Odjak of Algiers

The Odjak of Algiers was a unit of the Algerian army.[1] It was a highly autonomous part of the Janissary Corps, acting completely independently from the rest of the corps,[2] similar to the relationship between Algiers and the Sublime Porte.[3] Led by an Agha, they also took part in the country's internal administration and politics, ruling the country for several years.[4] They acted as a defense unit, a Praetorian Guard,[5] and an instrument of repression until 1817.

| Odjak of Algiers | |

|---|---|

| Ujaq | |

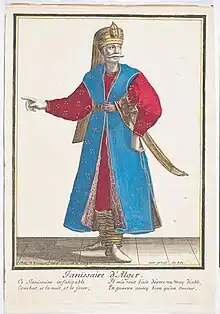

A Janissary of Algiers | |

| Active | 1518-1830 |

| Disbanded | De jure 1830, De facto 1837 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | Agha of the Odjak |

| Size | 12,000 (1600) 7,000 (1750) 4,000 (1800) |

| Main location | Algiers |

| Equipment | Initially: Equipment by the Ottoman Empire After 1710: Nimcha, Kabyle musket, and other locally made weapons |

| Engagements | Algiers expedition (1541) Tuggurt Expedition (1552) French-Algerian War 1681–88 Battle of Moulouya Tunisian-Algerian Wars Algerine civil war (1710) Invasion of Algiers (1775) Invasion of Algiers in 1830 Battle of Constantine |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Ibrahim Agha |

Ethnic composition

From the Ottoman Empire

The majority of the unit during the 16th to 18th century were composed of "Turks". These "Turks" were not strictly or mainly Turkish. They included Albanians, Greeks, Serbs, Kurds and Armenians.[6] They were recruited in the Ottoman Empire, or in some cases from immigrants. After the 18th century most Janissaries from the Ottoman Empire were mercenaries.

Kouloughlis

Kouloughlis were people of mixed Ottoman and Moorish origins. In 1629 the Kouloughlis, allied with many other local tribes, attempted to drive out the Odjak and the janissaries. They failed and were expelled. In 1674, they were allowed to join the corps, but only first generation kouloughlis (direct sons of Turks). In 1694, this was relaxed, and all Kouloughlis were allowed to join the odjak.[7] By the 18th and 19th century the Kouloughlis formed the majority in the corps.

Algerian Moors and Arabs

Despite initially not being allowed to join the army, as time passed, and relations became more and more distant between the Ottoman Empire and the Regency,[3] importation of troops became more and more problematic. Initially, some locals were allowed to join the odjak as garrison auxiliaries. This became more and more common, but only in isolated areas. As many Between 1699 and 1701, out of 40 cases of janissaries whose origins are mentioned, 5 had been recruited among the Algerians,[8] but these were in mostly rural areas. In reality, the corps was still overwhelmingly Turkish. After a coup by Ali Chauch the Odjak was weakened, and the Dey-Pacha had far more authority than before.[9] He weakened the janissaries, and forced them to lax their procedures. As time passed, these procedures were more and more lax. As the Odjak was the main force outside of the unreliable Arab-Berber tribal levy whom were in a lot of cases regarded as unloyal,[10] it was important not to recruit people who would have tribal loyalties. Thus many Algerian orphans and criminals were recruited into the Odjak. By 1803 every 17th janissary was of Algerian origins.[8]

By 1828 out of the total 14,000 Ujaq janissaries, 2,000 were Algerians meaning that every 7th Janissary was of fully Algerian origins.[11]

Renegades

Renegades were also allowed into the corps, although their exact number isn't known and was probably low.

Turmoil in 1817

After a period of stagnation and military defeat Algiers was severely weakened. After losing the Barbary Wars and the Bombardment of Algiers, the Odjak sprang into action and killed the ruling dey, Omar Agha. In 1817 Ali Khodja carried put a coup following a decisive defeat. The Turk janissaries attempted a coup against whom Ali Khodja raised the Kouloughli janissaries, and allied Berber tribes such as the Igawawen. The Turks were defeated and slaughtered and the rest were sent back to the Ottoman provinces.

References

- "L'Odjak d'Alger". www.algerie-ancienne.com. Archived from the original on 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil M.; Abun-Nasr, Abun-Nasr, Jamil Mirʻi (1987-08-20). A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33767-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Association, American Historical (1918). General Index to Papers and Annual Reports of the American Historical Association, 1884-1914. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Brenner, William J. (2016-01-29). Confounding Powers: Anarchy and International Society from the Assassins to Al Qaeda. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-10945-2.

- HistoireDuMonde.net. "Histoire du monde.net". histoiredumonde.net (in French). Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- Morell, John Reynell (1854). Algeria: The Topography and History, Political, Social, and Natural, of French Africa. N. Cooke.

- Extract from Tachrifat , reported by Pierre Boyer, 1970, page 84

- Shuval, Tal (2013-09-30), "Chapitre II. La caste dominante", La ville d’Alger vers la fin du XVIIIe siècle : Population et cadre urbain, Connaissance du Monde Arabe, Paris: CNRS Éditions, pp. 57–117, ISBN 978-2-271-07836-0, retrieved 2021-01-12

- Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne (in French). 1834.

- Hall, J. Peter (2020-09-04). A Narrative Tale of Morocco. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-7960-9286-8.

- Abou-Khamseen, Mansour Ahmad (1983). The First French-Algerian War (1830-1848): A Reappraisal of the French Colonial Venture and the Algerian Resistance. University of California, Berkeley.