Occitano-Romance languages

The Occitano-Romance or Gallo-Narbonnese (Catalan: llengües occitanoromàniques; Occitan: lengas occitanoromanicas), or rarely East Iberian,[1] is a branch of the Romance language group that encompasses the Catalan/Valencian and Occitan languages spoken in parts of southern France and northeastern Spain.[2][3]

| Occitano-Romance | |

|---|---|

| Gallo-Narbonnese East Iberian | |

| Geographic distribution | France, Spain, Andorra, Monaco, Italy |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European |

Early forms | |

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | None |

Extent

The group covers the languages of the southern part of France (Occitania including Northern Catalonia), eastern Spain (Catalonia, Valencian Community, Balearic Islands, La Franja, Carche, Northern Aragon), together with Andorra, Monaco, parts of Italy (Occitan Valleys, Alghero, Guardia Piemontese), and historically in the County of Tripoli and the possessions of the Crown of Aragon. The existence of this group of languages is discussed on both linguistic and political bases.

Classification of Catalan

According to some linguists both Occitan and Catalan/Valencian should be considered Gallo-Romance languages. Other linguists concur as regarding Occitan but consider Catalan and Aragonese to be part of the Ibero-Romance languages.

The issue at debate is as political as it is linguistic because the division into Gallo-Romance and Ibero-Romance languages stems from the current nation states of France and Spain and so is based more on territorial criteria than historic and linguistic criteria. One of the main proponents of the unity of the languages of the Iberian Peninsula was Spanish philologist Ramón Menéndez Pidal, and for a long time, others such as Swiss linguist Wilhelm Meyer-Lübke (Das Katalanische, Heidelberg, 1925) have supported the kinship of Occitan and Catalan. Also, due to Aragonese not having been studied as much as both Catalan and Occitan, many people still label it as a Spanish dialect.[4]

From the 8th century to the 13th century, there was no clear sociolinguistic distinction between Occitania and Catalonia. For instance, the Provençal troubadour, Albertet de Sestaró, says: "Monks, tell me which according to your knowledge are better: the French or the Catalans? And here I shall put Gascony, Provence, Limousin, Auvergne and Viennois while there shall be the land of the two kings."[5] In Marseille, a typical Provençal song is called 'Catalan song'.[6]

Internal variation

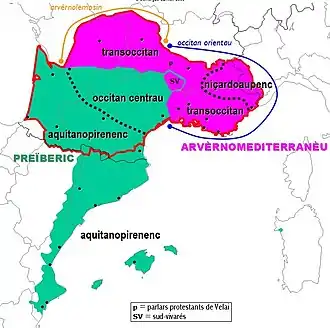

Most linguists separate Catalan and Occitan, but both languages have been treated as one in studies by Occitan linguists attempting to classify the dialects of Occitan in supradialectal groups, such is the case of Pierre Bec[7] and, more recently, of Domergue Sumien.[8]

Supradialectal classification of Occitano-Romance according to P. Bec

Supradialectal classification of Occitano-Romance according to P. Bec Supradialectal classification of Occitano-Romance according to D. Sumien

Supradialectal classification of Occitano-Romance according to D. Sumien

Both join together in an Aquitano-Pyrenean or Pre-Iberian group including Catalan, Gascon and a part of Languedocien, leaving the rest of Occitan in one (Sumien: Arverno-Mediterranean) or two groups (Bec: Arverno-Mediterranean, Central Occitan).

The answer to the question of whether Gascon or Catalan should be considered dialects of Occitan or separate languages has long been a matter of opinion or convention, rather than based on scientific ground. However, two recent studies support Gascon's being considered a distinct language. For the very first time, a quantifiable, statistics-based approach was applied by Stephan Koppelberg in attempt to solve this issue.[9] Based on the results he obtained, he concludes that Catalan, Occitan, and Gascon should all be considered three distinct languages. More recently, Y. Greub and J.P. Chambon (Sorbonne University, Paris) demonstrated that the formation of Proto-Gascon was already complete at the eve of the 7th century, whereas Proto-Occitan was not yet formed at that time.[10] These results induced linguists to do away with the conventional classification of Gascon, favoring the "distinct language" alternative. Both studies supported the early intuition of late Kurt Baldinger, a specialist of both medieval Occitan and medieval Gascon, who recommended that Occitan and Gascon be classified as separate languages.[11][12]

Linguistic variation

Similarities between Catalan, Occitan and Aragonese

- Both Catalan and Occitan have apocope on terminal latin vowels -Ĕ, -Ŭ (later -e, -o):

Latin Catalan Occitan Spanish Orthography IPA Orthography IPA Orthography IPA TRÚNCU(M) [ˈt̪rʊŋ.kʊ̃ˑ] tronc [tɾoŋ(k)] tronc [tɾuŋ(k)] tronco LIGNṒSU(M) [lʲɪŋˈn̪oː.sʊ̃ˑ] llenyós [ʎəˈɲos] lenhós [leˈɲus] leñoso This evolution does not occur when the ellision of -e or -o results in a terminal consonant cluster.

Latin Old Occitan Catalan Occitan ÁRBORE(M) ARBRE arbre arbre QUÁTTOR QUÁTRO quatre quatre - A large part of the lexicon is shared, and in general written words in Catalan and Occitan are mutually intelligible. Similar to the differences in lexicon between Portuguese and Spanish (although this is not always the case with spoken language and varies from dialect to dialect). There are also notable cognates between Catalan, Occitan and Aragonese.

English Latin Occitan Catalan Aragonese old VÉCLA(M) vielha vella viella middle / half MÉDIU(M) mièg mig meyo I ÉGO ieu ~ jo jo yo to follow SÉQUERE seguir ~ siegere seguir seguir(e) leaf FÓLIA(M) fuòlha ~ fuèlha fulla fuella ~ folla

Differences between Catalan and Occitan

Most of the differences of the vowel system stem from neutralizations that take place on unstressed syllables. In both languages a stressed syllable has a great number of possible different vowels, while phonologically different vowels end up being articulated in the same way in an unstressed syllable. Although this neutralization is common to both languages, the details differ markedly. In Occitan the form of neutralization depends on whether a vowel is pretonic (before the stressed syllable) or posttonic (after the stressed syllable). For example /ɔ/ articulates as [u] in pretonic position and as [o] in posttonic position, and only as [ɔ] in stressed position. In contrast neutralization in Catalan is the same regardless of the position of the unstressed syllable (although it differs from dialect to dialect). Many of these changes happened in the 14th or late 13th century.

Slightly older are the palatalizations present in Occitan before a palatal or velar consonant:

| Occitan | Catalan | English |

|---|---|---|

| vielha | vella | Old |

| mièg | mig | Middle/Half |

| ieu/jo | jo | I |

| seguir | seguir | To follow |

| fuèlha | fulla | Leaf |

Lexical comparison

Variations in the spellings and pronunciations of numbers in several Occitano-Romance dialects:[13][14]

| Numeral | Occitan | Catalan | Aragonese[15] | PROTO- OcRm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Occitan | Western Occitan | Eastern Occitan | Eastern Catalan | Northwestern Catalan | |||||

| Auvergnat | Limousin | Gascon | Languedocien | Provençal | |||||

| 1 | vyn / vynɐ vun / vunå | ỹ / ynɔ un / una |

y / yo un / ua |

ỹ / yno un / una | yŋ / yno un / una |

un / unə un / una |

un / una un / una |

un~uno / una un~uno / una | *un / *una |

| 2 | du / dua dou / duas | du / dua dos / doas |

dys / dyos dus / duas |

dus / duos dos / doas | dus / duas dous / douas |

dos / duəs dos / dues |

dos/dues dos / dues |

dos / duas dos / duas | *dos~dus / *duas |

| 3 | tʀei trei | trei tres |

tres tres |

tres tres | tʀes tres |

trɛs tres |

trɛs tres | tɾes tres | *tres |

| 4 | katʀə catre | katre quatre |

kwatə quatre |

katre quatre | katʀə quatre |

kwatrə quatre |

kwatre quatre |

kwatro~kwatre quatro / quatre | *kwatre |

| 5 | ʃin sin | ʃin cinc |

siŋk cinq |

siŋk cinq | siŋ cinq |

siŋ / siŋk cinc |

siŋ / siŋk cinc | θiŋko~θiŋk cinco / cinc | *siŋk |

| 6 | ʃei siei | ʃiei sieis |

ʃeis sheis |

siɛis sièis | siei sieis |

sis sis |

sis sis |

seis~sieis seis / sieis | *sieis |

| 7 | se sé | ʃe sèt |

sɛt sèt |

sɛt sèt | sɛ sèt |

sɛt set |

sɛt set | siet~sɛt siet / set | *sɛt |

| 8 | vø veu | jɥe uèch |

weit ueit |

ɥet͡ʃ uèch | vɥe vue |

buit / vuit vuit |

vuit / wit vuit / huit |

weito~weit ueito / ueit | *weit |

| 9 | niø~nou nieu~nou | nɔu nòu |

nau nau |

nɔu nòu | nu nòu |

nɔu nou |

nɔu nou | nweu~nɔu nueu / nou | *nɔu |

| 10 | die~de dié~dé | diɛ~de detz |

dɛt͡s dètz |

dɛt͡s dèts | dɛs dès |

dɛu deu |

dɛu deu | dieθ~deu diez / deu | *dɛt͡s |

The numbers 1 and 2 have both feminine and masculine forms agreeing with the object they modify.

References

- "Ibero-Romance". Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "Mas se confrontam los parlars naturals de Catalonha e d'Occitania, i a pas cap de dobte, em en preséncia de parlars d'una meteissa familha linguistica, la qu'ai qualificada d'occitano-romana, plaçada a egala distància entre lo francés e l'espanhòl." Loís Alibèrt, Òc, n°7 (01/1950), p. 26

- Lozano Sierra J, Saludas Bernad A.. Aspectos morfosintácticos del Belsetán. Saragossa: Gara d'Edizions, 2007, p. 180. ISBN 84-8094-056-5.

- Tomás Arias, Javier. Elementos de lingüística contrastiva en aragonés: estudio de algunas afinidades con gascón, catalán y otros romances (Thesis). Universitat de Barcelona, 2016-07-08

- Monges, causetz, segons vostre siensa qual valon mais, catalan ho francés?/ E met de sai Guascuenha e Proensa/ E lemozí, alvernh’ e vianés/ E de lai met la terra dels dos reis.

- Manuel Milá y Fontanals (1861). De los trovadores en España: Estudio de lengua y poesía provenzal. J. Verdaguer. p. 14.

- Pierre BEC (1973), Manuel pratique d’occitan moderne, coll. Connaissance des langues, Paris: Picard

- Domergue SUMIEN (2006), La standardisation pluricentrique de l'occitan: nouvel enjeu sociolinguistique, développement du lexique et de la morphologie, coll. Publications de l'Association Internationale d'Études Occitanes, Turnhout: Brepols

- Stephan Koppelberg, El lèxic hereditari caracteristic de l'occità i del gascó i la seva relació amb el del català (conclusions d'un analisi estadística), Actes del vuitè Col·loqui Internacional de Llengua i Literatura Catalana, Volume 1 (1988). Antoni M. Badia Margarit & Michel Camprubi ed. (in Catalan)

- Chambon, Jean-Pierre; Greub, Yan (2002). "Note sur l'âge du (proto)gascon". Revue de Linguistique Romane (in French). 66: 473–495.

- Baldinger, Kurt (1962). "La langue des documents en ancien gascon". Revue de Linguistique Romane (in French). 26: 331–347.

- Baldinger, Kurt (1962). "Textes anciens gascons". Revue de Linguistique Romane (in French). 26: 348–362.

- "Indo-European numerals (Eugene Chan)". Archived from the original on 2012-02-12. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- Cardinals en l'argonés

- "Los números en aragonés: Cardinales". Archived from the original on 2019-04-21. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)