Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigate

The Oliver Hazard Perry class is a class of guided-missile frigates named after U.S. Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, the hero of the naval Battle of Lake Erie. Also known as the Perry or FFG-7 (commonly "fig seven") class, the warships were designed in the United States in the mid-1970s as general-purpose escort vessels inexpensive enough to be bought in large numbers to replace World War II-era destroyers and complement 1960s-era Knox-class frigates.[1]

The frigates Oliver Hazard Perry, Antrim, and Jack Williams in 1982 | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Oliver Hazard Perry class |

| Builders |

|

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Brooke class |

| Succeeded by | Constellation class |

| Subclasses |

|

| Cost | US$122 million |

| Built | 1975–2004 |

| In commission | 1977–present |

| Planned | 71 |

| Completed | 71 |

| Active |

|

| Laid up | 8 |

| Retired | 45 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Guided-missile frigate |

| Displacement | 4,100 long tons (4,200 t) full load |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 45 ft (14 m) |

| Draft | 22 ft (6.7 m) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph) |

| Range | 4,500 nmi (8,300 km; 5,200 mi) at 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) |

| Complement | 176 |

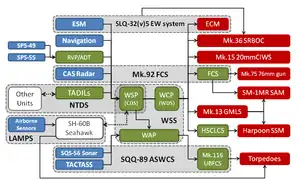

| Sensors and processing systems |

|

| Electronic warfare & decoys |

|

| Armament |

|

| Aircraft carried | 2 × LAMPS multi-purpose helicopters (the SH-2 Seasprite LAMPS I on the short-hulled ships or the SH-60 Seahawk LAMPS III on the long-hulled ships) |

In Admiral Elmo Zumwalt's "high low fleet plan", the FFG-7s were the low-capability ships, with the Spruance-class destroyers serving as the high-capability ships. Intended to protect amphibious landing forces, supply and replenishment groups, and merchant convoys from aircraft and submarines, they were also later part of battleship-centered surface action groups and aircraft carrier battle groups/strike groups.[1] 55 ships were built in the United States: 51 for the United States Navy and four for the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). Eight were built in Taiwan, six in Spain, and two in Australia for their navies. Former U.S. Navy warships of this class have been sold or donated to the navies of Bahrain, Egypt, Poland, Pakistan, Taiwan, and Turkey.

The first of the 51 U.S. Navy-built Oliver Hazard Perry frigates entered into service in 1977, and the last remaining in active service, USS Simpson, was decommissioned on 29 September 2015.[2] The retired vessels were mostly mothballed with some transferred to other navies for continued service and some used as weapons targets and sunk. Some of the U.S. Navy's frigates, such as USS Duncan (14.6 years in service), had fairly short careers, while a few lasted as long as 30+ years in active U.S. service, with some lasting even longer after being sold or donated to other navies.[3][4] In 2020, the Navy announced the new Constellation class as their latest class of frigates.

Design and construction

_outboard_profile.jpg.webp)

The ships were designed by the Bath Iron Works shipyard in Maine in partnership with the New York-based naval architects Gibbs & Cox. The design process was notable as the initial design was accomplished with the help of computers in 18 hours by Raye Montague, a civilian U.S. Navy naval engineer, making it the first ship designed by computer.[5]

The Oliver Hazard Perry-class ships were produced in 445-foot (136 m) long "short-hull" (Flight I) and 453-foot (138 m) long "long-hull" (Flight III) variants. The long-hull ships (FFG 8, 28, 29, 32, 33, and 36–61) carry the larger SH-60 Seahawk LAMPS III helicopters, while the short-hulled warships carry the smaller and less-capable SH-2 Seasprite LAMPS I. Aside from the lengths of their hulls, the principal difference between the versions is the location of the aft capstan: on long-hull ships, it sits a step below the level of the flight deck to provide clearance for the tail rotor of the longer Seahawk helicopters.[6]

The long-hull ships carry the RAST (Recovery Assist Securing and Traversing) system (also known as a Beartrap (hauldown device)) for the Seahawk. It is a hook, cable, and winch system that can reel in a Seahawk from a hovering flight, expanding the ship's pitch-and-roll range in which flight operations are permitted. The FFG 8, 29, 32, and 33 were built as "short-hull" warships but were later modified into "long-hull" warships.[6]

Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates were the second class of surface ships (after the Spruance-class destroyers) in the U.S. Navy to be built with gas turbine propulsion. The gas turbine propulsion plant was more automated than other Navy propulsion plants at the time, and it could be centrally monitored and controlled from a remote engineering control center away from the engines. The gas turbine propulsion plants also allowed the ship's speed to be controlled directly from the bridge via a throttle control, a first for the U.S. Navy.

American shipyards constructed Oliver Hazard Perry-class ships for the U.S. Navy and the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). Early American-built Australian ships were originally built as the "short-hull" version, but they were modified during the 1980s to the "long-hull" design. Shipyards in Australia, Spain, and Taiwan have produced several warships of the "long-hull" design for their navies.

Although the per-ship costs rose greatly over the period of production,[7] all 51 ships planned for the U.S. Navy were built.

During the design phase of the Oliver Hazard Perry class, the head of the Royal Corps of Naval Constructors, R.J. Daniels, was invited by an old friend, U.S. Chief of the Bureau of Ships, Adm Robert C Gooding, to advise upon the use of variable-pitch propellers in the class. During this conversation, Daniels warned Gooding against the use of aluminium in the superstructure of the FFG-7 class as he believed it would lead to structural weaknesses. A number of ships subsequently developed structural cracks, including a 40 ft (12 m) fissure in USS Duncan, before the problems were remedied.[8]

The Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates were designed primarily as anti-aircraft and anti-submarine warfare guided-missile warships intended to provide open-ocean escort of amphibious warfare ships and merchant ship convoys in moderate threat environments in a potential war with the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact countries. They could also provide air defense against 1970s- and 1980s-era aircraft and anti-ship missiles. These warships are equipped to escort and protect aircraft carrier battle groups, amphibious landing groups, underway replenishment groups, and merchant ship convoys. They can conduct independent operations to perform tasks such as surveillance of illegal drug smugglers, maritime interception operations, and exercises with other nations.[9]

The addition of the Naval Tactical Data System, LAMPS helicopters, and the Tactical Towed Array System (TACTAS) gave these warships a combat capability far beyond the original expectations. They are well suited for operations in littoral regions and most war-at-sea scenarios.

Notable combat actions

Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates made worldwide news during the 1980s. Despite being small, these frigates were shown to be very durable. During the Iran–Iraq War, on 17 May 1987, USS Stark was attacked by an Iraqi warplane. Struck by two Exocet anti-ship missiles, thirty-seven U.S. Navy sailors died in the deadly prelude to the American Operation Earnest Will, the reflagging and escorting of oil tankers through the Persian Gulf and the Straits of Hormuz.

Less than a year later, on 14 April 1988, USS Samuel B. Roberts was nearly sunk by an Iranian mine. There were no deaths, but ten sailors were evacuated from the warship for medical treatment. The crew of Samuel B. Roberts battled fire and flooding for two days, ultimately managing to save the ship. The U.S. Navy retaliated four days later with Operation Praying Mantis, a one-day attack on Iranian oil platforms being used as bases for raids on merchant shipping. Those had included bases for the minelaying operations that damaged Samuel B. Roberts. Stark and Roberts were each repaired in American shipyards and returned to full service. Stark was decommissioned in 1999 and scrapped in 2006. Roberts was decommissioned at Mayport on 22 May 2015.[10]

On 18 April 1988, USS Simpson was accompanying the cruiser USS Wainwright and frigate USS Bagley when they came under attack from the Iranian gunboat Joshan, which fired a U.S.-made Harpoon anti-ship missile at the ships. With Simpson having the only clear shot, the frigate fired an SM-1 standard missile, which struck Joshan. Simpson fired three more SM-1s, and with later naval fire from Wainwright, sank the Iranian vessel.[11]

Durability

On 14 July 2016, the ex-USS Thach took over 12 hours to sink after being used in a live fire, SINKEX during naval exercise RIMPAC 2016. During the exercise, the ship was directly or indirectly hit with the following ordnance: a Harpoon missile from a South Korean submarine, another Harpoon missile from the Australian frigate HMAS Ballarat, a Hellfire missile from an Australian MH-60R helicopter, another Harpoon missile and a Maverick missile from U.S. maritime patrol aircraft, another Harpoon missile from the cruiser USS Princeton, additional Hellfire missiles from a U.S. Navy MH-60S helicopter, a 900 kg (2,000 lb) Mark 84 bomb from a U.S. Navy F/A-18 Hornet, a GBU-12 Paveway laser-guided 225 kg (500 lb) bomb from a U.S. Air Force B-52 bomber, and a Mark 48 torpedo from an unnamed U.S. Navy submarine.[12][13]

Modifications

United States

The United States Navy and Royal Australian Navy modified their remaining Perrys to reduce their operating costs, replacing Detroit Diesel 16V149TI electrical generators with Caterpillar 3512B diesel engines.

Upgrades to the Perry class were problematic due to "little reserved space for growth (39 tons in the original design), and the inflexible, proprietary electronics of the time", such that the "US Navy gave up on the idea of upgrades to face new communications realities and advanced missile threats". The U.S. Navy decommissioned 25 "FFG-7 Short" ships via "bargain basement sales to allies or outright retirement, after an average of only 18 years of service".[6]

From 2004 to 2005, the U.S. Navy removed the frigates' Mk 13 single-arm missile launchers because the primary missile, the Standard SM-1MR, had become outmoded. It would supposedly have been too costly to refit the Standard SM-1MR missiles, which had little ability to bring down sea-skimming missiles. Another reason was to allow more SM-1MRs to go to American allies that operated Perrys, such as Poland, Spain, Australia, Turkey, and Taiwan.[14] As a result, the "zone-defense" anti-aircraft warfare (AAW) capability of the U.S. Navy's Perrys had vanished, and all that remained was a "point-defense" type of anti-air warfare armament, so they relied upon cover from AEGIS destroyers and cruisers.[6]

.jpg.webp)

The removal of the Mk 13 launchers also stripped the frigates of their Harpoon anti-ship missiles. However, their Seahawk helicopters could still carry the much shorter-range Penguin and Hellfire anti-ship missiles. The last nine ships of the class had new remotely operated 25 mm Mk 38 Mod 2 Machine Gun Systems (MGSs) installed on platforms over the old Mk 13 launcher magazine.

_departs_Joint_Base_Pearl_Harbor-Hickam_to_support_Rim_of_the_Pacific_(RIMPAC)_2010_exercises.jpg.webp)

._Behind_the_barrel_is_the_Separate_Target_Illuminatio_-_DPLA_-_936cbf1336b76f7fc0b4727a4bb05e99.jpg.webp)

Up to 2002, the U.S. Navy updated the remaining active Oliver Hazard Perry-class warships' Phalanx CIWS to the "Block 1B" capability, which allowed the Mk 15 20 mm Phalanx gun to shoot at fast-moving surface craft and helicopters. They were also to have been fitted with the Mk 53 Decoy Launching System "Nulka" in place of the SRBOC (Super Rapid Blooming Offboard Chaff) and flares, which would have better protected the ship against anti-ship missiles. It was planned to outfit the remaining ships with a 21-cell RIM-116 Rolling Airframe Missile launcher at the location of the former Mk 13, but this did not occur.[15]

On 11 May 2009, the first International Frigate Working Group met at Mayport Naval Station to discuss maintenance, obsolescence, and logistics issues regarding Oliver Hazard Perry-class ships of the U.S. and foreign navies.[16]

On 16 June 2009, Vice Admiral Barry McCullough turned down the suggestion of then-U.S. Senator Mel Martinez (R-FL) to keep the Perrys in service, citing their worn-out and maxed-out condition.[17] However, U.S. Representative Ander Crenshaw (R-FL) and former U.S. Representative Gene Taylor (D-MS) took up the cause to retain the vessels.[18]

The Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates were to have been eventually replaced by Littoral Combat Ships by 2019. However, the worn-out frigates were being retired faster than the LCSs were being built, which may lead to a gap in United States Southern Command mission coverage.[19] According to Navy deactivation plans, all Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates would be retired by October 2015. Simpson was the last to be retired (on 29 September 2015), leaving the Navy devoid of frigates for the first time since 1943. The ships will either be made available for sale to foreign navies or dismantled.[20]

Perry-class frigate retirement was accelerated by budget pressures, leading to the remaining 11 ships being replaced by only eight LCS hulls. With the timeline LCS mission packages will come online unknown, there is uncertainty if they will be able to perform the frigates' counter-narcotics and anti-submarine roles when they are gone. The Navy is looking into Military Sealift Command to see if the Joint High Speed Vessel, Mobile Landing Platform, and other auxiliary ships could handle low-end missions that the frigates performed.[21]

The U.S. Coast Guard harvested weapons systems components from decommissioned Navy Perry-class frigates to save money. Harvesting components from four decommissioned frigates resulted in more than $24 million in cost savings, which increases with parts from more decommissioned frigates. Equipment including Mk 75 76 mm/62 caliber gun mounts, gun control panels, barrels, launchers, junction boxes, and other components was returned to service aboard Famous-class cutters to extend their service lives into the 2030s.[22]

In June 2017, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson revealed the Navy was "taking a hard look" at reactivating 7-8 out of 12 mothballed Perry-class frigates to increase fleet numbers. While the move was under consideration, there would be difficulties in returning them to service given the age of the ships and their equipment, likely requiring a significant modernization effort. Although bringing the frigates out of retirement would have provided a short-term solution to fleet size, their limited combat capability would restrict them to acting as a theater security cooperation, maritime security asset.[23][24] Their likely role would have been serving as basic surface platforms that stay close to U.S. shores, performing missions such as assisting drug interdiction efforts or patrolling the Arctic so an extensive upgrade to the ships' combat systems would not need to be undertaken.[25] An October 2017 memo recommended against reactivating the frigates, claiming it would cost too much money, taking funding away from other Navy priorities for ships with little effectiveness.[26]

Australia

_underway_in_the_Philipine_Sea_on_18_April_2019_(190418-N-UI104-0759).JPG.webp)

Australia spent A$1.46bn to upgrade the Royal Australian Navy's (RAN) Adelaide-class guided-missile frigates, including equipping them to fire the SM-2 version of the Standard missile, adding an eight-cell Mark 41 Vertical Launching System (VLS) for Evolved SeaSparrow Missiles (ESSMs), and installing better air-search radars and long-range sonar. The RAN had opted to retain their Adelaide frigates rather than purchase the U.S. Navy's Kidd-class destroyers; the Kidds were more capable but more expensive and manpower intensive. However, the upgrade project ran over budget and fell behind schedule.[6]

The first of the upgraded frigates, HMAS Sydney, returned to the RAN fleet in 2005. Four frigates were eventually upgraded at the Garden Island shipyard in Sydney, Australia, with the modernizations lasting between 18 months and two years. The cost of the upgrades was partly offset, in the short run, by the decommissioning and disposal of the two older frigates. HMAS Canberra was decommissioned on 12 November 2005 at naval base HMAS Stirling in Western Australia, and HMAS Adelaide was decommissioned at that same naval base on 20 January 2008. HMAS Sydney was decommissioned at the Garden Island naval base in 2016. HMAS Darwin was also decommissioned at Garden Island in 2018.

The Adelaide-class frigates were replaced by three Hobart-class air warfare destroyers equipped with the AEGIS combat system. HMAS Melbourne and Newcastle were transferred in May 2020 to the Chilean Navy and serve as Captain Prat and Almirante Latorre.

Turkey

The Turkish Navy started the modernization of its G-class frigates with the GENESIS (Gemi Entegre Savaş İdare Sistemi) combat management system in 2007.[27] The first GENESIS upgraded ship was delivered in 2007, and the last delivery was scheduled for 2011.[28] The "short-hull" Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates that are currently part of the Turkish Navy were modified with the ASIST landing platform system at the Gölcük Naval Shipyard so that they can accommodate the S-70B Seahawk helicopters. Turkey is planning to add one eight-cell Mk 41 VLS for the ESSM, to be installed forward of the present Mk 13 missile launchers, similar to the case in the modernization program of the Australian Adelaide-class frigates.[29][30][31]

TCG Gediz was the first ship in the class to receive the Mk 41 VLS installation.[32] There are plans for new components to be installed that are being developed for the Milgem-class warships (Ada-class corvettes and F-100-class frigates) of the Turkish Navy. These include modern Three-dimensional and X-band radars developed by ASELSAN and Turkish-made hull-mounted sonars. One of the G-class frigates will also be used as a test-bed for Turkey's 6,000+ ton TF2000-class AAW frigates that are currently being designed by the Turkish Naval Institute.

Operators

Bahrain: USS Jack Williams was purchased from the American government in 1996 and re-christened Sabha.

Bahrain: USS Jack Williams was purchased from the American government in 1996 and re-christened Sabha. Chile: On 27 December 2019, it was announced that Australia had sold HMAS Newcastle and HMAS Melbourne to Chile. Both frigates were delivered to the Chilean Navy in May 2020 and named Capitan Prat and Almirante Latorre.[33]

Chile: On 27 December 2019, it was announced that Australia had sold HMAS Newcastle and HMAS Melbourne to Chile. Both frigates were delivered to the Chilean Navy in May 2020 and named Capitan Prat and Almirante Latorre.[33] Egypt: Four Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates were transferred from the U.S. Navy between 1996 and 1999.[34]

Egypt: Four Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates were transferred from the U.S. Navy between 1996 and 1999.[34] Pakistan: The former USS McInerney transferred to the Pakistani Navy as PNS Alamgir (F260) in August 2010.[35]

Pakistan: The former USS McInerney transferred to the Pakistani Navy as PNS Alamgir (F260) in August 2010.[35] Poland: Two frigates were transferred from the U.S. Navy in 2000 and 2002.

Poland: Two frigates were transferred from the U.S. Navy in 2000 and 2002. Spain (Santa María class): Spanish-built: six frigates.

Spain (Santa María class): Spanish-built: six frigates. Taiwan (Cheng Kung class): Taiwanese-built. Originally, eight ships were equipped with eight Hsiung Feng II anti-ship missiles. Now, all but PFG-1103 are carrying four HF-2 and four HF-3 supersonic AShM. The PFG-1103 Cheng Ho will change the anti-ship mix upon their major overhaul. Seven out of eight ships added Bofors 40 mm/L70 guns for both surface and anti-air use. On 5 November 2012, Minister of Defense Kao announced the U.S. government would sell Taiwan two additional Perry-class frigates that are about to be retired from the U.S. Navy for a cost of US$240 million to be retrofitted and delivered in 2015.[36] The ex-USS Gary and the ex-USS Taylor were to be reactivated and transferred to Taiwan. In July 2016, the U.S. Naval Sea Systems Command awarded a $74 million contract to Virginia-based VSE Corporation to do the work. According to the contract, VSE had 16 months to complete the work. The U.S. State Department officially approved the sale of both ships for $190 million in March 2016.[37] The ships were commissioned into ROCN service on 8 November 2018.[38]

Taiwan (Cheng Kung class): Taiwanese-built. Originally, eight ships were equipped with eight Hsiung Feng II anti-ship missiles. Now, all but PFG-1103 are carrying four HF-2 and four HF-3 supersonic AShM. The PFG-1103 Cheng Ho will change the anti-ship mix upon their major overhaul. Seven out of eight ships added Bofors 40 mm/L70 guns for both surface and anti-air use. On 5 November 2012, Minister of Defense Kao announced the U.S. government would sell Taiwan two additional Perry-class frigates that are about to be retired from the U.S. Navy for a cost of US$240 million to be retrofitted and delivered in 2015.[36] The ex-USS Gary and the ex-USS Taylor were to be reactivated and transferred to Taiwan. In July 2016, the U.S. Naval Sea Systems Command awarded a $74 million contract to Virginia-based VSE Corporation to do the work. According to the contract, VSE had 16 months to complete the work. The U.S. State Department officially approved the sale of both ships for $190 million in March 2016.[37] The ships were commissioned into ROCN service on 8 November 2018.[38] Turkey (G class): Eight former U.S. Navy Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates were transferred to the Turkish Navy between 1998 and 2003.[39] All have undergone extensive advanced modernization programs, and they are now known as the G-class frigates. The Turkish Navy modernized G-class frigates have an additional Mk 41 VLS capable of launching ESSMs for closer-in defense and longer-range SM-1 missiles, advanced digital fire control systems, and new Turkish-made sonars.

Turkey (G class): Eight former U.S. Navy Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates were transferred to the Turkish Navy between 1998 and 2003.[39] All have undergone extensive advanced modernization programs, and they are now known as the G-class frigates. The Turkish Navy modernized G-class frigates have an additional Mk 41 VLS capable of launching ESSMs for closer-in defense and longer-range SM-1 missiles, advanced digital fire control systems, and new Turkish-made sonars.

Potential operators

Mexico: Two former U.S. Navy Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates USS McClusky and USS Curts were to be sold to the Mexican Navy under the FMS, however USS McClusky was sunk as a target during RIMPAC 2018 on 19 July 2018[40] and USS Curts was sunk as a target during Valiant Shield 2020 on 19 September 2020.[41]

Mexico: Two former U.S. Navy Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates USS McClusky and USS Curts were to be sold to the Mexican Navy under the FMS, however USS McClusky was sunk as a target during RIMPAC 2018 on 19 July 2018[40] and USS Curts was sunk as a target during Valiant Shield 2020 on 19 September 2020.[41] Thailand: Two former U.S. Navy Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates were allocated by the U.S. government to the Royal Thai Navy, subject to acceptance by the Thai government: the former USS Rentz and USS Vandegrift.[42] This transfer was not carried out; Rentz was sunk as a target during Exercise Valiant Shield 2016,[43] and Vandegrift was sunk as a target during Exercise Valiant Shield 2022.[44]

Thailand: Two former U.S. Navy Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates were allocated by the U.S. government to the Royal Thai Navy, subject to acceptance by the Thai government: the former USS Rentz and USS Vandegrift.[42] This transfer was not carried out; Rentz was sunk as a target during Exercise Valiant Shield 2016,[43] and Vandegrift was sunk as a target during Exercise Valiant Shield 2022.[44] Ukraine: Two former U.S. Navy Oliver Hazard Perry-class ships were offered to the Ukrainian Navy in 2018 to increase its operational capacity in the Azov and Black seas after it was significantly reduced following the annexation of Crimea by Russia (a large part of Ukrainian navy vessels stationed there were seized).[45][46]

Ukraine: Two former U.S. Navy Oliver Hazard Perry-class ships were offered to the Ukrainian Navy in 2018 to increase its operational capacity in the Azov and Black seas after it was significantly reduced following the annexation of Crimea by Russia (a large part of Ukrainian navy vessels stationed there were seized).[45][46]

Former operators

.svg.png.webp) Australia (Adelaide class): The Royal Australian Navy purchased six frigates. Four of them were built in the United States, while the other two were built in Australia. Four of the ships were upgraded with the addition of an eight-cell Mk 41 VLS with 32 ESSMs, and the Standard Missile SM-2, plus upgraded radars and sonars, while the other two ships were decommissioned at that time. They have been replaced by the Hobart-class air-warfare destroyers, with the last Adelaide-class frigate HMAS Melbourne retiring on 26 October 2019.

Australia (Adelaide class): The Royal Australian Navy purchased six frigates. Four of them were built in the United States, while the other two were built in Australia. Four of the ships were upgraded with the addition of an eight-cell Mk 41 VLS with 32 ESSMs, and the Standard Missile SM-2, plus upgraded radars and sonars, while the other two ships were decommissioned at that time. They have been replaced by the Hobart-class air-warfare destroyers, with the last Adelaide-class frigate HMAS Melbourne retiring on 26 October 2019..svg.png.webp) United States: The U.S. Navy commissioned 51 FFG-7 class frigates between 1977 and 1989. The last of these, Simpson, was decommissioned on 29 September 2015.[47]

United States: The U.S. Navy commissioned 51 FFG-7 class frigates between 1977 and 1989. The last of these, Simpson, was decommissioned on 29 September 2015.[47]

List of vessels

| Ship name | Hull no. | Hull length | Builder | Commission– decommission |

Fate | Link | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S.-built | |||||||

| Oliver Hazard Perry | FFG-7 | Short | Bath Iron Works | 1977–1997 | Disposed of by scrapping, dismantling, 21 April 2006 | ||

| McInerney | FFG-8 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1979–2010 | Transferred to Pakistan Navy as PNS Alamgir (F260), 31 August 2010[48] | ||

| Wadsworth | FFG-9 | Short | Todd Pacific Shipyards, Los Angeles Division, (Todd, San Pedro) | 1980–2002 | Transferred to Polish Navy as ORP Gen. T. Kościuszko (273), 28 June 2002[49] | ||

| Duncan | FFG-10 | Short | Todd Pacific Shipyards, Seattle Division | 1980–1994 | Transferred to Turkish Naval Forces as a parts hulk, 5 April 1999. Scuttled October 2017[50][51] | ||

| Clark | FFG-11 | Short | Bath Iron Works | 1980–2000 | Transferred to Polish Navy as ORP Gen. K. Pułaski (272), 15 March 2000 | ||

| George Philip | FFG-12 | Short | Todd, San Pedro | 1980–2003 | Disposed of by scrapping, dismantling, 23 January 2017[52][53] | ||

| Samuel Eliot Morison | FFG-13 | Short | Bath Iron Works | 1980–2002 | Transferred to Turkish Naval Forces as TCG Gokova (F 496), 10 April 2002[54] | ||

| Sides | FFG-14 | Short | Todd, San Pedro | 1981–2003 | Disposed of by scrapping, dismantling, 25 January 2016[53] | ||

| Estocin | FFG-15 | Short | Bath Iron Works | 1981–2003 | Transferred to Turkish Naval Forces as TCG Goksu (F497), 3 April 2003[55] | ||

| Clifton Sprague | FFG-16 | Short | Bath Iron Works | 1981–1995 | Transferred to Turkish Naval Forces as TCG Gaziantep (F490), 27 August 1997 | ||

| built for Royal Australian Navy as HMAS Adelaide | FFG-17 | Short | Todd, Seattle | 1980–2008 | Disposed, sunk as diving & fishing reef, 13 April 2011[56] | ||

| built for Royal Australian Navy as HMAS Canberra | FFG-18 | Short | Todd, Seattle | 1981–2005 | Disposed, sunk as diving & fishing reef, 4 October 2009[57] | ||

| John A. Moore | FFG-19 | Short | Todd, San Pedro | 1981–2000 | Transferred to Turkish Naval Forces as TCG Gediz (F495), 1 September 2000 | ||

| Antrim | FFG-20 | Short | Todd, Seattle | 1981–1996 | Transferred to Turkish Naval Forces as TCG Giresun (F491), 27 August 1997 | ||

| Flatley | FFG-21 | Short | Bath Iron Works | 1981–1996 | Transferred to Turkish Naval Forces as TCG Gemlik (F492), 10 October 2001 | ||

| Fahrion | FFG-22 | Short | Todd, Seattle | 1982–1998 | Transferred to Egyptian Navy as Sharm El-Sheik (F901), 15 March 1998 | ||

| Lewis B. Puller | FFG-23 | Short | Todd, San Pedro | 1982–1998 | Transferred to Egyptian Navy as Toushka (F906), 18 September 1998 | ||

| Jack Williams | FFG-24 | Short | Bath Iron Works | 1981–1996 | Transferred to Royal Bahrain Naval Force as RBNS Sabha (FFG-90), 13 September 1996 | ||

| Copeland | FFG-25 | Short | Todd, San Pedro | 1982–1996 | Transferred to Egyptian Navy as Mubarak (F911), 18 September 1996, renamed Alexandria in 2011 | ||

| Gallery | FFG-26 | Short | Bath Iron Works | 1981–1996 | Transferred to Egyptian Navy as Taba (F916), 25 September 1996 | ||

| Mahlon S. Tisdale | FFG-27 | Short | Todd, San Pedro | 1982–1996 | Transferred to Turkish Naval Forces as TCG Gokceada (F494), 5 April 1999 | ||

| Boone | FFG-28 | Long | Todd, Seattle | 1982–2012 | Disposed, sunk as target, 7 September 2022[58] | ||

| Stephen W. Groves | FFG-29 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1982–2012 | Decommissioned, to be disposed of by scrapping, dismantling, 24 February 2012[59][60] | ||

| Reid | FFG-30 | Short | Todd, San Pedro | 1983–1998 | Transferred to Turkish Naval Forces as TCG Gelibolu (F 493), 5 January 1999 | ||

| Stark | FFG-31 | Short | Todd, Seattle | 1982–1999 | Disposed of by scrapping, dismantling, 21 June 2006 | ||

| John L. Hall | FFG-32 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1982–2012 | Decommissioned, to be disposed of by scrapping, dismantling, 9 March 2012[59][61] | ||

| Jarrett | FFG-33 | Long | Todd, San Pedro | 1983–2011 | Disposed of by scrapping, dismantling, 1 August 2016[53] | ||

| Aubrey Fitch | FFG-34 | Short | Bath Iron Works | 1982–1997 | Disposed of by scrapping, dismantling, 19 May 2005 | ||

| built for Royal Australian Navy as HMAS Sydney | FFG-35 | Long | Todd, Seattle | 1983–2015 | Scrapped 2017[62][63][64] | ||

| Underwood | FFG-36 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1983–2013 | Decommissioned, to be disposed of by scrapping, dismantling, 8 March 2013[59][65] | ||

| Crommelin | FFG-37 | Long | Todd, Seattle | 1983–2012 | Disposed of as target during RIMPAC 2016 SINKEX, 19 July 2016[66] | ||

| Curts | FFG-38 | Long | Todd, San Pedro | 1983–2013 | Disposed of as target during Valiant Shield 2020 SINKEX, 19 September 2020[67] | ||

| Doyle | FFG-39 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1983–2011 | Disposed of by scrapping, dismantling, 12 June 2019[59][68] | ||

| Halyburton | FFG-40 | Long | Todd, Seattle | 1984–2014 | Decommissioned, on hold for donation[69] | ||

| McClusky | FFG-41 | Long | Todd, San Pedro | 1983–2015 | Disposed of as target during RIMPAC 2018 SINKEX, 19 July 2018[70] | ||

| Klakring | FFG-42 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1983–2013 | Decommissioned, on hold for foreign military sale, 22 March 2013[59][71] | ||

| Thach | FFG-43 | Long | Todd, San Pedro | 1984–2013 | Disposed of as target during RIMPAC 2016 SINKEX, 14 July 2016[72] | ||

| built for Royal Australian Navy as HMAS Darwin | FFG-44 | Long | Todd, Seattle | 1984–2017 | Decommissioned 9 December 2017 | ||

| De Wert | FFG-45 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1983–2014 | Decommissioned, on hold for foreign military sale, 4 April 2014[59][73] | ||

| Rentz | FFG-46 | Long | Todd, San Pedro | 1984–2014 | Disposed of as target during Valiant Shield 2016 SINKEX, 13 September 2016[74] | ||

| Nicholas | FFG-47 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1984–2014 | Decommissioned, to be disposed of by scrapping, dismantling, 10 March 2014[59][75] | ||

| Vandegrift | FFG-48 | Long | Todd, Seattle | 1984–2015 | Disposed of as target during Valiant Shield 2022 SINKEX, 17 June 2022[76] | ||

| Robert G. Bradley | FFG-49 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1984–2014 | Decommissioned on 28 March 2014,[59][77][78] to be transferred to Royal Bahrain Naval Force in late 2019. | ||

| Taylor | FFG-50 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1984–2015 | Transferred to Taiwan as ROCS Ming-chuan (PFG-1112), 9 March 2016[79] | ||

| Gary | FFG-51 | Long | Todd, San Pedro | 1984–2015 | Transferred to Taiwan as ROCS Feng Jia (PFG-1115), 9 March 2016[80][81] | ||

| Carr | FFG-52 | Long | Todd, Seattle | 1985–2013 | Decommissioned, on hold for foreign military sale, 13 March 2013[59][82][83] | ||

| Hawes | FFG-53 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1985–2010 | Decommissioned, to be disposed of by scrapping, dismantling, 10 December 2010[59] | ||

| Ford | FFG-54 | Long | Todd, San Pedro | 1985–2013 | Disposed of as target during Pacific Griffin 2019 SINKEX, 1 October 2019[84] | ||

| Elrod | FFG-55 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1985–2015 | Decommissioned, on hold for foreign military sale, 30 January 2015[59][85] | ||

| Simpson | FFG-56 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1985–2015 | Decommissioned, on hold for foreign military sale, 29 September 2015[59][86][87] | ||

| Reuben James | FFG-57 | Long | Todd, San Pedro | 1986–2013 | Disposed of as target during live fire missile test, 19 January 2016[88] | ||

| Samuel B. Roberts | FFG-58 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1986–2015 | Decommissioned, to be disposed of by scrapping, dismantling, 22 May 2015[59][89] | ||

| Kauffman | FFG-59 | Long | Bath Iron Works | 1987–2015 | Decommissioned, on hold for foreign military sale, 18 September 2015[59][90][91] | ||

| Rodney M. Davis | FFG-60 | Long | Todd, San Pedro | 1987–2015 | Disposed of as target during RIMPAC 2022 SINKEX, 12 July 2022[92] | ||

| Ingraham | FFG-61 | Long | Todd, San Pedro | 1989–2014 | Disposed of as target during LSE 21 SINKEX, 15 August 2021[93] | ||

| Ship Name | Hull No. | Builder | Commission– Decommission |

Fate | Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australian-built | |||||

| HMAS Melbourne | FFG 05 | Australian Marine Engineering Consolidated (AMECON), Williamstown, Victoria | 1992–2019 | Decommissioned. Sold to Chile in 2020 | |

| HMAS Newcastle | FFG 06 | 1993–2019 | Decommissioned. Sold to Chile in 2020 | ||

| Spanish-built | |||||

| Santa María | F81 | Bazan, Ferrol | 1986– | In active service | |

| Victoria | F82 | 1987– | In active service | ||

| Numancia | F83 | 1989– | In active service | ||

| Reina Sofía | F84 | 1990– | In active service | ||

| Navarra | F85 | 1994– | In active service | ||

| Canarias | F86 | 1994– | In active service | ||

| Taiwan-built (Republic of China) | |||||

| ROCS Cheng Kung | PFG-1101 | China Shipbuilding, Kaohsiung, Taiwan | 1993– | In active service | |

| ROCS Cheng Ho | PFG-1103 | 1994– | In active service | ||

| ROCS Chi Kuang | PFG-1105 | 1995– | In active service | ||

| ROCS Yueh Fei | PFG-1106 | 1996– | In active service | ||

| ROCS Tzu I | PFG-1107 | 1997– | In active service | ||

| ROCS Pan Chao | PFG-1108 | 1997– | In active service | ||

| ROCS Chang Chien | PFG-1109 | 1998– | In active service | ||

| ROCS Tian Dan | PFG-1110 | 2004– | In active service | ||

Related legislation

The Naval Vessel Transfer Act of 2013[94] authorized the transfer of Curts and McClusky to Mexico, and the sale of Taylor, Gary, Carr, and Elrod to the Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office in the United States (which is the Taiwan agency designated under the Taiwan Relations Act) for about $10 million each.[95]

Considered for reactivation

On 13 June 2017, the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral John M. Richardson announced that U.S. Navy officials were looking into the possibility of recommissioning several Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates from its inactive fleet to help build up and support President Donald Trump's proposed 355-ship navy plan.[96] On 11 December 2017, the Navy decided against reactivating the class, citing that reactivating the ships would prove too costly.[97]

As of 8 September 2022, the remaining Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates, kept at the Naval Inactive Ship Maintenance Facility in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, are:

- USS Robert G. Bradley (FFG-49)

- USS Carr (FFG-52)

- USS De Wert (FFG-45)

- USS Elrod (FFG-55)

- USS Stephen W. Groves (FFG-29)

- USS John L. Hall (FFG-32)

- USS Halyburton (FFG-40)

- USS Hawes (FFG-53)

- USS Kauffman (FFG-59)

- USS Klakring (FFG-42)

- USS Nicholas (FFG-47)

- USS Samuel B. Roberts (FFG-58)

- USS Simpson (FFG-56)

- USS Underwood (FFG-36)

References

- Wiggins, James F (August 2000). Defense Acquisitions: Comprehensive Strategy Needed to Improve Ship Cruise Missile Defence. United States General Accounting Office. ISBN 978-0-7567-0302-8. Retrieved 16 February 2010. pp.42

- "US Navy decommissions last Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigate USS Simpson". Baval-technology.com. 30 September 2015. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- Vergakis, Brock (7 January 2015). "Last deployment: All Navy frigates soon to be decommissioned". Associated Press. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- Rogoway, Tyler (10 January 2014). "End Of The 'Ghetto Navy' Is In Sight As Last USN Frigate Cruise Begins". Fox Trot Alpha. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- "Raye Jean Jordan Montague (1935–2018) - Encyclopedia of Arkansas". Encyclopediaofarkansas.net. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "Australias Hazard(ous) Frigate Upgrades: Done at Last".

- "FFG-7 OLIVER HAZARD PERRY class". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- Daniels, R.J, p.219, The End of an Era: The Memoirs of a Naval Constructor, Periscope Publishing Ltd, 2004, ISBN 1-904381-18-9, ISBN 978-1-904381-18-1

- Raleigh Clayton Muns, Oliver Hazard Perry Class Frigates: United States Navy (2010), p.3

- Peniston, Bradley (23 May 2015). "The Once—and Future?—USS Samuel B. Roberts". Defense One. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- Lendon, Brad (29 September 2015). "Hours before decommissioning, USS Simpson crew recall historic naval battle". Cnn.com. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- "Former Frigate USS Thach Hit in Live Fire Sinking Exercise". USNI News. USNI News. 18 July 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- "Watch the Navy Send a Retired Frigate Out With a Bang". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- Burgess, Richard R. (September 2003). "Guided Missiles Removed from Perry-class Frigates (Sea Services section: Northrop Grumman-Built DDG Mustin Commissioned in U.S. Pacific Fleet)". Sea Power. Washington, D.C.: Navy League of the United States. 46 (9): 34. ISSN 0199-1337. OCLC 3324011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- The Naval Institute Guide to the Ships and Aircraft of the U.S. Fleet Norman Polmar. Naval Institute Press, 2005. page 161

- "Navy has few FFG options to fill LCS gap". Navytimes.com. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "Mayport frigates may get reprieve".

- Faram, Mark D. "Keeping frigates running no easy feat for crews." Archived 28 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine Navy Times, 29 May 2012.

- "Decommissioning plan pulls all frigates from fleet by end of FY '15". Militarytimes.com. 2 July 2014. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- Retiring frigates may leave some missions unfilled Archived 28 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine - Navytimes.com, 26 July 2014

- U.S. Navy harvests decommissioned Frigates weapon systems for U.S. Coast Guard use - Navyrecognition.com, 26 October 2014

- Navy 'Taking a Hard Look' At Pulling Frigates Out of Mothballs - Military.com, 13 June 2017

- CNO: Navy ‘Taking a Hard Look’ at Bringing Back Oliver Hazard Perry Frigates, DDG Life Extensions as Options to Build Out 355 Ship Fleet - News.USNI.org, 13 June 2017

- SECNAV Spencer: Oliver Hazard Perry Frigates Could be Low-Cost Drug Interdiction Platforms - News.USNI.org, 20 September 2017

- Don't reactivate the old frigates, internal US Navy memo recommends - Defensenews.com, 13 November 2017

- "Undersecretariat of Turkish Defence Industries: GENESIS modernization program". Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- "MK 41 Vertical Launch Systems for Turkish Navy : Naval Forces : Defense News Air Force Army Navy News". Defencetalk.com. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- googletag.display, Defense Industry Daily staff. "Naval Swiss Army Knife: MK 41 Vertical Missile Launch Systems (VLS)". Defense Industry Daily. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - "FMS: Turkey Requests MK 41 Vertical Launch Systems". Deagel.com. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ">First Turkish Perry With Mk-41 VLS On". Turkishnavy.net. 19 March 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "Defence strategists lament ship sale". 26 December 2019.

- "SIPRI Arms Transfers Database - United States to Egypt; 1995-2005; Ships". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- Pakistan to get refurbished warship from US Times of India, 19 October 2008

- "Taiwan to buy Perry-class frigates from U.S." Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "Old US Navy frigates to be reactivated for delivery to Taiwan Navy". Naval Today. 22 July 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- "US-purchased warships inaugurated - Taipei Times". www.taipeitimes.com. 9 November 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- "SIPRI Arms Transfers Database - United States to Turkey; 1995-2005; Ships". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- "RIMPAC participants sink another ship in live-fire event". Naval Today. 20 July 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- Stancy Correll, Diana (22 September 2020). "Decommissioned guided-missile frigate Curts sunk during Valiant Shield exercise". Navy Times. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- "H.R.3470 - 113th Congress (2013-2014): To affirm the importance of the Taiwan Relations Act, to provide for the transfer of naval vessels to certain foreign countries, and for other purposes". 8 April 2014.

- Affairs, This story was written by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Sara B. Sexton, Commander, Task Force 70 Public. "SINKEX Conducted During Valiant Shield 2016". Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bahtić, Fatima (21 June 2022). "US Navy destroys Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigate during sinking exercise". Naval Today. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- U.S. offers two decommissioned frigates to Ukrainian Navy - Voronchenko, Interfax-Ukraine (20 November 2018)

- "The United States proposed the transfer of the Ukrainian Navy modern frigate | the Sivertelegram". Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- "Frigates - FFG". US Navy. 29 September 2015. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- "US, Pakistan Navies Come Together for Ceremony" Archived 24 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, NNS100901-09, Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class (SW) Jacob Sippel, Navy Public Affairs Support Element East Detachment Southeast, 1 September 2010

- "Wadsworth Finds New Life in Polish Navy" Archived 24 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, NNS110613-05, Ensign Adam Demeter, Commander, U.S. Naval Forces Europe and Africa/U.S. 6th Fleet Public Affairs, 13 June 2011

- Yaylalı, Devrim (6 October 2017). "The Sinking Of Ex-USS Duncan". Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- "Frigate Photo Index FFG-10 USS DUNCAN". www.navsource.org. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- "USS George Philip Decommissioned" Archived 24 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, NNS030328-14, Ensign Russell Childress, Commander, Navy Surface Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet Public Affairs, 28 March 2003

- "Bremerton mothball fleet continues to diminish" Archived 24 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Kitsap Sun Staff, Kitsap Sun, 30 April 2015

- "Decommissioned U.S. Navy Ship Lives On in Turkish Fleet" Archived 24 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, NNS020416-08, Naval Surface Force Atlantic Fleet Public Affairs, 16 April 2002

- "USS Estocin Decommissioned" Archived 24 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, NNS030406-02, Naval Station Mayport Public Affairs, 6 April 2003

- "HMAS Adelaide sunk off Avoca coast after dolphin delay", AAP, The Australian, 13 April 2011

- "HMAS Canberra scuttled off Victoria", ABC News, 4 October 2009

- "U.K. and U.S. conduct SINKEX during Atlantic Thunder 22", United States Navy, 23 September 2022

- "SEA 21 Navy Inactive Ships Office". Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- "Crew Departs USS Stephen W. Groves", Staff, The Florida Times-Union, 29 February 2012

- "Always victorious, always ready, Mayport frigate Hall decommissioned", Jeff Brumley, The Florida Times-Union, 9 March 2012

- "HMAS Sydney decommissioned after 32 years of service", ABC News, 30 November 2015

- Seiler, Melissa (30 May 2017). "Ex-HMAS Sydney not to be sunk for artificial reef but to be scrapped instead". dailytelegraph. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- "Ex-HMAS Sydney". Birdon.

- "Farewell USS Underwood", Lieutenant (junior grade) Kellye Quirk, USS Underwood Public Affairs, 13 March 2013

- "Second RIMPAC Sinking Exercise Concludes" Archived 22 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine, NNS160721-02, Rim of the Pacific Public Affairs, 21 July 2016

- Stancy Correll, Diana (22 September 2020). "Decommissioned guided-missile frigate Curts sunk during Valiant Shield exercise". Navy Times. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- "Fair Winds, USS Doyle", Ensign Benjamin Carroll, USS Doyle Public Affairs, 3 August 2011

- "Floating warship museum still eyed for Presque Isle Bay". goerie.com. 21 November 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- "RIMPAC participants sink another ship in live-fire event". Naval Today. 20 July 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- "USS Klakring Decommissioned at Naval Station Mayport" Archived 24 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, NNS130322-14, Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Sean Allen, 4th Fleet Public Affairs, 22 March 2013

- "RIMPAC Units Participate in Sinking Exercise", Commander, U.S. 3rd Fleet, 14 July 2016

- "USS De Wert Decommissioned in Mayport" Archived 24 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, NNS140404-17, Ensign Kierstin King, USS De Wert Public Affairs, 4 April 2014

- "SINKEX Conducted During Valiant Shield 2016" Archived 23 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, NNS160914-03, Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Sara B. Sexton, Commander, Task Force 70 Public Affairs, 14 September 2016

- "USS Nicholas Decommissioned" Archived 24 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, NNS140312-13, Lieutenant (junior grade) Christina M. Gibson, USS Nicholas Public Affairs, 12 March 2014

- Bahtić, Fatima (21 June 2022). "US Navy destroys Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigate during sinking exercise". Naval Today. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- "Robert G. Bradley is Decommissioned" Archived 24 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, NNS140328-14, Ensign Christopher M. Cate, USS Robert G. Bradley Public Affairs, 28 March 2014

- "Mayport warship decommissioned", WJXT News4Jax.com, 28 March 2014

- "USS Taylor (FFG 50) decommissions", Commander, Naval Surface Force Atlantic, 8 May 2015

- "Final West Coast Frigate, USS Gary, Decommissioned" Archived 31 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, NNS150724-01, Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Trevor Welsh, Naval Surface Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet Public Affairs, 24 July 2015

- "Last West Coast Frigate USS Gary Decommissioned Before Sale to Taiwan", Sam LaGrone, USNI News, 24 July 2015

- "Decommissioning ceremony held for USS Carr (FFG 52)", Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Darien G. Kenney, The Flagship, Military Newspapers of Virginia, 20 March 2013

- "USS Carr is officially decommissioned in special ceremony in Norfolk", Gabriella DeLuca, WTKR, 13 March 2013

- "Former Perry frigate USS Ford sunk in live-fire exercise off Guam". Naval Today. 2 October 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- "USS Elrod is Decommissioned" Archived 24 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, NNS150130-07, Ensign Mary C. Senoyuit, USS Elrod Public Affairs, 30 January 2015

- "Last Oliver Hazard Perry Frigate USS Simpson Leaves Service, Marked for Foreign Sale", Sam LaGrone, USNI News, 29 September 2015

- "End of era: Navy retires the USS Simpson, last modern ship to sink an enemy vessel", Andrew Pantazi, The Florida Times-Union, 29 September 2015

- "Navy Sinks Former Frigate USS Reuben James in Test of New Supersonic Anti-Surface Missile", Sam LaGrone, USNI News, 7 March 2016

- "The Once—and Future?—USS Samuel B. Roberts", Bradley Peniston, Defense One, 23 May 2015

- "USS Kauffman to be Decommissioned" Archived 22 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, NNS150917-15, USS Kauffman Public Affairs, 17 September 2015.

- "Frigate USS Kauffman Decommissions Today in Norfolk, Ship Set for Foreign Military Sale", Sam LaGrone, USNI News, 18 September 2015

- "Partner Nation Ships and Aircraft Participate in Sinking Exercise". Defense Visual Information Distribution Service. 15 July 2022.

- "U.S. Forces Conduct Sinking Exercise". Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- "S. 1683 - Summary". United States Congress. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- "H.R. 3470 - CBO" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- "CNO Richardson: Perry Frigates Only Inactive Hulls Navy Considering Returning to Active Fleet; DDG Life Extension Study Underway". News.usni.org. 16 June 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "Navy Won't Reactivate Perry Frigates for SOUTHCOM Mission". News.usni.org. 11 December 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

Further reading

- Bruhn, David D., Steven C. Saulnier, and James L. Whittington (1997). Ready to Answer All Bells: A Blueprint for Successful Naval Engineering. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-227-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Friedman, Norman (1982). U.S. Destroyers: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-733-X.

- Levinson, Jeffrey L. & Randy L. Edwards (1997). Missile Inbound. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-517-9.

- Peniston, Bradley (2006). No Higher Honor: Saving the USS Samuel B. Roberts in the Persian Gulf. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-661-5. Archived from the original on 12 July 2006. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- Snow, Ralph L. (1987). Bath Iron Works: The First Hundred Years. Bath, Maine: Maine Maritime Museum. ISBN 0-9619449-0-0.

- Thomas, Steve (November 2022). "America's Budget Frigate Programme– The Oliver Hazard Perry Class, Part 1". Marine News Supplement: Warships. 76 (11): S578–S589. ISSN 0966-6958.

- Wise, Harold Lee (2007). Inside the Danger Zone: The U.S. Military in the Persian Gulf 1987-88. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-970-5.

External links

- Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates at Destroyer History Foundation

- Oliver Hazard Perry class frigates: United States Navy Wikipedia book created 20 October 2009 at Internet Archive

- Oliver Hazard Perry class frigates 2015: United States Navy Wikipedia book created 22 January 2015 at Internet Archive

- Official U.S. Navy Fact File: Frigates Archived 2 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- FFG-7 OLIVER HAZARD PERRY-class: by the Federation of American Scientists

- MaritimeQuest Perry Class Overview

- Launch of FFG 58