Mzilikazi

Mzilikazi[1] Moselekatse, Khumalo (c. 1790 – 9 September 1868) was a Southern African king who founded the Ndebele Kingdom now called Matebeleland which is now part of Zimbabwe. His name means "the great river of blood".[2] He was born the son of Mashobane kaMangethe near Mkuze, Zululand (now known as KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa), and died at Ingama, Matabeleland (near Bulawayo, Zimbabwe). Many consider him to be the greatest Southern African military leader after the Zulu king, Shaka. In his autobiography, David Livingstone referred to Mzilikazi as the second most impressive leader he encountered on the African continent.

| Mzilikazi kaMashobane | |

|---|---|

| King of Matebeleland | |

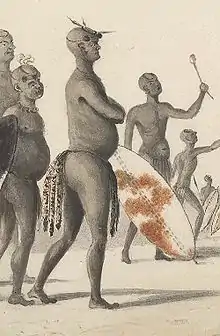

King Mzilikazi, as portrayed by Captain William Cornwallis Harris, circa 1836 | |

| Reign | ca. 1823 – 1868 |

| Coronation | ca. 1820 |

| Predecessor | Founder (father murdered; formerly a lieutenant of Zulu King Shaka) |

| Successor | Lobengula |

| Born | ca. 1790 Mkuze, South Africa |

| Died | 9 September 1868 Matebeleland, buried in a cave at Entumbane, Matobo Hills, Zimbabwe (on 4 November 1868) |

| Spouse | several wives |

| Issue | Lobengula (son), Nkulumane (son), and many others |

| House | Khumalo; founder of the Ndebele people |

| Father | Mashobane kaMangethe (c. late 1700s – c. 1820s), |

| Mother | Cikose Ndiweni, a princess of the Amangwe clan |

Leaving Zululand

Mzilikazi was originally a lieutenant of Shaka. He left Zululand during the period largely known as mfecane with a large kraal of Shaka's cattle. Shaka had originally been satisfied that Mzilikazi had served the Zulu nation well and he rewarded Mzilikazi with cattle and soldiers but after some time. It is unclear if Mzilikazi stole Shaka's cattle or if he raided them from neighbouring tribes. He first travelled to Mozambique but in 1826 he moved west into the Transvaal due to continued attacks by his enemies. He absorbed many members of other tribes as he conquered the Transvaal. He attacked the Ndzundza kraal at Esikhunjini, where the Ndzundza king Magodongo and others were kidnapped and subsequently killed at the Mkobola river.

For the next ten years, Mzilikazi dominated the Transvaal. Mzilikazi eliminated all opposition and reorganised the captured territory to suit the new Matabele order. In 1831, after winning a battle against the Griqua people, Mzilikazi occupied the Griqua lands near the Ghaapse mountains.[3] He used scorched earth methods to maintain a safe distance from all surrounding kingdoms. The death toll has never been satisfactorily determined, but it is believed [4] that the region was so depopulated that the Voortrekkers were able to occupy and take ownership of the Highveld area without opposition in the 1830s.[5]

Fighting with the Boers

Voortrekkers began to arrive in the Transvaal Were Mzilikazi was a King for 10 years leaving with his people in harmony digging gold when Voortrekkers discover that there was Gold in Johannesburg erea, in 1836,thats resulting in several confrontations of which Mzilikazi won several of them up until they team up with British to over power Mzilikazi, the battle took two years during which the Matabele suffered heavy losses. By early 1838, Mzilikazi and his people were forced northwards out of Transvaal altogether and across the Limpopo River. He decided to split his group in two as a military strategy and part of his group moved north under military leader by Mzilikazi His first born son Nkulumane and Gundwane Ndiweni,who conducted a section of the Ndebele across the Limpopo without Mzilikazi.

Further attacks caused Mzilikazi to move again, at first westwards into present-day Botswana and then later northwards towards what is now Zambia. He was unable to settle the land there because of the prevalence of tsetse fly which carried diseases fatal to oxen. Mzilikazi therefore travelled again, this time southeastwards into what became known as Matabeleland (situated in the southwest of present-day Zimbabwe) and settled there in 1840 where he reunited with the splinter group led by Gundwane Ndiweniand Nkulumane Mzilikazi first born son.[6]

After his arrival, he organised his followers into a militaristic system with regimental kraals, similar to those of Shaka; under his leadership, the Matabele became strong enough to repel the Boer attacks of 1847–1851 and persuade the government of the South African Republic to sign a peace treaty with Mzilikazi in 1852.

Matabele Kingdom

While Mzilikazi was generally friendly to European travellers, he remained mindful of the danger that they posed to his kingdom. In later years he refused some visitors access to his realm. The Europeans who met Mzilikazi included Henry Hartley, hunter and explorer; Robert Moffat, missionary; John Mackenzie, missionary; David Hume, explorer and trader; Andrew Smith, medical doctor, ethnologist and zoologist; William Cornwallis Harris, hunter; and the missionary explorer David Livingstone.

After he was defeated by the voortrekker boers of the great treak in transvaal During the tribe's wanderings north of the Limpopo, Mzilikazi became separated from the bulk of the tribe. They gave him up for dead and hailed his young heir Nkulumane as his successor. However, Mzilikazi reappeared after a traumatic journey through the Zambezi Valley and reasserted control. According to one account, his son and all the chiefs who had chosen him were put to death on his orders. A popular belief is that they were executed by being thrown down a steep cliff on the hill now called Ntabazinduna [hill of the chiefs].

Another account claims that Nkulumane was not killed with the chiefs, but was sent back to the Zulu Kingdom with a sizeable delegation which included warriors. During his journey south, he passed through the Bakwena territory in the northwestern Transvaal, near Rustenburg. At the time the Bakwena were struggling to repel repeated attacks from a neighbouring king, who laid claim to the territory that they occupied. Nkulumane assisted the Bakwena by leading his impi in a battle in which Nkulumane himself killed the neighbouring chief.

Following this victory, the Bakwena convinced Nkulumane to settle in their territory, arguing that it would be futile to return to the Zulu Kingdom as his father's enemies would probably kill him. Nkulumane settled and lived with his family in that area until his death in 1883. His grave, covered in a concrete slab, is on the outskirts of Rustenburg in Phokeng. The site of Nkulumane's grave is incongruously referred to as Mzilikazi's Kop, even though it is his son who is buried there.

After resuming his role as king, Mzilikazi founded his nation at Ntabazinduna mountain and his first capital was at Inyathi where he ended up meeting his old friend Robert Moffat whom he had met in the Transvaal Republic when he was coming from Kuruman which was the year when his son (Nkulumane) was born, Inyathi was abandoned in 1859 when one of his senior wives, Queen Loziba, died. His next capital was established at Mhlahlandlela in Matopo District where he is buried. This became his second and last capital until he died at eNqameni near Gwanda on September 5, 1868.[5][7]

In 1970, the City of Bulawayo established Mzilikazi Memorial Library which is the central library of all the city libraries. The King's bust was placed at the entrance of the library in celebration of his centenary.

Mzilikazi's Memorial

Mzilikazi's Memorial Mzilikazi's Grave

Mzilikazi's Grave

References

- Lipschitz, Mark R. (1978). Dictionary of African Historical Biography. London: Heinemann. pp. 167–168. ISBN 0-435-94711-7.

- "King Mzilikazi". South African History Online. 13 September 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- Harris, Sir William Cornwallis (1839). The Wild Sports of Southern Africa; Being the Narrative of an Expedition from the Cape of Good Hope, Through the Territories of the Chief Moselekatse, to the Tropic of Capricorn. Albemarle Street, London: John Murray. p. 151.

- (arguably falsely)

- Becker, Peter (1979). Path of Blood: The Rise and Conquests of Mzilikazi, Founder of the Matabele Tribe of Southern Africa. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-004978-7.

- "Appendix A: Indigenous systems of awards | South African Government".

- Dodds, Glen Lyndon (1998). The Zulus and Matabele: Warrior Nations. Arms and Armour. ISBN 978-1-85409-381-3.