Ochroconis gallopava

Ochroconis gallopava, also called Dactylaria gallopava or Dactylaria constricta var. gallopava, is a member of genus Dactylaria. Ochroconis gallopava is a thermotolerant, darkly pigmented fungus that causes various infections in fowls, turkeys, poults, and immunocompromised humans[1][2][3][4] first reported in 1986.[2] Since then, the fungus has been increasingly reported as an agent of human disease[2] especially in recipients of solid organ transplants (e.g., liver, kidney, heart, and lung).[1][2][3][4] Ochroconis gallopava infection has a long onset and can involve a variety of body sites.[5] Treatment of infection often involves a combination of antifungal drug therapy and surgical excision.

| Ochroconis gallopava | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Sympoventuriaceae |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | O. gallopava |

| Binomial name | |

| Ochroconis gallopava (W.B. Cooke) de Hoog (1983) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy and history

Ochroconis gallopava was first identified as Diplorhinotrichum gallopavum by W.B. Cooke in 1964 and it is renamed as Dactylaria gallopava, by G.C. Bhatt and W.B. Kendrick in 1968, and finally as O. gallopava by de Hoog in 1983.[6] This fungus has many synonyms including Dactylaria constricta, O. constricta, Scolecobasidium constrictum, Diplorhinotrichum gallopavum, Dactylaria gallopava, S. humicola, Heterosporium terrestre, and O. tshawytshae.[7] Phylogenetic analyses indicate that O. gallopava is a member of the family Sympoventuriaceae in the order Venturiales.[8]

Morphology and ecology

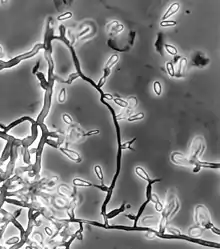

Colonies of Ochroconis gallopava are characteristically flat, dry and tobacco-brown to brownish-black in color.[9] This principle pigment is melanin and it is distributed throughout the conidia and hyphae.[2][5] The fungus also releases a dark brown soluble pigment into agar growth media.[9] Ochroconis gallopava differs from members of genus Dactylaria by the production of septate hyphae and two-celled conidia attached to minute, tooth-like stalks.[2][7]

The fungus occurs diverse habitats including soil, decaying vegetation, and coal waste piles.[2][10] The fungus is thermotolerant and is found in hot springs and nuclear reactors,[1][2] favouring acidic environments.[10]

Diseases

Ochroconis gallopava was thought to cause epidemic fatal encephalitis only in fowls, turkeys, and poults at first, however recently it has been increasingly recognized as a pathogen for human following solid organ transplantation, such as kidney, liver, heart, and lung.[1][2][4][7] The first O. gallopava infection in human was reported in 1986.[2] Prior to 1986, O. gallopava was known as an agent of phaeohyphomycosis and fatal encephalitis mainly in poultry.[2] Even though reports of human infection by this species have increased, O. gallopava remains an extremely uncommon agent of human disease. When it does occur in humans, a wide range of sites may become involved, including the lung, heart, brain, the superficial cutaneous or subcutaneous areas, and other parts of the body.[1] Infection accompanies brain involvement, respiratory tract involvement, pulmonary infections, and skin infections and many others.[2] O. gallopava infection can be divided into fatal disease and manageable disease. Once the fungus penetrates into the central nervous system and involves the brain, the probability of cure by antifungal therapy falls exceedingly.[2][5] When the fungal infection only concerns with systemic involvement except the brain, the probability of cure is higher.[5] In serious infections, the typical entry point is thought to be the respiratory tract.[2] Like other melanized fungi, the clinical presentation of O. gallopava is phaeohyphomycosis characterized by darkly colored lesions in affected tissues,[7] acute or chronic inflammation, microabscesses, fibrosis, granulomas, and necrosis.[2] The onset of symptoms in immunosuppressed individuals after transplantation is very slow, almost several months to years after organ transplantation surgery, but the infection can severely damage the host once it appears.[2] When implicated, the median onset of the infection in organ transplanted patients is 22 months after surgery.[11] Very rarely, O. gallopava infection has been observed in immunologically normal people. Unlike infections in immunocompromised individuals, these cases tend to have a high recovery rate.[12]

Symptoms

Ochroconis gallopava has a proclivity for tissues in the central nervous system, including the brain. Patients with neurological O. gallopava infection can display symptoms of migraine, fever, confusion, seizure, lethargy, neck pain, hemiparesis, and paralysis of the legs or both sides of the body.[2] Respiratory tract infections are associated with milder symptoms such as cough, chest pain, and dyspnea, or may be entirely asymptomatic.[2] Other symptoms have been reported including swelling of shoulder and neck,[11] and skin granules.[2]

Treatment

There are no well known and settled treatments for O. gallopava infection yet. So far, the most effective treatment is early diagnosis of the infection.[1] Also, antifungal drug therapy and surgical excision can be used to treat the infection separately or together.[1][2][3][5] O. gallopava infection treatment widely use antifungal drugs such as amphotericin B, itraconazole, triazole, voriconazole, fluconazole, posaconazole, and many others.[1][2][3] Also, surgical excision can play a role in treatment of O. gallopava infection. This method is useful to remove lesions formed in the affected organ due to phaeohyphomycosis.[7] Surgical resection is especially recommended for removal of CNS lesions.[5] However, both antifungal drugs and surgical excision do not guarantee the perfect cure; there are some reported cases of relapse of the disease.[5] These drugs and surgical methods are the most effective when the fungus is yet disseminated into the brain.[2] Survival rate of the infection varies among individuals depending on the locations of fungus dissemination. Without dissemination into the brain, the chance of survival is greatly increasing, from 33% to almost 100%.[2] However, if the infection is spread throughout the body including the brain, the mortality is 66%.[2][13]

References

- Cardeau-Desangles, I.; Fabre, A.; Cointault, O.; Guitard, J.; Esposito, L.; Iriart, X.; Berry, A.; Valentin, A.; Cassaing, S.; Kamar, N. (1 June 2013). "Disseminated Ochroconis gallopava infection in a heart transplant patient". Transplant Infectious Disease. 15 (3): E115–E118. doi:10.1111/tid.12084. PMID 23601080. S2CID 41597484.

- Shoham, S.; Pic-Aluas, L.; Taylor, J.; Cortez, K.; Rinaldi, M.G.; Shea, Y.; Walsh, T.J. (1 December 2008). "Transplant-associated infections". Transplant-associated Ochroconis Gallopava Infectious Disease. 10 (6): 442–448. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3062.2008.00327.x. PMID 18651872. S2CID 41460732.

- Meriden, Zina; Marr, Kieren A.; Lederman, Howard M.; Illei, Peter B.; Villa, Kathryn; Riedel, Stefan; Carroll, Karen C.; Zhang, Sean X. (1 November 2012). "infection in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease: case report and review of the literature". Medical Mycology. 50 (8): 883–889. doi:10.3109/13693786.2012.681075. PMID 22548237.

- Qureshi, Zubair; Kwak, EJ; Nguyen, MH; Silveira FP (July 2012). "Ochroconis gallopava: a dematiaceous mold causing infections in transplant recipients". Clinical Transplantation. 26 (1): E17–E23. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01528.x. PMID 21955216. S2CID 2687081.

- Singh, N; Chang, FY; Gayowski, T; Marino, IR (March 1997). "Infections due to dematiaceous fungi in organ transplant recipients: case report and review". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 24 (3): 369–74. doi:10.1093/clinids/24.3.369. PMID 9114187.

- MycoBank. "Fungal Databases Nomenclature and Species Banks". International Mycological Association. BioloMICS Net. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- Kralovic, SM; Rhodes, JC (September 1995). "Phaeohyphomycosis caused by Dactylaria (human dactylariosis): report of a case with review of the literature". The Journal of Infection. 31 (2): 107–13. doi:10.1016/s0163-4453(95)92060-9. PMID 8666840.

- Machouart, M.; Samerpitak, K.; de Hoog, G. S.; Gueidan, C. (10 July 2013). "A multigene phylogeny reveals that Ochroconis belongs to the family Sympoventuriaceae (Venturiales, Dothideomycetes)". Fungal Diversity. 65 (1): 77–88. doi:10.1007/s13225-013-0252-7. S2CID 15847954.

- G. S. de Hoog, Guarro J; Gene J; Figueras MJ (2000). Atlas of clinical fungi (2. ed.). Utrecht: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures [u.a.] ISBN 978-90-70351-43-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tansey, MR; Brock, TD (16 March 1973). "Dactylaria gallopava, a Cause of Avian Encephalitis, in Hot Spring Effluents, Thermal Soils and Self-heated Coal Waste Piles". Nature. 242 (5394): 202–203. Bibcode:1973Natur.242..202T. doi:10.1038/242202a0. PMID 4550022. S2CID 2170752.

- Mazur, Joseph E. (1 February 2001). "A Case Report of a Dactylaria Fungal Infection in a Lung Transplant Patient<xref rid="AFF1">*</xref>". Chest. 119 (2): 651–653. doi:10.1378/chest.119.2.651. PMID 11171754.

- Hollingsworth, J. W.; Shofer, S.; Zaas, A. (20 August 2007). "Successful Treatment of Ochroconis gallopavum Infection in an Immunocompetent Host". Infection. 35 (5): 367–369. doi:10.1007/s15010-007-6054-7. PMID 17710372. S2CID 26368446.

- Brokalaki, E.I.; Sommerwerck, U.; von Heinegg, E.H.; Hillen, U. (1 November 2012). "Ochroconis Gallopavum Infection in a Lung Transplant Recipient: Report of a Case". Transplantation Proceedings. 44 (9): 2778–2780. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.09.007. PMID 23146522.