Oba (ruler)

Oba means "ruler" in the Yoruba and Bini languages. Kings in Yorubaland, a region which is in the modern republics of Benin, Nigeria and Togo, make use of it as a pre-nominal honorific. Examples of Yoruba bearers include Oba Ogunwusi of Ile-Ife, Oba Aladelusi of Akure, and Oba Akiolu of Lagos. An example of a Bini bearer is Oba Ewuare II of Benin.

The title is distinct from that of Oloye in Yorubaland, which is itself used in like fashion by subordinate titleholders in the contemporary Yoruba chieftaincy system.[1]

Aristocratic titles among the Yoruba

The Yoruba chieftaincy system can be divided into four separate ranks: royal chiefs, noble chiefs, religious chiefs and common chiefs. The royals are led by the obas, who sit at the apex of the hierarchy and serve as the fons honorum of the entire system. They are joined in the class of royal chiefs by the titled dynasts of their royal families. The three other ranks, who traditionally provide the membership of a series of privy councils, sects and guilds, oversee the day-to-day administration of the Yoruba traditional states and are led by the iwarefas, the arabas and the titled elders of the kingdoms' constituent families.[2]

Oba

There are two different kinds of Yoruba monarchs: The kings of Yoruba clans, which are often simply networks of related towns (For example, the oba of the Ẹ̀gbá bears the title "Aláké" because his ancestral seat is the Aké quarter of Abẹ́òkúta, hence the title Aláké, which is Yoruba for One who possesses Aké. The Ọ̀yọ́ ọba, meanwhile, bears the title "Aláàfin", which means One who possesses the palace) and the kings of individual Yoruba towns, such as that of Ìwó — a town in Osun State — who bears the title "Olúwòó" (Olú ti Ìwó, lit. Lord of Ìwó).[3]

The first-generation towns of the Yoruba homeland, which encompasses large swathes of Benin, Nigeria, and Togo, are those with obas who generally wear beaded crowns; the rulers of many of the 'second generation' settlements are also often obas. Those that remain and those of the third generation tend to only be headed by the holders of the title "Baálẹ̀" (lit. Master of the land), who do not wear crowns and who are, at least in theory, the reigning viceroys of people who do.

Oloye

All of the subordinate members of the Yoruba aristocracy, both traditional chieftains and honorary ones, use the pre-nominal "Olóyè" (lit. Owner of a title, also appearing as "Ìjòyè") in the way that kings and queens regnant use 'Ọba'. It is also often used by princes and princesses in colloquial situations, though the title that is most often ascribed to them officially is "Ọmọba" (lit. Child of a Monarch, sometimes rendered alternatively as "Ọmọọba", "Ọmọ ọba" and "Ọmọ-ọba"). The wives of kings, princes and chiefs of royal background usually make use of the title "Olorì" (the equivalent of Princess Consort), though some of the wives of dynastic rulers prefer to be referred to as "Ayaba" (the equivalent of Queen Consort). The wives of the non-royal chiefs, when themselves titleholders in their own right, tend to use the honorific "Ìyálóyè" (lit. Mother who owns a title) in their capacities as married chieftesses.

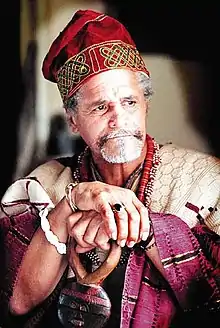

The Oba's crown

The bead-embroidered crown with beaded veil, foremost attribute of the Oba, symbolizes the aspirations of a civilization at the highest level of authority. In his seminal article on the topic, Robert F. Thompson writes, "The crown incarnates the intuition of royal ancestral force, the revelation of great moral insight in the person of the king, and the glitter of aesthetic experiences."[4]

Royal duties

%252C_Cmdr._Jeffrey_Wolstenholme%252C_presents_the_Oba_of_Nigeria%252C_with_a_ship's_plaque_during_the_ship's_visit.jpg.webp)

The role of the oba has diminished with the coming of colonial and democratic institutions. However, an event that still has symbolic prestige and capital is that of chieftaincy title-taking and awarding. This dates back to the era of the Oyo warrior chiefs and palace officials in the medieval period, when powerful individuals of varied ancestries held prominent titles in the empire. In Yorubaland, like in many other areas of Benin, Nigeria and Togo, chieftaincy titles are mostly given to successful men and women from within a given sub-sectional territory, although it is not unheard of for a person from elsewhere to receive one. The titles also act as symbolic capital that can be used to gain favour when desired by the individual oba that awarded them, and sometimes vice versa. During any of the traditional investiture ceremonies for the chiefs-designate, the oba is regarded by the Yoruba as the major centre of attention, taking precedence over even the members of the official governments of any of the three countries if they are present. As he leads the procession of nominees into a specially embroidered dais in front of a wider audience of guests and well-wishers, festivities of varied sorts occur to the accompaniment of traditional drumming. Emblems are given out according to seniority, and drapery worn by the oba and chiefs are created to be elaborate and also expensive. Most of the activities are covered by the local media and enter the public domain thereafter. Only the secret initiations for traditional chiefs of the highest rank are kept a secret from all outsiders. Ceremonies such as this, and the process of selection and maintenance of networks of chiefs, are two of the major sources of power for the contemporary royals of West Africa.[5]

Priestly duties

As a sacred ruler, the oba is traditionally regarded by the Yoruba as the ex officio chief priest of all of the Orisha sects in his or her domain. Although most of the day-to-day functions of this position are delegated in practice to such figures as the arabas, certain traditional rites of the Yoruba religion can only be performed by the oba, and it is for this reason that the holders of the title are often thought of as being religious leaders in addition to being politico-ceremonial monarchs.

See also

References

- Blair, Major J.H., Intelligence Report on Abeokuta: 65 year anniversary reprint edition (2002), p. 3.

- Sotunde, F.I., Egba Chieftaincy Institution (2002), Appendix X.

- Jr, Everett Jenkins (2015-07-11). Pan-African Chronology II: A Comprehensive Reference to the Black Quest for Freedom in Africa, the Americas, Europe and Asia, 1865-1915. McFarland. p. 220. ISBN 978-1-4766-0886-0.

- Thompson, Robert F. (1972). Douglas Fraser and Herbert M. Cole (ed.). African art & leadership. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 227–260. ISBN 0299058204.

- Lionel Caplan, Humphrey Fisher, David Parkin; The Politics of Cultural Performance. Berghahn Books, 1996, p 30-37.