Olmec figurine

Olmec figurines are archetypical figurines produced by the Formative Period inhabitants of Mesoamerica. While not all of these figurines were produced in the Olmec heartland, they bear the hallmarks and motifs of Olmec culture. While the extent of Olmec control over the areas beyond their heartland is not yet known, Formative Period figurines with Olmec motifs were widespread in the centuries from 1000 to 500 BC, showing a consistency of style and subject throughout nearly all of Mesoamerica.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

These figurines are usually found in household refuse, ancient construction fill, and, outside the Olmec heartland, graves.[1][2] However, many Olmec-style figurines, particularly those labelled as Las Bocas- or Xochipala-style, were recovered by looters and are therefore without provenance.

The vast majority of figurines are simple in design, often nude or with a minimum of clothing, and made of local terracotta. Most of these recoveries are mere fragments: a head, arm, torso, or a leg.[3] It is thought, based on wooden busts recovered from the water-logged El Manati site, that figurines were also carved from wood, but, if so, none have survived.

More durable and better known by the general public are those figurines carved, usually with a degree of skill, from jade, serpentine, greenstone, basalt, and other minerals and stones.

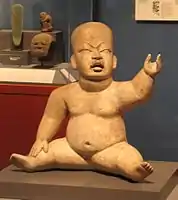

Baby-face figurines

The "baby-face" figurine is a unique marker of Olmec culture, consistently found in sites that show Olmec influence,[4] although they seem to be confined to the early Olmec period and are largely absent, for example, in La Venta.[5]

These ceramic figurines are easily recognized by the chubby body, the baby-like jowly face, downturned mouth, and the puffy slit-like eyes. The head is slightly pear-shaped, likely due to artificial cranial deformation.[6] They often wear a tight-fitting helmet not dissimilar to those worn by the Olmec colossal heads.[7] Baby-face figurines are usually naked, but without genitalia.[8] Their bodies are rarely rendered with the detail shown on their faces.

Also called "hollow babies", these figurines are generally from 25–35 cm (9.8–13.8 in) high[9] and feature a highly burnished white- or cream-slip. They are only rarely found in archaeological context.[10]

Archaeologist Jeffrey Blomster divides baby-face figurines into two groups based on several features. Among the many distinguishing factors, Group 1 figurines more closely mirror the characteristics of Gulf Coast Olmec artifacts. Group 2 figurines are also slimmer than those of Group 1, lacking the jowly face or fleshy body, and their bodies are larger in proportion to their heads.[11]

Given the sheer numbers of baby-face figurines unearthed, they undoubtedly fulfilled some special role in the Olmec culture. What they represented, however, is not known. Michael Coe, says "One of the great enigmas in Olmec iconography is the nature and meaning of the large, hollow, whiteware babies".[12]

Elongated man

Another common figurine style features standing figurines in a stiff artificial pose and characterized by their thin limbs, elongated, bald, flat-topped heads, almond-shaped eyes, and downturned mouths. The figurines' legs are usually separated, often straight, sometimes bent. Toes and fingers, if shown at all, are frequently represented by lines.

It has been theorized that the elongated, flat-topped heads are reflective of the practice of artificial cranial deformation, as found in the Tlatilco burials of the same period or among the Maya of a later era.[14] No direct evidence of this practice has been found in the Olmec heartland, however.

The ears often have small holes for ear flares or other ornaments. These figurines may have therefore once worn earrings and even clothes made of perishable materials. It has been proposed that these figurines had multiple outfits for different ritual occasions – as Richard Diehl puts it, "a pre-Columbian version of Barbie's Ken".[15]

These figurines are usually carved from jade and well under 1 ft (30 cm) in height. For another example, see this Commons photo.

Offering 4 at La Venta

At the La Venta archaeological site, archaeologists found what they subsequently named "Offering 4". These figurines had been ritually buried in a deep, narrow hole, and covered over with three layers of colored clay. At some point after the original burial, someone dug a small hole down just to the level of their heads and then refilled it.[16]

Offering 4 consists of sixteen male figurines positioned in a semicircle in front of six jade celts, perhaps representing stelae or basalt columns. Two of the figurines were made from jade, thirteen from serpentine, and one of reddish granite. This granite figurine one was positioned with its back to the celts, facing the others. All of the figurines had similar classic Olmec features including bald elongated heads. They had small holes for earrings, their legs were slightly bent, and they were undecorated – unusual if the figurines were gods or deities – but instead covered with cinnabar.[17]

Interpretations abound. Perhaps this particular formation represents a council of some sort—the fifteen other figurines seem to be listening to the red granite one, with the celts forming a backdrop. One of the most striking offerings found at La Venta, the celts in Offering Number 4, depict a person with a ceremonial headdress “flying” and also the maize deity. There appears to be a definite symbolic link here, but it is unclear whether it is tied to the Olmec rudimentary writing system.[18] To the red granite figurine's right, there seems be a line of three figurines filing past him. Another researcher has suggested that the granite figure is an initiate.

As the name implies, Offering 4 is one of many ritual offerings uncovered at La Venta, including the four Massive Offerings and four mosaics. Why such works would be buried continues to generate much speculation.

"Were-jaguar" motif

The so-called were-jaguar motif runs through much of Olmec art, from the smallest jade to some of the largest basalt statues. The motif is found inscribed on celts, votive axes, masks, and on "elongated man" figurines.

Also termed, somewhat more neutrally, the "composite anthropomorph"[19] or the "rain baby",[20] the were-jaguar's body, if shown, is baby- or childlike. Its eyes are almond-shaped – or occasionally slit-like.[21] Its nose is human. Its downturned mouth is open, as if in mid-squall. The upper lip is everted and toothless gums are often visible. Olmec motifs associated with the were-jaguar include a cleft on the head or headdress, a headband, and cross-bars.[22]

Most were-jaguar figurines show an inert were-jaguar baby being held by an adult.

Transformation figures

Many other Olmec figurines combined human and animal features, including this were-eagle (left). Although figurines showing such combinations of features are generally termed "transformation figures", some researchers argue that they represent humans in animal masks or animal suits, while others state that they likely represent shamans.[23]

This transformation figure displays bat-like features. Most common, however, is the jaguar transformation figurine (see Commons photo), which show a wide variety of styles, ranging from human-like figurines to those that are almost completely jaguar, and several where the subject appears to be in a stage of transformation.[24]

Naturalistic figurines

Despite the many stylised figurines, Olmec-period artisans and artist also portrayed humans naturalistically with "a most extraordinary realistic technique".[25] The lead photo for this article shows a number of tiny naturalistic figurines.

Dwarf or fetal-style figurines

Another pervasive Olmec figurine type features crouching figurines with thin bodies and over-large oval heads with small noses and receding chins.[26] Some researchers such as Miguel Covarrubias generally characterise these figurines as "dwarfs".[27] many others, also including Covarrubias, see evidence of "what looks like pre-natal posture".[28] In a 1999 article, Carolyn Tate and Gordon Bendersky analysed head-to-body ratios and concluded that these figurines are naturalistic sculptures of fetuses, and discuss the possibility of infanticide and infant sacrifice.[29]

Gallery

This rather unlively figurine belongs to Blomster's Group 2.

This rather unlively figurine belongs to Blomster's Group 2._-_San_Jose%252C_C_R.jpg.webp) A baby-face figurine from the Museo Nacional del Jade, San Jose, Costa Rica.

A baby-face figurine from the Museo Nacional del Jade, San Jose, Costa Rica. A ceramic figurine showing typical "baby-face" characteristics, Snite Museum of Art

A ceramic figurine showing typical "baby-face" characteristics, Snite Museum of Art

See also

- Olmec influences on Mesoamerican cultures - a discussion of Olmec influence outside the Olmec heartland

Notes

- Pool, Christopher A. (Apr 2017). Insoll, Timothy (ed.). "Mesoamerica—Olmec Figurines". The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Figurines. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199675616.013.012.

- Cheetham, David (2009). "Early Olmec Figurines from Two Regions: Style as Cultural Imperative" (PDF). University Press of Florida.

- Castro-Leal, p. 143 .

- Scott, p. 268.

- Coe (1989), p. 77.

- Pohorilenko, p. 121.

- Pohorilenko, p. 121 .

- Blomster (1998), p. 311, says "Sex or gender do not appear to be indicated on any of these objects.".

- Blomster (2002), p. 173.

- Blomster (1998).

- Blomster (2002).

- Coe (1989), p. 77.

- Bradley (2005) p. 25.

- Diehl, p. 122.

- Diehl, p. 122.

- Pool, p. 164, who refers to Drucker, Heizer, and Squier (1959) Excavations at La Venta, Tabasco, Smithsonian.

- Pool, p. 164.

- Xu 1998

- Porhilenko.

- Miller & Taube. Joralemon (1996) similarly refers to this combination of features as the "storm god".

- Miller & Taube, p. 126.

- Miller & Taube, p. 126.

- Diehl, p. 106.

- Miller & Taube state that the jaguar is the primary subject of transformation figures, p. 103.

- Kubler, p. 12.

- Pohorilenko, p. 122.

- Covarrubias, p. 64. Pohorilenko, p. 122, also describes these crouching figurines as dwarfs.

- Covarrubias, p. 57.

- Tate & Bendersky.

References

- Bailey, Douglass (2005). Prehistoric Figurines: Representation and Corporeality in the Neolithic. Routledge Publishers. ISBN 0-415-33152-8.

- Blomster, Jeffrey (1998). "Context, Cult, and Early Formative Period Public Ritual in the Mixteca Alta, Analysis of a Hollow-baby Figurine from Etlatongo, Oaxaca". Ancient Mesoamerica. 9 (2): 309–326. doi:10.1017/S0956536100002017. S2CID 163048092. (subscription required)

- Blomster, Jeffrey (2002). "What and Where is Olmec Style? Regional perspectives on Hollow Figurines in Early Formative Mesoamerica". Ancient Mesoamerica. 13 (2): 171–195. doi:10.1017/S0956536102132196. S2CID 161972379. (subscription required)

- Bradley, Douglas E; Joralemon, Peter David (1993). "The Lords of Life: The Iconography of Power and Fertility in Preclassic Mesoamerica". Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Bradley, Douglas E.; et al. (2005). Celebrating Twenty-five Years in the Snite Museum of Art: 1980-2005. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. ISBN 978-0-9753984-1-8.

- Castro-Leal, Marcia (1996). "The Olmec Collections of the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City". In Benson, EP; de la Fuente, B. (eds.). Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico. Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art. pp. 139–143. ISBN 0-89468-250-4.

- Coe, Michael D (1989). "The Olmec Heartland: Evolution of Ideology". In Sharer, Robert J.; Grove, David (eds.). Regional Perspectives on the Olmec. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36332-7.

- Covarrubias, Miguel (1957). Indian Art of Mexico and Central America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. OCLC 171974.

- Kubler, George (1990) [first pub. 1962]. The Art and Architecture of Ancient America (3rd ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05325-8. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- Miller, Mary; Taube, Karl (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6. OCLC 27667317.

- Pohorilenko, Anatole (1996). "Portable Carvings in the Olmec Style". In Benson, EP; de la Fuente, B. (eds.). Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico. Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art. ISBN 0-89468-250-4.

- Pool, Christopher A (2007). Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78882-3. OCLC 68965709.

- Scott, Sue (2000). "Figurines, Terracotta". In Evans, Susan (ed.). Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America. Taylor & Francis. p. 266. ISBN 9780815308874. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- Solis, Felipe (1994). "La Costa del Golfo: el arte del centro de Veracruz y del mundo huasteco". In García, María Luisa Sabau (ed.). México en el mundo de las colecciones de arte: Mesoamerica (in Spanish). Vol. 1. México, D.F.: Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas-UNAM, and Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. pp. 183–241. ISBN 968-6963-36-7. OCLC 33194574.

- Tate, Carolyn; Bendersky, Gordon (1999). "Olmec Sculptures of the Human Fetus". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 42 (Spring): 1–20. doi:10.1353/pbm.1999.0017. PMID 12966945. S2CID 33648532. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- Xu, Mike H. (1998). "La Venta Offering No.4: A Revelation of Olmec Writing?". Pre-Columbiana. 1 (1–2): 131–143.

External links

- Comprehensive catalogue of Olmec figurines (and figurine fragments) — fine photos of artifacts recovered at the Olmec heartland site of San Andrés.

— This collection details the entire range of figurines & figurine fragments — while other books and articles focus on the more artistic and complete figurines.