Officer of the United States

An officer of the United States is a functionary of the executive or judicial branches of the federal government of the United States to whom is delegated some part of the country's sovereign power. The term officer of the United States is not a title, but a term of classification for a certain type of official.

Under the Appointments Clause of the Constitution, the principal officers of the U.S., such as federal judges, ambassadors, and "public Ministers" (Cabinet members) are appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate, but Congress may vest the appointment of inferior officers to the president, courts, or federal department heads. Civilian officers of the U.S. are entitled to preface their names with the honorific style "the Honorable" for life, but this rarely occurs. Officers of the U.S. should not be confused with employees of the U.S.; the latter are more numerous and lack the special legal authority of the former.

Background

Origin and definition

The Appointments Clause of the Constitution (Article II, section 2, clause 2), empowers the President of the United States to appoint "Officers of the United States" with the "advice and consent" of the U.S. Senate. The same clause also allows lower-level officials to be appointed without the advice and consent process.[1][2]

... he shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law: but the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.

The Framers of the U.S. Constitution understood the role of high officers specially imbued with certain authority to act on behalf of the head of state within the context of their earlier experience with the British Crown. Day-to-day administration of the British Government was based on persons "holding sovereign authority delegated from the King that enabled them in conducting the affairs of government to affect the people." This was an extension of the general common-law rule that "where one man hath to do with another's affairs against his will, and without his leave, that this is an office, and he who is in it, is an officer."[3]

According to an April 2007 memorandum opinion by the U.S. Department of Justice's Office of Legal Counsel, addressed to the general counsels of the executive branch, defined "officer of the United States" as:[3]

a position to which is delegated by legal authority a portion of the sovereign power of the federal government and that is 'continuing' in a federal office subject to the Constitution's Appointment Clause. A person who would hold such a position must be properly made an 'officer of the United States' by being appointed pursuant to the procedures specified in the Appointments Clause.

Several officers of the U.S. are included in the presidential line of succession and are empowered to become acting president in situations where neither the president nor the vice president is able to discharge their functions.[4] Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 of the Constitution authorizes Congress to enact such a statute.[5]

The difference between an officer of the United States and an Employee of the United States, therefore, ultimately rests on whether the office held has been explicitly delegated part of the "sovereign power of the United States". Delegation of "sovereign power" means possession of the authority to commit the federal government of the U.S. to some legal obligation, such as by signing a contract, executing a treaty, interpreting a law, or issuing military orders. A federal judge, for instance, has been delegated part of the "sovereign power" of the U.S. to exercise; while a letter carrier for the U.S. Postal Service has not. Some very prominent title-holders, including the White House Chief of Staff, the White House Press Secretary and most other high-profile presidential staff assistants, are only employees of the U.S. as they have no authority to exercise the sovereign power of the federal government.[3][1]

Military officers and secondary appointments

In addition to civilian officers of the U.S., persons who hold military commissions are also considered officers of the U.S. While not explicitly defined as such in the Constitution, this fact is implicit in its structure. According to a 1996 opinion by then-Assistant Attorney General Walter Dellinger of the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel, "even the lowest ranking military or naval officer is a potential commander of U.S. armed forces in combat—and, indeed, is in theory a commander of large military or naval units by presidential direction or in the event of catastrophic casualties among his or her superiors."[6] The officer's authority to command the forces of the U.S. draws its legitimacy from the president himself as "Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States"; the president cannot reasonably be expected to command every soldier, or any soldier, in the field and so delegates his authority to command to officers he commissions.[3]

Commissioned officers of the eight uniformed services of the U.S.—the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, Coast Guard, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Corps, and Public Health Service Commissioned Corps—are all officers of the U.S. Under current law, the Senate does not require the commissions of all military officers to be confirmed; however, anyone being first promoted to major in the Regular Army, Marine Corps, Air Force, or Space Force, or lieutenant commander in the Regular Navy, does require such confirmation. Additionally, military officers promoted in the Reserves to colonel (or captain in the Navy) also require Senate confirmation. This results in hundreds of promotions that annually must be confirmed by the Senate, though these are typically confirmed en masse without individual hearings.[7][3]

Finally, some persons not appointed by the president but, instead, appointed by persons or bodies who are, themselves, appointed by the president may be officers of the United States if defined as such under the law. Examples include U.S. magistrate judges, who are appointed by U.S. district courts, and the U.S. postmaster general, who is appointed by the Board of Governors of the U.S. Postal Service, which, in turn, is appointed by the president.[3][8]

Ineligibility Clause

Members of the U.S. Congress—the legislative branch of the U.S. government—are not "officers of the United States" and cannot simultaneously serve in Congress and as an officer of the U.S. under the "Ineligibility Clause" (also called the "Incompatibility Clause") of the Constitution (Article 1, Section 6, Clause 2). This provision states:[3]

No Senator or Representative shall, during the Time for which he was elected, be appointed to any civil Office under the Authority of the United States, which shall have been created, or the Emoluments whereof shall have been increased during such time; and no Person holding any Office under the United States, shall be a Member of either House during his Continuance in Office.

The question of whether the Ineligibility Clause bars member of Congress or civil officers of the U.S. from simultaneously serving in the military (especially the military reserves) has never been definitively resolved. A case involving the issue was litigated to the Supreme Court in Schlesinger v. Reservists Committee to Stop the War, but the Supreme Court decided the case on procedural grounds and did not address the Ineligibility Clause issue.[9] Congress has enacted legislation provided that "a Reserve of the armed forces who is not on active duty or who is on active duty for training is deemed not an employee or an individual holding an office of trust or profit or discharging an official function under or in connection with the U.S. because of his appointment, oath, or status, or any duties or functions performed or pay or allowances received in that capacity." A 2009 Congressional Research Service report noted that "Because Congress has the power to determine the qualifications of its own Members, the limitations that it has imposed on what constitutes an employee holding an office of the United States may be significant to courts considering the constitutional limitations."[9]

Creation and appointment

With the exception of military officers and certain court- and board-appointed officers, the method for creating an officer of the U.S. generally follows a set procedure. First, the Constitution must describe the office, or the U.S. Congress must create the office through a statute (though the president may independently create offices when exercising his exclusive jurisdiction in the exercise of foreign affairs, generally meaning ambassadorships). Second, the president nominates a person to fill the office and then commissions that person at which time the appointee comes to occupy the office and is an officer of the U.S. However, if the office is that of ambassador, "public minister" (member of the Cabinet of the U.S.), judge of the U.S. Supreme Court, or if the office has not been specifically vested for filling "in the President alone" by the authorizing legislation, then an intermediate step is required before the commission can be issued, namely, the U.S. Senate must give its "advise and consent" which, in practice, means approval by vote of a simple majority.[10]

An officer of the U.S. assumes his office's full authority upon the issuance of the commission. However, officers must take an oath of office before they can be paid.[11]

Statistics

According to a 2012 study by the Congressional Research Service, there are between 1,200 and 1,400 civilian officers of the U.S. which are subject to the "advice and consent" of the Senate prior to commissioning. A further 100,000 civilian officers of the U.S. have been exempted from this requirement by the U.S. Congress under the "inferior officer" exemption allowed by the Appointments Clause.[12]

Among military officers there were, as of 2012, 127,966 officers in the Selected Reserve and 365,483 officers in the U.S. Armed Forces. The NOAA Corps and U.S. Public Health Service had smaller numbers of officers.[13]

Examples

Officers of the U.S. in the executive branch are numerous, but some examples include the Secretary of Defense, the Attorney General, the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, the Director of National Intelligence, the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and members of the Federal Communications Commission and Interstate Commerce Commission.

Customs and courtesies

Commission certificate

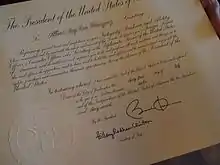

Most civilian officers of the U.S. are issued written commissions. Those who do not require confirmation of the Senate are provided semi-engraved commission certificates (partially printed with hand inscription of name, date, and title by a White House calligrapher) on letter-sized parchment. To this is set the signatures of the president and the U.S. Secretary of State applied by autopen. The document is sealed with the Great Seal of the U.S. Those who require confirmation of the Senate are issued fully engraved certificates (certificates completely hand-written by a calligrapher) on foolscap folio sized parchment. The President and Secretary of State usually hand-sign these certificates and, like others, they are sealed with the Great Seal.

The commissions of military officers are signed under the line "for the President" by the appropriate service secretary (e.g. the Secretary of the Army, Secretary of the Navy, Secretary of the Air Force, or for the Coast Guard, the Secretary of Homeland Security), instead of the Secretary of State, and are sealed with their respective departmental seal (e.g. Army seal) instead of the Great Seal.

The presentation of commissions for civilian officers generally follows the following style, or some variation thereof:

To all who shall see these presents, greeting: Know Ye that, reposing special trust in the integrity, ability, and fidelity of John Dow, I have nominated and, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, do appoint John Dow as Librarian of Congress, and do authorize and empower him to execute and fulfill the duties of that office according to law, and to have and to hold said office, with all the powers, privileges, and emoluments to the same of right appertaining unto him, the said Librarian of Congress, for the term of ten years, unless the President of the United States, for the time being, should be pleased sooner to revoke this commission. In testimony whereof, I have caused these letters to be made patent and the seal of the United States hereunto affixed.

Given under my hand, at the city of Washington, the twenty-ninth day of April, in the year of our Lord two thousand and sixteen, and of the independence of the United States of America the two-hundred and fortieth. BY THE PRESIDENT.

Honorific title

Civilian officers of the U.S. are permitted to be titled "the Honorable" for life, even after they cease being an officer of the U.S. In practice, however, this custom is rarely observed except in the case of judges. When it is invoked for non-judicial officers it is only done in written address or platform introductions and never by the official to whom it is applied in reference to him or herself.[14][15]

See also

References

- Plecnik, John (2014). "Officers Under the Appointments Clause". Pittsburgh Tax Review. 11 (2). doi:10.5195/TAXREVIEW.2014.26.

- Breger, Marshall (2015). Independent Agencies in the United States: Law, Structure, and Politics. Oxford University Press. pp. 160–166. ISBN 978-0199812127.

- Steven G. Bradbury (16 April 2007). Offices of the United States Within the Meaning of the Appointments Clause (PDF). United States Department of Justice Office of Legal Counsel.

- "Presidential Succession Act Law and Legal Definition". US Legal System. USLegal. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- Feerick, John. "Essays on Article II: Presidential Succession". The Heritage Guide to the Constitution. The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- Walter Dellinger (7 May 1996). The Constitutional Separation of Powers Between the President and Congress (PDF). United States Department of Justice Office of Legal Counsel. p. 144, n. 54.

- Campbell, Colton (2015). Congress and Civil-Military Relations. Georgetown University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-1626161801.

- Chandler, Robert (November 1941). "Public Officers: Can State or Municipal Officers Hold Office under the United States?". California Law Review. 30 (1): 99–101. doi:10.2307/3477237. JSTOR 3477237.

- Cynthia Brougher, Service by a Member of Congress in the U.S. Armed Forces Reserves, Congressional Research Service (June 10, 2009).

- England, Trent. "Commissions". heritage.org. The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- A Survivor's Guide for Presidential Nominees (PDF). National Academy of Public Administration. 2013. p. 41. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-13.

- Plumer, Brad (16 July 2013). "Does the Senate really need to confirm 1,200 executive branch jobs?". Washington Post. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- "2012 Demographics Profile of the Military Community" (PDF). militaryonesource.mil. U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- Mewborn, Mary (November 1999). "Too Many Honorables?". Washington Life. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- French, Mary Mel (2010). United States Protocol. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 167.