 65–6

- C. A. Baker (1962) Nyasaland, The History of its Export Trade, pp. 16, 20, 25.

- P. T. Terry (1962). The Rise of the African Cotton Industry on Nyasaland, p 67.

- C. A. Baker (1962) Nyasaland, The History of its Export Trade, pp. 18, 20, 24–6.

- R. B Boeder(1982) Peasants and Plantations in the Mulanje and Thyolo Districts of Southern Malawi, 1891–1951. University of the Witwatersrand, African Studies Seminar Paper pp. 5–6 http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/jspui/bitstream/10539/8427/1/ISS-29.pdf Archived 22 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp. 194–5, 198–9

- A Sen, (1981) Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlements and Deprivation, Oxford, The Clarendon Press. p. 165.

- L. White, (1987). Magomero: Portrait of an African Village, pp. 66–7.

- N Ball, (1976). Understanding the Causes of African Famine, Journal of Modern African Studies Vol.14 No.3, pp. 517–9.

- M. Vaughan, (1987). The Story of an African Famine: Gender and Famine in Twentieth-Century Malawi, Cambridge University Press pp. 65–6.

- E C Mandala, (2005). Feeding and Fleecing the Native, pp. 518–9.

- C Baker, (1994), Development Governor: A Biography of Sir Geoffrey Colby, London, British Academic Press pp 181, 194, 205.

- J Iliffe, (1984). The Poor in the Modern History of Malawi, in Malawi: An Alternative Pattern of Development, University of Edinburgh, p. 264.

- M. Vaughan, (1985). Famine Analysis and Family Relations: 1949 in Nyasaland, Past & Present, No. 108, pp. 180, 183, 190–2

- J Perry, (1969). The growth of the transport network of Malawi- The Society of Malawi Journal, 1969 Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 25–6, 29–30.

- E. Mandala, (2006). Feeding and Fleecing the Native, pp. 508–12.

- G. L. Gamlen, (1935). Transport on the River Shire, Nyasaland, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 86, No. 5, p. 451–2.

- Malawi Government Department of Antiquities, (1971) Lake Malawi Steamers (Zomba, Government Printer.

- A. MacGregor-Hutcheson (1969). New Developments in Malawi's Rail and Lake Services, The Society of Malawi Journal, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 32–4

- UK Colonial Office, (1929) Report on the Nyasaland Railway and Proposed Zambezi Bridge, London, HMSO, pp. 32, 37

- L. Gamlen, (1935). Transport on the River Shire, Nyasaland, pp.451–2.

- L. Vail, (1975). The Making of an Imperial Slum: Nyasaland and Its Railways, 1895–1935 The Journal of African History Vol. 16 pp. 96–101.

- Report on the Nyasaland Railway and Proposed Zambezi Bridge, pp. 11–14, 38–9.

- A. MacGregor-Hutcheson (1969). New Developments in Malawi's Rail and Lake Services, pp. 32–3.

- UK Colonial Office, An Economic Survey of the Colonial Territories, 1951 (London, HMSO, 1952), pp. 45–6.

- A. MacGregor-Hutcheson (1969). New Developments in Malawi's Rail and Lake Services, pp. 34–5.

- UK Colonial Office, (1938) Report of the Commission Appointed to Enquire into the Financial Position and Further Development of Nyasaland, London, HMSO, pp. 109–12, 292–5.

- J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 173–6.

- The Birth of an Airline: the Establishment of Rhodesian and Nyasaland Airways, Rhodesiana No. 21, http://www.rhodesia.nl/Aviation/rana.htm

- The Story of Central African Airways 1946–61, http://www.nrzam.org.uk/Aviation/CAAhistory/CAA.html

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 64–77, 80–3, 116–20.

- J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 129, 136, 142.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 101–2, 118–22.

- J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, p. 232–6.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 110–14.

- J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, p. 271, 313–16.

- A C Ross, (2009). Colonialism to cabinet crisis: a political history of Malawi African Books Collective, pp.65–6. ISBN 99908-87-75-6.

- J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp. 114–5, 135–7.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 246, 258, 269–70.

- A C Ross, (2009). Colonialism to Cabinet Crisis, p.62.

- J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, p. 129.

- J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 341–2.

- J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 344–5.

- J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp. 135–7.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 296–7.

- J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 349–51.

- C Baker, (1998). Retreat from Empire: Sir Robert Armitage in Africa and Cyprus, pp. 224–5.

- J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 356, 359.

- C Baker (2007). The Mechanics of Rebuttal, pp. 40–1.

- C Baker, (2007). The Mechanics of Rebuttal: The British and Nyasaland Governments' Response to The Devlin Report, 1959 The Society of Malawi Journal, Vol. 60, No. 2, p. 28.

- C Baker, (1997). State of Emergency: Nyasaland 1959, pp. 48–51, 61.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, p. 299.

- C Parkinson, (2007) Bills of Rights and Decolonization, The Emergence of Domestic Human Rights Instruments in Britain's Overseas Territories, Oxford University Press, p. 36. ISBN 978-0-19-923193-5.

- J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp. 150–1.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 287–94, 296–9, 309–13.

- J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp. 159, 170.

- De Robeck, A Pictorial Essay of the 1898 Provisional of British Central Africa – Nyasaland

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 595–598.

- Cana, Frank Richardson (1922). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 31 (12th ed.). pp. 1165–1166.

- The British Empire – Nyasaland

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)