Ocean colonization

Ocean colonization is the theory of extending society territorially to the ocean by permanent settlements floating on the ocean surface and submerged below, employing offshore construction.[1] In a broader sense the ocean being subject of colonization and colonialism has been critically identified with exploitive ocean development, such as deep sea mining.[2][3] In this regard blue justice groups have also used the term blue colonization.[4]

The process of extending space available for humans to inhabit involves developing seasteads such as artificial islands, floating rigid structures, extreme-sized cruise ships or even submerged structures, to provide permanent living quarters for sections of the world's population.[1] Specifically catering for the growing issue of overpopulation, and need for extra housing as a result, the urban theorists that have pursued this idea also suggesting it as a sustainable form of living to help assist climate change [5] Colonies may form their own sovereign state of independence,[6] with these structures also being generally less impacted by natural disasters.[7]

However this theory for future urban planning has been critiqued by other scientists, suggesting that developing artificial structures in an aquatic environment will disrupt the natural marine ecosystem[8] and may instead be impacted by aquatic natural disasters such as tsunamis. The debate against this theory further notes the threat of security of these colonies and the potential lack of protection without an overseeing government or body.[6]

The utopian theory of ocean colonisation has been explored and visually explained in many forms of entertainment such as in gaming, virtual realities and science-fiction movies, to show the potentially positive and negative changes on societies daily living.

Lessons learned from ocean colonization may prove applicable to space colonization. The ocean may prove simpler to colonize than space and thus occur first, providing a proving ground for the latter. In particular, the issue of sovereignty may bear many similarities between ocean and space colonization; adjustments to social life under harsher circumstances would apply similarly to the ocean and to space; and many technologies may have uses in both environments [9]

Technologies

Underwater construction

Underwater habitats are examples of underwater structures.

Submerged Structures

Submerged structures are sunken, air-tight vessels that either sit at an intermediate position or attached to the ocean floor that create an underwater metropolis for residences and businesses.[10]

Proposed Designs

H2ome is a project for building sea floor homes, along with high-end resorts and hotels.[11]

Ocean Spiral City is a $26 billion Japanese project,[9] with research and designing being underway to potentially house 5000 people and may be a reality by 2030.[12]

Offshore construction

Offshore construction is one of the main forms of ocean colonization.

Land reclamation

Land reclamation, or artificial islands, are the man-made process of relocating rock or placing cement in a sea, ocean or river bed, to extend or create a new area of liveable land in the ocean.[13] This process involves creating a solid base on the sea floor and further building upon it with materials such as clay, sand and soil to form a new island-like structure above the water surface.[8] It therefore expands the area for potential development space, supporting the erection of buildings or other necessary urban developments in response to support human activities, by utilising this otherwise untouched space for more ‘productive’ uses.[8] This ocean colonisation technique is the most developed in terms of planning and implementation in the present day.

Palm Jumeriah

The Palm Jumeriah is the main of the three artificial islands in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, to be developed. The name ‘Palm’ resembles its palm-tree like design when viewed aerially, and is both culturally and symbolically relevant to the coastal city.[8] This land reclamation project began in 2001 and involved the movement of 94 million cubic metres of sand and 5.5 million cubic metres of rock off-shore in the Persian Gulf, to allow the development of luxury beachfront villas for both residential and commercial purposes.[8]

Kansai International Airport

Kansai International Airport located in Osaka Bay, Japan was created in 1987, due to overcrowding at the nearby Osaka Airport.[14] Developers suggested Japan's mountain terrain [14] is not conducive to the development of necessary flat space required for an airport and thus developed an artificial island in the bay, with a connecting bridge to support both travel and freight arrivals and departures.

Portier Cove

Portier Cove is a new eco-district extended off the coast of Monaco designed to reduce greenhouse emissions in the area.[15] The 125m long extension project re-began in 2011 and plans to provide a hectare of space for retail, parks, offices, apartments and private villas, to support their national issue of a growing population.[15]

Floating structures

Very Large Floating Structures (VLFS) [16] or Seasteads[7] are artificially man-made pontoons, designed to float on the surface of the ocean or sea to house permanent residents. They have a large surface area and are designed to not be bound to a certain government but instead form their own community through clusters of floating structures.[6] This type of technology has only be theorised and is yet to be developed, however a variety of companies have investment project plans underway.

The Seasteading Institute

Seasteading refers to building buoyant, permanent structures to float on the surface of the ocean to support human settlements and colonies.[5]

The idea constructed by Friedman and Gramlich, who founded the Seasteading Institute, is now defined in the Oxford English Dictionary. The pair received $500k funding from PayPal founder Peter Thiel, to begin designing and constructing their idea in 2008 [17]

Oceanix City

Architectural company BIG proposed their design of the Oceanix City, involving a series of inhabitable floating villages, clustered together to form an archipelago that could house 10,000 residents.[18] The proposed design was developed in response to the effects of climate change such as rising sea levels and an increase in hurricanes in the Polynesian region, that threaten many tropical island nations from being eradicated. The design also outlines its intentions to incorporate predominantly renewable energy sources such as wind and water.[18]

Cruise Ships

The idea of cruise ships as part of the theory of ocean colonisation, surpass the typical modern-day commercial cruise ships. This technology imagines a large scale vessel, supporting permanent residence on board that can freely move about the world's oceans and seas.[1] These ships include residential, retail, sport, commercial and entertainment quarters on board.[19]

Freedom Ship

The ideal size and style is outlined in the concept of the proposed Freedom Ship design by US engineer Norman Nixon, proposing a 4000 ft length vessel that has the capability to house 60,000 residents and 15,000 personnel [20] - with an estimated cost of $10 billion (USD).[17]

MS The World

MS The World debuted in 2015, sitting at 644 feet (196 m) long and is the largest, residential cruise ship presently in the world.[19] This vessel is the closest, existent ship to the idealised ‘Freedom Ship’ design that hopes to support permanent life on board a ship. Permanent residency on the ship costs between $3million (USD) to $15million (USD) per room.[19]

Impacts of theory

Climate change

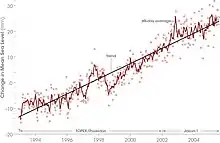

It is predicted by 2100, sea levels will have risen by 1–3 meters as a result of global warming, to which by 2050 are estimated to impact 90% of the world's coastal cities.[18] Theorists who support ocean colonization theories hope to face the issue and provide a solution for groups and nations worldwide that are most at risk.[18]

For example, Polynesian island nations such as Tuvalu with a population of 10,000 are expected to be fully submerged by water in approximately 30–50 years [21]

Entrepreneurs who have devised these technologies to support the colonization of the seas suggest their design will have an overall minimal carbon footprint.[5]

Recycled and environmentally-friendly materials such as recycled plastics and locally sourced coconut fibres will constitute a large proportion of building materials required for construction.[22][5]

To minimise the use of pollutant energy output in the environment contributing to this rapid global warming, designers suggest using predominantly renewable energy from sources such as water, wind [17] and solar power.[22] Designers also intend to utilize bicycles, electric and hydrogen vehicles as the primary transport system on board to prevent extra CO2 emissions.[22] Ultimately, project designers, entrepreneurs and scientists are aiming to collaborate to create a structure allowing “the formation of an eco-sustainable production and consumption cycle in the future human habitat”.[22]

The primary group impacted by the effects of climate change, the Pacific Island Nations, are the target demographic identified for the ocean colony projects to which they are still able to remain in their familiar and culturally significant island environment. In 2017, French Polynesia signed an agreement with the Seasteading Institute to utilise their land for testing of the world's first floating town.[23]

Green Float is another example of a project hoping to develop a carbon negative city within the Equatorial Pacific Ocean, with it set to house 100,000 locals by joining multiple floating modules.[24] They hypothesise a 40% reduction in CO2 emissions through more environmentally friendly and energy efficient modes of transport and power [24]

Protection from natural disasters

The number of natural disasters occurring in the world has grown by 357 from 1919 to 2019, according to Our World in Data,[25] with 90,000 people killed annually as a result of this extreme weather.[9] According to this data, the main economic impacts have primarily come from extreme weather events, wildfires and flooding.[9] Due to these economic effects, cities such as Boston, Miami and San Francisco are exploring this idea of ocean colonization as they try to protect their coastlines from an increase in flooding, rising sea levels and earthquakes respectively.[18] Ocean colony technologies are said to be less impacted by common territorial natural disasters and even extreme aquatic weather such as damaging waves as they occupy more shallow waters.[23] For example, the world's first floating hotel, the Barrier Reef Floating Resort,[26] sat 70 km off the coast of Townsville, Australia and in 1988 withheld against a cyclone.[23]

Aquatic natural disasters

According to theorists and scientists at the Seasteading Institute who have begun conducting research into aquatic environments as liveable spaces, many of the technologies supporting ocean colonization are set to mainly be impacted by rogue waves [7] and storms. However, other aquatic natural disasters such as Tsunamis, Friedman says would have little impact on the structures yet only raise water levels.[7]

Research in the 1990s emerged regarding the hydro-elasticity of rigid structures at the face of relentless and on-going wave movement [16] to which lead to modern scientists such as Suzuki (2006), voicing their concern of the potentially poor integrity of aquatic structures impacting by constant motion and vibration.[16] Further modern research and design has also been situated around testing the computation fluid dynamics of resistance against vortex formations of water,[16] such as cyclones that form and therefore threaten ocean environments.

Spar platforms, artificial and natural breakwaters and active repositioning, if applicable, of ocean structures to avoid storms are some suggestions and technologies suggested by ocean colonization supporters and scientists to combat extreme aquatic weather events.[7] Entrepreneurs such as Friedman, have acknowledged and are aware of the care that must be taken in the engineering process of these designs.[7]

Disruption to marine ecosystem

Biologists have identified the individualised negative impacts of the technologies that support the implementation of colonization, by their effect on the disruption to the local marine ecosystem.

According to scientists, the process of land reclamation can lead to the erosion of natural soil and land,[8] through this human-made and unnatural movement of sediment that consequently disrupts the natural geological cycle.

Scientists at Marine Insight, have conducted studies of the environmental impacts of commercial cruise ships,[27] with these impacts predicted to be similar to the technologies allowing ocean colonization. Currently, these vessels cause air pollution through the emission of toxic gases that increase in the acidification of the ocean.[27]

Their research also showed the noise pollution from these ships can disturb the hearing of marine animals and mammals.[27]

Furthermore, the leaking of chemicals, grey water and blackwater into the ocean can lead to the accumulation of harmful chemicals, increasing the water concentration,[27] that local flora and fauna are accustomed to. These studies of cruise ships and their impact of the marine environment have been incorporated by ocean colonization scientists and designers, as they are the closest, existent technology to their proposed projects.

Overpopulation/housing shortage crisis

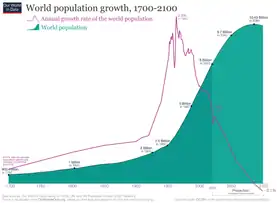

Ocean colonization is said by theorists to be a potential solution to the world's growing population, with 7.78 billion people currently inhabiting Earth as of May 2020.[28] The BBC claim that 11 billion people is Earth's carrying capacity even after adjusting consumption behaviours,[9] with the UN predicting this number to be reached by 2100.[9] With the world's oceans covering 70% of the planet's surface,[29] this space has been therefore seen as a viable, long-term solution to allow an expansion and extension of inhabitable space by 50%.[9] Pioneers of this colonization theory suggest the new spaces to also cater for new and more jobs, and may be a particular solution to the moral and political dilemma of housing as well as the consequential increased number of climate refugees.[30]

Sovereign independence

Central entrepreneurs to this theory have suggested that it hosts the potential for a degree of autonomy of residences, currently operating in more strict political systems.[6] As a result, ocean colonisation has been posed as a potential solution to poor governance,[31] in which sovereign states may begin formation of greater personal freedoms, little state regulation and clearly defined state intentions.[6] Despite critical theorists at the Seasteading Institute suggesting their design to allow people to “experiment with new forms of government”,[23] however socialists critique this idea, seeing it as a possibility bypass tax laws [16] in international waters. Projects such as the Freedom Ship and those by the Seasteading Institute,[16] have proposed the idea for the installation of their designs in Polynesian water however are exempt by unique governing framework permitting significant autonomy from Polynesian laws.[6]

Under Article 60 of the United Nations Convention on Law of the Seas (UNCLOS), “artificial islands, installations and structures” have the right to build in exclusive economic zones to coastal nations, however these coastal nations still hold sovereignty of the 12 nautical miles adjacent to that coast.[31]

Little has been vocalised on the development of essential services i.e. schools, hospitals etc., within these ocean colony structures yet theorists say it is likely host or closest nations will be relied upon until the initial population grows.[6] With intentions to build beyond territorial seas in exclusive economic zones,[31] the likelihood of the idea for pure sovereignty has been questioned by critics.

Expense

According entrepreneurs at the Seasteading Institute, their particular technology of floating modules is said to be high, with a predicted cost of $10,000 - $100,000 per 1 acre of a seastead, comprised purely by volunteers.[7] Similarly, Friedman, co-founder of the Seasteading Institute, has estimated the entire project to cost a few hundred million.[17] As mentioned earlier, other projects such as the Ocean Spiral City, are set to cost $26 billion [9]

Critics have responded to these future plans; labelling them as “elitist, impractical and delusional”,[23] with “the number of people accommodated limited”.[6]

These projects will therefore rely on investors, which is acknowledged by ocean colonization theorists who state the “first people to benefit will be the privileged who can afford to invest in the project”.[7] However skeptics criticize the idea suggesting it is ultimately designed for capitalist gain, rather than a potential solution for the future society.[6]

Lack of security

Without an overseeing government and lack of taxes, critics of ocean colonisation suggest there would be little security provided in the open waters,[17] in terms of economically and regarding human rights laws. Theorists are considered by threat of being prey to pirates,[23] with colonies on board therefore having minimal personal protection.

There has been resistance to this seemingly capital-intensive project, as critics of the idea suggest private law cannot be embraced if it challenges that of the public laws.[6] Ocean colonization theorists have acknowledged the necessary assignment of responsibility of land and resources into private hands,[6] to ensure that a party is liable. This assigned responsibility is suggested to rely upon existing legal frameworks regarding property, contract and commercial laws to protect colonies.[6] Ocean colonisation theorists are currently working to balance the idea of freedom with security [7]

Adaptations to living

Developing these technologies and strategies will ultimately require changes to daily living.

Positive

Many current day activities will remain relatively unchanged and un-impacted, such as many of the ‘modern necessities’ i.e. heating, lighting, kitchen appliances, hot water systems.[7] ‘They would require specially consideration and design, however most technologies would still be available’ says Friedman.[7]

With such proximity to water resources, there would be a reliance on hydroponics to account for the limited space on the surface,[7] that would generate energy and support the growth of crops.[22] Similarly, to conserve space, vertical gardens have been suggested by designers for growing and composting.[7]

Humans are more likely to accustom to this environment, as psychologically they are more comfortable with water,[9] with humanity gradually moving to reside to coast and have historically always operated close to water ways.[23]

Negative

On the other hand, humans are less likely to adapt to this possible solution as the ocean is an unfamiliar territory and they are familiar with their ways on land.[7] Life on the water would also be incredibly different, with limited personal living space and many more shared spaced instead.[7] There is also the threat of possible overfishing of nearby and local species to the colony,[22] and also the raised question of waste disposal.[22] With limited ability of fresh water availability, due to the inability to drill or stream it,[7] critics and theorists of the idea themselves suggest and acknowledge that ocean colonies are unable to ever be purely self-sufficient.[7]

Progress

Land reclamation, followed by Seasteading, are the two technologies leading the way in terms of development plans.

In 2017, the Seasteading Institute proposed to begin building the first project village by 2020 in a lagoon in Tahiti.[5] Investor in the project, John Quirk, stated in 2018, that “we could conceivably see our first modest seastead for 300 people by 2022”.[23]

In terms of law, in 2019, plans were passed allowing a nation to host the first seastead, to which it must adhere to the regulations of that host country but is also liable for its own tailored ‘Special Economic Zone’.[32] Economic freedom is likely to be sought after and granted, but more gradually through a staged approach called ‘strategic incrementalism’.[32]

As of May 2020, both the Seastead Institute and Blue Frontiers have completed their impact assessments and are waiting for updates on their proposal.[23]

See also

References

- Bolonkin, Alexander (2008). Floating Cities, Islands and States. University of New York. pp. 1–6, 11.

- Watts, Jonathan (2021-09-27). "Race to the bottom: the disastrous, blindfolded rush to mine the deep sea". the Guardian. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- Ranganathan, Surabhi (2020-12-10). "Decolonization and International Law: Putting the Ocean on the Map". Journal of the History of International Law / Revue d'histoire du droit international. Brill. 23 (1): 161–183. doi:10.1163/15718050-12340168. ISSN 1388-199X. S2CID 234549799.

- "A Pacific resistance to Blue colonization". Karibu Foundation. 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- Tangerman, V. (11 December 2007). "Life at sea? 6 futuristic homes that will protect you from climate change". Futurism.

- Ranganathan, S (2019). "Seasteads, land-grabs and international law" (PDF). International Legal Theory: Symposium on Land-Grabbing. 1: 205–214.

- Friedman, Gramlich (2009). Seasteading: a practical guide to homesteading the high seas. Palo Alto: Seasteading Institute.

- Gibling, C. "Construction Process and Post-Construction Impacts of the Palm Jumeirah in Dubai, United Arab Emirates" (PDF). Coastal and Ocean Engineering. 1: 1–4.

- Ananeva, Ella (23 May 2019). "7 Reasons Why We Should Colonize Oceans Instead Of Mars". Medium.

- "Japan's Ocean Spiral proposed as giant underwater city". CNN Business. 3 November 2015.

- Pandey, Wedita (2015). "These Companies Are Making Underwater Homes Happen Around The World". Proptiger. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- Alexander, Donovan (28 December 2018). "7 Things You Should Know About the Future of Underwater Cities". Interesting Engineering.

- Stauber, J (2016). Marine Ecotoxicology. Massachusetts: Massachusetts: Academic Press. pp. 273–313.

- Funk, Mesri (2015). "Settlement of the Kansai International Airport Islands". Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering.

- Baldwin, E (22 April 2019). "Renzo Piano Designs "Floating" Seaside Residences for Monaco's New Eco-District". Arch Daily.

- Wang, Tay (2011). "Very Large Floating Structures: Applications, Research and Development". Procedia Engineering: 14, 62–72.

- Madrigal, Alexis (18 May 2008). "Peter Thiel Makes Down Payment on Libertarian Ocean Colonies". Wired.

- Gibson, E (2019). "BIG unveils floating Oceanix City that can withstand hurricanes". Dezeen.

- Marsh, J (2020). "The World: a floating city of millionaires". CNN Travel.

- Anish (2019). "The Freedom Ship Floating City Concept". Marine Insight.

- "Tuvalu about to disappear into the ocean". Reuters. 13 September 2007.

- Kizilova, Svetlana (2019). "Aqua-architecture as an autonomous system: metabolic components of the complete ecological cycle" (PDF). Fundamentals of Architectural Design. 135: 03019. Bibcode:2019E3SWC.13503019K. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/201913503019.

- Smith, Carl (18 June 2018). "Is 'seasteading' a delusion or could floating cities be a lifeline for Pacific nations?". ABC News.

- Quick, Darren (10 November 2010). "Green Float concept: a carbon negative city on the ocean". News Atlas.

- "Number of recorded natural disaster events, All natural disasters, 1900 to 2019". Our World in Data. 2020.

- Shelton, Tracey (24 October 2019). "Australia's world-first floating hotel in dire straits as Kim Jong-un seeks renovations". ABC News.

- "8 Ways Cruise Ships Can Cause Marine Pollution". Marine Insight. 7 October 2019.

- "Current World Population". Worldometer. 2020.

- "How much water is in the ocean?". National Ocean Website. 20 March 2020.

- Kaye, Leon (1 February 2017). "Could Floating Cities Help Us Adapt to Climate Change?". Triple Pundit.

- Singh, Prabhakar (21 May 2019). "Are floating cities legal?". The Telegraph India.

- Jackson, Carly (22 October 2019). "Seasteading! What about Regulations?". The Seasteading Institute.