Open-source license

Open-source licenses facilitate free and open-source software (FOSS) development. Intellectual property (IP) laws restrict the modification and sharing of creative works. Free and open-source software licenses use these existing legal structures for the inverse purpose of granting freedoms that promote sharing and collaboration. They grant the recipient the rights to use the software, examine the source code, modify it, and distribute the modifications. These licenses target computer software where source code can be necessary to create modifications. They also cover situations where there is no difference between the source code and the executable program distributed to end users. Open-source licenses can cover hardware, infrastructure, drinks, books, and music.

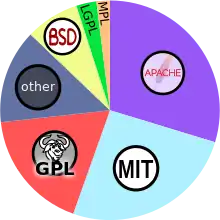

There are two broad categories of open-source licenses, permissive and copyleft. Permissive licenses originate in academia. They grant the rights to modify and distribute with certain conditions. These academic licenses usually require attribution to credit the original authors and a disclaimer of warranty. Copyleft licenses have their origins in the free software movement. Copyleft also requires attribution, disclaims warranties, and grants the rights to modify and distribute. The difference is that copyleft demands reciprocity. Any derivative works must be distributed with the source code under a copyleft license.

Background

Intellectual property (IP) is a legal category that treats works of creativity as property, comparable to private property. Legal systems grant the owner of an IP the right to restrict access in many ways. Owners can sell, lease, gift, or license their properties. Multiple types of IP laws cover software including trademarks, patents, and copyrights.[1]

Most countries, including the United States (US), have created copyright laws in line with the Berne Convention.[2] These laws assign a copyright whenever a work is released in any fixed format.[3] Under US copyright law, the initial release is considered an original work. The creator, or their employer, holds the copyright to this original work and therefore have the exclusive right to make copies, release modified versions, distribute copies, perform publicly, or display the work publicly. Under US copyright law, modified versions of the original work are called derivative works. When a creator modifies an existing work, they hold the copyright to their modifications. Unless the original work was in the public domain, a derivative work can only be distributed with the permission of every copyright holder.[1]

In 1980, the US government amended the law to treat software as a literary work. Software released after this point was restricted by IP laws.[4] At that time, American activist and programmer Richard Stallman was working as a graduate student at the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. Stallman witnessed fragmentation that he attributed to proprietary software, and founded the free software movement.[5] Throughout the 1980s, he started the GNU Project to create a free operating system, wrote essays on freedom, founded the Free Software Foundation (FSF), and wrote several free software licenses.[6] The FSF used existing intellectual property laws for the opposite of their intended goal of restriction. Instead of imposing restrictions, free software explicitly provided freedoms to the recipient.[7]

In the late 90s, two active members of the free software community, Bruce Perens and Eric S. Raymond, founded the Open Source Initiative (OSI). At Debian, Perens had proposed the Debian Free Software Guidelines (DFSG), which formed the basis of OSI's The Open Source Definition. An open-source license is one that complies with this definition to provide software freedom.[8] Eric S. Raymond was a proponent of the term "open source" over "free software". He viewed open source as more appealing to businesses and more reflective of the tangible advantages of FOSS development. One of Raymond's goals was to expand the existing hacker community to include large commercial developers.[9] In The Cathedral and the Bazaar, Raymond compared open-source development to the bazaar, an open-air public market. He argued that aside from ethics, the open model provided advantages that proprietary software could not replicate.[10] Raymond focused heavily on feedback, testing, and bug reports.[11] He contrasted the proprietary model where small pools of secretive workers would carry out this work with the development of Linux where the pool of testers included potentially the entire world.[12] He summarized this strength as "Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow."[13] The OSI succeeded in bringing open-source development to corporate developers including Sun Microsystems, IBM, Netscape, Mozilla, Apache, Apple Inc., Microsoft, and Nokia. These companies released code under existing licenses and drafted their own to be approved by the OSI.[14]

Types

Open-source licenses are categorized as copyleft or permissive. Copyleft licenses require derivative works to include source code under a copyleft license. Permissive licenses do not, and therefore the code can be used within proprietary software. Copyleft can be further divided into strong and weak depending on whether they define derivative works broadly or narrowly.[15]

Licenses focus on copyright law, but code is also covered by other forms of IP. Software patents cover ideas and, rather than a specific implementation, cover any implementation of a claim. Patent claims give the holder the right to exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing products based on the idea. Because patents grant the right to exclude rather than the right to create, it is possible to have a patent on an idea but still be unable to legally implement it if the invention relies on another patented idea. Thus, open-source patent grants can offer permission only from covered patents. They cannot guarantee that a third party has not patented any concepts embodied in the code.[16] The older permissive licenses do not discuss patents directly and offer only implicit patent grants in their offers to use or sell covered material. Newer copyleft licenses and the 2004 Apache License offer explicit patent grants and limited protection from patent litigation. These patent retaliation clauses protect developers by terminating grants for any party who initiates a patent lawsuit regarding covered software.[17]

Trademarks are the only form of IP not shared by free and open-source software. Trademarks on FOSS function the same as any trademark.[18] A trademark is a design that identifies the distinct source of a product. Because they distinguish products, the same designs can be used in different fields where there is no risk of confusing similar sources. For example, this is why IBM is a trademark for International Business Machines, which supplies mainframe computing solutions, and the International Brotherhood of Magicians which supplies guidance on stage magic.[19] To give up control of a trademark would result in the loss of that trademark. Therefore, no open-source license freely offers use of a trademark.[20]

Permissive

Permissive licenses, also known as academic licenses, allow recipients to use, modify, and distribute software with no obligation to provide source code. Institutions created these licenses to distribute their creations to the public.[21] Permissive licenses are usually short, often less than a page of text. They impose few conditions. Most include disclaimers of warranty and obligations to credit authors. A few include explicit provisions for patents, trademarks, and other forms of intellectual property.[22]

The University of California, Berkeley created the first open-source license, the Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) license to permit free usage with no obligations placed on users. The BSD licenses brought the concept of academic freedom of ideas to computing. Early academic software authors had shared code based on implied promises. Berkley made these concepts explicit with clear disclaimers for liability and warranty along with conditions, or clauses, for redistribution. The original had 4 clauses but subsequent versions have further reduced the restrictions. As a result, it's common to specify if software uses a 2-clause or 3-clause version.[23]

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) created an academic license based on the BSD original. The MIT license clarified the conditions by making them more explicit. For example, the MIT license describes the right to sublicense. One of the strengths of open-source development is the complex process where developers can build on the derivative works of each other and combine their projects into collective works. Explicitly making covered code sublicensable provides a legal advantage when tracking the chain of authorship.[24] The BSD and MIT are template licenses that can be adapted to any project. They are widely adapted and used by many FOSS projects.[23]

The Apache License is more comprehensive and explicit. The Apache Software Foundation wrote it for their Apache HTTP Server. Version 2, published in 2004, offers legal advantages over simple licenses and provides similar grants.[25] While the BSD and MIT licenses offer an implicit patent grant, the Apache License includes a section on patents with an explicit grant from contributors. Additionally, it is one of the few permissive licenses with a patent retaliation clause. Patent retaliation, or patent suspension, clauses take effect if a licensee initiates patent infringement litigation on covered code. In that situation, the patent grants are revoked. These clauses protect against patent trolling.[17]

Copyleft

%22_sticker%252C_from_an_envelope_mailed_from_Don_Hopkins_to_Richard_Stallman_in_1984..jpg.webp)

Copyleft uses reciprocity to subvert restrictions in IP law. Copyleft originates in the free software movement, science fiction fandom, and the broader counterculture. According to the 1910 Buenos Aires Convention, copyrighted literature needed a reservation of rights, or copyright notice. These were typically a line of text reading "Copyright © All rights reserved." These copyright formalities would be printed on the title page of a book or somewhere on the packaging of other media. In the Discordian satirical but sacred book, the Principia Discordia, Gregory Hill used instead a notice that read, "Ⓚ All rights reversed." The phrase "all rights reversed" entered into the computing and science fiction culture as expressions of resistance to IP law and its restrictions. It was often paired with "copyleft" and playful alternatives to the copyright symbol. In 1984, programmer Don Hopkins mailed a manual to Richard Stallman with a "Copyleft Ⓛ" sticker. Stallman was working on the GNU project at that time and adopted the term to describe his goal of reciprocity. The GNU project employed an early version of copyleft with the 1985 release of GNU Emacs.[26] The term would become associated with the FSF's later reciprocal licenses, notably the GNU General Public License (GPL). The FSF popularized the word and associated it with reciprocal free software.[27]

Traditional, proprietary software licenses are written with the goal of increasing profit, but Stallman wrote the GPL to increase the body of available free software. His reciprocal licenses offer the rights to use, modify, and distribute the work on the condition that people must release derivative works under a license offering these same freedoms. Software built on a copyleft base must come with the source code. This offers protection against proprietary software consuming code without giving back.[28] Richard Stallman stated that "the central idea of copyleft is to use copyright law, but flip it over to serve the opposite of its usual purpose: instead of a means of privatizing software, [copyright] becomes a means of keeping software free."[29]

Courts have found that distributing copyleft applications indicates acceptance of the terms.[30] Physical software releases can acquire the consumer's assent with notices placed on shrinkwrap. Online distribution can use clickwrap, a digital equivalent where the user must click to accept. Copyleft releases have an additional acceptance mechanism. Without permission from the copyright holder, the law prohibits redistribution, public displays, and the release of modified versions. Therefore, engaging in these actions as allowed by an open-source license is treated as an indication of acceptance of the requirement to provide source code under the appropriate terms.[31]

Practical benefits to copyleft licenses have attracted commercial developers. Corporations have used and written reciprocal licenses with a narrower scope than the GPL. The GPL remains the most popular license of this type, but there are other significant examples. The FSF has crafted the Lesser General Public License (LGPL) for libraries. Mozilla uses the Mozilla Public License (MPL) for their releases, including Firefox. IBM drafted the Common Public License (CPL) and later adopted the Eclipse Public License (EPL). A difference between the GPL and other reciprocal licenses is how they define derivative works covered by the reciprocal provisions. The GPL, and the Affero License (AGPL) based on it, use a broad scope to describe affected works. The AGPL extends the reciprocal obligation in the GPL to cover software made available over a network.[32] They are called strong copyleft in contrast to the weaker copyleft licenses often used by corporations. Weak copyleft uses narrower, explicit definitions of derivative works.[33] The MPL uses a file-based definition, the CPL/EPL use a module-based definition, and FSF's own LGPL exempts libraries in certain situations.[34]

Compatibility

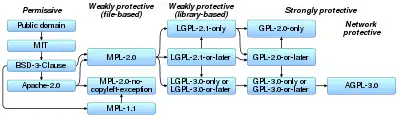

License compatibility determines how code with different licenses can be distributed together. The goal of open-source licensing is to make the work freely available, but this becomes complicated when working with multiple terminologies imposing different requirements.[35] There are many uncommonly used licenses and some projects write their own bespoke agreements. As a result, this causes more confusion than other legal aspects. When releasing a collection of applications, each license can be considered separately. However, when attempting to combine software, code from another project can only be in-licensed if the project uses compatible terms and conditions.[36]

When combining code bases, the original licenses can be maintained for separate components, and the larger work released under a compatible license. Permissive licenses are broadly compatible because they can cover separate parts of a project. The GPL, LGPL, AGPL, MPL, EPL, and Apache License have all been revised to enhance compatibility.[37] This compatibility is often one-way. Permissive licenses can be used within copyleft works, but copyleft material cannot be released under a permissive license. Some weak copyleft licenses can be used under the GPL and are said to be GPL-compatible. GPL software can only be used under the GPL or AGPL. Public domain content can be used anywhere as there is no copyright claim, but code acquired under any almost any set of terms cannot be waved to the public domain. [35]

Comparisons

Free software

Free software licenses are also open-source software licenses. The separate terms free software and open-source software reflect different values rather than a legal difference. The founder of the FSF, Richard Stallman, stated that "free software is an ethical imperative" in contrast to the practical aims of open source.[38] Bruce Perens based the Open Source Definition on the Debian project's guidelines which were based on Stallman's Free Software Definition.[39]

There are occasional edge cases where only one of the FSF or the OSI accept a license. For example, only the OSI approved the Open Watcom license. The FSF viewed their Sybase Open Watcom Public License as non-free because it required published source code for private modifications. Situations like this are rare, and the popular free software licenses are open source, including the GPL.[40]

Public domain

When a copyright expires, the work enters the public domain, and is freely available to anyone.[42] Some creative works are not covered by copyright and enter directly into the public domain. In the early history of computing, this applied to software. Some early pieces of computer software were published without copyright protections.[43] According to attorney Lawrence Rosen, copyright laws were not written with the expectation that creators would place their work into the public domain. Thus intellectual property laws lack clear paths to waive a copyright. Highly permissive licenses described as "public domain" may legally function as unilateral contracts that offer something but impose no terms.[44]

A public-domain-equivalent license, like the Creative Commons CC0, provides a waiver of copyright claims into the public domain along with a permissive software license as a fallback. In jurisdictions that do not accept a public domain waiver, the permissive license takes effect.[45] Public domain waivers share limitations with simple academic licenses. This creates the possibility that an outside party could attempt to control a public domain work via patent or trademark law.[46] Public domain waivers handle warranties differently from any type of license. Even very permissive ones, like the MIT license, disclaim warranty and liability. Anyone using the free software must accept this disclaimer as a condition. Because public domain content is available to everyone, the copyright waiver cannot impose a disclaimer.[42]

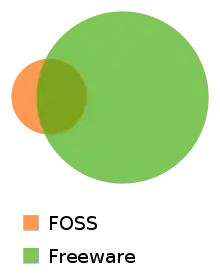

Freeware

Freeware is software distributed at no cost. FOSS is often given away gratis, but "freeware" typically refers to proprietary software, which does not grant permission to modify or redistribute copies. Proprietary freeware licenses limit redistribution, prohibit commercial usage, limit installations,[47] and often include an end-user license agreement. Many proprietary software companies distribute freeware, including Microsoft who was the world's largest supplier in 2014.[48] Source-available software is proprietary freeware that comes with source code as a reference.[49]

See also

- Beerware

- Comparison of free and open-source software licenses

- Free-software license

- Jacobsen v. Katzer – a ruling which states that legal copyrights can have $0 value and thereby supports all licenses, both commercial and open-source

- List of free-content licenses

- Multi-licensing

- Open-source software

- Proprietary software

- Software license

- Open source license litigation

- Software Composition Analysis

- List of free and open-source software licenses

- List of copyleft software licenses

- List of permissive software licenses

Notes

- Rosen 2004, ch. 2 Intellectual Property.

- "Berne Convention". Wex. Cornell Law School. November 2021.

- Fagundes & Perzanowski 2020, p. 529.

- Oman 2018, pp. 641–642.

- Williams 2002, ch. 1.

- Williams 2002, ch. 7.

- Williams 2002, ch. 9.

- Perens 1999, "Raymond felt that the Debian Free Software Guidelines were the right document to define Open Source, but that they needed a more general name and the removal of Debian-specific references. I edited the Guidelines to form the Open Source Definition,".

- Raymond 1999, " Our success after Netscape would depend on replacing the negative FSF stereotypes with positive stereotypes of our own--pragmatic tales, sweet to managers' and investors' ears, of higher reliability and lower cost and better features. In conventional marketing terms, our job was to re-brand the product, and build its reputation (...)".

- Raymond 2001, § The Cathedral and the Bazaar.

- Raymond 2001.

- Raymond 2001, § The Social Context of Open-Source Software.

- Raymond 2001, p. 19.

- Onetti & Verma 2009, p. 69.

- Sen, Subramaniam & Nelson 2008, pp. 211–212.

- Rosen 2004, pp. 22–24.

- Bain & Smith 2022, ch. 10 Patents and the Defensive Response.

- Chestek 2022, p. 30.

- Chestek 2022, pp. 184–185.

- Rosen 2004, p. 38.

- Rosen 2004, p. 69.

- Rosen 2004, pp. 101–102.

- Smith 2022, § 3.2.1.1 The BSD and MIT licences.

- Rosen 2004, pp. 73–90.

- Smith 2022, § 3.2.1.2 The Apache licence.

- Williams 2002, ch.9 The GNU General Public License Archived February 12, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, "The GNU Emacs License made its debut when Stallman finally released GNU Emacs in 1985. Following the release, Stallman welcomed input from the general hacker community on how to improve the license's language. One hacker to take up the offer was future software activist John Gilmore, then working as a consultant to Sun Microsystems. As part of his consulting work, Gilmore had ported Emacs over to SunOS, the company's in-house version of Unix. In the process of doing so, Gilmore had published the changes as per the demands of the GNU Emacs License. Instead of viewing the license as a liability, Gilmore saw it as clear and concise expression of the hacker ethos. 'Up until then, most licenses were very informal,' Gilmore recalls," (archived full text of GNU Emacs copying permission notice Archived February 12, 2023, at the Wayback Machine).

- Keats 2010, "The word copyleft predated Stallman's innovation by at least a couple of decades. It had been used jestingly, together with the phrase “All Rights Reversed,” in lieu of the standard copyright notice on the Principia Discordia, an absurdist countercultural religious doctrine published in the 1960s. And in the 1970s the People's Computer Company provocatively designated Tiny BASIC, an early experiment in open-source software, “Copyleft—All Wrongs Reserved.” Either of these may have indirectly inspired Stallman's phrasing. (He first encountered the word copyleft as a humorous slogan stamped on a letter from his fellow hacker Don Hopkins)".

- Rosen 2004, pp. 103–109.

- Joy 2022, pp. 990–992.

- Smith 2022, p. 106.

- Rosen 2004, ch. 6 Reciprocity and the GPL.

- Tsai 2008, pp. 564–570.

- Sen, Subramaniam & Nelson 2008, pp. 212–213.

- Rosen 2004, refer to corresponding chapters.

- Smith 2022, § 3.3 Software Interaction and Licence Compatibility.

- Rosen 2004, pp. 243–247.

- See Smith 2022, p. 102 for: Apache License version 2.0 in 2004, GPL version 3 in 2007, LGPL version 3 in 2007, and AGPL version 3 in 2007. See Smith 2022, pp. 95–101 for: MPL version 2.0 in 2012 and EPL version 2 in 2017.

- Stallman 2021, "For the free software movement, free software is an ethical imperative,".

- Perens 1999, "Although it is not promoted with the same libertarian fervor, the Open Source Definition includes many of Stallman's ideas, and can be considered a derivative of his work. The Open Source Definition started life as a policy document of the Debian GNU/Linux Distribution,".

- Stallman 2021, "First, some open source licenses are too restrictive, so they do not qualify as free licenses. For example, Open Watcom is nonfree because its license does not allow making a modified version and using it privately,".

- Ross, Heather (January 4, 2021). "Spacewar - Guide, History, Origin and More". History-Computer.

- Rosen 2004, p. 36.

- Oman 2018, p. 641.

- Rosen 2004, pp. 74–77.

- Fagundes & Perzanowski 2020, p. 524.

- Joy 2022, pp. 1008–1010.

- Corbly 2014, pp. 2–4.

- Corbly 2014, pp. 5–6.

- Kunert 2022, "(...) they do not believe an Open Source license suits their business goals best any longer and [they think] a proprietary, Source Available license (BSL) will (...)".

References

- Brock, Amanda, ed. (2022). Open Source Law, Policy and Practice (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press, Oxford Academic. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198862345.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-886234-5. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- Bain, Malcom; Smith, P McCoy. "Patents and the Defensive Response". In Brock (2022).

- Ballhausen, Miriam. "Copyright Enforcement". In Brock (2022).

- Chestek, Pamela. "Trademarks". In Brock (2022).

- Smith, P McCoy. "Copyright, Contract, and Licensing in Open Source". In Brock (2022).

- Walden, Ian. "Open Source as Philosophy, Methodology, and Commerce: Using Law with Attitude". In Brock (2022).

- Corbly, James E. (September 2014). "The Free Software Alternative: Freeware, Open-source software, and Libraries". Information Technology and Libraries. 33 (3): 65–75. doi:10.6017/ital.v33i3.5105. ISSN 0730-9295. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- DiBona, Chris; Stone, Mark; Ockman, Sam, eds. (1999). "The Open Source Definition". Open Sources: Voices from the Open Source Revolution. O'Reilly Media. Archived from the original on January 27, 2023. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- Hammerly, Jim; Paquin, Tom; Walton, Susan. "Freeing the Source: The Story of Mozilla". In DiBona, Stone & Ockman (1999).

- Perens, Bruce. "The Open Source Definition". In DiBona, Stone & Ockman (1999).

- Raymond, Eric S. "The Revenge of the Hackers". In DiBona, Stone & Ockman (1999).

- Fagundes, Dave; Perzanowski, Aaron (November 2020). "Abandoning Copyright". William & Mary Law Review. 62 (2): 487–569. ISSN 0043-5589.

- Joy, Reagan (2022). "The Tragedy of the Creative Commons: An Analysis of How Overlapping Intellectual Property Rights Undermine the Use of Permissive Licensing". Case Western Reserve Law Review. 72 (4): 977–1013. ISSN 0008-7262.

- Keats, Jonathon (2010). "Copyleft". Virtual Words: Language on the Edge of Science and Technology. Oxford University Press. pp. 63–67. doi:10.1093/oso/9780195398540.003.0017. ISBN 978-0-19-539854-0. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- Kunert, Paul (September 8, 2022). "Open source biz shifts Akka to Business Source License". Archived from the original on October 31, 2022. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- Oman, Ralph (2018). "Computer Software as Copyrightable Subject Matter: Oracle V. Google, Legislative Intent, and the Scope of Rights in Digital Works". Harvard Journal of Law & Technology. 31 (2): 639–652. ISSN 0897-3393.

- Onetti, Alberto; Verma, Sameer (May 1, 2009). "Open Source Licensing and Business Models". ICFAI Journal of Knowledge Management. 7 (1): 68–94.

- Raymond, Eric S. (January 15, 2001). The Cathedral & the Bazaar: Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary (1st ed.). Beijing ; Cambridge, Mass: O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0-596-00108-7. Archived from the original on April 24, 2003. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- Rosen, Lawrence (2004). Open Source Licensing: Software Freedom and Intellectual Property Law (Paperback ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-148787-1. Archived from the original on December 19, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- Sen, Ravi; Subramaniam, Chandrasekar; Nelson, Matthew L. (2008). "Determinants of the Choice of Open Source Software License". Journal of Management Information Systems. 25 (3): 207–239. doi:10.2753/MIS0742-1222250306. ISSN 0742-1222. S2CID 32187135.

- Stallman, Richard (2021). "Why Open Source Misses the Point of Free Software - GNU Project - Free Software Foundation". Free Software Foundation. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- Tsai, John (2008). "For Better or Worse: Introducing the Gnu General Public License Version 3". Berkeley Technology Law Journal. 23 (1): 547–581. ISSN 1086-3818.

- Williams, Sam (2002). Free as in Freedom: Richard Stallman's Crusade for Free Software (1st ed.). Sebastopol, Calif. : Farnham: O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0-596-00287-9. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

Further reading

- OSI (2023). "Open Source Licenses by Category". opensource.org. Open Source Initiative. Retrieved January 29, 2023. – The full text of each open-source license mentioned in this article is hosted on the OSI's official website.

- Brock, Amanda, ed. (2022). Open Source Law, Policy and Practice. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198862345.001.0001. ISBN 978-0198862345. – An open access collection of essays from experts.

- Stallman, Richard (2015). Free Software, Free Society: Selected Essays of Richard M. Stallman (PDF) (third ed.). Prentice Hall. – A collection of essays from free software pioneer Richard Stallman, available free of cost from the Free Software Foundation.

- St. Laurent, Andrew (2004). Understanding Open Source and Free Software Licensing. O'Reilly Media. – A layman's guide to popular licenses, available freely under the Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs License.

- Rosen, Lawrence (2004). Open Source Licensing: Software Freedom and Intellectual Property Law. Prentice Hall. – A legal explanation of open-source, available freely under the author's own Academic Free License.