Octave

In music, an octave (Latin: octavus: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason)[2] is the interval between one musical pitch and another with double its frequency. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been referred to as the "basic miracle of music", the use of which is "common in most musical systems".[3] The interval between the first and second harmonics of the harmonic series is an octave.

| Inverse | unison |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Other names | - |

| Abbreviation | P8 |

| Size | |

| Semitones | 12 |

| Interval class | 0 |

| Just interval | 2:1[1] |

| Cents | |

| Equal temperament | 1200[1] |

| Just intonation | 1200[1] |

In Western music notation, notes separated by an octave (or multiple octaves) have the same name and are of the same pitch class.

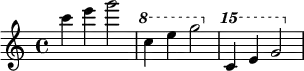

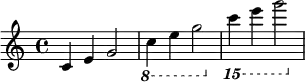

To emphasize that it is one of the perfect intervals (including unison, perfect fourth, and perfect fifth), the octave is designated P8. Other interval qualities are also possible, though rare. The octave above or below an indicated note is sometimes abbreviated 8a or 8va (Italian: all'ottava), 8va bassa (Italian: all'ottava bassa, sometimes also 8vb), or simply 8 for the octave in the direction indicated by placing this mark above or below the staff.

Explanation and definition

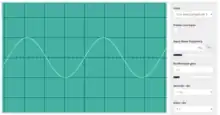

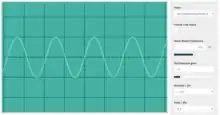

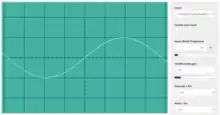

An octave is the interval between one musical pitch and another with double or half its frequency. For example, if one note has a frequency of 440 Hz, the note one octave above is at 880 Hz, and the note one octave below is at 220 Hz. The ratio of frequencies of two notes an octave apart is therefore 2:1. Further octaves of a note occur at times the frequency of that note (where n is an integer), such as 2, 4, 8, 16, etc. and the reciprocal of that series. For example, 55 Hz and 440 Hz are one and two octaves away from 110 Hz because they are +1⁄2 (or ) and 4 (or ) times the frequency, respectively.

The number of octaves between two frequencies is given by the formula:

C5, an octave above middle C. The frequency is twice that of middle C (523 Hz).

C5, an octave above middle C. The frequency is twice that of middle C (523 Hz). C3, an octave below middle C. The frequency is half that of middle C (131 Hz).

C3, an octave below middle C. The frequency is half that of middle C (131 Hz).

Music theory

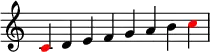

Most musical scales are written so that they begin and end on notes that are an octave apart. For example, the C major scale is typically written C D E F G A B C (shown below), the initial and final C's being an octave apart.

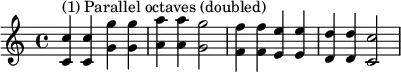

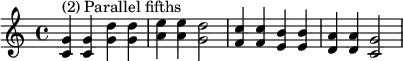

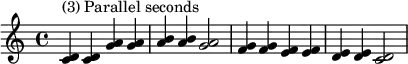

Because of octave equivalence, notes in a chord that are one or more octaves apart are said to be doubled (even if there are more than two notes in different octaves) in the chord. The word is also used to describe melodies played in parallel one or more octaves apart (see example under Equivalence, below).

While octaves commonly refer to the perfect octave (P8), the interval of an octave in music theory encompasses chromatic alterations within the pitch class, meaning that G♮ to G♯ (13 semitones higher) is an Augmented octave (A8), and G♮ to G♭ (11 semitones higher) is a diminished octave (d8). The use of such intervals is rare, as there is frequently a preferable enharmonically-equivalent notation available (minor ninth and major seventh respectively), but these categories of octaves must be acknowledged in any full understanding of the role and meaning of octaves more generally in music.

Notation

Octave of a pitch

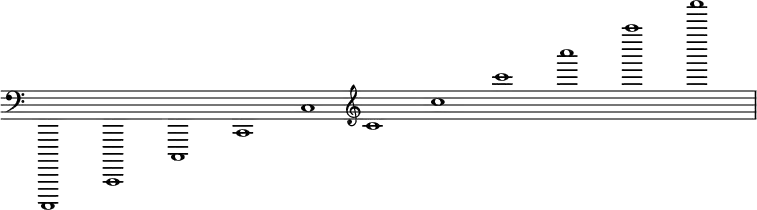

Octaves are identified with various naming systems. Among the most common are the scientific, Helmholtz, organ pipe, and MIDI note systems. In scientific pitch notation, a specific octave is indicated by a numerical subscript number after note name. In this notation, middle C is C4, because of the note's position as the fourth C key on a standard 88-key piano keyboard, while the C an octave higher is C5.

Scientific C−1 C0 C1 C2 C3 C4 C5 C6 C7 C8 C9 Helmholtz C,,, C,, C, C c c' c'' c''' c'''' c''''' c'''''' Organ 64 Foot 32 Foot 16 Foot 8 Foot 4 Foot 2 Foot 1 Foot 3 Line 4 Line 5 Line 6 Line Name Dbl Contra Sub Contra Contra Great Small 1 Line 2 Line 3 Line 4 Line 5 Line 6 Line MIDI Note 0 12 24 36 48 60 72 84 96 108 120

Ottava alta and bassa

The notation 8a or 8va is sometimes seen in sheet music, meaning "play this an octave higher than written" (all' ottava: "at the octave" or all' 8va). 8a or 8va stands for ottava, the Italian word for octave (or "eighth"); the octave above may be specified as ottava alta or ottava sopra). Sometimes 8va is used to tell the musician to play a passage an octave lower (when placed under rather than over the staff), though the similar notation 8vb (ottava bassa or ottava sotto) is also used. Similarly, 15ma (quindicesima) means "play two octaves higher than written" and 15mb (quindicesima bassa) means "play two octaves lower than written."

The abbreviations col 8, coll' 8, and c. 8va stand for coll'ottava, meaning "with the octave", i.e. to play the notes in the passage together with the notes in the notated octaves. Any of these directions can be cancelled with the word loco, but often a dashed line or bracket indicates the extent of the music affected.[4]

Equivalence

After the unison, the octave is the simplest interval in music. The human ear tends to hear both notes as being essentially "the same", due to closely related harmonics. Notes separated by an octave "ring" together, adding a pleasing sound to music. The interval is so natural to humans that when men and women are asked to sing in unison, they typically sing in octave.[5]

For this reason, notes an octave apart are given the same note name in the Western system of music notation—the name of a note an octave above A is also A. This is called octave equivalence, the assumption that pitches one or more octaves apart are musically equivalent in many ways, leading to the convention "that scales are uniquely defined by specifying the intervals within an octave".[6] The conceptualization of pitch as having two dimensions, pitch height (absolute frequency) and pitch class (relative position within the octave), inherently include octave circularity.[6] Thus all C♯s (or all 1s, if C = 0), any number of octaves apart, are part of the same pitch class.

Octave equivalence is a part of most advanced musical cultures, but is far from universal in "primitive" and early music.[7][8] The languages in which the oldest extant written documents on tuning are written, Sumerian and Akkadian, have no known word for "octave". However, it is believed that a set of cuneiform tablets that collectively describe the tuning of a nine-stringed instrument, believed to be a Babylonian lyre, describe tunings for seven of the strings, with indications to tune the remaining two strings an octave from two of the seven tuned strings.[9] Leon Crickmore recently proposed that "The octave may not have been thought of as a unit in its own right, but rather by analogy like the first day of a new seven-day week".[10]

Monkeys experience octave equivalence, and its biological basis apparently is an octave mapping of neurons in the auditory thalamus of the mammalian brain.[11] Studies have also shown the perception of octave equivalence in rats,[12] human infants,[13] and musicians[14] but not starlings,[15] 4–9-year-old children,[16] or non-musicians.[14][6]

See also

- Blind octave – Music composition and performance technique

- Decade – Unit for measuring ratios on a logarithmic scale

- Eight-foot pitch – Standard pitch designation

- Octave band – Base 2 logarithmically-spaced frequency bands

- Octave species – Classification of musical key or scale in ancient Greek music theory

- One-third octave

- Pitch circularity – Fixed series of tones that appear to ascend or descend endlessly in pitch

- Pseudo-octave

- Pythagorean interval – Musical interval

- Short octave

- Solfège – Music teaching method

References

- Duffin, Ross W. (2008). How equal temperament ruined harmony : (and why you should care) (First published as a Norton paperback. ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-393-33420-3. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- William Smith & Samuel Cheetham (1875). A Dictionary of Christian Antiquities. London: John Murray. ISBN 9780790582290. Archived from the original on 2016-04-30.

- Cooper, Paul (1973). Perspectives in Music Theory: An Historical-Analytical Approach, p. 16. ISBN 0-396-06752-2.

- Prout, Ebenezer & Fallows, David (2001). "All'ottava". In Sadie, Stanley & Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- "Music". Vox Explained. Event occurs at 12:50. Retrieved 2018-11-01.

When you ask men and women to sing in unison, what typically happens is they actually sing an octave apart.

- Burns, Edward M. (1999). "Intervals, Scales, and Tuning". In Diana Deutsch (ed.). The Psychology of Music (2nd ed.). San Diego: Academic Press. p. 252. ISBN 0-12-213564-4.

- e.g., Nettl, 1956; Sachs, C[urt]. and Kunst, J[aap]. (1962). In The Wellsprings of Music, ed. Kunst, J. The Hague: Marinus Nijhoff.

- e.g., Nettl, 1956; Sachs, C. and Kunst, J. (1962). Cited in Burns 1999, p. 217.

- Clint Goss (2012). "Flutes of Gilgamesh and Ancient Mesopotamia". Flutopedia. Archived from the original on 2012-06-28. Retrieved 2012-01-08.

- Leon Crickmore (2008). "New Light on the Babylonian Tonal System". ICONEA 2008: Proceedings of the International Conference of Near Eastern Archaeomusicology, Held at the British Museum, December 4–6, 2008. 24: 11–22.

- "The mechanism of octave circularity in the auditory brain Archived 2010-04-01 at the Wayback Machine", Neuroscience of Music.

- Blackwell & Schlosberg 1943.

- Demany & Armand 1984.

- Allen 1967.

- Cynx 1993.

- Sergeant 1983.

Sources

- Allen, David. 1967. "Octave Discriminability of Musical and Non-Musical Subjects". Psychonomic Science 7:421–22.

- Blackwell, H. R., & H. Schlosberg. 1943. "Octave Generalization, Pitch Discrimination, and Loudness Thresholds in the White Rat". Journal of Experimental Psychology 33:407–419.

- Cynx, Jeffrey. 1996. "Neuroethological Studies on How Birds Discriminate Song". In Neuroethology of Cognitive and Perceptual Processes, edited by C. F. Moss and S. J. Shuttleworth, 63. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Demany, Laurent, and Françoise Armand. 1984. "The Perceptual Reality of Tone Chroma in Early Infancy". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 76:57–66.

- Sergeant, Desmond. 1983. "The Octave: Percept or Concept?" Psychology of Music 11, no. 1:3–18.