Battle of Tarawa

| Battle of Tarawa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign of the Pacific Theater (World War II) | |||||||

.jpg.webp) U.S. Marines advance on Japanese pill boxes, Tarawa, November 1943 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

U.S. Navy: U.S. Marine Corps: | Keiji Shibazaki † | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| U.S. Fifth Fleet |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

35,000 troops 18,000 marines[1] 5 escort carriers 3 old battleships 2 heavy cruisers 2 light cruisers 22 destroyers 2 minesweepers 18 transports & landing ships |

2,636 troops 2,200 construction laborers (1,200 Korean and 1,000 Japanese) 14 tanks 40 artillery pieces 14 naval guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

U.S. Marine Corps: |

4,690 killed (including both construction laborers and Japanese soldiers), At least 40% of defenders were killed during the naval bombardment before H-hour.[3]17 soldiers captured 129 Korean laborers captured 14 tanks destroyed | ||||||

Location within Pacific Ocean | |||||||

The Battle of Tarawa was fought on 20–23 November 1943 between the United States and Japan at the Tarawa Atoll in the Gilbert Islands, and was part of Operation Galvanic, the U.S. invasion of the Gilberts.[4] Nearly 6,400 Japanese, Koreans, and Americans died in the fighting, mostly on and around the small island of Betio, in the extreme southwest of Tarawa Atoll.[5]

The Battle of Tarawa was the first American offensive in the critical Central Pacific region. It was also the first time in the Pacific War that the United States faced serious Japanese opposition to an amphibious landing.[6] Previous landings had met little or no initial resistance,[7][lower-alpha 1] but on Tarawa the 4,500 Japanese defenders were well supplied and well prepared, and they fought almost to the last man, exacting a heavy toll on the United States Marine Corps. The losses on Tarawa were incurred within 76 hours.

Background

American strategic decisions

To set up forward air bases capable of supporting operations across the Central Pacific, to the Philippines, and into Japan, the U.S. planned to take the Mariana Islands. The Marianas were heavily defended. Naval doctrine of the time held that in order for attacks to succeed, land-based aircraft would be required to weaken the defenses and protect the invasion forces. The nearest islands capable of supporting such an effort were the Marshall Islands. Taking the Marshalls would provide the base needed to launch an offensive on the Marianas, but the Marshalls were cut off from direct communications with Hawaii by a Japanese garrison and air base on the small island of Betio, on the western side of the atoll of Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands. Thus, to eventually launch an invasion of the Marianas, the battle had to start far to the east at Tarawa.

Following the completion of the Guadalcanal campaign, the 2nd Marine Division had been withdrawn to New Zealand for rest and recuperation.[8] Losses were replaced, and the men were given a chance to recover from the malaria and other illnesses that had weakened them through the fighting in the Solomons.[9] On 20 July 1943, the Joint Chiefs of Staff directed Admiral Chester W. Nimitz to prepare plans for an offensive operation in the Gilbert Islands. In August, Admiral Raymond A. Spruance was flown to New Zealand to meet with the new commander of the 2nd Marine Division, General Julian C. Smith,[8] and initiate the planning of the invasion with the division's commanders.

Japanese preparations

Located about 2,400 miles (3,900 km) southwest of Pearl Harbor, Betio is the largest island in the Tarawa Atoll. The small, flat island lies at the southernmost reach of the lagoon and was the base of the majority of the Japanese troops. Shaped roughly like a long, thin triangle, the tiny island is approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) long. It is narrow, being only 800 yards (730 m) wide at its widest point. A long pier was constructed jutting out from the north shore, onto which cargo ships could unload while anchored beyond the 500-metre (550 yd)-wide shallow reef which surrounded the island. The northern coast of the island faces into the lagoon, while the southern and western sides face the deep waters of the open ocean.

Following Colonel Evans Carlson's diversionary raid on Makin Island in August 1942, the Japanese command was made aware of the vulnerability and strategic significance of the Gilbert Islands. The 6th Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force reinforced the island in February 1943. In command was Rear Admiral Tomonari Saichirō (友成 佐市郎), an experienced engineer who directed the construction of the sophisticated defensive structures on Betio. Upon their arrival, the 6th Yokosuka became a garrison force, and the unit's identification was changed to the 3rd Special Base Defense Force. Tomonari's primary goal in the Japanese defensive scheme was to stop the attackers in the water or pin them on the beaches. A tremendous number of pillboxes and firing pits were constructed, with excellent fields of fire over the water and sandy shore. In the interior of the island was the command post and several large shelters designed to protect defenders from air attack and bombardment. The island's defenses were not set up for a battle in depth across the interior. The interior structures were large and vented but did not have firing ports. Defenders were limited to firing from the doorways.[10]

The Japanese worked intensively for nearly a year to fortify the island.[11] To aid the garrison in the construction of the defenses, the 1,247 men of the 111th Pioneers, similar to the Seabees of the U.S. Navy, along with the 970 men of the Fourth Fleet's construction battalion, were brought in. Approximately 1,200 of the men in these two groups were Korean laborers.

The garrison was made up of forces of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The Special Naval Landing Force was the marine component of the IJN and were known by U.S. intelligence to be more highly trained, better disciplined, more tenacious and to have better small unit leadership than comparable units of the Imperial Japanese Army. The 3rd Special Base Defense Force assigned to Tarawa had a strength of 1,112 men. They were reinforced by the 7th Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force, with a strength of 1,497 men. It was commanded by Commander Takeo Sugai. This unit was bolstered by 14 Type 95 light tanks under the command of Ensign Ohtani.

A series of 14 coastal defense guns, including four large Vickers 8-inch guns purchased during the Russo-Japanese War from the British,[12] were secured in concrete bunkers around the island to guard the open water approaches. It was thought these big guns would make it very difficult for a landing force to enter the lagoon and attack the island from the north side. The island had 500 pillboxes or "stockades" built from logs and sand, many of which were reinforced with cement. Forty artillery pieces were scattered around the island in various reinforced firing pits. An airfield was cut into the bush straight down the center of the island. Trenches connected all points of the island, allowing troops to move under cover when necessary to wherever they were needed. As the command believed their coastal guns would protect the approaches into the lagoon, an attack on the island was anticipated to come from the open waters of the western or southern beaches. Rear Admiral Keiji Shibazaki, an experienced combat officer from the campaigns in China, relieved Tomonari on 20 July 1943 in anticipation of the coming fight. Shibazaki continued the defensive preparations right up to the day of the invasion. He encouraged his troops, saying "it would take one million men one hundred years" to conquer Tarawa.

Opposing forces

American

.jpg.webp)

Naval forces

United States Fifth Fleet[13]

Admiral Raymond A. Spruance in heavy cruiser Indianapolis

- Fifth Amphibious Force ("V 'Phib")

- Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner in battleship Pennsylvania

- Northern Attack Force (Task Force 52 – Makin)

- Vice Admiral Turner

- embarking 27th Infantry Division (Army) (Major General Ralph C. Smith)

- Northern Attack Force (Task Force 52 – Makin)

- Southern Attack Force (Task Force 53 – Tarawa)

- Vice Admiral Harry W. Hill in battleship Maryland

- embarking 2nd Marine Division (Major General Julian C. Smith)

- Southern Attack Force (Task Force 53 – Tarawa)

Ground forces

![]() V Amphibious Corps[14]

V Amphibious Corps[14]

Major General Holland M. "Howlin' Mad" Smith, USMC

- Tarawa:

2nd Marine Division[13]

2nd Marine Division[13]- Major General Julian C. Smith

- 2nd Marine Regiment (Col. David M. Shoup)[lower-alpha 2]

- 6th Marine Regiment (Col. Maurice G. Holmes)

- 8th Marine Regiment (Col. Elmer E. Hall)

- 10th Marine Regiment (Artillery) (Col. Thomas E. Bourke)

- 18th Marine Regiment (Engineer) (Col. Cyril W. Martyr)

- Makin:

27th Infantry Division (Army)

27th Infantry Division (Army)- Major General Ralph C. Smith, USA

Japanese

Gilbert Islands defense forces[15]

Rear Adm. Keiji Shibasaki (KIA 20 Nov)

Approx. 5,000 total men under arms

- 3rd Special Base Force[lower-alpha 3]

- 7th Sasebo SNLF

- 111th Construction Unit

- 4th Fleet Construction Dept. (detachment)

Battle

20 November

The American invasion force to the Gilberts was the largest yet assembled for a single operation in the Pacific, consisting of 17 aircraft carriers (6 CVs, 5 CVLs, and 6 CVEs), 12 battleships, 8 heavy cruisers, 4 light cruisers, 66 destroyers, and 36 transport ships. On board the transports were the 2nd Marine Division and the Army's 27th Infantry Division, for a total of about 35,000 troops.

As the invasion flotilla hove to in the predawn hours, the island's four 8-inch guns opened fire. A gunnery duel developed as the main batteries on the battleships USS Colorado and USS Maryland commenced counter-battery fire. This proved effective, with several of the 16-inch shells finding their marks. One shell penetrated the ammunition storage for one of the guns, setting off a huge explosion as the ordnance went up in a massive fireball. Three of the four guns were knocked out in short order. One continued its intermittent, though inaccurate, fire through the second day. The damage to the big guns left the approach to the lagoon open.

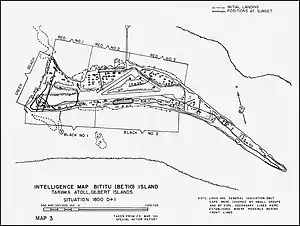

Following the gunnery duel and an air attack of the island at 06:10, the naval bombardment of the island began in earnest and was sustained for the next three hours. Two minesweepers, with two destroyers to provide covering fire, entered the lagoon in the pre-dawn hours and cleared the shallows of mines.[16] A guide light from one of the minesweepers then guided the landing craft into the lagoon, where they awaited the end of the bombardment. The plan was to land Marines on the north beaches, divided into three sections: Red Beach 1 on the far west of the island, Red Beach 2 in the center just west of the pier, and Red Beach 3 to the east of the pier.[17] Green Beach was a contingency landing beach on the western shoreline and was used for landings on 21 November. Black Beaches 1 and 2 made up the southern shore of the island and were not used. The airstrip, running roughly east–west, divided the island into north and south.

Marine Corps battle planners had expected the normal rising tide to provide a water depth of 5 feet (1.5 m) over the reef, allowing their 4 feet (1.2 m) draft Higgins boats room to spare. However, on this day and the next, the ocean experienced a neap tide and failed to rise. In the words of some observers, "the ocean just sat there", leaving a mean depth of 3 feet (0.91 m) over the reef. A New Zealand Army liaison officer, Major Frank Holland, had 15 years' experience on Tarawa and warned that there would be at most 3 feet depth. Shoup warned his Marines that there would be a 50–50 chance that they would need to wade ashore, but the attack was not delayed until more favorable spring tides.[18][19]

The supporting naval bombardment lifted, and the Marines started their attack from the lagoon at 09:00, thirty minutes later than expected, but found the tide had not risen enough to allow their shallow draft Higgins boats to clear the reef.[20] Only the tracked LVT "Alligators" were able to get across. With the pause in the naval bombardment, those Japanese who had survived the shelling were again able to man their firing pits. Japanese troops from the southern beaches were shifted up to the northern beaches. As the LVTs made their way over the reef and into the shallows, the number of Japanese troops in the firing pits slowly began to increase, and the volume of combined arms fire the LVTs faced gradually intensified. The LVTs had a myriad of holes punched through their non-armored hulls, and many were knocked out of the battle. Those LVTs that did make it in proved unable to clear the sea wall, leaving the men in the first assault waves pinned down against the log wall along the beach. Several LVTs went back out to the reef in an attempt to carry in the men who were stuck there, but most of these were too badly holed to remain seaworthy, leaving the Marines stuck on the reef some 500 yards (460 m) off shore. Half of the LVTs were knocked out of action by the end of the first day.

Shoup was the senior officer of the landed forces, and he assumed command of all landed Marines upon his arrival on shore. Although wounded by an exploding shell soon after landing at the pier, Shoup had the pier cleared of Japanese snipers and rallied the first wave of Marines who had become pinned down behind the limited protection of the sea wall. Over the next two days, working without rest and under constant withering enemy fire, he directed attacks against strongly defended Japanese positions, pushing forward despite daunting defensive obstructions and heavy fire. Throughout, Shoup was repeatedly exposed to Japanese small arms and artillery fire, inspiring the forces under his command. For his actions on Betio, he was awarded the Medal of Honor.[21]

Early attempts to land tanks for close support and to get past the sea wall failed when the LCM landing craft (LCM) carrying them hung up behind the reef. Some of these craft were hit out in the lagoon while they waited to move in to the beach and either sank outright or had to withdraw while taking on water. Two Stuart tanks were landed on the east end of the beach but were knocked out of action fairly quickly. The battalion commander of 3rd Battalion, 2nd Regiment found several LCMs near the reef and ordered them to land their Sherman tanks and head to Red Beach 2. The LCMs dropped ramps and the six tanks came down, climbed over the reef and dropped into the surf beyond. They were guided in to shore by Marines on foot, but several of these tanks fell into holes caused by the naval gunfire bombardment and sank.[22] The surviving Shermans on the western end of the island proved considerably more effective than the lighter Stuarts. They helped push the line in to about 300 yards (270 m) from shore. One became stuck in a tank trap, and another was knocked out by a magnetic mine. The remaining tank took a shell hit to its barrel and had its 75 mm gun disabled. It was used as a portable machine gun pillbox for the rest of the day. A third platoon was able to land all four of its tanks on Red 3 around noon and operated them successfully for much of the day, but by day's end only one tank was still in action.

By noon the Marines had successfully taken the beach as far as the first line of Japanese defenses. By 15:30 the line had moved inland in places but was still generally along the first line of defenses. The arrival of the tanks started the line moving on Red 3 and the end of Red 2 (the right flank, as viewed from the north), and by nightfall the line was about half-way across the island, only a short distance from the main runway.

Major Michael P. Ryan, a company commander, had gathered together remnants of his company with diverse disconnected Marines and sailors from other landing waves, as well as two Sherman tanks, and had diverted them onto a more lightly defended section of Green Beach. This impromptu unit was later referred to as "Ryan's Orphans". Ryan, who had been thought to be dead, arranged for naval gunfire and mounted an attack that cleared the island's western end.[12]

The communication lines that the Japanese installed on the island had been laid shallow and were destroyed in the naval bombardment, effectively preventing commander Keiji Shibazaki's direct control of his troops. In mid-afternoon, he and his staff abandoned the command post at the northeast end of the airfield to allow it to be used to shelter and care for the wounded, and he prepared to move to the south side of the island. He had ordered two of his Type 95 light tanks to act as a protective cover for the move, but a 5-inch naval artillery shell exploded in the midst of his headquarters personnel as they were assembled outside the central concrete command post, resulting in the death of the commander and most of his staff. This loss further complicated Japanese command problems.[23][24]

As night fell on the first day, the Japanese defenders kept up sporadic harassing fire but did not launch an attack on the Marines clinging to their beachhead and the territory won in the day's hard fighting. With Shibazaki killed and their communication lines torn up, each Japanese unit had been acting in isolation since the start of the naval bombardment. The Marines brought a battery of 75 mm Pack Howitzers ashore, unpacked them and set them up for action for the next day's fight, but most of the second wave was unable to land. They spent the night floating in the lagoon without food or water, trying to sleep in their Higgins boats.

During the night, some Japanese marines swam to some of the wrecked LVTs in the lagoon, and to the Saida Maru (斉田丸), a wrecked Japanese steamship lying west of the main pier. They waited for dawn, when they intended to fire on U.S. forces from behind. Lacking central direction, the Japanese were unable to coordinate for a counterattack against the toehold the Marines held on the island. The feared counterattack never came, and the Marines held their ground. By the end of the first day, of the 5,000 Marines put ashore, 1,500 were casualties, either dead or wounded.

21 November

With the Marines holding a thin line on the island, they were commanded to attack Red Beach 2 and 3 and push inward and divide the Japanese defenders into two sections, expanding the bulge near the airfield until it reached the southern shore. Those forces on Red 1 were directed to secure Green Beach for the landing of reinforcements. Green Beach made up the entire western end of the island.[25]

The effort to take Green Beach initially met with heavy resistance. Naval gunfire was called in to reduce the pill boxes and gun emplacements barring the way. Inching their way forward, artillery spotters were able to direct naval gunfire directly upon the machine gun posts and remaining strong points. With the major obstacles reduced, the Marines were able to take the positions in about an hour of combat with relatively few losses.[26]

Operations along Red 2 and Red 3 were considerably more difficult. During the night the defenders had set up several new machine gun posts between the closest approach of the forces from the two beaches, and fire from those machine gun nests cut off the Marines from each other for some time. By noon the Marines had brought up their own heavy machine guns, and the Japanese posts were put out of action. By the early afternoon they had crossed the airstrip and had occupied abandoned defensive works on the south side.[25]

Around 12:30 a message arrived that some of the defenders were making their way across the sandbars from the extreme eastern end of the islet to Bairiki, the next islet over.[25] Portions of the 6th Marine Regiment were ordered to land on Bairiki to seal off the retreat path. They formed up, including tanks and pack artillery, and were able to start their landings at 16:55. They received machine gun fire, so aircraft were sent in to try to locate the guns and suppress them. The force landed with no further fire, and it was later found that only a single pillbox with 12 machine guns had been set up by the forces that had been assumed to be escaping. They had a small tank of gasoline in their pillbox, and when it was hit with fire from the aircraft the entire force was burned.[21] Later, other units of the 6th Marine Regiment were landed unopposed on Green Beach, north (near Red Beach 1).[27]

By the end of the day, the entire western end of the island was in U.S. control, as well as a fairly continuous line between Red 2 and Red 3 around the airfield aprons. A separate group had moved across the airfield and set up a perimeter on the southern side, up against Black 2. The groups were not in contact with each other, with a gap of over 500 yards (460 m) between the forces at Red 1/Green and Red 2, and the lines on the northern side inland from Red 2/Red 3 were not continuous.[27]

22 November

The third day of battle consisted primarily of consolidating existing lines along Red 1 and 2, an eastward thrust from the wharf, and moving additional heavy equipment and tanks ashore onto Green Beach at 08:00.[28] During the morning the forces originally landed on Red 1 made some progress towards Red 2 but took casualties. Meanwhile, the 6th Marines which had landed on Green Beach to the south of Red 1 formed up while the remaining battalion of the 6th landed.

By the afternoon the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines (1/6) were sufficiently organized and equipped to take to the offensive. At 12:30 they pressed the Japanese forces across the southern coast of the island. By late afternoon they had reached the eastern end of the airfield and had formed a continuous line with the forces that landed on Red 3 two days earlier.[29] By the evening the remaining Japanese forces were either pushed back into the tiny amount of land to the east of the airstrip, or operating in several isolated pockets near Red 1/Red 2 and near the western edge of the airstrip.

That night the Japanese forces formed up for a counterattack, which started at about 19:30.[30] Small units were sent in to infiltrate the U.S. lines in preparation for a full-scale assault. The assembling forces were broken up by concentrated artillery fire, and the assault never took place.

23 November

A large banzai charge was made at 03:00 and met with some success, killing 45 Americans and wounding 128.[31] With support from the destroyers Schroeder and Sigsbee, the Marines killed 325 Japanese attackers.[31] At 04:00 the Japanese attacked Major Jones' 1st Battalion, 6th Marines in force. Roughly 300 Japanese troops launched a banzai charge into the lines of A and B Companies. Receiving support from 1st Battalion, 10th Marines' 75mm pack howitzers and the destroyers Schroeder and Sigsbee, the Marines were able to beat back the attack but only after calling artillery to within 75 meters of their own lines.[32] When the assault ended about an hour later there were 200 dead Japanese soldiers in the Marine front lines and another 125 beyond their lines.

At 07:00 Navy fighters and dive bombers started softening up the Japanese positions on the eastern tip of the island. After 30 minutes of air attack the pack howitzers of 1/10 opened up on the Japanese positions. Fifteen minutes later the Navy kicked off the last part of the bombardment with a further 15 minutes of shelling. At 08:00 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines (3/6) under the command of Lieutenant Colonel McLeod attacked, Jones' 1/6 having been pulled off the line after suffering 45 killed and 128 wounded in the previous night's fighting. Due to the narrowing nature of the island, I and L Companies of 3/6 formed the entire Marine front with K Company in reserve. The Marines advanced quickly against the few Japanese left alive on the eastern tip of Betio. They had two Sherman tanks named Colorado and China Gal, 5 light tanks in support and engineers in direct support.[33]

I and L Companies advanced 350 yards (320 m) before experiencing any serious resistance in the form of connected bunkers on I Company's front. McLeod ordered L Company to continue their advance, thereby bypassing the Japanese position. At this point L Company made up the entire front across the now 200 yards (180 m) wide island, while I Company reduced the Japanese strong point with the support of the tank Colorado and attached demolition/flame thrower teams provided by the engineers. As I Company closed in, the Japanese broke from cover and attempted to retreat down a narrow defile. Alerted to the attempted retreat, the commander of the Colorado tank fired in enfilade at the line of fleeing soldiers. The near total destruction of the Japanese soldiers' bodies made it impossible to know how many men were killed by this single shot, but it was estimated that 50 to 75 men perished. While L Company advanced down the eastern end of the island, Major Schoettel's 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines (3/2) and Major Hay's 1st Battalion, 8th Marines (1/8) were cleaning out the Japanese pocket that still existed between beaches Red 1 and Red 2. This pocket had been resisting the advance of the Marines landing on Red 1 and Red 2 since D-day, and they had not yet been able to move against it.[34]

1/8 advanced on the pocket from the east (Red 2) while 3/2 advanced from the west (Red 1). Major Hewitt Adams led an infantry platoon supported by two pack howitzers from the lagoon into the Japanese positions to complete the encirclement. By noon the pocket had been reduced. On the eastern end of the island L Company continued to advance, bypassing pockets of resistance and leaving them to be cleared out by tanks, engineers and air support. By 13:00 they had reached the eastern tip of Betio. 3/6 killed roughly 475 Japanese soldiers on the morning of 23 November while losing 9 killed and 25 wounded. Back at the Red 1/Red 2 pocket there was no accurate count of Japanese dead. There were an estimated 1,000 Japanese alive and fighting on the night of 22 November, 500 on the morning of 23 November and only 50–100 left when the island was declared secure at 13:30 on 23 November.[35]

Aftermath

For the next several days the 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines moved up through the remaining islands in the atoll and cleared the area of Japanese, completing this on 28 November. The 2nd Marine Division started shipping out soon after and were completely withdrawn by early 1944.

Of the 3,636 Japanese in the garrison, only one officer and sixteen enlisted men surrendered. Of the 1,200 Korean laborers brought to Tarawa to construct the defenses, only 129 survived. All told, 4,690 of the island's defenders were killed.[36] The 2nd Marine Division suffered 894 killed in action, 48 officers and 846 enlisted men, while an additional 84 of the wounded survivors later succumbed to what proved to be fatal wounds. Of these, 8 were officers and 76 were enlisted men. A further 2,188 men were wounded in the battle, 102 officers and 2,086 men. Of the roughly 12,000 2nd Marine Division Marines on Tarawa, 3,166 officers and men became casualties.[37] Nearly all of these casualties were suffered in the 76 hours between the landing at 09:10 on 20 November and the island of Betio being declared secure at 13:30 23 November.[38]

The heavy casualties suffered by the United States at Tarawa[39] sparked public protest, where headline reports of the high losses could not be understood for such a small and seemingly unimportant island.[5][40] The public reaction was aggravated by the unguardedly frank comments of some of the Marine Corps command. General Holland Smith, commander of the V Amphibious Corps who had toured the beaches after the battle, likened the losses to Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg. Admiral Chester Nimitz was inundated with angry letters from families of men killed on the island.

Back in Washington, newly appointed Marine Corps Commandant Alexander Vandegrift, the widely respected and highly decorated veteran of Guadalcanal, reassured Congress, pointing out that "Tarawa was an assault from beginning to end". A New York Times editorial on 27 December 1943 praised the Marines for overcoming Tarawa's rugged defenses and fanatical garrison and warned that future assaults in the Marshalls might well result in heavier losses. "We must steel ourselves now to pay that price."[41]

Writing after the war, Smith, who in his biography was highly critical of the Navy, commented:

Was Tarawa worth it? My answer is unqualified: No. From the very beginning the decision of the Joint Chiefs to seize Tarawa was a mistake and from their initial mistake grew the terrible drama of errors, errors of omission rather than commission, resulting in these needless casualties.[42]

Some commanders involved, including Nimitz, Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, Lieutenant General Julian C. Smith and Lieutenant Colonel David M. Shoup, disagreed with General Smith. Said Nimitz:

The capture of Tarawa knocked down the front door to the Japanese defenses in the Central Pacific.[41]

Nimitz launched the Marshalls campaign ten weeks after the seizure of Tarawa. Aircraft flown from airfields at Betio and Abemama proved highly valuable.

All told, nearly 6,400 Japanese, Koreans and Americans died on the tiny island in 76 hours of fighting.[5] In the aftermath of the battle, American casualties lined the beach and floated in the surf. Staff Sergeant Norman Hatch and other Marine cameramen were present obtaining footage that would later be used in a documentary.[43] With the Marines at Tarawa contained scenes of American dead so disturbing that the decision of whether to release it to the public was deferred to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who approved it.

Following the battle, the 2nd Marine Division was shipped to Hawaii, leaving the 2nd Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment behind to clear the battlefield of ordnance, provide security for the Seabees rebuilding the airstrip and aid in the burial detail. The 2nd Marine Division remained in Hawaii for six months, refitting and training, until called upon for its next major amphibious landing, the Battle of Saipan in the Marianas in June 1944.

Lessons

The greater significance of the action on Tarawa to the success in the Marshalls proved to be the lessons learned from the battle. It was the first time in the war that a United States amphibious landing was opposed by well entrenched, determined defenders. Previous landings, such as the landing at Guadalcanal, had been unexpected and met with little or no initial resistance. At the time, Tarawa was the most heavily defended atoll invaded by Allied forces in the Pacific.[44]

The casualties by the United States at Tarawa resulted from several contributing factors, among which were the miscalculation of the tide and the height of the obstructing coral reefs, the operational shortcomings of the landing craft available, the inability of the naval bombardment to weaken the defenses of a well entrenched enemy, and the difficulties of coordinating and communicating between the different military branches involved.

Navy battleships and cruisers had fired some three thousand shells into Tarawa in the three hours before the landings. "This was by far the heaviest bombardment of an invasion beach ever delivered up to that time. Yet it proved inadequate. ... The high explosive shells employed by the bombarding ships usually went off before penetrating the Japanese defensive works (thus) doing little real damage." For the subsequent Marshalls campaign, the naval bombardments took a month and included the use of armor-piercing shells, while the landing craft also had armor.[45]

The failures of the Tarawa landing were a major factor in the founding of the Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT) the precursor of the current U.S. Navy SEALS – after Tarawa "the need for the UDT in the South Pacific became glaringly clear". The "landing on Tarawa Atoll emphasized the need for hydrographic reconnaissance and underwater demolition of obstacles prior to any amphibious landing". "After the Tarawa landing, Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner directed the formation of nine Underwater Demolition Teams. Thirty officers and 150 enlisted men were moved to the Waimānalo Amphibious Training Base to form the nucleus of a demolition training program. This group became UDT ONE and UDT TWO." [46]

Legacy

War Correspondent Robert Sherrod wrote:

Last week some 2,000 or 3,000 United States Marines, most of them now dead or wounded, gave the nation a name to stand beside those of Concord Bridge, the Bonhomme Richard, the Alamo, Little Bighorn, and Belleau Wood. The name was Tarawa.

— Robert Sherrod, "Report On Tarawa: Marines' Show" Time magazine war correspondent, 6 December 1943[47]

Over one hundred of the Americans killed were never repatriated.[48] In November 2013, the remains of one American and four Japanese were recovered from "what was considered a pristine site preserving actual battlefield conditions and all remains found as they fell."[49] The remains of 36 Marines, including 1st Lieutenant Alexander Bonnyman Jr., were interred in a battlefield cemetery whose location was lost by the end of the war. The cemetery was located in March 2015.[50] On 26 July 2015, the bodies were repatriated to the United States, arriving at Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam, Hawaii.[51] In March, 2019 a mass grave of Marines, reportedly from the 6th Marine Regiment, was discovered on Tarawa. The remains of 22 Marines recovered from the mass grave arrived at the Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii on 17 July 2019.[52]

Gallery

Aerial view of Betio Island looking east, before invasion of the island by U.S. Marines, 18 September 1943. The image was taken by an aircraft from Composite Squadron 24.

Aerial view of Betio Island looking east, before invasion of the island by U.S. Marines, 18 September 1943. The image was taken by an aircraft from Composite Squadron 24. Japanese 14-cm gun emplacement on Tarawa 1943; note the holes in the gun shield

Japanese 14-cm gun emplacement on Tarawa 1943; note the holes in the gun shield Destruction of one of the four Japanese 8-inch Vickers guns on Betio was caused by naval gunfire and air strikes.

Destruction of one of the four Japanese 8-inch Vickers guns on Betio was caused by naval gunfire and air strikes. Japanese 8-inch gun emplacement on Tarawa (1996)

Japanese 8-inch gun emplacement on Tarawa (1996) "Tarawa, South Pacific, 1943" painting by Sergeant Tom Lovell, USMC

"Tarawa, South Pacific, 1943" painting by Sergeant Tom Lovell, USMC.png.webp) Marines crossing Japanese-laid barbed wire in Betio Island (colorized)

Marines crossing Japanese-laid barbed wire in Betio Island (colorized) An M4 Sherman rests in the lagoon.

An M4 Sherman rests in the lagoon. Japanese defenders knocked out this LVT on Beach RED 1.

Japanese defenders knocked out this LVT on Beach RED 1. View of the beach of Betio Island, Tarawa

View of the beach of Betio Island, Tarawa Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of dead Japanese soldiers after the battle

Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of dead Japanese soldiers after the battle Two Japanese Imperial Marines who shot themselves rather than surrender to U.S. Marines on Tarawa

Two Japanese Imperial Marines who shot themselves rather than surrender to U.S. Marines on Tarawa Aerial view of Betio Island, 24 November 1943, looking north toward "The Pocket", the last place of Japanese resistance. An emplacement just onshore with two 12.7 mm anti-aircraft guns is visible near the left edge of the photograph.

Aerial view of Betio Island, 24 November 1943, looking north toward "The Pocket", the last place of Japanese resistance. An emplacement just onshore with two 12.7 mm anti-aircraft guns is visible near the left edge of the photograph. The largest of 37 cemeteries on Tarawa

The largest of 37 cemeteries on Tarawa

See also

- USS Tarawa, for U.S. Navy ships named for the Battle of Tarawa

Footnotes

- At 09:10 on 7 August, Vandegrift and 11,000 U.S. marines came ashore on Guadalcanal between Koli Point and Lunga Point. Advancing towards Lunga Point, they encountered no resistance except for "tangled" rain forest, and they halted for the night about 1,000 yards (910 m) from the Lunga Point airfield.

- Also commander of landed troops; awarded the Medal of Honor for his extraordinary leadership during the chaos of the initial assault.

- Formerly 6th Yokosuka SNLF

Notes

- "Battle of Tarawa". History.com. 16 February 2016.

- Wright 2004, p. 93.

- Morison, Samuel (1952). Aleutians Gilberts And Marshalls June 1942 April 1944. Oxford University. p. 158.

- "Battle of Tarawa". World War 2 Facts. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- Alexander 1993, p. 50.

- Wheeler 1983, p. 170.

- Morison 1951, p. 15.

- Wheeler 1983, p. 167.

- Wright 2004, p. 18.

- Intelligence Bulletin (March 1944). "Defense of Betio Island".

- Wright 2004, p. 10.

- Alexander 1993, p. 14.

- Morison 1951, pp. 86–87.

- Morison 1951, pp. 89–90.

- Wright 2004, p. 92.

- Rice Strategic Battles of the Pacific p. 53

- Wheeler 1983, p. 174.

- 'Major Francs Holland' in McGibbon (ed) The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Military History p. 220

- "Across the Reef: The Marine Assault of Tarawa".

- Russ Line of Departure: Tarawa p. 102

- Alexander 1993, p. 33.

- Wheeler 1983, p. 180.

- Masanori Ito; Sadatoshi Tomiaka; Masazumi Inada (1970). Real Accounts of the Pacific War, vol. III. Chuo Koron Sha.

- "Japanese Armor". Tarawa on the Web. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- Alexander 1993, p. 28.

- Alexander 1993, p. 31.

- Alexander 1993, p. 34.

- Wright 2004, p. 61.

- Wright 2004, p. 65.

- Wright 2004, p. 68.

- Wright 2004, p. 69.

- Johnston 1948, p. 146.

- Johnston 1948, p. 147.

- Johnston 1948, p. 149.

- Johnston 1948, p. 150.

- "Japanese Casualties from The Battle for Tarawa, USMC Historical Monograph". ibiblio at University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- Johnston 1948, pp. 164, 305.

- Johnston 1948, p. 111.

- "Tarawa on the Web". Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- "Marine Casualties from The Battle for Tarawa, USMC Historical Monograph". ibiblio at University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- Alexander 1993, p. 51.

- Smith Coral and Brass pp. 111–112

- "WWII Combat Cameraman: 'The Public Had To Know'". NPR.org. 22 March 2010. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- "Chronology of Events at Tarawa from The Battle for Tarawa, USMC Historical Monograph". ibiblio at University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- Spector, Ronald, Eagle Against the Sun, p. 262

- "Navy SEAL History – The South Pacific – Growth of UDT". navyseals.com. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- "Report On Tarawa: Marines' Show". Time. 6 December 1943.

- "Return to Tarawa". The Tokyo Reporter. 14 September 2009. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- Tim Preston (26 July 2014). "Marine's death could have deeper meaning". The Independent. Ashland, KY. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

This little 17-year-old guy from Rush jumped in that pit ... According to all the official records, he should've never got over that wall or been where he was.

- Miller, Michael E. (2 July 2015). "'Golden' ending: How one man discovered his war hero grandfather's long lost grave". The Washington Post. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Stars and Stripes, "70 years after a 'most significant' battle, 36 Marines honored in Hawaii", p. 3, 30 July 2015

- Stars and Stripes – Wyatt Olson article

References

- Alexander, Joseph H. (1993). Across the Reef: The Marine assault of Tarawa (PDF). History and Museums Division United States Marine Corps. ISBN 978-1481999366.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Clark, George B. (2006). The Six Marine Divisions in the Pacific: Every Campaign of World War II. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-2769-7.

- Johnston, Richard (1948), Follow Me!: The Story of The Second Marine Division in World War II, Canada: Random House of Canada Ltd

- Masanori Ito, Sadatoshi Tomiaka and Masazumi Inada Real Accounts of the Pacific War, vol. III Chuo Koron Sha1970.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1951). Aleutians, Gilberts and Marshalls, June 1942 – April 1944. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. VII. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-31658-307-7.

- Potter, E.B. and Nimitz, Chester (1960) Sea Power: A Naval History Prentice Hall ISBN 978-0-87021-607-7

- Rice, Earle (2000) Strategic Battles of the Pacific Lucent Books ISBN 1-56006-537-0

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2004). US Marine Corps Pacific Theater of Operationss 1944–45. Osprey Press. ISBN 1841766593.

- Russ, Martin (1975) Line of Departure: Tarawa Doubleday ISBN 978-0-385-09669-0

- Smith, General Holland M., USMC (Ret.) (1949) Coral and Brass New York, New York: Scribners ISBN 978-0-553-26537-8

- Wheeler, Richard (1983), A Special Valor: The U.S. Marines and the Pacific War, New York: Harper & Row

- Wright, Derrick (2004), Tarawa 1943: The Turning of the Tide, Oxford: Osprey, ISBN 1841761028

Further reading

- Alexander, Joseph H. (1995). Utmost Savagery: The Three Days of Tarawa. Naval Institute Press.

- Graham, Michael B (1998). Mantle of Heroism: Tarawa and the Struggle for the Gilberts, November 1943. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-652-8.

- Gregg, Howard F. (1984). Tarawa. Sein and Day. ISBN 0-8128-2906-9.

- Hammel, Eric; John E. Lane (1998). Bloody Tarawa. Zenith Press. ISBN 0-7603-2402-6.

- Rogers, Daniel (2022). The Battle of Tarawa. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1591147039.

- Spiva, Dave (December 2018). "'Bloody, Bloody' Tarawa". VFW Magazine. Vol. 106, no. 3. Kansas City, Mo.: Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States. pp. 36–38. ISSN 0161-8598.

Nov. 20 marks 75 years since the American assault against Japanese forces on Tarawa in World War II. The victory on the Central Pacific island came at a high cost for the Marine Corps, but the lessons learned proved invaluable in later amphibious assaults.

- Wukovitz, John (2007). One Square Mile of Hell: The Battle for Tarawa. NAL Trade. ISBN 978-0-451-22138-4.

External links

- Tarawa on The Web Archived 1 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- The short film With the Marines at Tarawa (1944) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Animated History of The Battle of Tarawa

- "Operation Galvanic (1): The Battle for Tarawa November 1943". History of War.

- Defense of Betio Island, Intelligence Bulletin, U.S. War Department, March 1944.

- The Assault of the Second Marine Division on Betio Island, Tarawa Atoll, 20–23 November 1943 Archived 1 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Eyewitnesstohistory.com – The Bloody Battle of Tarawa

- Marines in World War II Historical Monograph: The Battle for Tarawa

- Slugging It Out In Tarawa Lagoon

- Heinl, Robert D., and John A. Crown (1954). "The Marshalls: Increasing the Tempo". USMC Historical Monograph. Historical Division, Division of Public Information, Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps. Archived from the original on 16 November 2006. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific), Naval Analysis Division (1946). "Chapter IX: Central Pacific Operations From 1 June 1943 to 1 March 1944, Including the Gilbert-Marshall Islands Campaign". The Campaigns of the Pacific War. United States Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2007.

- George C., Dyer, Vice Admiral, USN (Ret) (1956). The Amphibians Came to Conquer. LCCN 71-603853. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Tarawa" cat survivor adopted by U.S. Coast Guard

- Oral history interview with John E. Pease, a U.S. Marine Veteran who took part in the Battle of Tarawa Archived 12 December 2012 at archive.today from the Veterans History Project at Central Connecticut State University

- National Archives historical footage of the battle for Tarawa