Oedipus (Voltaire play)

Oedipus (French: Œdipe) is a tragedy by the French dramatist and philosopher Voltaire that was first performed in 1718.[1] It was his first play and the first literary work for which he used the pen-name Voltaire (his real name was François-Marie Arouet).

| Oedipus | |

|---|---|

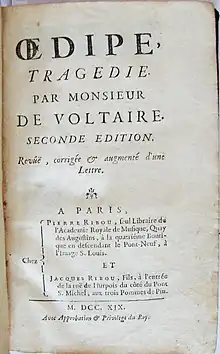

Title page of the second edition | |

| Written by | Voltaire |

| Date premiered | 18 November 1718 |

| Place premiered | Comédie-Française, Paris |

| Original language | French |

| Subject | Myth of Oedipus |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Setting | Thebes |

Composition

Voltaire completed the play in 1717 during his 11-month imprisonment. In a letter of 1731 Voltaire wrote that when he wrote the play he was "full of my readings of the ancient authors [...] I knew very little of the theater in Paris."[2] In adapting Sophocles' Athenian tragedy Oedipus Rex, Voltaire attempted to rationalise the plot and motivation of its characters.[3] In a letter of 1719 he indicated that he found it improbable that the murder of Laius had not been investigated earlier and that Oedipus should take so long to understand the oracle's clear pronouncement.[4] Voltaire adds a subplot concerning the love of Philoctète for Jocaste.[4] He also reduces the prominence of the theme of incest.[5]

Critical reception

Oedipe premièred on 18 November 1718 at the Comédie-Française, during his first period of exile at Châtenay-Malabry. Quinault-Dufresne played Oedipus, and Charlotte Desmares, Jocaste. The Régent was present at the première and congratulated Voltaire for his success. The Regent was long rumored to have an incestuous relation with his elder daughter, Marie Louise Élisabeth d'Orléans, Duchess of Berry. Voltaire had been arrested and sent to the Bastille in May 1717 after telling a police informer that the Duchess was pregnant and secluding herself in her castle of La Muette pending her delivery.[6] Rumors of Philippe's incestuous relationship with his daughter had made Arouet's play controversial long before it was performed.[7] The première was also attended by the Duchess of Berry who entered in royal style escorted by the ladies of her court and her guards. The Royal Altess was dazzlingly beautiful in her sumptuous sack-back gown, which highlighted her ample bosom while concealing the curves of her body. But when spectators looked at the volume of the loose-fitting gown concealing the corpulence of the princess, they couldn't fail to notice that her plump waistline had grown considerably bigger in recent weeks, suggesting she was once again carrying in her womb the fruit of her debauchery. Berry's conspicuous condition inspired saucy comments by spectators about the amours of Oedipus (the Regent) and Jocasta (Berry) now visibly big with Eteocles. The presence of the ill-reputed princess thus contributed to the public success of the play.[8]

On February 11, 1719, the Duchess of Berry attended another performance of Œdipe, played in honor of her nephew Louis XV, at the Louvre Palace. She sat next to the little king. The theater room was packed, and the heat made the princess feel ill and faint when a theatrical allusion to Jocasta's incestuous maternity was loudly applauded by the audience. Malicious tongues immediately whispered that "Berry-Jocasta" had just gone into labor and would give birth to Eteocles in the middle of the play, but a window was opened and the mother-to-be recovered from her fainting spell.[9] Despite her scandalous pregnancy, the Duchess of Berry attended Voltaire's play five times. The fecund young widow was said to be attracted to Quinault-Dufresne's beauty, leading her to defy public opinion and admire the actor's physique.[10] The production ran for 45 performances and received great critical acclaim that marked the start of Voltaire's success in his theatrical career. It constituted "the greatest dramatic success of eighteenth century France".[11] It was revived on 7 May 1723 with Le Couvreur and Quinault-Dufresne and remained in the répertoire of Comédie-Française until 1852.

References

- Banham (1998, 1176) and Vernant and Vidal-Naquet (1988, 373).

- Quoted by Vernant and Vidal-Naquet (1988, 373).

- Burian (1997, 240, 245).

- Burian (1997, 245).

- Burian (1997, 246).

- Jean-Michel Raynaud, Voltaire soi-disant, Presses Universitaires de Lille, 1983, vol.1, p.289.

- Jay Caplan, In the King's Wake : Post-Absolutist Culture in France. University of Chicago Press, 1994, p.50-51.

- Philippe Erlanger, Le Régent, 1985, p.241.

- Édouard de Barthélémy, Les filles du Régent, Paris : Firmin Didot frères, 1874, vol. 1 p.227. The Duchess of Berry gave birth to a still-born daughter on 2 April 1719. The health ruined by her harrowing delivery, she died on 21 July 1719 at La Muette. The autopsy revealed she was already two months pregnant.

- Jean-Claude Montanier, D'Allainval (L'Abbé) Auteur dramatique (1696-1753). Biographie dévoilée et l'intégralité de son Théâtre, 2021, p.186; 'Capefigue (M., Jean Baptiste Honoré Raymond), Philippe d'Orléans, régent de France (1715-1723), 1838, vol.1, p. 394

- Vernant and Vidal-Naquet (1988, 373).

Sources

- Banham, Martin, ed. 1998. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-43437-8.

- Burian, Peter. 1997. "Tragedy Adapted for Stages and Screens: the Renaissance to the Present." The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy. Ed. P. E. Easterling. Cambridge Companions to Literature ser. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. 228–283. ISBN 0-521-42351-1.

- Vernant, Jean-Pierre, and Pierre Vidal-Naquet. 1988. Myth and Tragedy in Ancient Greece. Trans. Janet Lloyd. New York: Zone Books, 1990. ISBN 0-942299-19-1. Trans. of Mythe et Tragédie en Grèce Ancienne (Librarie François Maspero, 1972) and Mythe et Tragédie en Grèce Ancienne Deux (Editions La Découverte, 1986).