Observational learning

Observational learning is learning that occurs through observing the behavior of others. It is a form of social learning which takes various forms, based on various processes. In humans, this form of learning seems to not need reinforcement to occur, but instead, requires a social model such as a parent, sibling, friend, or teacher with surroundings. Particularly in childhood, a model is someone of authority or higher status in an environment. In animals, observational learning is often based on classical conditioning, in which an instinctive behavior is elicited by observing the behavior of another (e.g. mobbing in birds), but other processes may be involved as well.[1]

Human observational learning

Many behaviors that a learner observes, remembers, and imitates are actions that models display and display modeling, even though the model may not intentionally try to instill a particular behavior. A child may learn to swear, smack, smoke, and deem other inappropriate behavior acceptable through poor modeling. Albert Bandura claims that children continually learn desirable and undesirable behavior through observational learning. Observational learning suggests that an individual's environment, cognition, and behavior all incorporate and ultimately determine how the individual functions and models.[2]

Through observational learning, individual behaviors can spread across a culture through a process called diffusion chain. This basically occurs when an individual first learns a behavior by observing another individual and that individual serves as a model through whom other individuals learn the behavior, and so on.[3]

Culture plays a role in whether observational learning is the dominant learning style in a person or community. Some cultures expect children to actively participate in their communities and are therefore exposed to different trades and roles on a daily basis.[4] This exposure allows children to observe and learn the different skills and practices that are valued in their communities.[5]

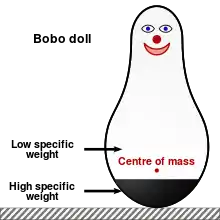

Albert Bandura, who is known for the classic Bobo doll experiment, identified this basic form of learning in 1961. The importance of observational learning lies in helping individuals, especially children, acquire new responses by observing others' behavior.

Albert Bandura states that people's behavior could be determined by their environment. Observational learning occurs through observing negative and positive behaviors. Bandura believes in reciprocal determinism in which the environment can influence people's behavior and vice versa. For instance, the Bobo doll experiment shows that the model, in a determined environment, affects children's behavior. In this experiment Bandura demonstrates that one group of children placed in an aggressive environment would act the same way, while the control group and the other group of children placed in a passive role model environment hardly shows any type of aggression.[6]

In communities where children's primary mode of learning is through observation, the children are rarely separated from adult activities. This incorporation into the adult world at an early age allows children to use observational learning skills in multiple spheres of life. This learning through observation requires keen attentive abilities. Culturally, they learn that their participation and contributions are valued in their communities. This teaches children that it is their duty, as members of the community, to observe others' contributions so they gradually become involved and participate further in the community.[7]

Influential stages and factors

The stages of observational learning include exposure to the model, acquiring the model's behaviour and accepting it as one's own.

Bandura's social cognitive learning theory states that there are four factors that influence observational learning:[8]

- Attention: Observers cannot learn unless they pay attention to what's happening around them. This process is influenced by characteristics of the model, such as how much one likes or identifies with the model, and by characteristics of the observer, such as the observer's expectations or level of emotional arousal.

- Retention/Memory: Observers must not only recognize the observed behavior but also remember it at some later time. This process depends on the observer's ability to code or structure the information in an easily remembered form or to mentally or physically rehearse the model's actions.

- Initiation/Motor: Observers must be physically and/intellectually capable of producing the act. In many cases, the observer possesses the necessary responses. But sometimes, reproducing the model's actions may involve skills the observer has not yet acquired. It is one thing to carefully watch a circus juggler, but it is quite another to go home and repeat those acts.

- Motivation: The observer must have motivation to recreate the observed behavior.

Bandura clearly distinguishes between learning and performance. Unless motivated, a person does not produce learned behavior. This motivation can come from external reinforcement, such as the experimenter's promise of reward in some of Bandura's studies, or the bribe of a parent. Or it can come from vicarious reinforcement, based on the observation that models are rewarded. High-status models can affect performance through motivation. For example, girls aged 11 to 14 performed better on a motor performance task when they thought it was demonstrated by a high-status cheerleader than by a low-status model.[9]

Some have even added a step between attention and retention involving encoding a behavior.

Observational learning leads to a change in an individual's behavior along three dimensions:

- An individual thinks about a situation in a different way and may have incentive to react to it.

- The change is a result of a person's direct experiences as opposed to being in-born.

- For the most part, the change an individual has made is permanent.[10]

Effect on behavior

According to Bandura's social cognitive learning theory, observational learning can affect behavior in many ways, with both positive and negative consequences. It can teach completely new behaviors, for one. It can also increase or decrease the frequency of behaviors that have previously been learned. Observational learning can even encourage behaviors that were previously forbidden (for example, the violent behavior towards the Bobo doll that children imitated in Albert Bandura's study). Observational learning can also influence behaviors that are similar to, but not identical to, the ones being modeled. For example, seeing a model excel at playing the piano may motivate an observer to play the saxophone.

Age difference

Albert Bandura stressed that developing children learn from different social models, meaning that no two children are exposed to exactly the same modeling influence. From infancy to adolescence, they are exposed to various social models. A 2013 study found that a toddlers' previous social familiarity with a model was not always necessary for learning and that they were also able to learn from observing a stranger demonstrating or modeling a new action to another stranger.[11]

It was once believed that babies could not imitate actions until the latter half of the first year. However, a number of studies now report that infants as young as seven days can imitate simple facial expressions. By the latter half of their first year, 9-month-old babies can imitate actions hours after they first see them. As they continue to develop, toddlers around age two can acquire important personal and social skills by imitating a social model.

Deferred imitation is an important developmental milestone in a two-year-old, in which children not only construct symbolic representations but can also remember information.[12] Unlike toddlers, children of elementary school age are less likely to rely on imagination to represent an experience. Instead, they can verbally describe the model's behavior.[13] Since this form of learning does not need reinforcement, it is more likely to occur regularly.

As age increases, age-related observational learning motor skills may decrease in athletes and golfers.[14] Younger and skilled golfers have higher observational learning compared to older golfers and less skilled golfers.

Observational causal learning

Humans use observational Moleen causal learning to watch other people's actions and use the information gained to find out how something works and how we can do it ourselves.

A study of 25-month-old infants found that they can learn causal relations from observing human interventions. They also learn by observing normal actions not created by intentional human action.[15]

Comparisons with imitation

Observational learning is presumed to have occurred when an organism copies an improbable action or action outcome that it has observed and the matching behavior cannot be explained by an alternative mechanism. Psychologists have been particularly interested in the form of observational learning known as imitation and in how to distinguish imitation from other processes. To successfully make this distinction, one must separate the degree to which behavioral similarity results from (a) predisposed behavior, (b) increased motivation resulting from the presence of another animal, (c) attention drawn to a place or object, (d) learning about the way the environment works, as distinguished from what we think of as (e) imitation (the copying of the demonstrated behavior).[16]

Observational learning differs from imitative learning in that it does not require a duplication of the behavior exhibited by the model. For example, the learner may observe an unwanted behavior and the subsequent consequences, and thus learn to refrain from that behavior. For example, Riopelle (1960) found that monkeys did better with observational learning if they saw the "tutor" monkey make a mistake before making the right choice.[17] Heyes (1993) distinguished imitation and non-imitative social learning in the following way: imitation occurs when animals learn about behavior from observing conspecifics, whereas non-imitative social learning occurs when animals learn about the environment from observing others.[18]

Not all imitation and learning through observing is the same, and they often differ in the degree to which they take on an active or passive form. John Dewey describes an important distinction between two different forms of imitation: imitation as an end in itself and imitation with a purpose.[19] Imitation as an end is more akin to mimicry, in which a person copies another's act to repeat that action again. This kind of imitation is often observed in animals. Imitation with a purpose utilizes the imitative act as a means to accomplish something more significant. Whereas the more passive form of imitation as an end has been documented in some European American communities, the other kind of more active, purposeful imitation has been documented in other communities around the world.

Observation may take on a more active form in children's learning in multiple Indigenous American communities. Ethnographic anthropological studies in Yucatec Mayan and Quechua Peruvian communities provide evidence that the home or community-centered economic systems of these cultures allow children to witness first-hand, activities that are meaningful to their own livelihoods and the overall well-being of the community.[20] These children have the opportunity to observe activities that are relevant within the context of that community, which gives them a reason to sharpen their attention to the practical knowledge they are exposed to. This does not mean that they have to observe the activities even though they are present. The children often make an active decision to stay in attendance while a community activity is taking place to observe and learn.[20] This decision underscores the significance of this learning style in many indigenous American communities. It goes far beyond learning mundane tasks through rote imitation; it is central to children's gradual transformation into informed members of their communities' unique practices. There was also a study, done with children, that concluded that Imitated behavior can be recalled and used in another situation or the same.[21]

Apprenticeship

Apprenticeship can involve both observational learning and modelling. Apprentices gain their skills in part through working with masters in their profession and through observing and evaluating the work of their fellow apprentices. Examples include renaissance inventor/painter Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, before succeeding in their profession they were apprentices.[22]

Learning without imitation

Michael Tomasello described various ways of observational learning without the process of imitation in animals[23] (ethology):

- Exposure – Individuals learn about their environment through close proximity to other individuals that have more experience. For example, a young dolphin learning the location of a plethora of fish by staying near its mother.

- Stimulus enhancement – Individuals become interested in an object from watching others interact with it.[24] Increased interest in an object may result in object manipulation, which facilitates new object-related behaviors by trial-and-error learning. For example, a young killer whale might become interested in playing with a sea lion pup after watching other whales toss the sea lion pup around. After playing with the pup, the killer whale may develop foraging behaviors appropriate to such prey. In this case, the killer whale did not learn to prey on sea lions by observing other whales do so, but rather the killer whale became intrigued after observing other whales play with the pup. After the killer whale became interested, then its interactions with the sea lion resulted in behaviors that provoked future foraging efforts.

- Goal emulation – Individuals are enticed by the end result of an observed behavior and attempt the same outcome but with a different method. For example, Haggerty (1909) devised an experiment in which a monkey climbed up the side of a cage, stuck its arm into a wooden chute, and pulled a rope in the chute to release food. Another monkey was provided an opportunity to obtain the food after watching a monkey go through this process on four separate occasions. The monkey performed a different method and finally succeeded after trial and error.[25]

Peer model influences

Observational learning is very beneficial when there are positive, reinforcing peer models involved. Although individuals go through four different stages for observational learning: attention; retention; production; and motivation, this does not simply mean that when an individual's attention is captured that it automatically sets the process in that exact order. One of the most important ongoing stages for observational learning, especially among children, is motivation and positive reinforcement.

Performance is enhanced when children are positively instructed on how they can improve a situation and where children actively participate alongside a more skilled person. Examples of this are scaffolding and guided participation. Scaffolding refers to an expert responding contingently to a novice so the novice gradually increases their understanding of a problem. Guided participation refers to an expert actively engaging in a situation with a novice so the novice participates with or observes the adult to understand how to resolve a problem.[26]

Cultural Variation

Cultural variation can be seen by the extent of information learned or absorbed by children in non-Western cultures through learning by observation. Cultural variation is not restricted only to ethnicity and nationality, but rather, extends to the specific practices within communities. In learning by observation, children use observation to learn without verbal requests for further information, or without direct instruction. For example, children from Mexican heritage families tend to learn and make better use of information observed during classroom demonstration than children of European heritage.[27][28] Children of European heritage experience the type of learning that separates them from their family and community activities. They instead participate in lessons and other exercises in special settings such as school.[29] Cultural backgrounds differ from each other in which children display certain characteristics in regards to learning an activity. Another example is seen in the immersion of children in some Indigenous communities of the Americas into the adult world and the effects it has on observational learning and the ability to complete multiple tasks simultaneously.[7] This might be due to children in these communities having the opportunity to see a task being completed by their elders or peers and then trying to emulate the task. In doing so they learn to value observation and the skill-building it affords them because of the value it holds within their community.[5] This type of observation is not passive, but reflects the child's intent to participate or learn within a community.[4]

Observational learning can be seen taking place in many domains of Indigenous communities. The classroom setting is one significant example, and it functions differently for Indigenous communities compared to what is commonly present in Western schooling. The emphasis of keen observation in favor of supporting participation in ongoing activities strives to aid children to learn the important tools and ways of their community.[27] Engaging in shared endeavors – with both the experienced and inexperienced – allows for the experienced to understand what the inexperienced need in order to grow in regards to the assessment of observational learning.[27] The involvement of the inexperienced, or the children in this matter, can either be furthered by the children's learning or advancing into the activity performed by the assessment of observational learning.[28] Indigenous communities rely on observational learning as a way for their children to be a part of ongoing activities in the community (Tharp, 2006).

Although learning in the Indigenous American communities is not always the central focus when participating in an activity,[28] studies have shown that attention in intentional observation differs from accidental observation. Intentional participation is “keen observation and listening in anticipation of, or in the process of engaging in endeavors”. This means that when they have the intention of participating in an event, their attention is more focused on the details, compared to when they are accidentally observing.

Observational learning can be an active process in many Indigenous American communities. The learner must take initiative to attend to activities going on around them. Children in these communities also take initiative to contribute their knowledge in ways that will benefit their community. For example, in many Indigenous American cultures, children perform household chores without being instructed to do so by adults. Instead, they observe a need for their contributions, understand their role in their community, and take initiative to accomplish the tasks they have observed others doing.[30] The learner's intrinsic motivations play an important role in the child's understanding and construction of meaning in these educational experiences. The independence and responsibility associated with observational learning in many Indigenous American communities are significant reasons why this method of learning involves more than just watching and imitating. A learner must be actively engaged with their demonstrations and experiences in order to fully comprehend and apply the knowledge they obtain.[31]

Indigenous communities of the Americas

Children from indigenous heritage communities of the Americas often learn through observation, a strategy that can carry over into adulthood. The heightened value towards observation allows children to multi-task and actively engage in simultaneous activities. The exposure to an uncensored adult lifestyle allows children to observe and learn the skills and practices that are valued in their communities.[5] Children observe elders, parents, and siblings complete tasks and learn to participate in them. They are seen as contributors and learn to observe multiple tasks being completed at once and can learn to complete a task while still engaging with other community members without being distracted.

Indigenous communities provide more opportunities to incorporate children in everyday life.[32] This can be seen in some Mayan communities where children are given full access to community events, which allows observational learning to occur more often.[32] Other children in Mazahua, Mexico are known to observe ongoing activities intensely .[32] In native northern Canadian and indigenous Mayan communities, children often learn as third-party observers from stories and conversations by others.[33] Most young Mayan children are carried on their mother's back, allowing them to observe their mother's work and see the world as their mother sees it.[34] Often, children in Indigenous American communities assume the majority of the responsibility for their learning. Additionally, children find their own approaches to learning.[35] Children are often allowed to learn without restrictions and with minimal guidance. They are encouraged to participate in the community even if they do not know how to do the work. They are self-motivated to learn and finish their chores.[36] These children act as a second set of eyes and ears for their parents, updating them about the community.[37]

Children aged 6 to 8 in an indigenous heritage community in Guadalajara, Mexico participated in hard work, such as cooking or running errands, thus benefiting the whole family, while those in the city of Guadalajara rarely did so. These children participated more in adult regulated activities and had little time to play, while those from the indigenous-heritage community had more time to play and initiate in their after-school activities and had a higher sense of belonging to their community.[38] Children from formerly indigenous communities are more likely to show these aspects than children from cosmopolitan communities are, even after leaving their childhood community[39]

Within certain indigenous communities, people do not typically seek out explanations beyond basic observation. This is because they are competent in learning through astute observation and often nonverbally encourage to do so. In a Guatemalan footloom factory, amateur adult weavers observed skilled weavers over the course of weeks without questioning or being given explanations; the amateur weaver moved at their own pace and began when they felt confident.[32] The framework of learning how to weave through observation can serve as a model that groups within a society use as a reference to guide their actions in particular domains of life.[40] Communities that participate in observational learning promote tolerance and mutual understand of those coming from different cultural backgrounds.[41]

Other human and animal behavior experiments

When an animal is given a task to complete, they are almost always more successful after observing another animal doing the same task before them. Experiments have been conducted on several different species with the same effect: animals can learn behaviors from peers. However, there is a need to distinguish the propagation of behavior and the stability of behavior. Research has shown that social learning can spread a behavior, but there are more factors regarding how a behavior carries across generations of an animal culture.[42]

Learning in fish

Experiments with ninespine sticklebacks showed that individuals will use social learning to locate food.[42]

Social learning in pigeons

A study in 1996 at the University of Kentucky used a foraging device to test social learning in pigeons. A pigeon could access the food reward by either pecking at a treadle or stepping on it. Significant correspondence was found between the methods of how the observers accessed their food and the methods the initial model used in accessing the food.[43]

Acquiring foraging niches

Studies have been conducted at the University of Oslo and University of Saskatchewan regarding the possibility of social learning in birds, delineating the difference between cultural and genetic acquisition.[44] Strong evidence already exists for mate choice, bird song, predator recognition, and foraging.

Researchers cross-fostered eggs between nests of blue tits and great tits and observed the resulting behavior through audio-visual recording. Tits raised in the foster family learned their foster family's foraging sites early. This shift—from the sites the tits would among their own kind and the sites they learned from the foster parents—lasted for life. What young birds learn from foster parents, they eventually transmitted to their own offspring. This suggests cultural transmissions of foraging behavior over generations in the wild.[45]

Social learning in crows

The University of Washington studied this phenomenon with crows, acknowledging the evolutionary tradeoff between acquiring costly information firsthand and learning that information socially with less cost to the individual but at the risk of inaccuracy. The experimenters exposed wild crows to a unique “dangerous face” mask as they trapped, banded, and released 7-15 birds at five different study places around Seattle, WA. An immediate scolding response to the mask after trapping by previously captured crows illustrates that the individual crow learned the danger of that mask. There was a scolding from crows that were captured that had not been captured initially. That response indicates conditioning from the mob of birds that assembled during the capture.

Horizontal social learning (learning from peers) is consistent with the lone crows that recognized the dangerous face without ever being captured. Children of captured crow parents were conditioned to scold the dangerous mask, which demonstrates vertical social learning (learning from parents). The crows that were captured directly had the most precise discrimination between dangerous and neutral masks than the crows that learned from the experience of their peers. The ability of crows to learn doubled the frequency of scolding, which spread at least 1.2 km from where the experiment started to over a 5-year period at one site.[46]

Propagation of animal culture

Researchers at the Département d’Etudes Cognitives, Institut Jean Nicod, Ecole Normale Supérieure acknowledged a difficulty with research in social learning. To count acquired behavior as cultural, two conditions need must be met: the behavior must spread in a social group, and that behavior must be stable across generations. Research has provided evidence that imitation may play a role in the propagation of a behavior, but these researchers believe the fidelity of this evidence is not sufficient to prove the stability of animal culture.

Other factors like ecological availability, reward-based factors, content-based factors, and source-based factors might explain the stability of animal culture in a wild rather than just imitation. As an example of ecological availability, chimps may learn how to fish for ants with a stick from their peers, but that behavior is also influenced by the particular type of ants as well as the condition. A behavior may be learned socially, but the fact that it was learned socially does not necessarily mean it will last. The fact that the behavior is rewarding has a role in cultural stability as well. The ability for socially-learned behaviors to stabilize across generations is also mitigated by the complexity of the behavior. Different individuals of a species, like crows, vary in their ability to use a complex tool. Finally, a behavior's stability in animal culture depends on the context in which they learn a behavior. If a behavior has already been adopted by a majority, then the behavior is more likely to carry across generations out of a need for conforming.

Animals are able to acquire behaviors from social learning, but whether or not that behavior carries across generations requires more investigation.[47]

Hummingbird experiment

Experiments with hummingbirds provided one example of apparent observational learning in a non-human organism. Hummingbirds were divided into two groups. Birds in one group were exposed to the feeding of a knowledgeable "tutor" bird; hummingbirds in the other group did not have this exposure. In subsequent tests the birds that had seen a tutor were more efficient feeders than the others.[48]

Bottlenose dolphin

Herman (2002) suggested that bottlenose dolphins produce goal-emulated behaviors rather than imitative ones. A dolphin that watches a model place a ball in a basket might place the ball in the basket when asked to mimic the behavior, but it may do so in a different manner seen.[49]

Rhesus monkey

Kinnaman (1902) reported that one rhesus monkey learned to pull a plug from a box with its teeth to obtain food after watching another monkey succeed at this task.[50]

Fredman (2012) also performed an experiment on observational behavior. In experiment 1, human-raised monkeys observed a familiar human model open a foraging box using a tool in one of two alternate ways: levering or poking. In experiment 2, mother-raised monkeys viewed similar techniques demonstrated by monkey models. A control group in each population saw no model. In both experiments, independent coders detected which technique experimental subjects had seen, thus confirming social learning. Further analyses examined copying at three levels of resolution.

The human-raised monkeys exhibited the greatest learning with the specific tool use technique they saw. Only monkeys who saw the levering model used the lever technique, by contrast with controls and those who witnessed poking. Mother-reared monkeys instead typically ignored the tool and exhibited fidelity at a lower level, tending only to re-create whichever result the model had achieved by either levering or poking.

Nevertheless, this level of social learning was associated with significantly greater levels of success in monkeys witnessing a model than in controls, an effect absent in the human-reared population. Results in both populations are consistent with a process of canalization of the repertoire in the direction of the approach witnessed, producing a narrower, socially shaped behavioral profile than among controls who saw no model.[51]

Light box experiment

Pinkham and Jaswal (2011) did an experiment to see if a child would learn how to turn on a light box by watching a parent. They found that children who saw a parent use their head to turn on the light box tended to do the task in that manner, while children who had not seen the parent used their hands instead.[52]

Swimming skill performance

When adequate practice and appropriate feedback follow demonstrations, increased skill performance and learning occurs. Lewis (1974) did a study[53] of children who had a fear of swimming and observed how modelling and going over swimming practices affected their overall performance. The experiment spanned nine days, and included many steps. The children were first assessed on their anxiety and swimming skills. Then they were placed into one of three conditional groups and exposed to these conditions over a few days.

At the end of each day, all children participated in a group lesson. The first group was a control group where the children watched a short cartoon video unrelated to swimming. The second group was a peer mastery group, which watched a short video of similar-aged children who had very good task performances and high confidence. Lastly, the third group was a peer coping group, whose subjects watched a video of similar-aged children who progressed from low task performances and low confidence statements to high task performances and high confidence statements.

The day following the exposures to each condition, the children were reassessed. Finally, the children were also assessed a few days later for a follow-up assessment. Upon reassessment, it was shown that the two model groups who watched videos of children similar in age had successful rates on the skills assessed because they perceived the models as informational and motivational.

Do-as-I-do Chimpanzee

Flexible methods must be used to assess whether an animal can imitate an action. This led to an approach that teaches animals to imitate by using a command such as “do-as-I-do" or “do this” followed by the action that they are supposed to imitate .[54] Researchers trained chimpanzees to imitate an action that was paired with the command. For example, this might include a researcher saying “do this” paired with clapping hands. This type of instruction has been utilized in a variety of other animals in order to teach imitation actions by utilizing a command or request.[54]

Observational learning in Everyday Life

Observational learning allows for new skills to be learned in a wide variety of areas. Demonstrations help the modification of skills and behaviors.[55]

Learning physical activities

When learning skills for physical activities can be anything that is learned that requires physical movement, this can include learning a sport, learning to eat with a fork, or learning to walk.[55] There are multiple important variables that aid in modifying physical skills and psychological responses from an observational learning standpoint. Modeling is a variable in observational learning where the skill level of the model is considered. When someone is supposed to demonstrate a physical skill such as throwing a baseball the model should be able to execute the behavior of throwing the ball flawlessly if the model of learning is a mastery model.[55] Another model to utilize in observational learning is a coping model, which would be a model demonstrating a physical skill that they have not yet mastered or achieved high performance in.[56] Both models are found to be effective and can be utilized depending on the what skills is trying to be demonstrated.[55] These models can be used as interventions to increase observational learning in practice, competition, and rehabilitation situations.[55]

Neuroscience

Recent research in neuroscience has implicated mirror neurons as a neurophysiological basis for observational learning.[57] These specialized visuomotor neurons fire action potentials when an individual performs a motor task and also fire when an individual passively observes another individual performing the same motor task.[58] In observational motor learning, the process begins with a visual presentation of another individual performing a motor task, this acts as a model. The learner then needs to transform the observed visual information into internal motor commands that will allow them to perform the motor task, this is known as visuomotor transformation.[59] Mirror neuron networks provide a mechanism for visuo-motor and motor-visual transformation and interaction. Similar networks of mirror neurons have also been implicated in social learning, motor cognition and social cognition.[60]

Clinical Perspective

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Discrete trial training (DTT) is a structured and systematic approach utilized in helping individuals with autism spectrum disorder learn.[61] Individuals with autism tend to struggle with learning through observation, therefore something that is reinforcing is necessary in order to motivate them to imitate or follow through with the task.[61] When utilizing DTT to teach individuals with autism modeling is utilized to aid in their learning. Modeling would include showing how to reach the correct answer, this could mean showing the steps to a math equation. Utilizing DTT in a group setting also promotes observational learning from peers as well.[61]

See also

References

- Shettleworth, S. J. "Cognition, Evolution, and Behavior", 2010 (2nd ed.) New York:Oxford,

- Bandura, A. (1971) "Psychological Modelling".New York: Lieber-Antherton

- Schacter, Daniel L.; Gilbert, Daniel Todd; Wegner, Daniel M. (2011). Psychology (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers. p. 295. ISBN 978-1-4292-3719-2. OCLC 755079969.

- Garton, A. F. (2007). Learning through collaboration: Is there a multicultural perspective?. AIP. pp. 195–216.

- Hughes, Claire (2011). Hughes, Claire. (2011) Social Understanding and Social Lives. New York, Ny: Psychology Press.

- "Most Human Behavior is learned Through Modeling".

- Fleer, M. (2003). "Early Childhood Education as an Evolving 'Community of Practice' or as Lived 'Social Reproduction': researching the 'taken-for-granted'" (PDF). Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. 4 (1): 64–79. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.486.6531. doi:10.2304/ciec.2003.4.1.7. S2CID 145804414.

- Bandura, Albert. "Observational Learning." Learning and Memory. Ed. John H. Byrne. 2nd ed. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. 482-484. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 6 Oct. 2014. Document URL http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CCX3407100173&v=2.1&u=cuny_hunter&it=r&p=GVRL&sw=w&asid=06f2484b425a0c9f9606dff1b2a86c18

- Weiss, Maureen R.; Ebbeck, Vicki; Rose, Debra J. (1992). ""Show and tell" in the gymnasium revisited: Developmental differences in modeling and verbal rehearsal effects on motor skill learning and performance". Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 63 (3): 292–301. doi:10.1080/02701367.1992.10608745. PMID 1513960.

- Weiss, Maureen et al. (1998). Observational Learning and the Fearful Child: Influence of Peer Models on Swimming Skill Performance and Psychological Responses. 380-394

- Shimpi, Priya M.; Akhtar, Nameera; Moore, Chris (2013). "Toddlers' Imitative Learning in Interactive and Observational Contexts: The Role of Age and Familiarity of the Model". Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 116 (2): 309–23. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2013.06.008. PMID 23896415.

- Meltzoff, A (1988). "Infants imitation after 1-week delay: Long -Term memory for novel acts and multiple stimuli". Developmental Psychology. 24 (4): 470–476. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.24.4.470. PMC 4137879. PMID 25147404.

- Bandura, A. (1989). Social Cognitive Theory. In R. Vasta (ED.), Annals of Child Development: Vol. 6. Theories of child development: Revised formulation and current issue (pp.1-60). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press

- Law, Barbi; Hall, Craig (2009). "The Relationships Among Skill Level, Age, and Golfers' Observational Learning Use". The Sport Psychologist. 23 (1): 42. doi:10.1123/tsp.23.1.42. S2CID 24462098.

- Meltzoff, A. N.; Waismeyer, A.; Gopnik, A. (2012). "Learning about causes from people: Observational causal learning in 24-month-old infants". Developmental Psychology. 48 (5): 1215–1228. doi:10.1037/a0027440. PMC 3649070. PMID 22369335.

- Zentall, Thomas R (2012). "Perspectives On Observational Learning In Animals". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 126 (2): 114–128. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.401.6916. doi:10.1037/a0025381. PMID 21895354.

- Riopelle, A.J. (1960). "Observational learning of a position habit by monkeys". Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 53 (5): 426–428. doi:10.1037/h0046480. PMID 13741799.

- Heyes, C. M. (1993). "Imitation, culture and cognition". Animal Behaviour. 46 (5): 999–1010. doi:10.1006/anbe.1993.1281. S2CID 53164177.

- Dewey, John (1916). Democracy and Education. New York: Macmillan Co.

- Gaskins, Paradise. The Anthropology of Learning in Childhood. Alta Mira Press. pp. Chapter 5.

- McLaughlin, L. J.; Brinley, J. F. (1973). "Age and observational learning of a multiple-classification task". Developmental Psychology. 9 (1): 9–15. doi:10.1037/h0035069.

- Groenendijk, Talita; Janssen, Tanja; Rijlaarsdam, Gert; Huub Van, Den Bergh (2013). "Learning to Be Creative. The Effects of Observational Learning on Students' Design Products and Processes". Learning and Instruction. 28: 35–47. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.05.001.

- Tomasello, M. (1999). The cultural origins of human cognition. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 248 pp.

- Spence, K. W. (1937). "Experimental studies of learning and higher mental processes in infra-human primates". Psychological Bulletin. 34 (10): 806–850. doi:10.1037/h0061498.

- Haggerty, M. E. (1909). "Imitation in monkeys". Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology. 19 (4): 337–455. doi:10.1002/cne.920190402.

- Schaffer, David et al. (2010). Developmental Psychology, Childhood and Adolescence. 284

- Cole, M. "Culture and early childhood learning" (PDF). Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- Mejia-Arauz, R.; Rogoff, B.; Paradise, R. (2005). "Cultural variation in children's observation during a demonstration". International Journal of Behavioral Development. 29 (4): 282–291. doi:10.1177/01650250544000062. S2CID 14778403.

- Rogoff, Barbara. "Cultural Variation in Children's Attention and Learning." N.p.: n.p., n.d. N. pag. PsycINFO. Web.

- Coppens, Andrew D.; Alcalá, Lucia; Mejía-Arauz, Rebeca; Rogoff, Barbara (2014). "Children's Initiative in Family Household Work in Mexico". Human Development. 57 (2–3): 116–130. doi:10.1159/000356768. ISSN 0018-716X. S2CID 144758889.

- Gaskins, Suzanne. "Open attention as a cultural tool for observational learning" (PDF). Kellogg Institute for International Studies University of Notre Dame. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- Rogoff, Barbara; Paradise, R.; Arauz, R.; Correa-Chavez, M. (2003). "Firsthand learning through intent participation". Annual Review of Psychology. 54: 175–203. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145118. hdl:10400.12/5953. PMID 12499516.

- Rogoff, Barbara; Paradise, Ruth; Correa-Chavez, M; Arauz, R (2003). "Firsthand Learning through Intent Participation". Annual Review of Psychology. 54: 175–203. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145118. hdl:10400.12/5953. PMID 12499516.

- Modiano, Nancy (1973). Indian education in the Chiapas Highlands. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. pp. 33–40. ISBN 978-0030842375.

- Paradise, Ruth; Rogoff, Rogoff (2009). "Side By Side: Learning By Observing and Pitching In" (PDF). Ethos. 37 (1): 102–138. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1352.2009.01033.x.

- Gaskins, Suzanne (Nov 1, 2000). "Children's Daily Activities in a Mayan Village: A Culturally Grounded Description". Cross-Cultural Research. 34 (4): 375–389. doi:10.1177/106939710003400405. S2CID 144751184.

- Rogoff, Barbara; Mosier, Christine; Misty, Jayanthi; Göncü, Artin (Jan 1, 1989). "Toddlers' Guided Participation in Cultural Activity". Cultural Dynamics. 2 (2): 209–237. doi:10.1177/092137408900200205. S2CID 143971081.

- Children's Initiative in Contributions to Family Work in Indigenous-Heritage and Cosmopolitan Communities in Mexico. (2014). 57(2-3).

- Rogoff, Barbara; Najafi, Behnosh; Mejía-Arauz, Rebeca (2014). "Constellations of Cultural Practices across Generations: Indigenous American Heritage and Learning by Observing and Pitching In". Human Development. 57 (2–3): 82–95. doi:10.1159/000356761. ISSN 0018-716X. S2CID 144340470.

- Gee, J.; Green, J (1998). "Discourse analysis, learning and social practice: A methodological study". Review of Research in Education.

- Often, children in Indigenous American communities find their own approach to learning and assume most of the responsibility for their learning.

- Frith, Chris D.; Frith, Uta (2012). "Mechanisms of Social Cognition". Annual Review of Psychology. 63: 287–313. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100449. PMID 21838544.

- Zentall, T. R.; Sutton, J. E.; Sherburne, L. M. (1996). "True imitative learning in pigeons". Psychological Science. 7 (6): 343–346. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00386.x. S2CID 59455975.

- Slagsvold, Tore (2011). "Social learning in birds and its role in shaping a foraging niche". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 366 (1567): 969–77. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0343. PMC 3049099. PMID 21357219.

- Slagsvold, T.; Wiebe, K. L. (2011). "Social learning in birds and its role in shaping a foraging niche". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 366 (1567): 969–977. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0343. PMC 3049099. PMID 21357219.

- Cornell, H. N., Marzluff, J. M., & Pecoraro, S. (2012). Social learning spreads knowledge about dangerous humans among American crows. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences,

- Claidiere, N.; Sperber, D. (2010). "Imitation explains the propagation, not the stability of animal culture". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 277 (1681): 651–659. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1615. PMC 2842690. PMID 19889707.

- Altshuler, D.; Nunn, A. (2001). "Obeservational learning in hummingbirds". The Auk. 118 (3): 795–799. doi:10.2307/4089948. JSTOR 4089948.

- Herman, L. M. (2002). Vocal, social, and self-imitation by bottlenosed dolphins. In K. Dautenhahn & C. Nehaniv (Eds.), Imitation in animals and artifacts (pp. 63–108). Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Kinnaman, A. J. (1902). "Mental life of two Macacus rhesus monkeys in captivity". The American Journal of Psychology. 13 (2): 173–218. doi:10.2307/1412738. JSTOR 1412738.

- Fredman, Tamar; Whiten, Andrew (2008). "Observational Learning from Tool using Models by Human-Reared and Mother-Reared Capuchin Monkeys (Cebus Apella)". Animal Cognition. 11 (2): 295–309. doi:10.1007/s10071-007-0117-0. PMID 17968602. S2CID 10437237.

- Pinkham, A.M.; Jaswal, V.K. (2011). "Watch and learn? Infants privilege efficiency over pedagogy during imitative learning". Infancy. 16 (5): 535–544. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7078.2010.00059.x. PMID 32693552.

- Weiss, Maureen et al. (1998). Observational Learning and the Fearful Child: Influence of Peer Models n Swimming Skill Performance and Psychological Responses. 380–394

- Gluck, Mark A. (2014). Learning and memory : from brain to behavior. Worth. ISBN 978-1-4292-9858-2. OCLC 842272491.

- McCullagh, Penny; Weiss, Maureen R. (2002), Van Raalte, Judy L.; Brewer, Britton W. (eds.), "Observational learning: The forgotten psychological method in sport psychology.", Exploring sport and exercise psychology (2nd ed.)., American Psychological Association, pp. 131–149, doi:10.1037/10465-007, ISBN 978-1-55798-886-7, retrieved 2020-05-05

- McCullagh, Penny; Ste-Marie, Diane; Law, Barbi (2014), "Modeling: Is what you see, what you get?", Exploring sport and exercise psychology (3rd ed.), American Psychological Association, pp. 139–162, doi:10.1037/14251-007, ISBN 978-1-4338-1357-3

- Lago-Rodríguez, A.; Cheeran, B.; Koch, G.; Hortobagy, T.; Fernandez-del-Olmo, M. (2014). "The role of mirror neurons in observational motor learning: an integrative review". European Journal of Human Movement. 32: 82–103.

- Rizzolatti, G.; Fogassi, L. (2014). "The mirror mechanism: recent findings and perspectives". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 369 (1644): 20130420. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0420. PMC 4006191. PMID 24778385.

- Jeannerod, M.; Arbib, M. A.; Rizzolatti, G.; Sakata, H. (1995). "Grasping objects: the cortical mechanisms of visuomotor transformation". Trends in Neurosciences. 18 (7): 314–320. doi:10.1016/0166-2236(95)93921-j. PMID 7571012. S2CID 6819540.

- Uddin, L. Q.; Iacoboni, M.; Lange, C.; Keenan, J. P. (2007). "The self and social cognition: the role of cortical midline structures and mirror neurons". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 11 (4): 153–157. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2007.01.001. PMID 17300981. S2CID 985721.

- Sigafoos, Jeff; Carnett, Amarie; O'Reilly, Mark F.; Lancioni, Giulio E. (2019), "Discrete trial training: A structured learning approach for children with ASD.", Behavioral interventions in schools: Evidence-based positive strategies (2nd ed.)., American Psychological Association, pp. 227–243, doi:10.1037/0000126-013, ISBN 978-1-4338-3014-3, S2CID 88498093

Further reading on animal social learning

- Galef, B.G.; Laland, K.N. (2005). "Social learning in animals: Empirical studies and theoretical models". BioScience. 55 (6): 489–499. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2005)055[0489:sliaes]2.0.co;2.

- Zentall, T.R. (2006). Imitation: Definitions, evidence, and mechanisms. Animal Cognition, 9 335–353. (A thorough review of different types of social learning) Full text