One Hundred and One Dalmatians

One Hundred and One Dalmatians (also simply known as 101 Dalmatians) is a 1961 American animated adventure comedy film produced by Walt Disney Productions and released by Buena Vista Distribution. Based on Dodie Smith's 1956 novel The Hundred and One Dalmatians, it is the 17th Disney animated feature film. The film was directed by Hamilton Luske, Clyde Geronimi, and Wolfgang Reitherman, and was written by Bill Peet.[lower-alpha 1] With the voices of Rod Taylor, J. Pat O'Malley, Betty Lou Gerson, Martha Wentworth, Ben Wright, Cate Bauer, David Frankham, and Frederick Worlock, the film's plot follows a litter of fifteen Dalmatian puppies, who are kidnapped by the obsessive heiress Cruella de Vil, wanting to make their fur into coats. Their parents, Pongo and Perdita, set out to save their puppies from Cruella, in the process rescuing eighty-four additional ones, bringing the total of Dalmatians to one hundred and one.

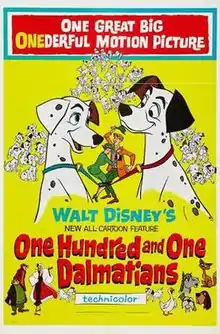

| One Hundred and One Dalmatians | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Screenplay by | Bill Peet (uncredited)[1] |

| Story by | Bill Peet |

| Based on | The Hundred and One Dalmatians by Dodie Smith |

| Produced by | Walt Disney |

| Starring | |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | George Bruns |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 79 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.6 million[2] |

| Box office | $303 million[3] |

One Hundred and One Dalmatians was released to theaters on January 25, 1961,[4] to critical acclaim, and was a box office success, pulling the studio out of the financial slump caused by Sleeping Beauty, a costlier production released two years prior.[5] Grossing $14 million domestically in its original theatrical run, it became the eighth-highest-grossing film of the year in the North American box office. Aside from its box-office revenue, the employment of inexpensive animation techniques—such as using xerography during the process of inking and painting traditional animation cels—kept production costs down. Counting reissues, the film grossed $303 million worldwide, and is the twelfth-highest-grossing film in the North American box office when adjusted for inflation.

The success of the film made Disney expand it into a media franchise, with a live-action remake released in 1996, followed by a sequel in 2000. A direct-to-video animated sequel to the 1961 film, 101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure, was released in 2003. Two animated television series based on the franchise were also produced, with 101 Dalmatians: The Series in 1997 and 101 Dalmatian Street in 2019. A live-action reboot, Cruella, was released in 2021.

Plot

Aspiring songwriter Roger Radcliffe lives in London, in a bachelor flat with his pet dalmatian, Pongo. Deciding both of them need a "mate", Pongo watches women and their dogs in the street. Noticing Anita and her Dalmatian Perdita, he drags Roger to the park to arrange a meeting. Roger and Anita fall in love, and soon marry, with Pongo and Perdita attending.

The pair hires a nanny and moves to a small townhouse near Regent's Park. After Perdita becomes pregnant with a litter of 15 puppies, Anita's fur-obsessed former schoolmate, Cruella de Vil, arrives and demands to know when the puppies will arrive. Roger responds by writing a jazzy song mocking her. When the puppies are born, Cruella returns, demanding to buy them. Roger firmly denies her offer; Cruella, refusing to take no for an answer, swears revenge and storms out.

Several weeks later, Cruella hires brothers Horace and Jasper Baddun, two burglars, to steal the puppies. When Scotland Yard is unable to find the puppies, Pongo and Perdita use the "Twilight Bark", a canine gossip line, to solicit help from the other dogs in London.

Colonel, an Old English Sheepdog, along with his compatriot Sergeant Tibbs, a tabby cat, investigate the nearby "Old De Vil Place", where puppies had been heard barking two nights earlier. Tibbs learns they are going to be made into dog-skin fur coats, after which Colonel sends word back to London. Pongo and Perdita leave through a back window and begin a long cross-country journey, crossing an icy river and running through the snow toward Suffolk.

Meanwhile, Tibbs overhears Cruella ordering the Baddun brothers to kill the puppies that night out of fear the police will soon find them. In response, Tibbs helps the puppies escape through a hole in the wall, but the Baddun brothers notice and give chase. Pongo and Perdita break into the house and confront the Badduns just as they are about to kill the puppies. While the adult dogs attack the two men, Colonel and Tibbs guide the puppies from the house. Following a happy reunion with their own puppies, Pongo and Perdita discover there are 84 more puppies with them. Shocked at Cruella's plans, they decide to adopt all of them, certain that Roger and Anita would never reject them.

The Dalmatians start their homeward trek, pursued by the Baddun brothers. They take shelter from a blizzard in a dairy farm with a friendly collie and three cows, then make their way to Dinsford, where they meet a Black Labrador waiting for them in a blacksmith's shop. Cruella and the Baddun brothers arrive, prompting Pongo to have his entire family roll in a sooty fireplace to disguise themselves as other Labradors. The Labrador helps them board a moving van bound for London, but melting snow falls on Lucky and clears the soot off of him. Enraged, Cruella pursues the van in her car and rams it to try and force it off the road, but the Badduns, who try to cut it off from above, end up colliding with her. Both vehicles crash into a ditch. Cruella yells in frustration at the pair as the van drives off.

In London, a depressed Nanny and the Radcliffes try to enjoy Christmas, and the wealth they have acquired from the song about Cruella, which has become a big radio hit. The soot-covered Dalmatians suddenly flood the house. Upon removing the soot and counting the massive family of dogs, Roger chooses to use his songwriting royalties to buy a big house in the country so they can keep all 101 dalmatians.

Cast

- Rod Taylor as Pongo, Roger's playful and headstrong pet Dalmatian, Perdita's mate, the father of fifteen, and adopted father of the eighty-four orphaned puppies. He also serves as the film's narrator.

- J. Pat O'Malley as Jasper Baddun, Horace's tall and lean brother, who kidnaps the Dalmatians puppies on Cruella's orders. He drives a brown van with loose/broken fenders.

- O'Malley also voiced the Colonel, an Old English Sheepdog who helps Pongo and Perdita find their puppies.[6]

- Betty Lou Gerson as Cruella de Vil, a ruthless and selfish socialite and Anita's former schoolmate, who obsessively wants to turn the fur of Dalmatians puppies into a coat. She drives a burgundy car similar to a Mercedes-Benz 500K Cabriolet.

- Gerson also voiced Miss Birdwell, a panelist on the show "What's My Crime?".[7]

- Martha Wentworth as Nanny,[8] the Radcliffes' maternal and fussy cook and housekeeper. She is an amalgamation of the characters "Nanny Cook" and "Nanny Butler" from the original novel.[9]

- Wentworth also voiced Lucy,[10] the white goose and friend of Old Towser.

- Ben Wright as Roger Radcliffe,[8] Pongo's laid-back and creative owner and Anita's husband, who works as a songwriter.

- Cate Bauer as Perdita, Anita's poised and affectionate pet Dalmatian, Pongo's mate, the mother of fifteen, and adopted mother of the eighty-four orphaned puppies. She is an amalgamation of the characters "Perdita" and "Missis" from the original novel.[11]

- David Frankham as Sergeant Tibbs, a tabby cat who is the first to discover the puppies' whereabouts and helps them escape from the Hell Hall.

- Frankham also voiced Scottie,[12] Danny's Skye Terrier friend.

- Frederick Worlock as Horace Baddun,[13] Jasper's short and plump brother, who kidnaps the Dalmatian puppies on Cruella's orders.

- Worlock also voiced Inspector Graves,[14] a panelist on the show "What's My Crime?".

- Lisa Davis as Anita Radcliffe, Perdita's gentle and intelligent owner, Roger's wife, and Cruella's former schoolmate, because of which she, unlike other characters, feels inclined to give her the benefit of the doubt.

- Tom Conway as the Collie[13] who offers the Dalmatians shelter for the night at a dairy barn.

- Conway also voiced the Quizmaster,[10] the host of "What's My Crime?".

- Tudor Owen as Old Towser,[10] a Bloodhound who helps spread the news about the stolen puppies.

- George Pelling as Danny, a Great Dane[13] who aids Pongo and Perdita and is the first dog to answer their Twilight Bark message.

- Ramsay Hill as the Labrador Retriever[14] who helps load puppies into the moving van in Dinsford.

- Thurl Ravenscroft as Captain,[10] a gray horse and comrade of Sergeant Tibbs and Colonel, who aids Pongo and Perdita.

Martha Wentworth, Queenie Leonard, and Marjorie Bennett provided voices for Queenie, Princess, and Duchess, cows from a dairy barn where Dalmatians stay for the night while escaping from Cruella and the Badduns.[10] Mickey Maga, Barbara Beaird, Mimi Gibson, and Sandra Abbott voiced Patch, Rolly, Lucky, and Penny, the Dalmatian puppies from Pongo and Perdita's litter.[14] Barbara Luddy and Rickie Sorensen provided voices for Rover and Spotty, two of the eighty-four Dalmatian puppies that were bought by Cruella.[14][15] Paul Frees voiced Dirty Dawson, the villain in the "Thunderbolt" TV show; he has no spoken dialogue in the film, only laughter.[14]

Lucille Bliss, who had voiced Anastasia Tremaine in Cinderella (1950), performed the "Kanine Krunchies" jingle in a TV commercial;[16] Jeanne Gayle, the wife of the film's composer George Bruns, performed the radio version of "Cruella De Vil" song used in the film's final sequence.[10]

Production

Story development

In 1956, the children's novel The Hundred and One Dalmatians by Dodie Smith had been published to an immediate success.[17] Smith's friend, Charles Brackett, brought it to the attention of Walt Disney in February 1957, who saw the book's potential for an animated feature[18] and, after several months of negotiations, obtained the rights for $25,000.[19] Bill Peet was assigned to single-handedly write the story,[20] which marked the first time that the story for a Disney animated film was written by one person.[21] Disney also tasked him to write a detailed screenplay first before storyboarding, and, since he never learned to use a typewriter, Peet wrote the initial draft by hand on legal paper.[1] The manuscript was completed and typed up within two months, after which, having received Disney's approval, Peet began storyboarding and was charged with recording the voice-over process.[22]

Peet closely followed the plot of Smith's original novel, but condensed some of its elements while enlarging others,[1] which included eliminating Cruella's husband and cat,[11] as well as merging two Dalmatian mothers, birth mother Missis and adopted mother Perdita, into one character.[23] Another notable character loss was Cadpig, the female runt of Pongo and Missis' puppies, whose traits were transferred to Lucky in the film, such as him being the puppy who nearly dies right after birth, but survives.[9][lower-alpha 2] The Colonel's cat assistant was re-gendered from being a female by the name of Lieutenant Willow in the book, and Horace Baddun was renamed from Saul to presumably make him sound more akin in tone to Jasper. Among other things, Peet retained a scene from the original book in which Pongo and Perdita exchange wedding vows in unison with their owners, who were also renamed from Mr. and Mrs. Dearly to Roger and Anita Radcliffe.[9] However, after the censor board warned that it might offend certain religious audiences if the animals repeated the exact words of a solemn religious ceremony, it was reworked to be less religious, down to having Roger and Anita dressed in formal clothes.[24] Also, the film's original ending involved the newly rich Roger selling his song about Cruella and buying the Hell Hall to turn it into a Dalmatian Plantation, with Pongo and Perdita expecting another litter of puppies. It was ultimately cut short and rewritten to have Dalmatians reunite with their owners after they escape from Cruella.[25]

Although Disney had not been as involved in the production of the animated films as frequently as in previous years nevertheless, he was always present at story meetings.[26] When Peet sent Dodie Smith some drawings of the characters, she wrote back saying that he had improved her story and that the designs looked better than the illustrations in the book.[18]

Art direction

After Sleeping Beauty (1959) disappointed at the box-office, there was some talk of closing down the animation department at the Disney studio.[26] During the production of it, Disney told animator Eric Larson: "I don't think we can continue; it's too expensive."[27] Despite this, he still had deep feelings towards animation because he had built the company upon it.[26]

Ub Iwerks, in charge of special processes at the studio, had been experimenting with Xerox photography to aid in animation. By 1959, he had modified a Xerox camera to transfer drawings by animators directly to animation cels, eliminating the inking process, thus saving time and money while preserving the spontaneity of the penciled elements.[28] However, because of its limitations, the camera was unable to deviate from a black scratchy outline and lacked the fine lavish quality of hand inking.[28] Disney would first use the Xerox process for a thorn forest in Sleeping Beauty,[27] and the first production to make full use of the process was Goliath II.[28] For One Hundred and One Dalmatians, one of the benefits of the process was that it was a great help towards animating the spotted dogs. According to Chuck Jones, Disney was able to complete the film for about half of what it would have cost if they had had to animate all the dogs and spots.[29]

Ken Anderson proposed the use of the Xerox on Dalmatians to Walt, who was disenchanted with animation by then, and replied "Ah, yeah, yeah, you can fool around all you want to".[30] For the stylized art direction, Anderson took inspiration from British cartoonist Ronald Searle,[31] who once advised him to use a Mont Blanc pen and India ink for his artwork. In addition to the character animation, Anderson also sought to use Xerography on "the background painting because I was going to apply the same technique to the whole picture."[30] Along with color stylist Walt Peregoy, the two had the line drawings be printed on a separate animation cel before being laid over the background, which gave the appearance similar to the Xeroxed animation.[26][32] Disney disliked the artistic look of the film and felt he was losing the "fantasy" element of his animated films.[26] In a meeting with Anderson and the animation staff concerning future films, Walt said, "We're never gonna have one of those goddamned things" referring to Dalmatians and its technique, and stated, "Ken's never going to be an art director again."[30]

Ken Anderson took this to heart, but Walt eventually forgave him on his final trip to the studio in late 1966. As Anderson recalled in an interview:

He looked very sick. I said, "Gee, it's great to see you, Walt," and he said, "You know that thing you did on Dalmatians." He didn't say anything else, but he just gave me this look, and I knew that all was forgiven and in his opinion, maybe what I did on Dalmatians wasn't so bad. That was the last time I ever saw him. Then, a few weeks later, I learned he was gone.[26]

Casting

For the roles of dogs, the filmmakers deliberately cast actors with deeper voices than their human owners, so they had more power.[33] Rod Taylor, who had extensive radio experience, was one of the first performers cast in the film.[10] J. Pat O'Malley was a regular voice actor for the Disney studio, having previously voiced several characters in both The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949) and Alice in Wonderland (1951), and was one of Walt Disney's personal favorites.[10] Betty Lou Gerson, who was previously the narrator for Cinderella (1950), auditioned for the role of Cruella de Vil in front of Marc Davis, the character's supervising animator, and sequence director Wolfgang Reitherman, and immediately landed it.[34] While searching for the right accent of the character, she landed on a "phony theatrical voice, someone who's set sail from New York but hasn't quite reached England".[35] During the recording process, Gerson was thought to be imitating Tallulah Bankhead,[36] but she later disputed that she "didn't intentionally imitate her… We both had phony English accents on top of our Southern accents and a great deal of flair. So our voices came out that way".[37] Gerson finished her recording sessions in fourteen days.[34] Lisa Daniels was originally cast in the role of Perdita and recorded about the third of her lines but then got married and moved to New York, with Bauer replacing her for the rest of the film.[10] David Frankham was cast as Sergeant Tibbs in the spring of 1959 and finished his recording within three sessions.[38] Disney originally had Lisa Davis read for the role of Cruella De Vil, but she did not think that she was right for the part, and wanted to try reading the role of Anita instead.[39] Disney agreed, and, after they read the script for a second time, she landed the part.[40] Davis also provided some of live-action reference for the character.[41] For the roles of dogs, the filmmakers deliberately cast actors with deeper voices than their human owners, so they had more power.[33]

Live-action reference

As with the previous Disney films, actors provided live-action reference in order to determine what would work before the animation process begun. Actress Helene Stanley performed the live-action reference for the character of Anita. She did the same work for the characters of Cinderella and Princess Aurora in Sleeping Beauty.[42] Meanwhile, Mary Wickes provided the live-action reference for Cruella de Vil.[43]

Character animation

Marc Davis was the sole animator on Cruella De Vil. During production, Davis claimed her character was partly inspired by Bette Davis (no relation), Rosalind Russell, and Tallulah Bankhead. He took further influence from her voice actress, Betty Lou Gerson, whose cheekbones he added to the character. He later complimented, "[t]hat [her] voice was the greatest thing I've ever had a chance to work with. A voice like Betty Lou's gives you something to do. You get a performance going there, and if you don't take advantage of it, you're off your rocker".[44] While her hair coloring originated from the illustrations in the novel, Davis found its disheveled style by looking "through old magazines for hairdos from 1940 till now". Her coat was exaggerated to match her oversized personality, and the lining was red because "there's a devil image involved".[45]

Music

To have music involved in the narrative, Peet used an old theater trick by which the protagonist is a down-and-out songwriter. However, unlike the previous animated Disney films at the time, the songs were not composed by a team, but by Mel Leven who composed both lyrics and music.[25] Previously, Leven had composed songs for the UPA animation studio in which animators, who transferred to work at Disney, had recommended him to Walt.[46] His first assignment was to compose "Cruella de Vil," of which Leven composed three versions. The final version used in the film was composed as a "bluesy number" before a meeting with Walt in forty-five minutes.[25]

The other two songs included in the film are "Kanine Krunchies Jingle" (sung by Lucille Bliss, who voiced Anastasia Tremaine in Disney's 1950 film Cinderella), and "Dalmatian Plantation" in which Roger sings only two lines at its closure. Leven had also written additional songs that were not included in the film. The first song, "Don't Buy a Parrot from a Sailor," a cockney chant, was meant to be sung by Jasper and Horace at the De Vil Mansion. A second song, "Cheerio, Good-Bye, Toodle-oo, Hip Hip!" was to be sung by the dalmatian puppies as they make their way into London.[47] A third song titled "March of the One Hundred and One" was meant for the dogs to sing after escaping Cruella by van. Different, longer versions of "Kanine Krunchies Jingle" and "Dalmatian Plantation" appear on the Disneyland Records read-along album based on the film.[48]

The Sherman Brothers wrote a title song, "One Hundred and One Dalmatians", but it was not used in the film.[49] The song has been released on other Disney recordings, however.[48][50]

Release

One Hundred and One Dalmatians was first released in theaters on January 25, 1961. The film was re-released theatrically in 1969, 1979, 1985, and 1991.[51] The 1991 reissue was the 20th highest-grossing film of the year for domestic earnings.[52] As part of Disney's 100th anniversary the film was re-released in cinemas across the UK on September 8, 2023 for one week.[53]

Home media

One Hundred and One Dalmatians was first released on VHS on April 10, 1992, as part of the Walt Disney Classics video series.[54] By June 1992, it had sold 11.1 million copies.[55] At the time, it was the sixth best-selling video of all time.[56] It was re-released on March 9, 1999, as part of the Walt Disney Masterpiece Collection video series. Due to technical issues, it was later released on LaserDisc and was delayed numerous times before its release on DVD. The film was re-released on VHS, and for the first time on DVD, in December 1999, as a Walt Disney Limited Issue for a limited 60-day time period before going into moratorium.[57] A two-disc Platinum Edition DVD was released on March 4, 2008. It was released on Blu-ray Disc in the United Kingdom on September 3, 2012.[58] A Diamond Edition Blu-ray of the film was released in North America on February 10, 2015. A Limited Edition from Disney Movie Club was released on Blu-ray and DVD combo on November 6, 2018. Then it was re-released on HD digital download and Blu-ray on September 24, 2019, as part of the Walt Disney Signature Collection.[59]

Reception

Box office

During its initial theatrical run, the film grossed $14 million in the United States and Canada,[60] which generated $6.2 million in distributor rentals.[61] It was also the most popular film of the year in France, with admissions of 14.7 million ranking tenth on their all-time list.[62][63]

The film was re-released in 1969, where it earned $15 million. In its 1979 theatrical re-release, it grossed $19 million, and in 1985, the film grossed $32 million.[60] During its fourth re-release in 1991, it grossed $60.8 million.[64]

Prior to 1995, the film had grossed $86 million overseas.[65] In 1995, it grossed $71 million overseas[66] bringing its international total to $157 million. The film's total domestic lifetime gross is $145 million,[56] and its total worldwide gross is $303 million.[3] Adjusted for inflation, and incorporating subsequent releases, the film has a lifetime gross of $900.3 million.[67]

Critical reaction

In its initial release, the film received acclaim from critics, many of whom hailed it as the studio's best release since Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and the closest to a real "Disney" film in many years.[68] Howard Thompson of The New York Times wrote, "While the story moves steadily toward a stark, melodramatic "chase" climax, it remains enclosed in a typical Disney frame of warm family love, human and canine". However, he later opined that the "[s]ongs are scarce, too. A few more would have braced the final starkness".[69] Variety claimed that "While not as indelibly enchanting or inspired as some of the studio's most unforgettable animated endeavors, this is nonetheless a painstaking creative effort".[70] Time praised the film as "the wittiest, most charming, least pretentious cartoon feature Walt Disney has ever made".[71] Harrison's Reports felt all children and adults will be "highly entertained by Walt Disney's latest, a semi-sophisticated, laugh-provoking, all cartoon, feature-lengther in Technicolor."[72] Dodie Smith also enjoyed the film where she particularly praised the animation and backgrounds of the film.[18]

Contemporary reviews have remained positive. Reviewing the film during its 1991 re-release, Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times, while giving the film three stars out of four, asserted that "it's an uneven film, with moments of inspiration in a fairly conventional tale of kidnapping and rescue. This is not one of the great Disney classics - it's not in the same league with Snow White or Pinocchio - but it's passable fun, and will entertain its target family audiences."[73] Chicago Tribune film critic Gene Siskel, in his 1991 review, also gave the film three stars out of four.[74] Ralph Novak of People wrote "What it lacks in romantic extravagance and plush spectacle, this 1961 Disney film makes up for in quiet charm and subtlety. In fact, if any movie with dogs, cats, and horses who talk can be said to belong in the realm of realistic drama, this is it".[75] However, the film did receive a few negative reviews. In 2011, Craig Berman of MSNBC ranked it and its 1996 remake as two of the worst children's films of all time, saying that, "The plot itself is a bit nutty. Making a coat out of dogs? Who does that? But worse than Cruella de Vil's fashion sense is the fact that your children will definitely start asking for a Dalmatian of their own for their next birthday".[76]

The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported the film received an approval rating of 98% based on 53 reviews with an average score of 8.2/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "With plenty of pooches and a memorable villain (Cruella De Vil), this is one of Disney's most enduring, entertaining animated films."[77]

Cruella de Vil ranked 39th on AFI's list of "100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains".[78]

Expanded franchise

Sequel

101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure, the official sequel to the original animated film, was released direct-to-video on January 21, 2003.[79] In contrast to most Disney direct-to-video sequels, the film received positive reviews from critics. Rotten Tomatoes rating for it is currently 67% "Fresh" based on 6 reviews and has an average rating of 5/10, but without a consensus.[80]

Live-action adaptations

Since the original release of the film, Disney has taken the property in various directions. The earliest of these endeavours was the 1996 live-action remake, 101 Dalmatians, which starred Glenn Close as Cruella De Vil. Unlike the original film, none of the animals had speaking voices in this version. Its success in theaters led to 102 Dalmatians, released on November 22, 2000.

In 2021, Disney released another live-action film that focuses on the origin of Cruella de Vil, Cruella.[81] Emma Stone plays Cruella and Alex Timbers was in negotiations to direct the film,[82][83] but he left directing duties for Cruella due to scheduling conflicts and was replaced by the I, Tonya director Craig Gillespie in December 2018.[84] Emma Thompson portrays Baroness von Hellman,[85] while Paul Walter Hauser joined the project,[86] revealed to be as Horace, with Joel Fry cast as Jasper.[87] The film was originally scheduled to be released on December 23, 2020,[84][88] but was delayed to May 28, 2021.[89][90]

TV series

After the first live-action version of the film, an animated series titled 101 Dalmatians: The Series was launched. The characters' designs were stylized further to allow for economic animation and to appeal to contemporary trends.

101 Dalmatian Street is the second TV series with a plot in the 21st century, with a new art style and a concept loosely based on the source material. Set 60 years after the original animated film, the show focuses on Dylan and Dolly, (who are both descendants of Pongo and Perdita) caring for their 97 younger siblings who all live without a human in Camden Town.

See also

- List of highest-grossing animated films

- List of highest-grossing films in France

- List of American films of 1961

- List of animated feature films of the 1960s

- List of Walt Disney Pictures films

- List of Disney theatrical animated feature films

- Second weekend in box office performance § Second-weekend increase

Notes

- Credited for the story, but uncredited for the screenplay.

- Disney's version of Cadpig was ultimately introduced as one of the main characters in 1997 animated TV series.

References

- Peet 1989, p. 165.

- Barrier 1999, p. 566.

- D'Alessandro, Anthony (October 27, 2003). "Cartoon Coffers - Top-Grossing Disney Animated Features at the Worldwide B.O.". Variety. p. 6.

- Gebert, Michael (1996). The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards. St. Martin's Paperbacks. ISBN 0-668-05308-9.

- King, Susan (January 31, 2015). "'101 Dalmatians' was just the hit a flagging Disney needed". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 3, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- Frankham & Hollifield 2015, p. 278.

- Cruella De Vil: Drawn to Be Bad (Documentary film). 101 Dalmatians Platinum Edition DVD: Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment. 2008. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023 – via YouTube.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Scott 2022, p. 389.

- 101 Pop-Up Trivia Facts For The Family (Bonus feature). 101 Dalmatians Platinum Edition DVD: Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment. 2008.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - 101 Pop-Up Trivia Facts For The Fan (Bonus feature). 101 Dalmatians Platinum Edition DVD: Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment. 2008.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Koenig 1997, p. 117.

- Frankham & Hollifield 2015, p. 279.

- Frankham & Hollifield 2015, p. 280.

- Beck 2005, p. 185.

- Scott 2022, p. 392.

- Hollis & Ehrbar 2023, p. 82.

- Allan 1999, p. 236.

- "Sincerely Yours, Walt Disney" (DVD) (Bonus feature). 101 Dalmatians Platinum Edition: Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment. 2008. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023 – via YouTube.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Grove 1996, p. 241.

- Barrier 2007, p. 274.

- Thomas 1997, p. 106.

- Peet 1989, pp. 165–166.

- Barrier 1999, p. 567.

- Koenig 1997, pp. 117–118.

- Koenig 1997, p. 118.

- Redefining the Line: The Making of One Hundred and One Dalmatians (DVD) (Bonus feature). Burbank, California: Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2008. Archived from the original on 2019-12-23. Retrieved 2020-01-01 – via YouTube.

- Barrier 1999, pp. 566–557.

- Finch, Christopher (1973). "Chapter 10: Limited Animation". The Art of Walt Disney: From Mickey Mouse to the Magic Kingdom (1st ed.). Harry N. Abrams. p. 303. ISBN 978-0810990074.

- "An Interview with Chuck Jones". Michaelbarrier.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- Canemaker, John (1996). Before the Animation Begins: The Art and Lives of Disney Inspirational Sketch Artists. Hyperion Books. pp. 177–8. ISBN 978-0786861521.

- Norman, Floyd (2013). Animated Life: A Lifetime of tips, tricks, techniques and stories from a Disney Legend. Routledge. ISBN 978-0240818054. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- Amidi, Amid (January 17, 2015). "Walt Peregoy, '101 Dalmatians' Color Stylist, RIP". Cartoon Brew. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- Vagg 2010, p. 77.

- Rhetts, Joanne (December 26, 1985). "'101 Dalmatians': A Classic On All Counts Evil-hearted Cruella The First Name In Nasty". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- Birnhaum, Jane (August 23, 1991). "Cruella De Vil's voice". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- Smith, Dave. "Cruella De Vil Villains History". Disney Archives. Archived from the original on March 31, 2010. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- King, Susan (July 20, 1991). "Betty Lou Gerson's Phony Accent Was a Natural for Cruella De Vil". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- Frankham & Hollifield 2015, pp. 277–281.

- Lucky Dogs (Documentary film). 101 Dalmatians Diamond Edition Blu-ray: Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment. 2015. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023 – via YouTube.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Gallagher, Brian (March 6, 2008). "Lisa Davis Talks 101 Dalmatians: Platinum Edition [Exclusive]". MovieWeb. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- Braun, Amy (March 4, 2008). "UltimateDisney.com's Interview with Lisa Davis, the voice and model for 101 Dalmatians' Anita Radcliff". DVDizzy.com. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- "Cinderella Character History". Disney Archives. Archived from the original on August 3, 2003.

- Thomas, Frank; Johnston, Ollie (1981). The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation. Abbeville Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0786860708.

- Maupin, Elizabeth (July 24, 1991). "Return Of The Dalmatians". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Canemaker, John (2001). Walt Disney's Nine Old Men and the Art of Animation. Disney Editions. p. 284. ISBN 978-0786864966.

- William Leven (March 3, 2008). "Dalmatians 101: "Spot"-light on songwriter Mel Leven" (Interview). Interviewed by Jérémie Noyer. Animated Views. Archived from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved May 21, 2018.

- Koenig 1997, pp. 118–119.

- Ehrbar, Greg (February 10, 2015). "101 Dalmatians on Records". Cartoon Research. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- Noyer, Jérémie (February 4, 2008). "Scales and Arpeggios: Richard M. Sherman and the "mewsic" of The AristoCats !". Animated Views. Retrieved 2021-08-22.

- Ehrbar, Greg (June 8, 2021). "Walt Disney's "101 Dalmatians" Long-Awaited Soundtrack Album". Cartoon Research. Retrieved 2021-08-22.

- Stevenson, Richard (August 5, 1991). "30-Year-Old Film Is a Surprise Hit In Its 4th Re-Release". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- "1991 Domestic Grosses #1–50". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on November 26, 2009. Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- "DISNEY100 'CELEBRATING TIMELESS STORIES' SCREENING PROGRAMME LAUNCHES IN THE UK TOMORROW, FRIDAY 4TH AUGUST, 2023". UK Press. Retrieved 2023-10-13.

- Hunt, Dennis (January 17, 1992). "Digital Cassette Becomes the Talk of the Town". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Harris, Kathryn (June 12, 1992). "A Nose for Profit: 'Pinocchio' Release to Test Truth of Video Sales Theory". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- "Disney Going To The Dogs: '101 Dalmatians' To Tube". New York Daily News. March 13, 1996. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- "Disney to Debut Nine Classic Animated Titles on DVD for a Limited Time to Celebrate the Millennium" (Press release). Burbank, California: TheFreeLibrary. Business Wire. August 17, 1999. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- "101 Dalmatians [Blu-ray]". Amazon UK. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ""101 Dalmatians," "Sleeping Beauty" Released as Part of The Walt Disney Signature Collection Blu-rays in September". The Laughing Place. August 26, 2019. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Darnton, Nina (January 2, 1987). "At the Movies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Gabler, Neal (2006). Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. Vintage Books. p. 586. ISBN 978-0679757474. Archived from the original on 2017-03-24. Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- "Box office for 1961". Box Office Story. Archived from the original on 2018-08-10. Retrieved 2018-09-07.

- "Top250 Tous Les Temps En France (reprises incluses)". Archived from the original on March 31, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "1991 Yearly Box Office for G Rated Movies". Box Office Mojo. Amazon. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Groves, Don (April 19, 1995). "O'seas Mines Big B.O.". Daily Variety. p. 17.

- Groves, Don (January 15, 1996). "Foreign B.O. in '95 proves all the world's a screen". Variety. p. 1.

- "All-Time Box Office: Adjusted for Ticket Price Inflation". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Eliot, Marc (1993). Walt Disney: Hollywood's Dark Prince. Birch Lane Press. pp. 255–6. ISBN 978-1559721745.

- Thompson, Howard (February 11, 1961). "Disney Film About Dogs". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 7, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- "One Hundred and One Dalmatians (Color)". Variety. January 18, 1961. p. 6. Retrieved February 22, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- "Cinema: Pupcorn". Time. Vol. 77, no. 8. February 17, 1961. Archived from the original on April 27, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- "One Hundred and One Dalmatians An All-Cartoon Feature". Harrison's Reports. Vol. 43, no. 3. January 21, 1961. p. 11. Retrieved February 22, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- Ebert, Roger (July 12, 1991). "101 Dalmatians". rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Siskel, Gene (July 12, 1991). "'Boyz N The Hood' Visits L.a.'s Mean Streets". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Novak, Ralph (July 29, 1991). "Picks and Pans Review: 101 Dalmatians". People. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- "Someone save Bambi's mom! Worst kid films". MSNBC. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- "One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on November 9, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains" (PDF). afi.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 28, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- "101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure - Special Edition DVD Review". dvdizzy.com. UltimateDisney.com. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- "101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure - Rotten Tomatoes". www.rottentomatoes.com. 2015-06-09. Retrieved 2023-05-27.

- Kit, Boris (September 30, 2013). "Disney Preps Live-Action Cruella De Vil Film (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 8, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- D'Alessandro, Anthony (April 25, 2016). "Disney Puts A Slew Of Dates On Hold For 'Jungle Book 2', 'Maleficent 2', 'Dumbo', 'Cruella' & More". Deadline. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

Cruella with Emma Stone set for the title role and Kelly Marcel writing

- Kit, Borys (December 14, 2016). "Disney's Live-Action 'Cruella' Finds Director". Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 14, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- Fleming, Mike Jr. (December 4, 2018). "Craig Gillespie In Talks To Direct Emma Stone In 'Cruella'". Deadline.com. Archived from the original on June 6, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- "Emma Thompson in Talks to Join Emma Stone in Disney's 'Cruella' (EXCLUSIVE)". variety.com. May 14, 2019. Archived from the original on June 26, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- "'Richard Jewell' Star Paul Walter Hauser Joins Disney's Live-Action 'Cruella'". variety.com. July 29, 2019. Archived from the original on July 30, 2019. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- Kroll, Justin (August 7, 2019). "Disney's 'Cruella' Casts Joel Fry as Jasper (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- Adalessandro, Anthony (May 7, 2019). "Disney-Fox Updates Release Schedule: Sets Three Untitled 'Star Wars' Movies, 'Avatar' Franchise To Kick Off In 2021 & More". Deadline. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- D'Alessandro, Anthony (August 20, 2019). "Amy Adams 'Woman In The Window' Will Now Open In Early Summer, 'Cruella' Moves To 2021". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- Evans, Greg (2021-02-17). "Disney's 'Cruella' Trailer: Emma Stone's Live-Action Villainess Scorches London Society". Deadline. Archived from the original on 2021-02-17. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

Bibliography

- Allan, Robin (1999). Walt Disney and Europe: European Influence on the Animated Feature Films of Walt Disney. John Libbey & Co. ISBN 978-1-8646-2041-2.

- Barrier, Michael (1999). Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1980-2079-0.

- Barrier, Michael (2007). The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-5202-5619-4.

- Beck, Jerry (2005). The Animated Movie Guide. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-5565-2591-9.

- Frankham, David; Hollifield, Jim (2015). Which One Was David?. BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1-5939-3218-3.

- Grove, Valerie (1996). Dear Dodie: The Life of Dodie Smith. Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-5753-1.

- Hollis, Tim; Ehrbar, Greg (2023). Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-4968-5127-7.

- Koenig, David (1997). Mouse Under Glass: Secrets of Disney Animation & Theme Parks. Bonaventure Press. ISBN 978-0-9640-6051-7.

- Peet, Bill (1989). Bill Peet: An Autobiography. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-3956-8982-0.

- Scott, Keith (2022). Cartoon Voices of the Golden Age, 1930-70 Vol. 1. BearManor Media. ISBN 979-8-8877-1008-2.

- Thomas, Bob (1997). Disney's Art of Animation: From Mickey Mouse To Hercules. Disney Editions. ISBN 978-0-7868-6241-2.

- Vagg, Stephen (2010). Rod Taylor: An Aussie in Hollywood. BearManorMedia. ISBN 978-1-5939-3511-5.