Esophagitis

Esophagitis, also spelled oesophagitis, is a disease characterized by inflammation of the esophagus. The esophagus is a tube composed of a mucosal lining, and longitudinal and circular smooth muscle fibers. It connects the pharynx to the stomach; swallowed food and liquids normally pass through it.[1]

| Esophagitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Oesophagitis |

| |

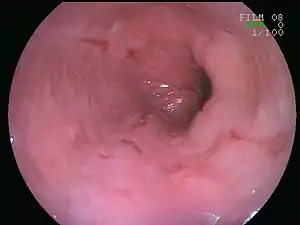

| An esophageal ulcer visualized by esophagoscopy: the reddened area at 10 o'clock on the surface of the mucosa. | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Complications | Cancer |

Esophagitis can be asymptomatic; or can cause epigastric and/or substernal burning pain, especially when lying down or straining; and can make swallowing difficult (dysphagia). The most common cause of esophagitis is the reverse flow of acid from the stomach into the lower esophagus: gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).[2]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of esophagitis include:[2]

- Heartburn – a burning sensation in the lower mid-chest

- Nausea

- Dysphagia – swallowing is painful, with difficulty passing or inability to pass food through the esophagus

- Vomiting (emesis)

- Abdominal pain

- Cough

Complications

If the disease remains untreated, it can cause scarring and discomfort in the esophagus. If the irritation is not allowed to heal, esophagitis can result in esophageal ulcers. Esophagitis can develop into Barrett's esophagus and can increase the risk of esophageal cancer.[3]

Causes

Infectious esophagitis cannot be spread. However, infections can be spread by those who have infectious esophagitis. Esophagitis can develop due to many causes. GERD is the most common cause of esophagitis because of the backflow of acid from the stomach, which can irritate the lining of the esophagus.

Other causes include:

- Medicines – Can cause esophageal damage that can lead to esophageal ulcers

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) – aspirin, naproxen sodium, and ibuprofen. Known to irritate the GI tract.

- Antibiotics – doxycycline and tetracycline

- Quinidine

- Bisphosphonates – used to treat osteoporosis

- Steroids

- Potassium chloride

- Chemical injury by alkaline or acid solutions

- Physical injury resulting from nasogastric tubes.

- Alcohol use disorder – Can wear down the lining of the esophagus.

- Crohn's disease – a type of IBD and an autoimmune disease that can cause esophagitis if it attacks the esophagus.

- Stress – Can cause higher levels of acid reflux

- Radiation therapy - Can affect the immune system.

- Allergies (food, inhalants) – Allergies can stimulate eosinophilic esophagitis.

- Infection - People with an immunodeficiencies have a higher chance of developing esophagitis.

- Vitamins and supplements (iron, vitamin C, and potassium) – Supplements and minerals can be hard on the GI tract.

- Vomiting – Acid can irritate esophagus.

- Hernias – A hernia can poke through the diaphragm muscle and can inhibit the stomach acid and food from draining quickly.

- Surgery

- Eosinophilic esophagitis, a more chronic condition with a theorized autoimmune component

Mechanism

The esophagus is a muscular tube made of both voluntary and involuntary muscles. It is responsible for peristalsis of food. It is about 8 inches long and passes through the diaphragm before entering the stomach. The esophagus is made up of three layers: from the inside out, they are the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa. The mucosa, the inner most layer and lining of the esophagus, is composed of stratified squamous epithelium, lamina propria, and muscularis mucosae. At the end of the esophagus is the lower esophageal sphincter, which normally prevents stomach acid from entering the esophagus.

If the sphincter is not sufficiently tight, it may allow acid to enter the esophagus, causing inflammation of one or more layers. Esophagitis may also occur if an infection is present, which may be due to bacteria, viruses, or fungi; or by diseases that affect the immune system.[4]

Irritation can be caused by GERD, vomiting, surgery, medications, hernias, and radiation injury.[4] Inflammation can cause the esophagus to narrow, which makes swallowing food difficult and may result in food bolus impaction.

Diagnosis

Esophagitis can be diagnosed by upper endoscopy, biopsy, upper GI series (or barium swallow), and laboratory tests.[4]

An upper endoscopy is a procedure to look at the esophagus by using an endoscope. While looking at the esophagus, the doctor is able to take a small biopsy. The biopsy can be used to confirm inflammation of the esophagus.

An upper GI series uses a barium contrast, fluoroscopy, and an X-ray. During a barium X-ray, a solution with barium or pill is taken before getting an X-ray. The barium makes the organs more visible and can detect if there is any narrowing, inflammation, or other abnormalities that can be causing the disease. The upper GI series can be used to find the cause of GI symptoms. An esophagram is if only the throat and esophagus are looked at.[5]

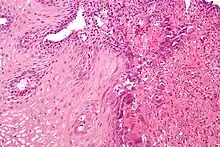

Laboratory tests can be done on biopsies removed from the esophagus and can help determine the cause of the esophagitis. Laboratory tests can help diagnose a fungal, viral, or bacterial infection. Scanning for white blood cells can help diagnose eosinophil esophagitis.

Some lifestyle indicators for this disease include stress, unhealthy eating, smoking, drinking, family history, allergies, and immunodeficiency.

Types

Reflux esophagitis

Although it usually assumed that inflammation from acid reflux is caused by the irritant action on the mucosa by hydrochloric acid, one study suggests that the pathogenesis of reflux esophagitis may be cytokine-mediated.[6]

Infectious esophagitis

Esophagitis happens due to a viral, fungal, parasitic or bacterial infection. More likely to happen to people who have an immunodeficiency. Types include:

Fungal

Viral

Drug-induced esophagitis

Damage to the esophagus due to medications. If the esophagus is not coated or if the medicine is not taken with enough liquid, it can damage the tissues.

Eosinophilic esophagitis

Eosinophilic esophagitis is caused by a high concentration of eosinophils in the esophagus. The presence of eosinophils in the esophagus may be due to an allergen and is often correlated with GERD. The direction of cause and effect between inflammation and acid reflux is poorly established, with recent studies (in 2016) hinting that reflux does not cause inflammation.[6] This esophagitis can be triggered by allergies to food or to inhaled allergens. This type is still poorly understood.

Lymphocytic esophagitis

Lymphocytic esophagitis is a rare and poorly understood entity associated with an increased amount of lymphocytes in the lining of the esophagus.[1] It was first described in 2006. Disease associations may include Crohn's disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease and coeliac disease. It causes similar changes on endoscopy as eosinophilic esophagitis including esophageal rings, narrow-lumen esophagus, and linear furrows.

Caustic esophagitis

Caustic esophagitis is the damage of tissue via chemical origin. This occasionally occurs through occupational exposure (via breathing of fumes that mix into the saliva which is then swallowed) or through pica. It occurred in some teenagers during the fad of intentionally eating Tide pods.

By severity

The severity of reflux esophagitis is commonly classified into four grades according to the Los Angeles Classification:[7][8]

| Grade A | One or more mucosal breaks < 5 mm in maximal length |

| Grade B | One or more mucosal breaks > 5mm, but without continuity across mucosal folds |

| Grade C | Mucosal breaks continuous between ≥ 2 mucosal folds but involving less than 75% of the esophageal circumference |

| Grade D | Mucosal breaks involving more than 75% of esophageal circumference |

Prevention

Since there can be many causes underlying esophagitis, it is important to try to find the cause to help to prevent esophagitis. To prevent reflux esophagitis, avoid acidic foods, caffeine, eating before going to bed, alcohol, fatty meals, and smoking. To prevent drug-induced esophagitis, drink plenty of liquids when taking medicines, take an alternative drug, and do not take medicines while lying down, before sleeping, or too many at one time. Esophagitis is more prevalent in adults and does not discriminate.

Treatment

Lifestyle changes

Losing weight, stop smoking and alcohol, lowering stress, avoid sleeping/lying down after eating, raising the head of the bed, taking medicines correctly, avoiding certain medications, and avoiding foods that cause the reflux that might be causing the esophagitis.[9]

Antacids

To treat reflux esophagitis, over the counter antacids, medications that reduce acid production (H-2 receptor blockers), and proton pump inhibitors are recommended to help block acid production and to let the esophagus heal. Some prescription medications to treat reflux esophagitis include higher dose H-2 receptor blockers, proton pump inhibitors, and prokinetics, which help with the emptying of the stomach. However prokinetics are no longer licensed for GERD because their evidence of efficacy is poor, and following a safety review, licensed use of domperidone and metoclopramide is now restricted to short-term use in nausea and vomiting only.[10]

For subtypes

To treat eosinophilic esophagitis, avoiding any allergens that may be stimulating the eosinophils is recommended. As for medications, proton pump inhibitors and steroids can be prescribed. Steroids that are used to treat asthma can be swallowed to treat eosinophil esophagitis due to nonfood allergens. The removal of food allergens from the diet is included to help treat eosinophilic esophagitis.

For infectious esophagitis, medicine is prescribed based on what type of infection is causing the esophagitis. These medicines are prescribed to treat bacterial, fungal, viral, and/or parasitic infections.

Procedures

- An endoscopy can be used to remove ill fragments.

- Surgery can be done to remove the damaged part of the esophagus.[4]

- For reflux esophagitis, a fundooplication can be done to help strengthen the lower esophageal sphincter from allowing backflow of the stomach into the esophagus.

- For esophageal stricture, a gastroenterologist can perform a dilation of the esophagus.

As of 2020 evidence for magnetic sphincter augmentation is poor.[11]

Prognosis

The prognosis for a person with esophagitis depends on the underlying causes and conditions. If a patient has a more serious underlying cause such as a digestive system or immune system issue, it may be more difficult to treat. Normally, the prognosis would be good with no serious illnesses. If there are more causes than one, the prognosis could move to fair.

Terminology

The term is from Greek οἰσοφάγος "gullet" and -itis "inflammation".

References

- "Esophagitis – Symptoms and causes – Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "Esophagitis-Topic Overview". WebMD. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "Esophagitis". Johns Hopkins Medicine. 19 November 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- "Understanding Esophagitis". WebMD. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- "Upper Gastrointestinal (UGI) Series". WebMD. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "Inflammation, Not Acid, Cause of GERD, Study Suggests".

- Farivar M. "Los Angeles Classification of Esophagitis". webgerd.com. Archived from the original on 2015-01-30. Retrieved 2010-10-27. In turn citing: Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, et al. (August 1999). "Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification". Gut. 45 (2): 172–80. doi:10.1136/gut.45.2.172. PMC 1727604. PMID 10403727.

- Laparoscopic bariatric surgery, Volume 1. William B. Inabnet, Eric J. DeMaria, Sayeed Ikramuddin. ISBN 0-7817-4874-7.

- "Esophagitis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), 2013. Metoclopramide: risk of neurological adverse effects. Drug Safety Update 7 (1), S2. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, 2014. Domperidone: risks of cardiac side effects. Drug Safety Update 7 (10), A1. Moayyedi, P., Santana, J., Khan, M., et al., 2011. Medical treatments in the short-term management of relux oesophagitis. Cochrane DB Syst. Rev. 2011 (2), Art. No. CD003244.

- Kirkham, EN; Main, BG; Jones, KJB; Blazeby, JM; Blencowe, NS (January 2020). "Systematic review of the introduction and evaluation of magnetic augmentation of the lower oesophageal sphincter for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease". The British Journal of Surgery. 107 (1): 44–55. doi:10.1002/bjs.11391. PMC 6972716. PMID 31800095.